Web Fuzzing

Cheat Sheet

What is Web Fuzzing?

Web fuzzing is a technique used to discover vulnerabilities, hidden resources, and security issues in web applications by automatically injecting a large set of input data into the application and analyzing its response. The goal is to identify unexpected behaviors or errors that could indicate potential security weaknesses or misconfigurations.

Fuzzing is commonly employed in security testing to find:

- Hidden directories and files

- Insecure APIs and endpoints

- SQL injection points

- Cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerabilities

- Command injection flaws

Comparison: Brute-Forcing vs. Fuzzing

Criteria |

Brute-Forcing |

Fuzzing |

|---|---|---|

Definition |

Systematically trying all possible combinations of input data to guess a specific value. | Injecting unexpected or random data into an application to find vulnerabilities and hidden resources. |

Purpose |

Crack passwords, keys, or other access credentials. | Discover application vulnerabilities, hidden files, directories, and input validation issues. |

Methodology |

Exhaustive search over all possible input combinations. | Dynamic input injection to provoke unexpected application responses. |

Focus |

Specific input or data, such as passwords or API keys. | General application behavior under various input conditions. |

Efficiency |

Time-consuming due to exhaustive nature; less efficient for large input spaces. | More efficient in identifying unexpected behaviors and vulnerabilities with varied input. |

Tools Used |

Password crackers, key recovery tools. | Web fuzzers, vulnerability scanners. |

Output |

Successful match of the correct input value. | Discovery of vulnerabilities, misconfigurations, and hidden resources. |

Miscellaneous Commands

Below are some useful commands that can aid in various tasks related to web fuzzing and testing.

Command |

Description |

|---|---|

sudo sh -c 'echo "SERVER_IP academy.htb" >> /etc/hosts' |

Add a DNS entry for a specific IP address to the /etc/hosts file. This helps resolve domain names locally. |

for i in $(seq 1 1000); do echo $i >> ids.txt; done |

Create a sequence wordlist from 1 to 1000. Useful for brute-forcing numerical IDs or similar patterns. |

curl http://admin.academy.htb:PORT/admin/admin.php -X POST -d 'id=key' -H 'Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded' |

Use curl to send a POST request with specific data and headers, simulating form submissions or API calls. |

Commonly Used SecLists Wordlists

SecLists is a collection of multiple types of wordlists used by security researchers and penetration testers. Below is a table of some commonly used wordlists from SecLists, which can be incredibly valuable during web fuzzing.

Wordlist |

Description |

|---|---|

/usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt |

General-Purpose Wordlist: Contains a broad range of common directory and file names on web servers. It's an excellent starting point for fuzzing and often yields valuable results. |

/usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/directory-list-2.3-medium.txt |

Directory-Focused Wordlist: A more extensive wordlist specifically focused on directory names. It's a good choice when you need a deeper dive into potential directories. |

/usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/raft-large-directories.txt |

Large Directory Wordlist: Boasts a massive collection of directory names compiled from various sources. It's a valuable resource for thorough fuzzing campaigns. |

/usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/big.txt |

Comprehensive Wordlist: A massive wordlist containing both directory and file names. Useful when you want to cast a wide net and explore all possibilities. |

Tips for Using Wordlists Effectively

Tip |

Explanation |

|---|---|

Choose the Right Wordlist |

Select wordlists relevant to the target environment and technology stack for better results. |

Combine Wordlists |

Use multiple wordlists together to increase the breadth of your fuzzing efforts. |

Customize Wordlists |

Modify existing wordlists or create your own based on specific knowledge about the target. |

Monitor Performance |

Large wordlists can be resource-intensive; monitor performance and adjust as needed. |

Leverage Community Resources |

Utilize community-maintained wordlists for the latest and most effective fuzzing strategies. |

Tools for Web Fuzzing

ffuf (Fuzz Faster U Fool)

ffuf is a fast web fuzzer written in Go that allows you to discover directories and files on web servers.

Command |

Description |

|---|---|

ffuf -u http://example.com/FUZZ |

Basic fuzzing of a URL path. |

ffuf -u http://example.com/FUZZ -w wordlist.txt |

Fuzz with a specific wordlist. |

ffuf -u http://example.com/FUZZ -w wordlist.txt -ic |

Fuzz with a specific wordlist, automatically ignoring any comments in the wordlist. |

ffuf -u http://example.com/FUZZ -w wordlist.txt -c |

Colorize the output for better readability. |

ffuf -u http://example.com/FUZZ -w wordlist.txt -mc 200 |

Filter results by status code (e.g., 200). |

ffuf -u http://example.com/FUZZ -w wordlist.txt -mr "Welcome" |

Filter results by matching a regex pattern. |

ffuf -u http://example.com/FUZZ -w wordlist.txt -e .php,.html |

Add extensions to each wordlist entry. |

ffuf -u http://example.com/FUZZ -w wordlist.txt -t 50 |

Set the number of threads (e.g., 50) for faster fuzzing. |

ffuf -u http://example.com/FUZZ -w wordlist.txt -x http://127.0.0.1:8080 |

Use a proxy for requests. |

gobuster

gobuster is a tool used to brute-force URIs (directories and files) in web sites and DNS subdomains.

Command |

Description |

|---|---|

gobuster dir -u http://example.com -w wordlist.txt |

Directory fuzzing using a wordlist. |

gobuster dir -u http://example.com -w wordlist.txt -x .php,.html |

Fuzz with specific extensions. |

gobuster dir -u http://example.com -w wordlist.txt -s 200 |

Filter results by status code (e.g., 200). |

gobuster dir -u http://example.com -w wordlist.txt -t 50 |

Set the number of concurrent threads (e.g., 50). |

gobuster dir -u http://example.com -w wordlist.txt -o results.txt |

Output results to a file. |

gobuster dns -d example.com -w subdomains.txt |

Fuzz DNS subdomains using a wordlist. |

gobuster dns -d example.com -w subdomains.txt -i |

Show IP addresses of discovered subdomains. |

gobuster dns -d example.com -w subdomains.txt -z |

Silent mode; suppress output except for results. |

wneum (Wfuzz Fork)

wneum is a fork of wfuzz, a versatile web application fuzzer for testing web security.

Command |

Description |

|---|---|

wneum -c -z file,wordlist.txt --hc 404 http://example.com/FUZZ |

Basic fuzzing excluding 404 responses. |

wneum -c -z file,wordlist.txt -d 'username=FUZZ&password=secret' |

Fuzz POST data in a form. |

wneum -c -z file,wordlist.txt -b 'session=12345' |

Use a specific cookie for requests. |

wneum -c -z file,wordlist.txt -H 'User-Agent: Wneum' |

Add a custom header to requests. |

wneum -c -z file,wordlist.txt -t 50 |

Set the number of threads (e.g., 50) for faster fuzzing. |

wneum -c -z file,wordlist.txt -u http://example.com/FUZZ -X PUT |

Fuzz using a specific HTTP method (e.g., PUT). |

wneum -c -z file,wordlist.txt --hl 50 |

Filter responses by content length (e.g., 50 bytes). |

feroxbuster

feroxbuster is a tool designed for recursive content discovery and web fuzzing.

Command |

Description |

|---|---|

feroxbuster -u http://example.com -w wordlist.txt |

Basic URL fuzzing with a wordlist. |

feroxbuster -u http://example.com -w wordlist.txt -e |

Include specified file extensions in fuzzing. |

feroxbuster -u http://example.com -w wordlist.txt -x 404 |

Exclude responses with status code 404. |

feroxbuster -u http://example.com -w wordlist.txt -t 50 |

Set the number of concurrent threads (e.g., 50). |

feroxbuster -u http://example.com -w wordlist.txt --depth 3 |

Set maximum recursion depth (e.g., 3 levels deep). |

feroxbuster -u http://example.com -w wordlist.txt -o results.txt |

Save output to a file. |

feroxbuster -u http://example.com -w wordlist.txt --no-recursion |

Disable recursion into discovered directories. |

feroxbuster -u http://example.com -w wordlist.txt --url-redirect |

Follow redirects automatically. |

Tips for Effective Web Fuzzing

Tip |

Explanation |

|---|---|

Use Comprehensive Wordlists |

The quality of your wordlist can significantly impact results; choose or create wordlists relevant to the target. |

Filter Unwanted Responses |

Use status codes or response size filtering to focus on meaningful results and reduce noise. |

Adjust Thread Count |

Increase thread count for faster fuzzing, but be mindful of server capabilities to avoid overloading. |

Monitor Server Responses |

Pay attention to anomalies or unexpected behavior in server responses, indicating potential vulnerabilities. |

Fuzz with Various HTTP Methods |

Test different HTTP methods (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE) to uncover potential vulnerabilities in all endpoints. |

