The cheat sheet is a useful command reference for this module.

| Command | Description |

man <tool> | Opens man pages for the specified tool. |

<tool> -h | Prints the help page of the tool. |

apropos <keyword> | Searches through man pages' descriptions for instances of a given keyword. |

cat | Concatenate and print files. |

whoami | Displays current username. |

id | Returns users identity. |

hostname | Sets or prints the name of the current host system. |

uname | Prints operating system name. |

pwd | Returns working directory name. |

ifconfig | The ifconfig utility is used to assign or view an address to a network interface and/or configure network interface parameters. |

ip | Ip is a utility to show or manipulate routing, network devices, interfaces, and tunnels. |

netstat | Shows network status. |

ss | Another utility to investigate sockets. |

ps | Shows process status. |

who | Displays who is logged in. |

env | Prints environment or sets and executes a command. |

lsblk | Lists block devices. |

lsusb | Lists USB devices. |

lsof | Lists opened files. |

lspci | Lists PCI devices. |

sudo | Execute command as a different user. |

su | The su utility requests appropriate user credentials via PAM and switches to that user ID (the default user is the superuser). A shell is then executed. |

useradd | Creates a new user or update default new user information. |

userdel | Deletes a user account and related files. |

usermod | Modifies a user account. |

addgroup | Adds a group to the system. |

delgroup | Removes a group from the system. |

passwd | Changes user password. |

dpkg | Install, remove and configure Debian-based packages. |

apt | High-level package management command-line utility. |

aptitude | Alternative to apt. |

snap | Install, remove and configure snap packages. |

gem | Standard package manager for Ruby. |

pip | Standard package manager for Python. |

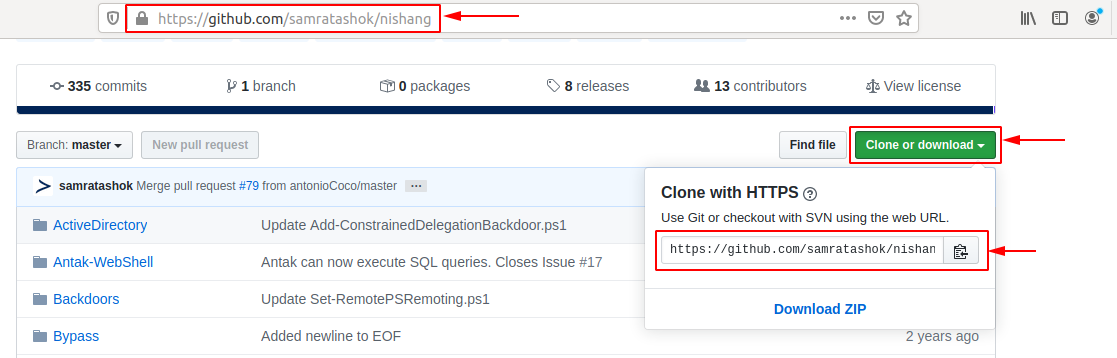

git | Revision control system command-line utility. |

systemctl | Command-line based service and systemd control manager. |

ps | Prints a snapshot of the current processes. |

journalctl | Query the systemd journal. |

kill | Sends a signal to a process. |

bg | Puts a process into background. |

jobs | Lists all processes that are running in the background. |

fg | Puts a process into the foreground. |

curl | Command-line utility to transfer data from or to a server. |

wget | An alternative to curl that downloads files from FTP or HTTP(s) server. |

python3 -m http.server | Starts a Python3 web server on TCP port 8000. |

ls | Lists directory contents. |

cd | Changes the directory. |

clear | Clears the terminal. |

touch | Creates an empty file. |

mkdir | Creates a directory. |

tree | Lists the contents of a directory recursively. |

mv | Move or rename files or directories. |

cp | Copy files or directories. |

nano | Terminal based text editor. |

which | Returns the path to a file or link. |

find | Searches for files in a directory hierarchy. |

updatedb | Updates the locale database for existing contents on the system. |

locate | Uses the locale database to find contents on the system. |

more | Pager that is used to read STDOUT or files. |

less | An alternative to more with more features. |

head | Prints the first ten lines of STDOUT or a file. |

tail | Prints the last ten lines of STDOUT or a file. |

sort | Sorts the contents of STDOUT or a file. |

grep | Searches for specific results that contain given patterns. |

cut | Removes sections from each line of files. |

tr | Replaces certain characters. |

column | Command-line based utility that formats its input into multiple columns. |

awk | Pattern scanning and processing language. |

sed | A stream editor for filtering and transforming text. |

wc | Prints newline, word, and byte counts for a given input. |

chmod | Changes permission of a file or directory. |

chown | Changes the owner and group of a file or directory. |

Many events led up to creating the first Linux kernel and, ultimately, the Linux operating system (OS), starting with the Unix operating system's release by Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie (whom both worked for AT\&T at the time) in 1970. The Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) was released in 1977, but since it contained the Unix code owned by AT\&T, a resulting lawsuit limited the development of BSD. Richard Stallman started the GNU project in 1983. His goal was to create a free Unix-like operating system, and part of his work resulted in the GNU General Public License (GPL) being created. Projects by others over the years failed to result in a working, free kernel that would become widely adopted until the creation of the Linux kernel.

At first, Linux was a personal project started in 1991 by a Finnish student named Linus Torvalds. His goal was to create a new, free operating system kernel. Over the years, the Linux kernel has gone from a small number of files written in C under licensing that prohibited commercial distribution to the latest version with over 23 million source code lines (comments excluded), licensed under the GNU General Public License v2.

Linux is available in over 600 distributions (or an operating system based on the Linux kernel and supporting software and libraries). Some of the most popular and well-known being Ubuntu, Debian, Fedora, OpenSUSE, elementary, Manjaro, Gentoo Linux, RedHat, and Linux Mint.

Linux is generally considered more secure than other operating systems, and while it has had many kernel vulnerabilities in the past, it is becoming less and less frequent. It is less susceptible to malware than Windows operating systems and is very frequently updated. Linux is also very stable and generally affords very high performance to the end-user. However, it can be more difficult for beginners and does not have as many hardware drivers as Windows.

Since Linux is free and open-source, the source code can be modified and distributed commercially or non-commercially by anyone. Linux-based operating systems run on servers, mainframes, desktops, embedded systems such as routers, televisions, video game consoles, and more. The overall Android operating system that runs on smartphones and tablets is based on the Linux kernel, and because of this, Linux is the most widely installed operating system.

Linux is an operating system like Windows, iOS, Android, or macOS. An OS is software that manages all of the hardware resources associated with our computer. That means that an OS manages the whole communication between software and hardware. Also, there exist many different distributions (distro). It is like a version of Windows operating systems.

With the interactive instances, we get access to the Pwnbox, a customized version of Parrot OS. This will be the primary OS we will work with through the modules. Parrot OS is a Debian-based Linux distribution that focuses on security, privacy, and development.

Linux follows five core principles:

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

Everything is a file |

All configuration files for the various services running on the Linux operating system are stored in one or more text files. |

Small, single-purpose programs |

Linux offers many different tools that we will work with, which can be combined to work together. |

Ability to chain programs together to perform complex tasks |

The integration and combination of different tools enable us to carry out many large and complex tasks, such as processing or filtering specific data results. |

Avoid captive user interfaces |

Linux is designed to work mainly with the shell (or terminal), which gives the user greater control over the operating system. |

Configuration data stored in a text file |

An example of such a file is the /etc/passwd file, which stores all users registered on the system. |

| Component | Description |

Bootloader | A piece of code that runs to guide the booting process to start the operating system. Parrot Linux uses the GRUB Bootloader. |

OS Kernel | The kernel is the main component of an operating system. It manages the resources for system's I/O devices at the hardware level. |

Daemons | Background services are called "daemons" in Linux. Their purpose is to ensure that key functions such as scheduling, printing, and multimedia are working correctly. These small programs load after we booted or log into the computer. |

OS Shell | The operating system shell or the command language interpreter (also known as the command line) is the interface between the OS and the user. This interface allows the user to tell the OS what to do. The most commonly used shells are Bash, Tcsh/Csh, Ksh, Zsh, and Fish. |

Graphics server | This provides a graphical sub-system (server) called "X" or "X-server" that allows graphical programs to run locally or remotely on the X-windowing system. |

Window Manager | Also known as a graphical user interface (GUI). There are many options, including GNOME, KDE, MATE, Unity, and Cinnamon. A desktop environment usually has several applications, including file and web browsers. These allow the user to access and manage the essential and frequently accessed features and services of an operating system. |

Utilities | Applications or utilities are programs that perform particular functions for the user or another program. |

The Linux operating system can be broken down into layers:

| Layer | Description |

Hardware | Peripheral devices such as the system's RAM, hard drive, CPU, and others. |

Kernel | The core of the Linux operating system whose function is to virtualize and control common computer hardware resources like CPU, allocated memory, accessed data, and others. The kernel gives each process its own virtual resources and prevents/mitigates conflicts between different processes. |

Shell | A command-line interface (CLI), also known as a shell that a user can enter commands into to execute the kernel's functions. |

System Utility | Makes available to the user all of the operating system's functionality. |

The Linux operating system is structured in a tree-like hierarchy and is documented in the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS). Linux is structured with the following standard top-level directories:

| Path | Description |

/ | The top-level directory is the root filesystem and contains all of the files required to boot the operating system before other filesystems are mounted as well as the files required to boot the other filesystems. After boot, all of the other filesystems are mounted at standard mount points as subdirectories of the root. |

/bin | Contains essential command binaries. |

/boot | Consists of the static bootloader, kernel executable, and files required to boot the Linux OS. |

/dev | Contains device files to facilitate access to every hardware device attached to the system. |

/etc | Local system configuration files. Configuration files for installed applications may be saved here as well. |

/home | Each user on the system has a subdirectory here for storage. |

/lib | Shared library files that are required for system boot. |

/media | External removable media devices such as USB drives are mounted here. |

/mnt | Temporary mount point for regular filesystems. |

/opt | Optional files such as third-party tools can be saved here. |

/root | The home directory for the root user. |

/sbin | This directory contains executables used for system administration (binary system files). |