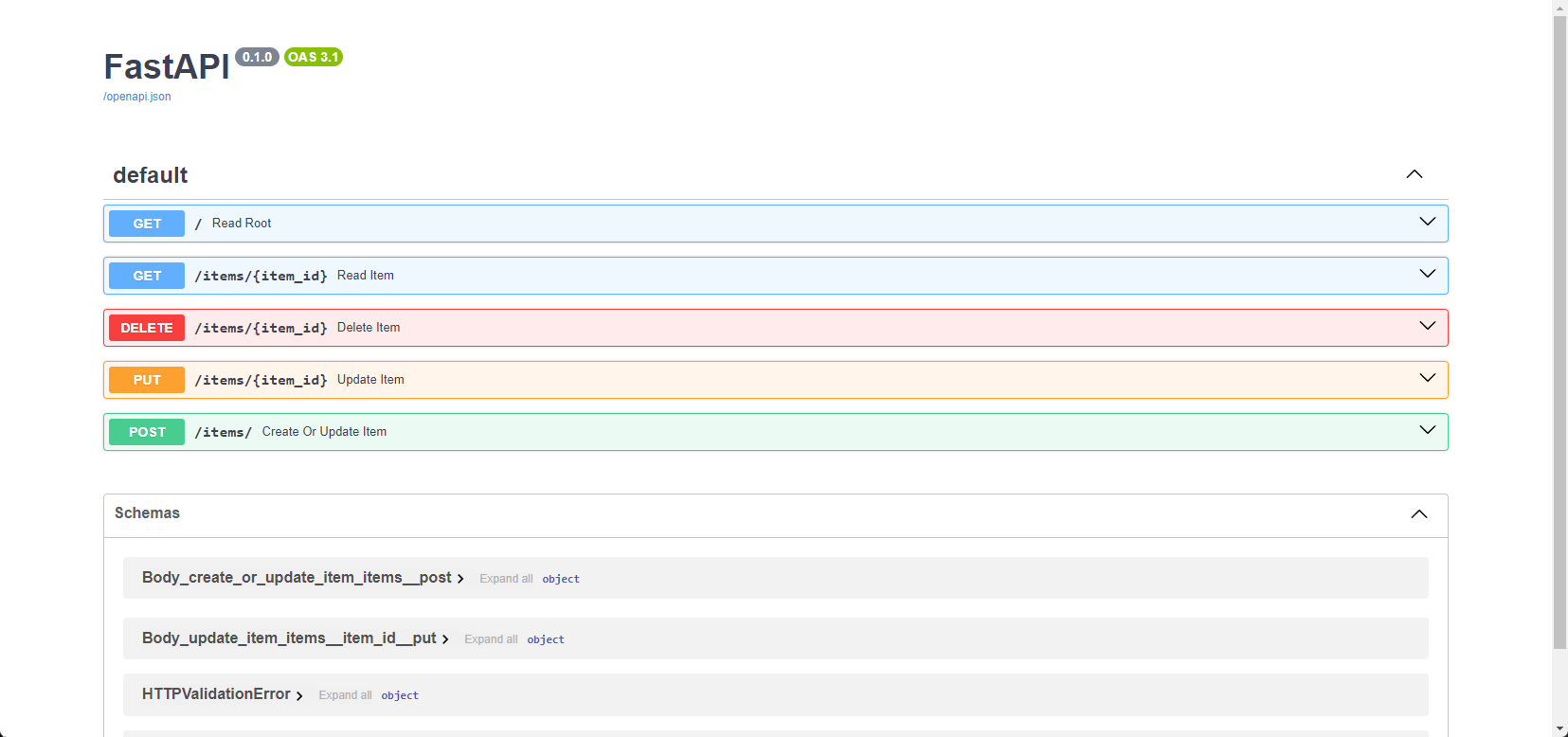

Web APIs: REST, SOAP, and GraphQL

What is a Web API?

A Web API (Application Programming Interface) is a set of rules and protocols for building and interacting with software applications. APIs allow different applications to communicate with each other over the internet, enabling the integration of various services and data exchange.

Web APIs can be categorized into three main types:

REST (Representational State Transfer)SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol)GraphQL

Each type has its own unique characteristics, advantages, and use cases.

REST (Representational State Transfer)

REST is an architectural style that uses standard HTTP methods to access and manipulate resources on a server. It is known for its simplicity, scalability, and statelessness.

Feature |

Description |

|---|---|

Protocol |

Uses HTTP/HTTPS. |

Data Format |

Typically JSON, but can also use XML, HTML, or plain text. |

Stateless |

Each request from a client to a server must contain all the information needed. |

CRUD Operations |

Uses HTTP methods: GET, POST, PUT, DELETE. |

Scalability |

Highly scalable due to its stateless nature. |

Caching |

Supports caching mechanisms to improve performance. |

URL Structure |

Uses endpoints that represent resources, e.g., /api/users/{id}. |

Advantages |

Simplicity, flexibility, scalability. |

Disadvantages |

Can lead to over-fetching or under-fetching data. |

REST Fuzzing Tips:

Tip |

Explanation |

|---|---|

Test All HTTP Methods |

Ensure all CRUD operations are tested, as vulnerabilities might exist in any of them. |

Validate Input Fields |

Fuzz input fields with unexpected data types and formats to uncover validation issues. |

Examine Error Messages |

Analyze error messages for information disclosure or unintended behavior. |

Test Authentication Mechanisms |

Check for improper authentication and authorization controls. |

Explore API Rate Limits |

Test rate limits and throttling controls to ensure the API handles requests properly. |

Use Comprehensive Payloads |

Leverage a variety of payloads (SQLi, XSS) to test for potential security flaws. |

Check Resource Representation |

Test different resource representations (JSON, XML) for consistency and security flaws. |

SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol)

SOAP is a protocol for exchanging structured information in web services. It uses XML as its message format and can operate over various protocols like HTTP, SMTP, or TCP.

Feature |

Description |

|---|---|

Protocol |

Protocol-independent but often used with HTTP/HTTPS. |

Data Format |

Exclusively XML. |

Stateful/Stateless |

Can be either stateful or stateless. |

WS-Security |

Built-in security features for message integrity and confidentiality. |

Error Handling |

Uses specific error codes and messages. |

Complexity |

More complex due to extensive standards and specifications. |

Extensibility |

Highly extensible via WS-* standards. |

Advantages |

Strong security, reliability, and extensibility. |

Disadvantages |

More complex and less flexible compared to REST. |

SOAP Fuzzing Tips:

Tip |

Explanation |

|---|---|

Analyze WSDL Files |

Use WSDL (Web Services Description Language) files to understand the service's operations and inputs. |

Validate XML Schema |

Test XML inputs against the schema to identify validation flaws. |

Check for XML Injection |

Fuzz XML data to test for injection vulnerabilities. |

Test SOAP Headers |

Fuzz SOAP headers to find potential security issues or misconfigurations. |

Evaluate WS-Security Implementations |

Ensure security implementations are robust and correctly configured. |

Test Transport Security |

Verify that transport-level security (e.g., HTTPS) is enforced and properly implemented. |

Examine SOAP Faults |

Analyze SOAP fault messages for potential information leakage. |

GraphQL

GraphQL is a query language and runtime for APIs that allows clients to request specific data and define the structure of the response.

Feature |

Description |

|---|---|

Protocol |

Uses HTTP/HTTPS, typically over POST requests. |

Data Format |

JSON-based queries and responses. |

Stateful/Stateless |

Stateless architecture. |

Query Flexibility |

Clients can request exactly what they need, minimizing over-fetching and under-fetching. |

Single Endpoint |

Typically uses a single endpoint for all operations. |

Introspection |

Allows clients to query the API schema for available operations and data types. |

Advantages |

Efficiency, flexibility, and powerful developer tooling. |

Disadvantages |

Potential for complex queries leading to performance issues if not properly managed. |

GraphQL Fuzzing Tips:

Tip |

Explanation |

|---|---|

Test Query Depth and Complexity |

Evaluate the server's handling of deeply nested or complex queries to avoid performance bottlenecks. |

Validate Input Types and Arguments |

Fuzz input arguments with unexpected values and data types to uncover validation flaws. |

Examine Query Aliasing and Batching |

Test the server's response to aliased queries and batching for potential information leakage. |

Check for Introspection Misuse |

Ensure introspection is not exposing sensitive information or internal schema details. |

Assess Authorization Controls |

Verify that access controls are properly enforced for different queries and operations. |

Evaluate Rate Limiting |

Test rate limits to ensure the API can handle excessive or malicious requests appropriately. |

Fuzz Mutations |

Mutations can alter data; test for security issues and improper input validation. |

Introduction

Web fuzzing is a critical technique in web application security to identify vulnerabilities by testing various inputs. It involves automated testing of web applications by providing unexpected or random data to detect potential flaws that attackers could exploit.