/tmp | The operating system and many programs use this directory to store temporary files. This directory is generally cleared upon system boot and may be deleted at other times without any warning. |

/usr | Contains executables, libraries, man files, etc. |

/var | This directory contains variable data files such as log files, email in-boxes, web application related files, cron files, and more. |

\ Linux distributions - or distros - are operating systems based on the Linux kernel. They are used for various purposes, from servers and embedded devices to desktop computers and mobile phones. Each Linux distribution is different, with its own set of features, packages, and tools. Some popular examples include:

Many users choose Linux for their desktop computers because it is free, open source, and highly customizable. Ubuntu and Fedora are two popular choices for desktop Linux and beginners. It is also widely used as a server operating system because it is secure, stable, and reliable and comes with frequent and regular updates. Finally, we, as cybersecurity specialists, often prefer Linux because it is open source, meaning its source code is available for scrutiny and customization. Because of such customization, we can optimize and customize our Linux distribution the way we want and configure it for specific use cases only if necessary.

We can use those distros everywhere, including (web) servers, mobile devices, embedded systems, cloud computing, and desktop computing. For cyber security specialists, some of the most popular Linux distributions are but are not limited to:

| ParrotOS | Ubuntu | Debian |

| Raspberry Pi OS | CentOS | BackBox |

| BlackArch | Pentoo |

The main differences between the various Linux distributions are the included packages, the user interface, and the tools available. Kali Linux is the most popular distribution for cyber security specialists, including a wide range of security-focused tools and packages. Ubuntu is widespread for desktop users, while Debian is popular for servers and embedded systems. Finally, red Hat Enterprise Linux and CentOS are popular for enterprise-level computing.

Debian is a widely used and well-respected Linux distribution known for its stability and reliability. It is used for various purposes, including desktop computing, servers, and embedded system. It uses an Advanced Package Tool (apt) package management system to handle software updates and security patches. The package management system helps keep the system up-to-date and secure by automatically downloading and installing security updates as soon as they are available. This can be executed manually or set up automatically.

Debian can have a steeper learning curve than other distributions, but it is widely regarded as one of the most flexible and customizable Linux distros. The configuration and setup can be complex, but it also provides excellent control over the system, which can be good for advanced users. The more control we have over a Linux system, the more complex it feels to become. However, it just feels that way compared to the options and possibilities we get. Without learning it with the required depth, we might spend way more time configuring “easy” tasks and processes than when we would learn to use a few commands and tools more in-depth. We will see it in the Filter Contents and Find Files and Directories sections.

Stability and reliability are key strengths of Debian. The distribution is known for its long-term support releases, which can provide updates and security patches for up to five years. This can be especially important for servers and other systems that must be up and running 24/7. It has had some vulnerabilities, but the development community has quickly released patches and security updates. In addition, Debian has a strong commitment to security and privacy, and the distribution has a well-established security track record. Debian is a versatile and reliable Linux distribution that is widely used for a range of purposes. Its stability, reliability, and commitment to security make it an attractive choice for various use cases, including cyber security.

\

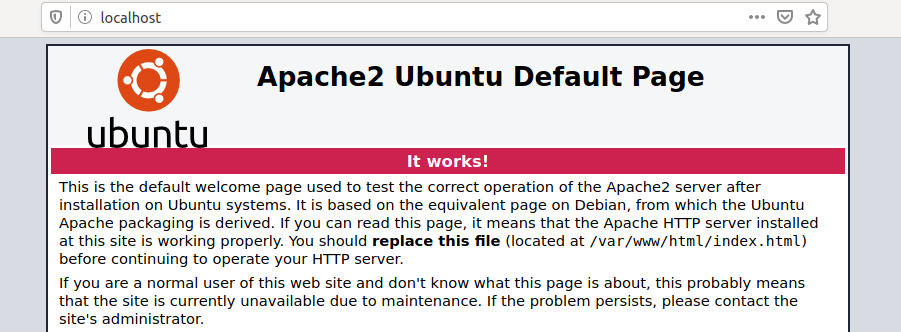

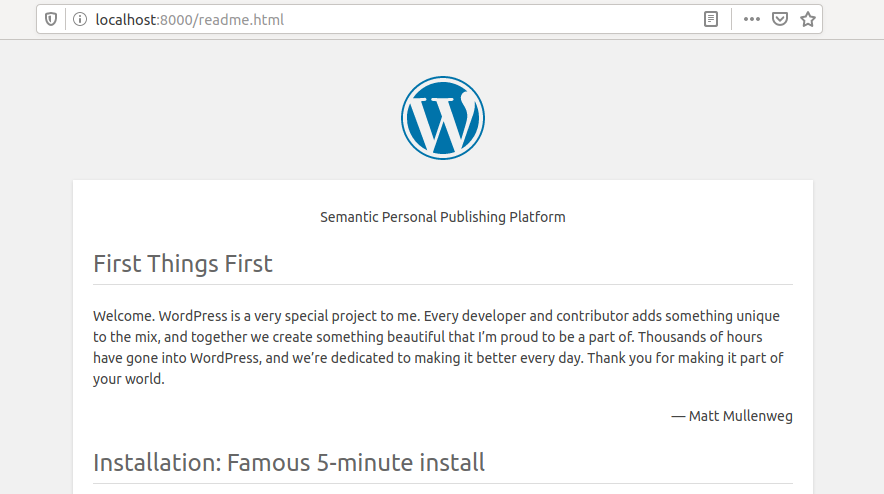

It is crucial to learn how to use the Linux shell, as there are many servers based on Linux. These are often used because Linux is less error-prone as opposed to Windows servers. For example, web servers are often based on Linux. Knowing how to use the operating system to control it effectively requires understanding and mastering Linux’s essential part, the Shell. When we first switched from Windows to Linux, does it look something like this:

A Linux terminal, also called a shell or command line, provides a text-based input/output (I/O) interface between users and the kernel for a computer system. The term console is also typical but does not refer to a window but a screen in text mode. In the terminal window, commands can be executed to control the system.

We can think of a shell as a text-based GUI in which we enter commands to perform actions like navigating to other directories, working with files, and obtaining information from the system but with way more capabilities.

Terminal emulation is software that emulates the function of a terminal. It allows the use of text-based programs within a graphical user interface (GUI). There are also so-called command-line interfaces (CLI) that run as additional terminals in one terminal. In short, a terminal serves as an interface to the shell interpreter.

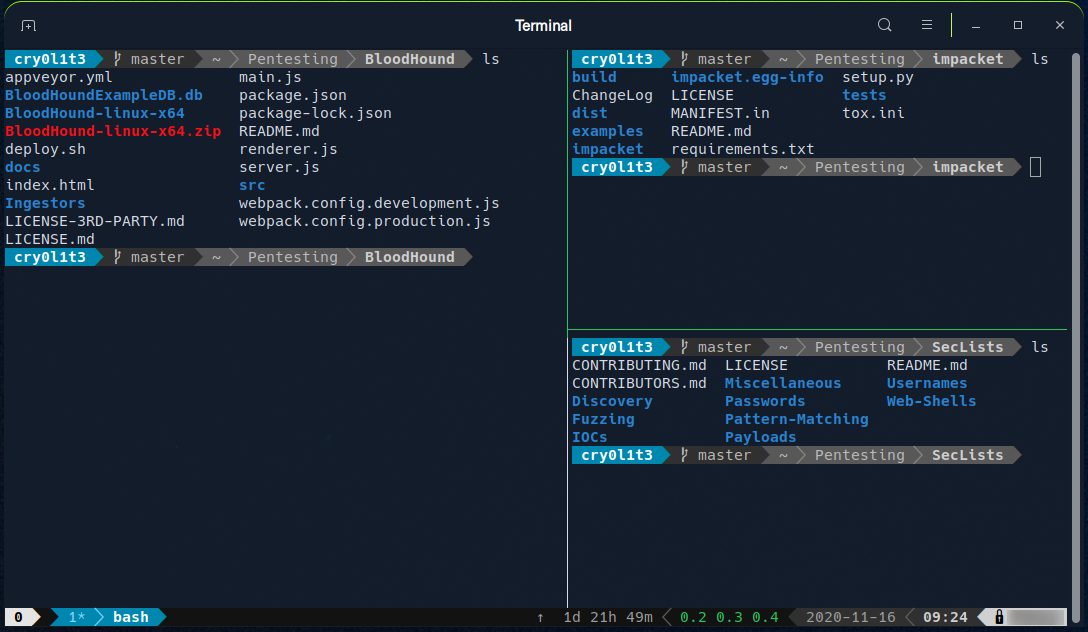

Terminal emulators and multiplexers are beneficial extensions for the terminal. They provide us with different methods and functions to work with the terminal, such as splitting the terminal into one window, working in multiple directories, creating different workspaces, and much more. An example of the use of such a multiplexer called Tmux could look something like this:

The most commonly used shell in Linux is the Bourne-Again Shell (BASH), and is part of the GNU project. Everything we do through the GUI we can do with the shell. The shell gives us many more possibilities to interact with programs and processes to get information faster. Besides, many processes can be easily automated with smaller or larger scripts that make manual work much easier.

Besides Bash, there also exist other shells like Tcsh/Csh, Ksh, Zsh, Fish shell and others.

The bash prompt is easy to understand and, by default, includes information such as the user, hostname, and current working directory. It is a string of characters displayed on the terminal screen that indicates that the system is ready for our input. It typically includes information such as the current user, the computer’s hostname, and the current working directory. The prompt is usually displayed on a new line, and the cursor is positioned after the prompt, ready for the user to start typing a command.

It can be customized to provide useful information to the user. The format can look something like this:

<username>@<hostname><current working directory>$

The home directory for a user is marked with a tilde <~> and is the default folder when we log in.

<username>@<hostname>[~]$

The dollar sign, in this case, stands for a user. As soon as we log in as root, the character changes to a hash <#> and looks like this:

root@htb[/htb]#

For example, when we upload and run a shell on the target system, we may not see the username, hostname, and current working directory. This may be due to the PS1 variable in the environment not being set correctly. In this case, we would see the following prompts:

In addition to providing basic information like the current user and working directory, we can customize to display other information in the prompt, such as the IP address, date, time, the exit status of the last command, and more. This is especially useful for us during our penetration tests because we can use various tools and possibilities like script or the .bash_history to filter and print all the commands we used and sort them by date and time. For example, the prompt could be set to display the full path of the current working directory instead of just the current directory name, which can also include the target’s IP address if we work organized.