In the world of web application security, the terms "fuzzing" and "brute-forcing" are often used interchangeably, and for beginners, it's perfectly fine to consider them as similar techniques. However, there are some subtle distinctions between the two:

Fuzzing vs. Brute-forcing

- Fuzzing casts a wider net. It involves feeding the web application with unexpected inputs, including malformed data, invalid characters, and nonsensical combinations. The goal is to see how the application reacts to these strange inputs and uncover potential vulnerabilities in handling unexpected data. Fuzzing tools often leverage wordlists containing common patterns, mutations of existing parameters, or even random character sequences to generate a diverse set of payloads.

- Brute-forcing, on the other hand, is a more targeted approach. It focuses on systematically trying out many possibilities for a specific value, such as a password or an ID number. Brute-forcing tools typically rely on predefined lists or dictionaries (like password dictionaries) to guess the correct value through trial and error.

Here's an analogy to illustrate the difference: Imagine you're trying to open a locked door. Fuzzing would be like throwing everything you can find at the door - keys, screwdrivers, even a rubber duck - to see if anything unlocks it. Brute-forcing would be like trying every combination on a key ring until you find the one that opens the door.

Why Fuzz Web Applications?

Web applications have become the backbone of modern businesses and communication, handling vast amounts of sensitive data and enabling critical online interactions. However, their complexity and interconnectedness also make them prime targets for cyberattacks. Manual testing, while essential, can only go so far in identifying vulnerabilities. Here's where web fuzzing shines:

Uncovering Hidden Vulnerabilities: Fuzzing can uncover vulnerabilities that traditional security testing methods might miss. By bombarding a web application with unexpected and invalid inputs, fuzzing can trigger unexpected behaviors that reveal hidden flaws in the code.Automating Security Testing: Fuzzing automates generating and sending test inputs, saving valuable time and resources. This allows security teams to focus on analyzing results and addressing the vulnerabilities found.Simulating Real-World Attacks: Fuzzers can mimic attackers' techniques, helping you identify weaknesses before malicious actors exploit them. This proactive approach can significantly reduce the risk of a successful attack.Strengthening Input Validation: Fuzzing helps identify weaknesses in input validation mechanisms, which are crucial for preventing common vulnerabilities likeSQL injectionandcross-site scripting(XSS).Improving Code Quality: Fuzzing improves overall code quality by uncovering bugs and errors. Developers can use the feedback from fuzzing to write more robust and secure code.Continuous Security: Fuzzing can be integrated into thesoftware development lifecycle(SDLC) as part ofcontinuous integration and continuous deployment(CI/CD) pipelines, ensuring that security testing is performed regularly and vulnerabilities are caught early in the development process.

In a nutshell, web fuzzing is an indispensable tool in the arsenal of any security professional. By proactively identifying and addressing vulnerabilities through fuzzing, you can significantly enhance the security of your web applications and protect them from potential threats.

Essential Concepts

Before we dive into the practical aspects of web fuzzing, it's important to understand some key concepts:

| Concept | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

Wordlist |

A dictionary or list of words, phrases, file names, directory names, or parameter values used as input during fuzzing. | Generic: |

Payload |

The actual data sent to the web application during fuzzing. Can be a simple string, numerical value, or complex data structure. | ' OR 1=1 -- (for SQL injection) |

Response Analysis |

Examining the web application's responses (e.g., response codes, error messages) to the fuzzer's payloads to identify anomalies that might indicate vulnerabilities. | Normal: 200 OK |

Fuzzer |

A software tool that automates generating and sending payloads to a web application and analyzing the responses. | ffuf, wfuzz, Burp Suite Intruder |

False Positive |

A result that is incorrectly identified as a vulnerability by the fuzzer. | A 404 Not Found error for a non-existent directory. |

False Negative |

A vulnerability that exists in the web application but is not detected by the fuzzer. | A subtle logic flaw in a payment processing function. |

Fuzzing Scope |

The specific parts of the web application that you are targeting with your fuzzing efforts. | Only fuzzing the login page or focusing on a particular API endpoint. |

Tooling

In this module, we will utilize four powerful tools designed for web application reconnaissance and vulnerability assessment. To streamline our setup, we'll install them all upfront.

Installing Go, Python and PIPX

You will require Go and Python installed for these tools. Install them as follows if you don't have them installed already.

pipx is a command-line tool designed to simplify the installation and management of Python applications. It streamlines the process by creating isolated virtual environments for each application, ensuring that dependencies don't conflict. This means you can install and run multiple Python applications without worrying about compatibility issues. pipx also makes it easy to upgrade or uninstall applications, keeping your system organized and clutter-free.

If you are using a Debian-based system (like Ubuntu), you can install Go, Python, and PIPX using the APT package manager.

Open a terminal and update your package lists to ensure you have the latest information on the newest versions of packages and their dependencies.

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo apt updateUse the following command to install Go:

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo apt install -y golangUse the following command to install Python:

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo apt install -y python3 python3-pipUse the following command to install and configure pipx:

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo apt install pipx root@htb[/htb]$ pipx ensurepath root@htb[/htb]$ sudo pipx ensurepath --globalTo ensure that Go and Python are installed correctly, you can check their versions:

root@htb[/htb]$ go version root@htb[/htb]$ python3 --version

If the installations were successful, you should see the version information for both Go and Python.

FFUF

FFUF (Fuzz Faster U Fool) is a fast web fuzzer written in Go. It excels at quickly enumerating directories, files, and parameters within web applications. Its flexibility, speed, and ease of use make it a favorite among security professionals and enthusiasts.

You can install FFUF using the following command:

Tooling

root@htb[/htb]$ go install github.com/ffuf/ffuf/v2@latest

Use Cases

| Use Case | Description |

|---|---|

Directory and File Enumeration |

Quickly identify hidden directories and files on a web server. |

Parameter Discovery |

Find and test parameters within web applications. |

Brute-Force Attack |

Perform brute-force attacks to discover login credentials or other sensitive information. |

Gobuster

Gobuster is another popular web directory and file fuzzer. It's known for its speed and simplicity, making it a great choice for beginners and experienced users alike.

You can install GoBuster using the following command:

Tooling

root@htb[/htb]$ go install github.com/OJ/gobuster/v3@latest

Use Cases

| Use Case | Description |

|---|---|

Content Discovery |

Quickly scan and find hidden web content such as directories, files, and virtual hosts. |

DNS Subdomain Enumeration |

Identify subdomains of a target domain. |

WordPress Content Detection |

Use specific wordlists to find WordPress-related content. |

FeroxBuster

FeroxBuster is a fast, recursive content discovery tool written in Rust. It's designed for brute-force discovery of unlinked content in web applications, making it particularly useful for identifying hidden directories and files. It's more of a "forced browsing" tool than a fuzzer like ffuf.

To install FeroxBuster, you can use the following command:

Tooling

root@htb[/htb]$ curl -sL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/epi052/feroxbuster/main/install-nix.sh | sudo bash -s $HOME/.local/bin

Use Cases

| Use Case | Description |

|---|---|

Recursive Scanning |

Perform recursive scans to discover nested directories and files. |

Unlinked Content Discovery |

Identify content that is not linked within the web application. |

High-Performance Scans |

Benefit from Rust's performance to conduct high-speed content discovery. |

wfuzz/wenum

wenum is an actively maintained fork of wfuzz, a highly versatile and powerful command-line fuzzing tool known for its flexibility and customization options. It's particularly well-suited for parameter fuzzing, allowing you to test a wide range of input values against web applications and uncover potential vulnerabilities in how they process those parameters.

If you are using a penetration testing Linux distribution like PwnBox or Kali, wfuzz may already be pre-installed, allowing you to use it right away if desired. However, there are currently complications when installing wfuzz, so you can substitute it with wenum instead. The commands are interchangeable, and they follow the same syntax, so you can simply replace wenum commands with wfuzz if necessary.

The following commands will use pipx, a tool for installing and managing Python applications in isolated environments, to install wenum. This ensures a clean and consistent environment for wenum, preventing any possible package conflicts:

Tooling

root@htb[/htb]$ pipx install git+https://github.com/WebFuzzForge/wenum

root@htb[/htb]$ pipx runpip wenum install setuptools

Use Cases

| Use Case | Description |

|---|---|

Directory and File Enumeration | Quickly identify hidden directories and files on a web server. |

Parameter Discovery | Find and test parameters within web applications. |

Brute-Force Attack | Perform brute-force attacks to discover login credentials or other sensitive information. |

Directory and File Fuzzing

Web applications often have directories and files that are not directly linked or visible to users. These hidden resources may contain sensitive information, backup files, configuration files, or even old, vulnerable application versions. Directory and file fuzzing aims to uncover these hidden assets, providing attackers with potential entry points or valuable information for further exploitation.

Uncovering Hidden Assets

Web applications often house a treasure trove of hidden resources — directories, files, and endpoints that aren't readily accessible through the main interface. These concealed areas might hold valuable information for attackers, including:

Sensitive data: Backup files, configuration settings, or logs containing user credentials or other confidential information.Outdated content: Older versions of files or scripts that may be vulnerable to known exploits.Development resources: Test environments, staging sites, or administrative panels that could be leveraged for further attacks.Hidden functionalities: Undocumented features or endpoints that could expose unexpected vulnerabilities.

Discovering these hidden assets is crucial for security researchers and penetration testers. It provides a deeper understanding of a web application's attack surface and potential vulnerabilities.

The Importance of Finding Hidden Assets

Uncovering these hidden gems is far from trivial. Each discovery contributes to a complete picture of the web application's structure and functionality, essential for a thorough security assessment. These hidden areas often lack the robust security measures found in public-facing components, making them prime targets for exploitation. By proactively identifying these vulnerabilities, you can stay one step ahead of malicious actors.

Even if a hidden asset doesn't immediately reveal a vulnerability, the information gleaned can prove invaluable in the later stages of a penetration test. This could include anything from understanding the underlying technology stack to discovering sensitive data that can be used for further attacks.

Directory and file fuzzing are among the most effective methods for uncovering these hidden assets. This involves systematically probing the web application with a list of potential directory and file names and analyzing the server's responses to identify valid resources.

Wordlists

Wordlists are the lifeblood of directory and file fuzzing. They provide the potential directory and file names your chosen tool will use to probe the web application. Effective wordlists can significantly increase your chances of discovering hidden assets.

Wordlists are typically compiled from various sources. This often includes scraping the web for common directory and file names, analyzing publicly available data breaches, and extracting directory information from known vulnerabilities. These wordlists are then meticulously curated, removing duplicates and irrelevant entries to ensure optimal efficiency and effectiveness during fuzzing operations. The goal is to create a comprehensive list of potential directories and file names that will likely be found on web servers, allowing you to thoroughly probe a target application for hidden assets.

The tools we've discussed – ffuf, wfuzz, etc – don't have built-in wordlists, but they are designed to work seamlessly with external wordlist files. This flexibility allows you to use pre-existing wordlists or create your own to tailor your fuzzing efforts to specific targets and scenarios.

One of the most comprehensive and widely-used collections of wordlists is SecLists. This open-source project on GitHub (https://github.com/danielmiessler/SecLists) provides a vast repository of wordlists for various security testing purposes, including directory and file fuzzing.

On pwnbox specifically, the seclists folder is located in /usr/share/seclists/, all lowercase, but other distributions might name it as per the repository, SecLists, so if a command doesn't work, double check the wordlist path.

SecLists contains wordlists for:

- Common directory and file names

- Backup files

- Configuration files

- Vulnerable scripts

- And much more

The most commonly used wordlists for fuzzing web directories and files from SecLists are:

Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt: This general-purpose wordlist contains a broad range of common directory and file names on web servers. It's an excellent starting point for fuzzing and often yields valuable results.Discovery/Web-Content/directory-list-2.3-medium.txt: This is a more extensive wordlist specifically focused on directory names. It's a good choice when you need a deeper dive into potential directories.Discovery/Web-Content/raft-large-directories.txt: This wordlist boasts a massive collection of directory names compiled from various sources. It's a valuable resource for thorough fuzzing campaigns.Discovery/Web-Content/big.txt: As the name suggests, this is a massive wordlist containing both directory and file names. It's useful when you want to cast a wide net and explore all possibilities.

Actually Fuzzing

Now that you understand the concept of wordlists, let's dive into the fuzzing process. We'll use ffuf, a powerful and flexible fuzzing tool, to uncover hidden directories and files on our target web application.

To follow along, start the target system via the question section at the bottom of the page, replacing the uses of IP:PORT with the IP:PORT for your spawned instance.

ffuf

We will use ffuf for this fuzzing task. Here's how ffuf generally works:

Wordlist: You provideffufwith a wordlist containing potential directory or file names.URL with FUZZ keyword: You construct a URL with theFUZZkeyword as a placeholder where the wordlist entries will be inserted.Requests:ffufiterates through the wordlist, replacing theFUZZkeyword in the URL with each entry and sending HTTP requests to the target web server.Response Analysis:ffufanalyzes the server's responses (status codes, content length, etc.) and filters the results based on your criteria.

For example, if you want to fuzz for directories, you might use a URL like this:

Code: http

http://localhost/FUZZ

ffuf will replace FUZZ with words like "admin," "backup," "uploads," etc., from your chosen wordlist and then send requests to http://localhost/admin, http://localhost/backup, and so on.

Directory Fuzzing

The first step is to perform directory fuzzing, which helps us discover hidden directories on the web server. Here's the ffuf command we'll use:

Directory and File Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/directory-list-2.3-medium.txt -u http://IP:PORT/FUZZ

/'___\ /'___\ /'___\

/\ \__/ /\ \__/ __ __ /\ \__/

\ \ ,__\\ \ ,__\/\ \/\ \ \ \ ,__\

\ \ \_/ \ \ \_/\ \ \_\ \ \ \ \_/

\ \_\ \ \_\ \ \____/ \ \_\

\/_/ \/_/ \/___/ \/_/

v2.1.0-dev

________________________________________________

:: Method : GET

:: URL : http://IP:PORT/FUZZ

:: Wordlist : FUZZ: /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/directory-list-2.3-medium.txt

:: Follow redirects : false

:: Calibration : false

:: Timeout : 10

:: Threads : 40

:: Matcher : Response status: 200-399

________________________________________________

[...]

w2ksvrus [Status: 301, Size: 0, Words: 1, Lines: 1, Duration: 0ms]

:: Progress: [220559/220559] :: Job [1/1] :: 100000 req/sec :: Duration: [0:00:03] :: Errors: 0 ::

-w(wordlist): Specifies the path to the wordlist we want to use. In this case, we're using a medium-sized directory list from SecLists.-u(URL): Specifies the base URL to fuzz. TheFUZZkeyword acts as a placeholder where the fuzzer will insert words from the wordlist.

The output above shows that ffuf has discovered a directory called w2ksvrus on the target web server, as indicated by the 301 (Moved Permanently) status code. This could be a potential entry point for further investigation.

File Fuzzing

While directory fuzzing focuses on finding folders, file fuzzing dives deeper into discovering specific files within those directories or even in the root of the web application. Web applications use various file types to serve content and perform different functions. Some common file extensions include:

.php: Files containing PHP code, a popular server-side scripting language..html: Files that define the structure and content of web pages..txt: Plain text files, often storing simple information or logs..bak: Backup files are created to preserve previous versions of files in case of errors or modifications..js: Files containing JavaScript code add interactivity and dynamic functionality to web pages.

By fuzzing for these common extensions with a wordlist of common file names, we increase our chances of discovering files that might be unintentionally exposed or misconfigured, potentially leading to information disclosure or other vulnerabilities.

For example, if the website uses PHP, discovering a backup file like config.php.bak could reveal sensitive information such as database credentials or API keys. Similarly, finding an old or unused script like test.php might expose vulnerabilities that attackers could exploit.

Utilize ffuf and a wordlist of common file names to search for hidden files with specific extensions:

Directory and File Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt -u http://IP:PORT/w2ksvrus/FUZZ.html -e .php,.html,.txt,.bak,.js -v

/'___\ /'___\ /'___\

/\ \__/ /\ \__/ __ __ /\ \__/

\ \ ,__\\ \ ,__\/\ \/\ \ \ \ ,__\

\ \ \_/ \ \ \_/\ \ \_\ \ \ \ \_/

\ \_\ \ \_\ \ \____/ \ \_\

\/_/ \/_/ \/___/ \/_/

v2.1.0-dev

________________________________________________

:: Method : GET

:: URL : http://IP:PORT/w2ksvrus/FUZZ.html

:: Wordlist : FUZZ: /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt

:: Extensions : .php .html .txt .bak .js

:: Follow redirects : false

:: Calibration : false

:: Timeout : 10

:: Threads : 40

:: Matcher : Response status: 200-299,301,302,307,401,403,405,500

________________________________________________

[Status: 200, Size: 111, Words: 2, Lines: 2, Duration: 0ms]

| URL | http://IP:PORT/w2ksvrus/dblclk.html

* FUZZ: dblclk

[Status: 200, Size: 112, Words: 6, Lines: 2, Duration: 0ms]

| URL | http://IP:PORT/w2ksvrus/index.html

* FUZZ: index

:: Progress: [28362/28362] :: Job [1/1] :: 0 req/sec :: Duration: [0:00:00] :: Errors: 0 ::

The ffuf output shows that it discovered two files within the /w2ksvrus directory:

dblclk.html: This file is 111 bytes in size and consists of 2 words and 2 lines. Its purpose might not be immediately apparent, but it's a potential point of interest for further investigation. Perhaps it contains hidden content or functionality.index.html: This file is slightly larger at 112 bytes and contains 6 words and 2 lines. It's likely the default index page for thew2ksvrusdirectory.