The prompt can be customized using special characters and variables in the shell’s configuration file (.bashrc for the Bash shell). For example, we can use: the \u character to represent the current username, \h for the hostname, and \w for the current working directory.

| Special Character | Description |

\d | Date (Mon Feb 6) |

\D{%Y-%m-%d} | Date (YYYY-MM-DD) |

\H | Full hostname |

\j | Number of jobs managed by the shell |

| Newline | |

| Carriage return | |

\s | Name of the shell |

| Current time 24-hour (HH:MM:SS) | |

| Current time 12-hour (HH:MM:SS) | |

\@ | Current time |

\u | Current username |

\w | Full path of the current working directory |

Customizing the prompt can be a useful way to make your terminal experience more personalized and efficient. It can also be a helpful tool for troubleshooting and problem-solving, as it can provide important information about the system’s state at any given time.

In addition to customizing the prompt, we can customize their terminal environment with different color schemes, fonts, and other settings to make their work environment more visually appealing and easier to use.

However, we see the same as when working on the Windows GUI here. We are logged in as a user on a computer with a specific name, and we know which directory we are in when we navigate through our system. Bash prompt can also be customized and changed to our own needs. The adjustment of the bash prompt is outside the scope of this module. However, we can look at the bash-prompt-generator and powerline, which gives us the possibility to adapt our prompt to our needs.

We will always stumble across tools whose optional parameters we do not know from memory or tools we have never seen before. Therefore it is vital to know how we can help ourselves to get familiar with those tools. The first two ways are the man pages and the help functions. It is always a good idea to familiarize ourselves with the tool we want to try first. We will also learn some possible tricks with some of the tools that we thought were not possible. In the man pages, we will find the detailed manuals with detailed explanations.

Syntax:

root@htb[/htb]$ man <tool>

Let us have a look at an example:

Example:

root@htb[/htb]$ man curl

curl(1) Curl Manual curl(1)

NAME

curl - transfer a URL

SYNOPSIS

curl [options] [URL...]

DESCRIPTION

curl is a tool to transfer data from or to a server, using one of the supported protocols (DICT, FILE, FTP, FTPS, GOPHER, HTTP, HTTPS,

IMAP, IMAPS, LDAP, LDAPS, POP3, POP3S, RTMP, RTSP, SCP, SFTP, SMB, SMBS, SMTP, SMTPS, TELNET, and TFTP). The command is designed to work without user interaction.

curl offers a busload of useful tricks like proxy support, user authentication, FTP upload, HTTP post, SSL connections, cookies, file transfer resume, Metalink, and more. As we will see below, the number of features will make our head spin!

curl is powered by libcurl for all transfer-related features. See libcurl(3) for details.

Manual page curl(1) line 1 (press h for help or q to quit)

After looking at some examples, we can also quickly look at the optional parameters without browsing through the complete documentation. We have several ways to do that.

Syntax:

root@htb[/htb]$ <tool> --help

Example:

root@htb[/htb]$ curl --help

Usage: curl [options...] <url>

--abstract-unix-socket <path> Connect via abstract Unix domain socket

--anyauth Pick any authentication method

-a, --append Append to target file when uploading

--basic Use HTTP Basic Authentication

--cacert <file> CA certificate to verify peer against

--capath <dir> CA directory to verify peer against

-E, --cert <certificate[:password]> Client certificate file and password

<SNIP>

We can also use the short version of it:

Syntax:

root@htb[/htb]$ <tool> -h

Example:

root@htb[/htb]$ curl -h

Usage: curl [options...] <url>

--abstract-unix-socket <path> Connect via abstract Unix domain socket

--anyauth Pick any authentication method

-a, --append Append to target file when uploading

--basic Use HTTP Basic Authentication

--cacert <file> CA certificate to verify peer against

--capath <dir> CA directory to verify peer against

-E, --cert <certificate[:password]> Client certificate file and password

<SNIP>

As we can see, the results from each other do not differ in this example. Another tool that can be useful in the beginning is apropos. Each manual page has a short description available within it. This tool searches the descriptions for instances of a given keyword.

Syntax:

root@htb[/htb]$ apropos <keyword>

Example:

root@htb[/htb]$ apropos sudo

sudo (8) - execute a command as another user

sudo.conf (5) - configuration for sudo front end

sudo_plugin (8) - Sudo Plugin API

sudo_root (8) - How to run administrative commands

sudoedit (8) - execute a command as another user

sudoers (5) - default sudo security policy plugin

sudoreplay (8) - replay sudo session logs

visudo (8) - edit the sudoers file

Another useful resource to get help if we have issues to understand a long command is: https://explainshell.com/\

Since we will be working with many different Linux systems, we need to learn the structure and the information about the system, its processes, network configurations, users, directories, user settings, and the corresponding parameters. Here is a list of the necessary tools that will help us get the above information. Most of them are installed by default.

| Command | Description |

whoami | Displays current username. |

id | Returns users identity |

hostname | Sets or prints the name of current host system. |

uname | Prints basic information about the operating system name and system hardware. |

pwd | Returns working directory name. |

ifconfig | The ifconfig utility is used to assign or to view an address to a network interface and/or configure network interface parameters. |

ip | Ip is a utility to show or manipulate routing, network devices, interfaces and tunnels. |

netstat | Shows network status. |

ss | Another utility to investigate sockets. |

ps | Shows process status. |

who | Displays who is logged in. |

env | Prints environment or sets and executes command. |

lsblk | Lists block devices. |

lsusb | Lists USB devices |

lsof | Lists opened files. |

lspci | Lists PCI devices. |

Let us look at a few examples.