Recursive Fuzzing

So far, we've focused on fuzzing directories directly under the web root and files within a single directory. But what if our target has a complex structure with multiple nested directories? Manually fuzzing each level would be tedious and time-consuming. This is where recursive fuzzing comes in handy.

How Recursive Fuzzing Works

Recursive fuzzing is an automated way to delve into the depths of a web application's directory structure. It's a pretty basic 3 step process:

Initial Fuzzing:- The fuzzing process begins with the top-level directory, typically the web root (

/). - The fuzzer starts sending requests based on the provided wordlist containing the potential directory and file names.

- The fuzzer analyzes server responses, looking for successful results (e.g., HTTP 200 OK) that indicate the existence of a directory.

- The fuzzing process begins with the top-level directory, typically the web root (

Directory Discovery and Expansion:- When a valid directory is found, the fuzzer doesn't just note it down. It creates a new branch for that directory, essentially appending the directory name to the base URL.

- For example, if the fuzzer finds a directory named

adminat the root level, it will create a new branch likehttp://localhost/admin/. - This new branch becomes the starting point for a fresh fuzzing process. The fuzzer will again iterate through the wordlist, appending each entry to the new branch's URL (e.g.,

http://localhost/admin/FUZZ).

Iterative Depth:- The process repeats for each discovered directory, creating further branches and expanding the fuzzing scope deeper into the web application's structure.

- This continues until a specified depth limit is reached (e.g., a maximum of three levels deep) or no more valid directories are found.

Imagine a tree structure where the web root is the trunk, and each discovered directory is a branch. Recursive fuzzing systematically explores each branch, going deeper and deeper until it reaches the leaves (files) or encounters a predetermined stopping point.

Why Use Recursive Fuzzing?

Recursive fuzzing is a practical necessity when dealing with complex web applications:

Efficiency: Automating the discovery of nested directories saves significant time compared to manual exploration.Thoroughness: It systematically explores every branch of the directory structure, reducing the risk of missing hidden assets.Reduced Manual Effort: You don't need to input each new directory to fuzz manually; the tool handles the entire process.Scalability: It's particularly valuable for large-scale web applications where manual exploration would be impractical.

In essence, recursive fuzzing is about working smarter, not harder. It allows you to efficiently and comprehensively probe the depths of a web application, uncovering potential vulnerabilities that might be lurking in its hidden corners.

Recursive Fuzzing with ffuf

To follow along, start the target system via the question section at the bottom of the page, replacing the uses of IP:PORT with the IP:PORT for your spawned instance. We will be using the /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/directory-list-2.3-medium.txt wordlists for these fuzzing tasks.

Let's use ffuf to demonstrate recursive fuzzing:

Recursive Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/directory-list-2.3-medium.txt -ic -v -u http://IP:PORT/FUZZ -e .html -recursion

/'___\ /'___\ /'___\

/\ \__/ /\ \__/ __ __ /\ \__/

\ \ ,__\\ \ ,__\/\ \/\ \ \ \ ,__\

\ \ \_/ \ \ \_/\ \ \_\ \ \ \ \_/

\ \_\ \ \_\ \ \____/ \ \_\

\/_/ \/_/ \/___/ \/_/

v2.1.0-dev

________________________________________________

:: Method : GET

:: URL : http://IP:PORT/FUZZ

:: Wordlist : FUZZ: /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/directory-list-2.3-medium.txt

:: Extensions : .html

:: Follow redirects : false

:: Calibration : false

:: Timeout : 10

:: Threads : 40

:: Matcher : Response status: 200-299,301,302,307,401,403,405,500

________________________________________________

[Status: 301, Size: 0, Words: 1, Lines: 1, Duration: 0ms]

| URL | http://IP:PORT/level1

| --> | /level1/

* FUZZ: level1

[INFO] Adding a new job to the queue: http://IP:PORT/level1/FUZZ

[INFO] Starting queued job on target: http://IP:PORT/level1/FUZZ

[Status: 200, Size: 96, Words: 6, Lines: 2, Duration: 0ms]

| URL | http://IP:PORT/level1/index.html

* FUZZ: index.html

[Status: 301, Size: 0, Words: 1, Lines: 1, Duration: 0ms]

| URL | http://IP:PORT/level1/level2

| --> | /level1/level2/

* FUZZ: level2

[INFO] Adding a new job to the queue: http://IP:PORT/level1/level2/FUZZ

[Status: 301, Size: 0, Words: 1, Lines: 1, Duration: 0ms]

| URL | http://IP:PORT/level1/level3

| --> | /level1/level3/

* FUZZ: level3

[INFO] Adding a new job to the queue: http://IP:PORT/level1/level3/FUZZ

[INFO] Starting queued job on target: http://IP:PORT/level1/level2/FUZZ

[Status: 200, Size: 96, Words: 6, Lines: 2, Duration: 0ms]

| URL | http://IP:PORT/level1/level2/index.html

* FUZZ: index.html

[INFO] Starting queued job on target: http://IP:PORT/level1/level3/FUZZ

[Status: 200, Size: 126, Words: 8, Lines: 2, Duration: 0ms]

| URL | http://IP:PORT/level1/level3/index.html

* FUZZ: index.html

:: Progress: [441088/441088] :: Job [4/4] :: 100000 req/sec :: Duration: [0:00:06] :: Errors: 0 ::

Notice the addition of the -recursion flag. This tells ffuf to fuzz any directories it finds recursively. For example, if ffuf discovers an admin directory, it will automatically start a new fuzzing process on http://localhost/admin/FUZZ. In fuzzing scenarios where wordlists contain comments (lines starting with #), the ffuf -ic option proves invaluable. By enabling this option, ffuf intelligently ignores commented lines during fuzzing, preventing them from being treated as valid inputs.

The fuzzing commences at the web root (http://IP:PORT/FUZZ). Initially, ffuf identifies a directory named level1, indicated by a 301 (Moved Permanently) response. This signifies a redirection and prompts the tool to initiate a new fuzzing process within this directory, effectively branching out its search.

As ffuf recursively explores level1, it uncovers two additional directories: level2 and level3. Each is added to the fuzzing queue, expanding the search depth. Furthermore, an index.html file is discovered within level1.

The fuzzer systematically works through its queue, identifying index.html files in both level2 and level3. Notably, the index.html file within level3 stands out due to its larger file size than the others.

Further analysis reveals this file contains the flag HTB{r3curs1v3_fuzz1ng_w1ns}, signifying a successful exploration of the nested directory structure.

Be Responsible

While recursive fuzzing is a powerful technique, it can also be resource-intensive, especially on large web applications. Excessive requests can overwhelm the target server, potentially causing performance issues or triggering security mechanisms.

To mitigate these risks, ffuf provides options for fine-tuning the recursive fuzzing process:

-recursion-depth: This flag allows you to set a maximum depth for recursive exploration. For example,-recursion-depth 2limits fuzzing to two levels deep (the starting directory and its immediate subdirectories).-rate: You can control the rate at whichffufsends requests per second, preventing the server from being overloaded.-timeout: This option sets the timeout for individual requests, helping to prevent the fuzzer from hanging on unresponsive targets.

Recursive Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/directory-list-2.3-medium.txt -ic -u http://IP:PORT/FUZZ -e .html -recursion -recursion-depth 2 -rate 500

Parameter and Value Fuzzing

Building upon the discovery of hidden directories and files, we now delve into parameter and value fuzzing. This technique focuses on manipulating the parameters and their values within web requests to uncover vulnerabilities in how the application processes input.

Parameters are the messengers of the web, carrying vital information between your browser and the server that hosts the web application. They're like variables in programming, holding specific values that influence how the application behaves.

GET Parameters: Openly Sharing Information

You'll often spot GET parameters right in the URL, following a question mark (?). Multiple parameters are strung together using ampersands (&). For example:

Code: http

https://example.com/search?query=fuzzing&category=security

In this URL:

queryis a parameter with the value "fuzzing"categoryis another parameter with the value "security"

GET parameters are like postcards – their information is visible to anyone who glances at the URL. They're primarily used for actions that don't change the server's state, like searching or filtering.

POST Parameters: Behind-the-Scenes Communication

While GET parameters are like open postcards, POST parameters are more like sealed envelopes, carrying their information discreetly within the body of the HTTP request. They are not visible directly in the URL, making them the preferred method for transmitting sensitive data like login credentials, personal information, or financial details.

When you submit a form or interact with a web page that uses POST requests, the following happens:

Data Collection: The information entered into the form fields is gathered and prepared for transmission.Encoding: This data is encoded into a specific format, typicallyapplication/x-www-form-urlencodedormultipart/form-data:application/x-www-form-urlencoded: This format encodes the data as key-value pairs separated by ampersands (&), similar to GET parameters but placed within the request body instead of the URL.multipart/form-data: This format is used when submitting files along with other data. It divides the request body into multiple parts, each containing a specific piece of data or a file.

HTTP Request: The encoded data is placed within the body of an HTTP POST request and sent to the web server.Server-Side Processing: The server receives the POST request, decodes the data, and processes it according to the application's logic.

Here's a simplified example of how a POST request might look when submitting a login form:

Code: http

POST /login HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

username=your_username&password=your_password

POST: Indicates the HTTP method (POST)./login: Specifies the URL path where the form data is sent.Content-Type: Specifies how the data in the request body is encoded (application/x-www-form-urlencodedin this case).Request Body: Contains the encoded form data as key-value pairs (usernameandpassword).

Why Parameters Matter for Fuzzing

Parameters are the gateways through which you can interact with a web application. By manipulating their values, you can test how the application responds to different inputs, potentially uncovering vulnerabilities. For instance:

- Altering a product ID in a shopping cart URL could reveal pricing errors or unauthorized access to other users' orders.

- Modifying a hidden parameter in a request might unlock hidden features or administrative functions.

- Injecting malicious code into a search query could expose vulnerabilities like Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) or SQL Injection (SQLi).

wenum

In this section, we'll leverage wenum to explore both GET and POST parameters within our target web application, ultimately aiming to uncover hidden values that trigger unique responses, potentially revealing vulnerabilities.

To follow along, start the target system via the question section at the bottom of the page, replacing the uses of IP:PORT with the IP:PORT for your spawned instance. We will be using the /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt wordlists for these fuzzing tasks.

Let's first ready our tools by installing wenum to our attack host:

Parameter and Value Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ pipx install git+https://github.com/WebFuzzForge/wenum

root@htb[/htb]$ pipx runpip wenum install setuptools

Then to begin, we will use curl to manually interact with the endpoint and gain a better understanding of its behavior:

Parameter and Value Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ curl http://IP:PORT/get.php

Invalid parameter value

x:

The response tells us that the parameter x is missing. Let's try adding a value:

Parameter and Value Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ curl http://IP:PORT/get.php?x=1

Invalid parameter value

x: 1

The server acknowledges the x parameter this time but indicates that the provided value (1) is invalid. This suggests that the application is indeed checking the value of this parameter and producing different responses based on its validity. We aim to find the specific value to trigger a different and hopefully more revealing response.

Manually guessing parameter values would be tedious and time-consuming. This is where wenum comes in handy. It allows us to automate the process of testing many potential values, significantly increasing our chances of finding the correct one.

Let's use wenum to fuzz the "x" parameter's value, starting with the common.txt wordlist from SecLists:

Parameter and Value Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ wenum -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt --hc 404 -u "http://IP:PORT/get.php?x=FUZZ"

...

Code Lines Words Size Method URL

...

200 1 L 1 W 25 B GET http://IP:PORT/get.php?x=OA...

Total time: 0:00:02

Processed Requests: 4731

Filtered Requests: 4730

Requests/s: 1681

-w: Path to your wordlist.--hc 404: Hides responses with the 404 status code (Not Found), sincewenumby default will log every request it makes.http://IP:PORT/get.php?x=FUZZ: This is the target URL.wenumwill replace the parameter valueFUZZwith words from the wordlist.

Analyzing the results, you'll notice that most requests return the "Invalid parameter value" message and the incorrect value you tried. However, one line stands out:

Code: bash

200 1 L 1 W 25 B GET http://IP:PORT/get.php?x=OA...

This indicates that when the parameter x was set to the value "OA...," the server responded with a 200 OK status code, suggesting a valid input.

If you try accessing http://IP:PORT/get.php?x=OA..., you'll see the flag.

Parameter and Value Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ curl http://IP:PORT/get.php?x=OA...

HTB{...}

POST

Fuzzing POST parameters requires a slightly different approach than fuzzing GET parameters. Instead of appending values directly to the URL, we'll use ffuf to send the payloads within the request body. This enables us to test how the application handles data submitted through forms or other POST mechanisms.

Our target application also features a POST parameter named "y" within the post.php script. Let's probe it with curl to see its default behavior:

Parameter and Value Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ curl -d "" http://IP:PORT/post.php

Invalid parameter value

y:

The -d flag instructs curl to make a POST request with an empty body. The response tells us that the parameter y is expected but not provided.

As with GET parameters, manually testing POST parameter values would be inefficient. We'll use ffuf to automate this process:

Parameter and Value Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -u http://IP:PORT/post.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "y=FUZZ" -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt -mc 200 -v

/'___\ /'___\ /'___\

/\ \__/ /\ \__/ __ __ /\ \__/

\ \ ,__\\ \ ,__\/\ \/\ \ \ \ ,__\

\ \ \_/ \ \ \_/\ \ \_\ \ \ \ \_/

\ \_\ \ \_\ \ \____/ \ \_\

\/_/ \/_/ \/___/ \/_/

v2.1.0-dev

________________________________________________

:: Method : POST

:: URL : http://IP:PORT/post.php

:: Wordlist : FUZZ: /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt

:: Header : Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

:: Data : y=FUZZ

:: Follow redirects : false

:: Calibration : false

:: Timeout : 10

:: Threads : 40

:: Matcher : Response status: 200

________________________________________________

[Status: 200, Size: 26, Words: 1, Lines: 2, Duration: 7ms]

| URL | http://IP:PORT/post.php

* FUZZ: SU...

:: Progress: [4730/4730] :: Job [1/1] :: 5555 req/sec :: Duration: [0:00:01] :: Errors: 0 ::

The main difference here is the use of the -d flag, which tells ffuf that the payload ("y=FUZZ") should be sent in the request body as POST data.

Again, you'll see mostly invalid parameter responses. The correct value ("SU...") will stand out with its 200 OK status code:

Code: bash

000000326: 200 1 L 1 W 26 Ch "SU..."

Similarly, after identifying "SU..." as the correct value, validate it with curl:

Parameter and Value Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ curl -d "y=SU..." http://IP:PORT/post.php

HTB{...}

In a real-world scenario, these flags would not be present, and identifying valid parameter values might require a more nuanced analysis of the responses. However, this exercise provides a simplified demonstration of how to leverage ffuf to automate the process of testing many potential parameter values.

Virtual Host and Subdomain Fuzzing

Both virtual hosting (vhosting) and subdomains play pivotal roles in organizing and managing web content.

Virtual hosting enables multiple websites or domains to be served from a single server or IP address. Each vhost is associated with a unique domain name or hostname. When a client sends an HTTP request, the web server examines the Host header to determine which vhost's content to deliver. This facilitates efficient resource utilization and cost reduction, as multiple websites can share the same server infrastructure.

Subdomains, on the other hand, are extensions of a primary domain name, creating a hierarchical structure within the domain. They are used to organize different sections or services within a website. For example, blog.example.com and shop.example.com are subdomains of the main domain example.com. Unlike vhosts, subdomains are resolved to specific IP addresses through DNS (Domain Name System) records.

| Feature | Virtual Hosts | Subdomains |

|---|---|---|

| Identification | Identified by the Host header in HTTP requests. |

Identified by DNS records, pointing to specific IP addresses. |

| Purpose | Primarily used to host multiple websites on a single server. | Used to organize different sections or services within a website. |

| Security Risks | Misconfigured vhosts can expose internal applications or sensitive data. | Subdomain takeover vulnerabilities can occur if DNS records are mismanaged. |

Gobuster

Gobuster is a versatile command-line tool renowned for its directory/file and DNS busting capabilities. It systematically probes target web servers or domains to uncover hidden directories, files, and subdomains, making it a valuable asset in security assessments and penetration testing.

Gobuster's flexibility extends to fuzzing for various types of content:

Directories: Discover hidden directories on a web server.Files: Identify files with specific extensions (e.g.,.php,.txt,.bak).Subdomains: Enumerate subdomains of a given domain.Virtual Hosts (vhosts): Uncover hidden virtual hosts by manipulating theHostheader.