Hostname

The hostname command is pretty self-explanatory and will just print the name of the computer that we are logged into

root@htb[/htb]$ hostname

nixfund

Whoami

This quick and easy command can be used on both Windows and Linux systems to get our current username. During a security assessment, we obtain reverse shell access on a host, and one of the first bits of situational awareness we should do is figuring out what user we are running as. From there, we can figure out if the user has any special privileges/access.

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ whoami

cry0l1t3

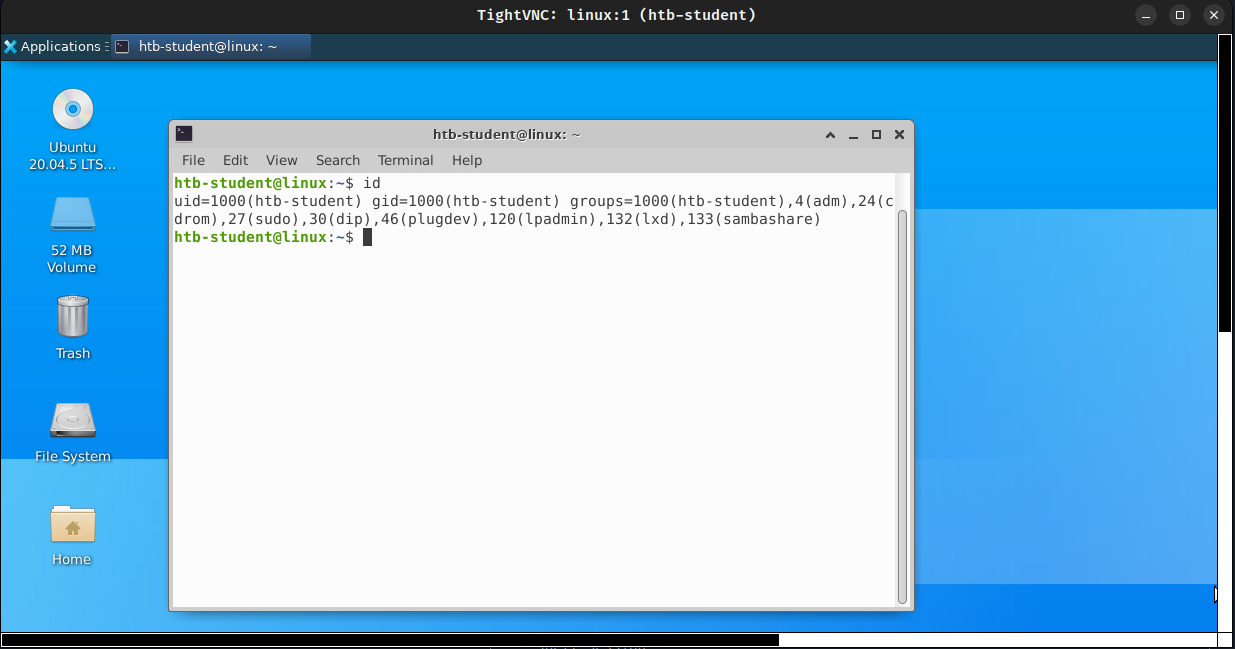

Id

The id command expands on the whoami command and prints out our effective group membership and IDs. This can be of interest to penetration testers looking to see what access a user may have and sysadmins looking to audit account permissions and group membership. In this output, the hackthebox group is of interest because it is non-standard, the adm group means that the user can read log files in /var/log and could potentially gain access to sensitive information, membership in the sudo group is of particular interest as this means our user can run some or all commands as the all-powerful root user. Sudo rights could help us escalate privileges or could be a sign to a sysadmin that they may need to audit permissions and group memberships to remove any access that is not required for a given user to carry out their day-to-day tasks.

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ id

uid=1000(cry0l1t3) gid=1000(cry0l1t3) groups=1000(cry0l1t3),1337(hackthebox),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),116(lpadmin),126(sambashare)

Uname

Let's dig into the uname command a bit more. If we type man uname in our terminal, we will bring up the man page for the command, which will show the possible options we can run with the command and the results

UNAME(1) User Commands UNAME(1)

NAME

uname - print system information

SYNOPSIS

uname [OPTION]...

DESCRIPTION

Print certain system information. With no OPTION, same as -s.

-a, --all

print all information, in the following order, except omit -p and -i if unknown:

-s, --kernel-name

print the kernel name

-n, --nodename

print the network node hostname

-r, --kernel-release

print the kernel release

-v, --kernel-version

print the kernel version

-m, --machine

print the machine hardware name

-p, --processor

print the processor type (non-portable)

-i, --hardware-platform

print the hardware platform (non-portable)

-o, --operating-system

Running uname -a will print all information about the machine in a specific order: kernel name, hostname, the kernel release, kernel version, machine hardware name, and operating system. The -a flag will omit -p (processor type) and -i (hardware platform) if they are unknown.

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ uname -a

Linux box 4.15.0-99-generic #100-Ubuntu SMP Wed Apr 22 20:32:56 UTC 2020 x86_64 x86_64 x86_64 GNU/Linux

From the above command, we can see that the kernel name is Linux, the hostname is box, the kernel release is 4.15.0-99-generic, the kernel version is #100-Ubuntu SMP Wed Apr 22 20:32:56 UTC 2020, and so on. Running any of these options on their own will give us the specific bit output we are interested in.

Uname to Obtain Kernel Release

Suppose we want to print out the kernel release to search for potential kernel exploits quickly. We can type uname -r to obtain this information.

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ uname -r

4.15.0-99-generic

With this info, we could go and search for "4.15.0-99-generic exploit," and the first result immediately appears useful to us.

It is highly recommended to study the commands and understand what they are for and what information they can provide. Though a bit tedious, we can learn much from studying the manpages for common commands. We may even find out things that we did not even know were possible with a given command. This information is not only used for working with Linux. However, it will also be used later to discover vulnerabilities and misconfigurations on the Linux system that may contribute to privilege escalation. Here are a few optional exercises that we can solve for practice purposes, which will help us become familiar with some of the commands.

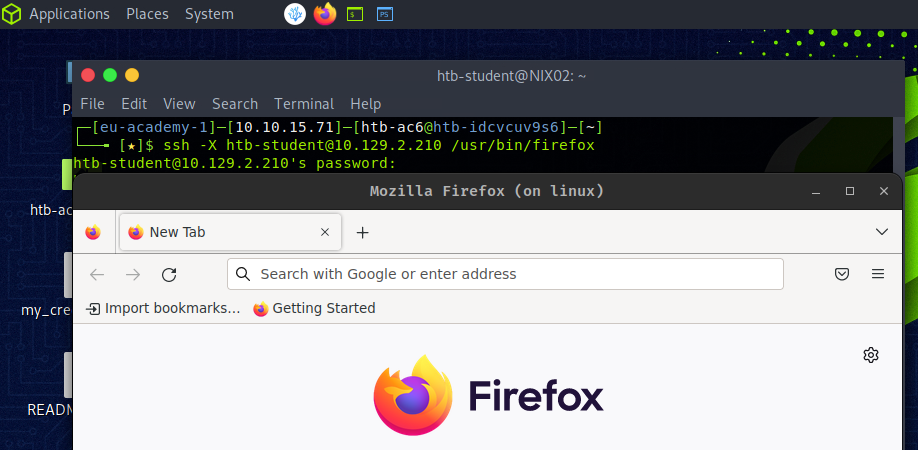

Secure Shell (SSH) refers to a protocol that allows clients to access and execute commands or actions on remote computers. On Linux-based hosts and servers running or another Unix-like operating system, SSH is one of the permanently installed standard tools and is the preferred choice for many administrators to configure and maintain a computer through remote access. It is an older and very proven protocol that does not require or offer a graphical user interface (GUI). For this reason, it works very efficiently and occupies very few resources. We use this type of connection in the following sections and in most of the other modules to offer the possibility to try out the learned commands and actions in a safe environment. We can connect to our targets with the following command:

root@htb[/htb]$ ssh [username]@[IP address]

Navigation is essential, like working with the mouse as a standard Windows user. With it, we move across the system and work in directories and with files, we need and want. Therefore, we use different commands and tools to print out information about a directory or a file and can use advanced options to optimize the output to our needs.

One of the best ways to learn something new is to experiment with it. Here we cover the sections on navigating through Linux, creating, moving, editing, and deleting files and folders, finding them on the operating system, different types of redirects, and what file descriptors are. We will also find shortcuts to make our work with the shell much easier and more comfortable. We recommend experimenting on our locally hosted VM. Ensure we have created a snapshot for our VM in case our system gets unexpectedly damaged.

Let us start with the navigation. Before we move through the system, we have to find out in which directory we are. We can find out where we are with the command pwd.

cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ pwd

/home/cry0l1t3

Only the ls command is needed to list all the contents inside a directory. It has many additional options that can complement the display of the content in the current folder.

cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ ls

Desktop Documents Downloads Music Pictures Public Templates Videos

Using it without any additional options will display the directories and files only. However, we can also add the -l option to display more information on those directories and files.

cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ ls -l

total 32

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:37 Desktop

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Documents

drwxr-xr-x 3 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 15 03:26 Downloads

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Music

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Pictures

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Public

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Templates

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Videos

First, we see the total amount of blocks (512-byte) used by the files and directories listed in the current directory, which indicates the total size used. That means it used 32 * 512-byte = 16384 bytes of disk space. Next, we see a few columns that are structured as follows:

| Column Content | Description |

drwxr-xr-x | Type and permissions |

2 | Number of hard links to the file/directory |

cry0l1t3 | Owner of the file/directory |

htbacademy | Group owner of the file/directory |

4096 | Size of the file or the number of blocks used to store the directory information |

Nov 13 17:37 | Date and time |

Desktop | Directory name |

However, we will not see everything that is in this folder. A directory can also have hidden files that start with a dot at the beginning of its name (e.g., .bashrc or .bash_history). Therefore, we need to use the command ls -la to list all files of a directory:

cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ ls -la

total 403188

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:37 .bash_history

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:37 .bashrc

...SNIP...