Gobuster VHost Fuzzing

While gobuster is primarily known for directory and file enumeration, its capabilities extend to virtual host (vhost) discovery, making it a valuable tool in assessing the security posture of a web server.

To follow along, start the target system via the question section at the bottom of the page. Add the specified vhost to your hosts file using the command below, replacing IP with the IP address of your spawned instance. We will be using the /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt wordlists for these fuzzing tasks.

Virtual Host and Subdomain Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ echo "IP inlanefreight.htb" | sudo tee -a /etc/hosts

Let's dissect the Gobuster vhost fuzzing command:

Virtual Host and Subdomain Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ gobuster vhost -u http://inlanefreight.htb:81 -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt --append-domain

gobuster vhost: This flag activatesGobuster's vhost fuzzing mode, instructing it to focus on discovering virtual hosts rather than directories or files.-u http://inlanefreight.htb:81: This specifies the base URL of the target server.Gobusterwill use this URL as the foundation for constructing requests with different vhost names. In this example, the target server is located atinlanefreight.htband listens on port 81.-w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt: This points to the wordlist file thatGobusterwill use to generate potential vhost names. Thecommon.txtwordlist from SecLists contains a collection of commonly used vhost names and subdomains.--append-domain: This crucial flag instructsGobusterto append the base domain (inlanefreight.htb) to each word in the wordlist. This ensures that theHostheader in each request includes a complete domain name (e.g.,admin.inlanefreight.htb), which is essential for vhost discovery.

In essence, Gobuster takes each word from the wordlist, appends the base domain to it, and then sends an HTTP request to the target URL with that modified Host header. By analyzing the server's responses (e.g., status codes, response size), Gobuster can identify valid vhosts that might not be publicly advertised or documented.

Running the command will execute a vhost scan against the target:

Virtual Host and Subdomain Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ gobuster vhost -u http://inlanefreight.htb:81 -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt --append-domain

===============================================================

Gobuster v3.6

by OJ Reeves (@TheColonial) & Christian Mehlmauer (@firefart)

===============================================================

[+] Url: http://inlanefreight.htb:81

[+] Method: GET

[+] Threads: 10

[+] Wordlist: /usr/share/SecLists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt

[+] User Agent: gobuster/3.6

[+] Timeout: 10s

[+] Append Domain: true

===============================================================

Starting gobuster in VHOST enumeration mode

===============================================================

Found: .git/logs/.inlanefreight.htb:81 Status: 400 [Size: 157]

...

Found: admin.inlanefreight.htb:81 Status: 200 [Size: 100]

Found: android/config.inlanefreight.htb:81 Status: 400 [Size: 157]

...

Progress: 4730 / 4730 (100.00%)

===============================================================

Finished

===============================================================

After the scan has been completed, we see a list of the results. Of particular interest are the vhosts with the 200 status code. In HTTP, a 200 status indicates a successful response, suggesting that the vhost is valid and accessible. For instance, the line Found: admin.inlanefreight.htb:81 Status: 200 [Size: 100] indicates that the vhost admin.inlanefreight.htb was found and responded to successfully.

Gobuster Subdomain Fuzzing

While often associated with vhost and directory discovery, Gobuster also excels at subdomain enumeration, a crucial step in mapping the attack surface of a target domain. By systematically testing variations of potential subdomain names, Gobuster can uncover hidden or forgotten subdomains that might host valuable information or vulnerabilities.

Let's break down the Gobuster subdomain fuzzing command:

Virtual Host and Subdomain Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ gobuster dns -d inlanefreight.com -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/DNS/subdomains-top1million-5000.txt

gobuster dns: ActivatesGobuster'sDNS fuzzing mode, directing it to focus on discovering subdomains.-d inlanefreight.com: Specifies the target domain (e.g.,inlanefreight.com) for which you want to discover subdomains.-w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/DNS/subdomains-top1million-5000.txt: This points to the wordlist file thatGobusterwill use to generate potential subdomain names. In this example, we're using a wordlist containing the top 5000 most common subdomains.

Under the hood, Gobuster works by generating subdomain names based on the wordlist, appending them to the target domain, and then attempting to resolve those subdomains using DNS queries. If a subdomain resolves to an IP address, it is considered valid and included in the output.

Running this command, Gobuster might produce output similar to:

Virtual Host and Subdomain Fuzzing

root@htb[/htb]$ gobuster dns -d inlanefreight.com -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/DNS/subdomains-top1million-5000.txt

===============================================================

Gobuster v3.6

by OJ Reeves (@TheColonial) & Christian Mehlmauer (@firefart)

===============================================================

[+] Domain: inlanefreight.com

[+] Threads: 10

[+] Timeout: 1s

[+] Wordlist: /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/DNS/subdomains-top1million-5000.txt

===============================================================

Starting gobuster in DNS enumeration mode

===============================================================

Found: www.inlanefreight.com

Found: blog.inlanefreight.com

...

Progress: 4989 / 4990 (99.98%)

===============================================================

Finished

===============================================================

In the output, each line prefixed with "Found:" indicates a valid subdomain discovered by Gobuster.

Filtering Fuzzing Output

Web fuzzing tools like gobuster, ffuf, and wfuzz are designed to perform comprehensive scans, often generating a vast amount of data. Sifting through this output to identify the most relevant findings can be a daunting task. However, these tools offer powerful filtering mechanisms to streamline your analysis and focus on the results that matter most.

Gobuster

Gobuster offers various filtering options depending on the module being run, to help you focus on specific responses and streamline your analysis. There is a small caveat, the -s and -b options are only available in the dir fuzzing mode.

| Flag | Description | Example Scenario |

|---|---|---|

-s (include) |

Include only responses with the specified status codes (comma-separated). | You're looking for redirects, so you filter for codes 301,302,307 |

-b (exclude) |

Exclude responses with the specified status codes (comma-separated). | The server returns many 404 errors. Exclude them with -b 404 |

--exclude-length |

Exclude responses with specific content lengths (comma-separated, supports ranges). | You're not interested in 0-byte or 404-byte responses, so use --exclude-length 0,404 |

By strategically combining these filtering options, you can tailor Gobuster's output to your specific needs and focus on the most relevant results for your security assessments.

Filtering Fuzzing Output

# Find directories with status codes 200 or 301, but exclude responses with a size of 0 (empty responses)

root@htb[/htb]$ gobuster dir -u http://example.com/ -w wordlist.txt -s 200,301 --exclude-length 0

FFUF

FFUF offers a highly customizable filtering system, enabling precise control over the displayed output. This allows you to efficiently sift through potentially large amounts of data and focus on the most relevant findings. FFUF's filtering options are categorized into multiple types, each serving a specific purpose in refining your results.

| Flag | Description | Example Scenario |

|---|---|---|

-mc (match code) |

Include only responses that match the specified status codes. You can provide a single code, multiple codes separated by commas, or ranges of codes separated by hyphens (e.g., 200,204,301, 400-499). The default behavior is to match codes 200-299, 301, 302, 307, 401, 403, 405, and 500. |

After fuzzing, you notice many 302 (Found) redirects, but you're primarily interested in 200 (OK) responses. Use -mc 200 to isolate these. |

-fc (filter code) |

Exclude responses that match the specified status codes, using the same format as -mc. This is useful for removing common error codes like 404 Not Found. |

A scan returns many 404 errors. Use -fc 404 to remove them from the output. |

-fs (filter size) |

Exclude responses with a specific size or range of sizes. You can specify single sizes or ranges using hyphens (e.g., -fs 0 for empty responses, -fs 100-200 for responses between 100 and 200 bytes). |

You suspect the interesting responses will be larger than 1KB. Use -fs 0-1023 to filter out smaller responses. |

-ms (match size) |

Include only responses that match a specific size or range of sizes, using the same format as -fs. |

You are looking for a backup file that you know is exactly 3456 bytes in size. Use -ms 3456 to find it. |

-fw (filter out number of words in response) |

Exclude responses containing the specified number of words in the response. | You're filtering out a specific number of words from the responses. Use -fw 219 to filter for responses containing that amount of words. |

-mw (match word count) |

Include only responses that have the specified amount of words in the response body. | You're looking for short, specific error messages. Use -mw 5-10 to filter for responses with 5 to 10 words. |

-fl (filter line) |

Exclude responses with a specific number of lines or range of lines. For example, -fl 5 will filter out responses with 5 lines. |

You notice a pattern of 10-line error messages. Use -fl 10 to filter them out. |

-ml (match line count) |

Include only responses that have the specified amount of lines in the response body. | You're looking for responses with a specific format, such as 20 lines. Use -ml 20 to isolate them. |

-mt (match time) |

Include only responses that meet a specific time-to-first-byte (TTFB) condition. This is useful for identifying responses that are unusually slow or fast, potentially indicating interesting behavior. | The application responds slowly when processing certain inputs. Use -mt >500 to find responses with a TTFB greater than 500 milliseconds. |

You can combine multiple filters. For example:

Filtering Fuzzing Output

# Find directories with status code 200, based on the amount of words, and a response size greater than 500 bytes

root@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -u http://example.com/FUZZ -w wordlist.txt -mc 200 -fw 427 -ms >500

# Filter out responses with status codes 404, 401, and 302

root@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -u http://example.com/FUZZ -w wordlist.txt -fc 404,401,302

# Find backup files with the .bak extension and size between 10KB and 100KB

root@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -u http://example.com/FUZZ.bak -w wordlist.txt -fs 0-10239 -ms 10240-102400

# Discover endpoints that take longer than 500ms to respond

root@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -u http://example.com/FUZZ -w wordlist.txt -mt >500

wenum

wenum offers a robust filtering system to help you manage and refine the vast amount of data generated during fuzzing. You can filter based on status codes, response size/character count, word count, line count, and even regular expressions.

| Flag | Description | Example Scenario |

|---|---|---|

--hc (hide code) |

Exclude responses that match the specified status codes. | After fuzzing, the server returned many 400 Bad Request errors. Use --hc 400 to hide them and focus on other responses. |

--sc (show code) |

Include only responses that match the specified status codes. | You are only interested in successful requests (200 OK). Use --sc 200 to filter the results accordingly. |

--hl (hide length) |

Exclude responses with the specified content length (in lines). | The server returns verbose error messages with many lines. Use --hl with a high value to hide these and focus on shorter responses. |

--sl (show length) |

Include only responses with the specified content length (in lines). | You suspect a specific response with a known line count is related to a vulnerability. Use --sl to pinpoint it. |

--hw (hide word) |

Exclude responses with the specified number of words. | The server includes common phrases in many responses. Use --hw to filter out responses with those word counts. |

--sw (show word) |

Include only responses with the specified number of words. | You are looking for short error messages. Use --sw with a low value to find them. |

--hs (hide size) |

Exclude responses with the specified response size (in bytes or characters). | The server sends large files for valid requests. Use --hs to filter out these large responses and focus on smaller ones. |

--ss (show size) |

Include only responses with the specified response size (in bytes or characters). | You are looking for a specific file size. Use --ss to find it. |

--hr (hide regex) |

Exclude responses whose body matches the specified regular expression. | Filter out responses containing the "Internal Server Error" message. Use --hr "Internal Server Error". |

--sr (show regex) |

Include only responses whose body matches the specified regular expression. | Filter for responses containing the string "admin" using --sr "admin". |

--filter/--hard-filter |

General-purpose filter to show/hide responses or prevent their post-processing using a regular expression. | --filter "Login" will show only responses containing "Login", while --hard-filter "Login" will hide them and prevent any plugins from processing them. |

You can combine multiple filters. For example:

Filtering Fuzzing Output

# Show only successful requests and redirects:

root@htb[/htb]$ wenum -w wordlist.txt --sc 200,301,302 -u https://example.com/FUZZ

# Hide responses with common error codes:

root@htb[/htb]$ wenu -w wordlist.txt --hc 404,400,500 -u https://example.com/FUZZ

# Show only short error messages (responses with 5-10 words):

root@htb[/htb]$ wenum -w wordlist.txt --sw 5-10 -u https://example.com/FUZZ

# Hide large files and focus on smaller responses:

root@htb[/htb]$ wenum -w wordlist.txt --hs 10000 -u https://example.com/FUZZ

# Filter for responses containing specific information:

root@htb[/htb]$ wenum -w wordlist.txt --sr "admin\|password" -u https://example.com/FUZZ

Feroxbuster

Feroxbuster's filtering system is designed to be both powerful and flexible, enabling you to fine-tune the results you receive during a scan. It offers a variety of filters that operate on both the request and response levels.

| Flag | Description | Example Scenario |

|---|---|---|

--dont-scan (Request) |

Exclude specific URLs or patterns from being scanned (even if found in links during recursion). | You know the /uploads directory contains only images, so you can exclude it using --dont-scan /uploads. |

-S, --filter-size |

Exclude responses based on their size (in bytes). You can specify single sizes or comma-separated ranges. | You've noticed many 1KB error pages. Use -S 1024 to exclude them. |

-X, --filter-regex |

Exclude responses whose body or headers match the specified regular expression. | Filter out pages with a specific error message using -X "Access Denied". |

-W, --filter-words |

Exclude responses with a specific word count or range of word counts. | Eliminate responses with very few words (e.g., error messages) using -W 0-10. |

-N, --filter-lines |

Exclude responses with a specific line count or range of line counts. | Filter out long, verbose pages with -N 50-. |

-C, --filter-status |

Exclude responses based on specific HTTP status codes. This operates as a denylist. | Suppress common error codes like 404 and 500 using -C 404,500. |

--filter-similar-to |

Exclude responses that are similar to a given webpage. | Remove duplicate or near-duplicate pages based on a reference page using --filter-similar-to error.html. |

-s, --status-codes |

Include only responses with the specified status codes. This operates as an allowlist (default: all). | Focus on successful responses using -s 200,204,301,302. |

You can combine multiple filters. For example:

Filtering Fuzzing Output

# Find directories with status code 200, excluding responses larger than 10KB or containing the word "error"

root@htb[/htb]$ feroxbuster --url http://example.com -w wordlist.txt -s 200 -S 10240 -X "error"

A Quick Demonstration

To follow along, start the target system via the question section at the bottom of the page. Add the specified vhost to your hosts file using the command below, replacing IP with the IP address of your spawned instance. We will be using the /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt wordlists for these fuzzing tasks.

Throughout the module so far, you might have noticed some of the commands have been using some sort of result filtering, or the fuzzers themselves are applying some sort of filtering. For example, for POST fuzzing with ffuf, if we remove the match code filter, ffuf will default to a series of other filters.

Filtering Fuzzing Output

root@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -u http://IP:PORT/post.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "y=FUZZ" -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt -v

/'___\ /'___\ /'___\

/\ \__/ /\ \__/ __ __ /\ \__/

\ \ ,__\\ \ ,__\/\ \/\ \ \ \ ,__\

\ \ \_/ \ \ \_/\ \ \_\ \ \ \ \_/

\ \_\ \ \_\ \ \____/ \ \_\

\/_/ \/_/ \/___/ \/_/

v2.1.0-dev

________________________________________________

:: Method : POST

:: URL : http://IP:PORT/post.php

:: Wordlist : FUZZ: /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt

:: Header : Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

:: Data : y=FUZZ

:: Follow redirects : false

:: Calibration : false

:: Timeout : 10

:: Threads : 40

:: Matcher : Response status: 200-299,301,302,307,401,403,405,500

________________________________________________

In the output above, the line :: Matcher : Response status: 200-299,301,302,307,401,403,405,500 indicates that, by default, ffuf matches only those specific status codes. This intentional filtering minimizes the noise generated by 404 NOT FOUND responses, ensuring that the results of interest remain prominent.

To illustrate the potential issue of not filtering, let's run the same scan while matching all status codes using the -mc all flag:

Filtering Fuzzing Output

root@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -u http://IP:PORT/post.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "y=FUZZ" -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt -v -mc all

/'___\ /'___\ /'___\

/\ \__/ /\ \__/ __ __ /\ \__/

\ \ ,__\\ \ ,__\/\ \/\ \ \ \ ,__\

\ \ \_/ \ \ \_/\ \ \_\ \ \ \ \_/

\ \_\ \ \_\ \ \____/ \ \_\

\/_/ \/_/ \/___/ \/_/

v2.1.0-dev

________________________________________________

:: Method : POST

:: URL : http://IP:PORT/post.php

:: Wordlist : FUZZ: /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/common.txt

:: Header : Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

:: Data : y=FUZZ

:: Follow redirects : false

:: Calibration : false

:: Timeout : 10

:: Threads : 40

:: Matcher : Response status: all

________________________________________________

[Status: 404, Size: 36, Words: 4, Lines: 3, Duration: 1ms]

| URL | http://IP:PORT/post.php

* FUZZ: .cache

[Status: 404, Size: 43, Words: 4, Lines: 3, Duration: 2ms]

| URL | http://IP:PORT/post.php

* FUZZ: .bash_history

[Status: 404, Size: 34, Words: 4, Lines: 3, Duration: 2ms]

| URL | http://IP:PORT/post.php

* FUZZ: .cvs

[Status: 404, Size: 42, Words: 4, Lines: 3, Duration: 2ms]

| URL | http://IP:PORT/post.php

* FUZZ: .git-rewrite