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:37 Desktop

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Documents

drwxr-xr-x 3 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 15 03:26 Downloads

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Music

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Pictures

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Public

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Templates

drwxr-xr-x 2 cry0l1t3 htbacademy 4096 Nov 13 17:34 Videos

To list the contents of a directory, we do not necessarily need to navigate there first. We can also use “ls” to specify the path where we want to know the contents.

cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ ls -l /var/

total 52

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Mai 15 18:54 backups

drwxr-xr-x 18 root root 4096 Nov 15 16:55 cache

drwxrwsrwt 2 root whoopsie 4096 Jul 25 2018 crash

drwxr-xr-x 66 root root 4096 Mai 15 03:08 lib

drwxrwsr-x 2 root staff 4096 Nov 24 2018 local

<SNIP>

We can do the same thing to navigate to the directory. To move through the directories, we use the command cd. Let us change to the /dev/shm directory. Of course, we can go to the /dev directory first and then /shm. Nevertheless, we can also enter the full path and jump there.

cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ cd /dev/shm

cry0l1t3@htb[/dev/shm]$

Since we were in the home directory before, we can quickly jump back to the directory we were last in.

cry0l1t3@htb[/dev/shm]$ cd -

cry0l1t3@htb[~]$

The shell also offers us the auto-complete function, which makes navigation easier. If we now type cd /dev/s and press [TAB] twice, we will get all entries starting with the letter “s” in the directory of /dev/.

cry0l1t3@htb[~]$ cd /dev/s [TAB 2x]

shm/ snd/

If we add the letter “h” to the letter “s,” the shell will complete the input since otherwise there will be no folders in this directory beginning with the letters “sh”. If we now display all contents of the directory, we will only see the following contents.

cry0l1t3@htb[/dev/shm]$ ls -la /dev/shm

total 0

drwxrwxrwt 2 root root 40 Mai 15 18:31 .

drwxr-xr-x 17 root root 4000 Mai 14 20:45 ..

The first entry with a single dot (.) indicates the current directory we are currently in. The second entry with two dots (..) represents the parent directory /dev. This means we can jump to the parent directory with the following command.

cry0l1t3@htb[/dev/shm]$ cd ..

cry0l1t3@htb[/dev]$

Since our shell is filled with some records, we can clean the shell with the command clear. First, however, let us return to the directory /dev/shm before and then execute the clear command to clean up our terminal.

cry0l1t3@htb[/dev]$ cd shm && clear

Another way to clean up our terminal is to use the shortcut [Ctrl] + [L]. We can also use the arrow keys (↑ or ↓) to scroll through the command history, which will show us the commands that we have used before. But we also can search through the command history using the shortcut [Ctrl] + [R] and type some of the text that we are looking for.

The main difference between working with files in Linux and Windows is the way we can access the files. For example, we usually have to open Explorer to find and edit files in Windows. In Linux, on the other hand, we have a terminal where we can access and edit files using commands. Moreover, we can even edit the files interactively without using an editor, such as vim or nano.

The terminal in Linux is a more efficient and faster tool because you can access the files directly with a few commands and edit and modify them selectively with regular expressions (regex). You can also run several commands simultaneously and redirect the output to a file. This saves time and is very handy when we want to edit many files at once.

Next, let us work with files and directories and learn how to create, rename, move, copy, and delete. First, let us create an empty file and a directory. We can use touch to create an empty file and mkdir to create a directory.

The syntax for this is the following:

Syntax - touch

root@htb[/htb]$ touch <name>

Syntax - mkdir

root@htb[/htb]$ mkdir <name>

In this example, we name the file info.txt and the directory Storage. To create these, we follow the commands and their syntax shown above.

Create an Empty File

root@htb[/htb]$ touch info.txt

Create a Directory

root@htb[/htb]$ mkdir Storage

We may want to have specific directories in the directory, and it would be very time-consuming to create this command for every single directory. The command mkdir has an option marked -p to add parent directories.

root@htb[/htb]$ mkdir -p Storage/local/user/documents

We can look at the whole structure after creating the parent directories with the tool tree.

root@htb[/htb]$ tree .

.

├── info.txt

└── Storage

└── local

└── user

└── documents

4 directories, 1 file

We can also create files directly in the directories by specifying the path where the file should be stored. The trick is to use the single dot (.) to tell the system that we want to start from the current directory. So the command for creating another empty file looks like this:

Create userinfo.txt

root@htb[/htb]$ touch ./Storage/local/user/userinfo.txt

root@htb[/htb]$ tree .

.

├── info.txt

└── Storage

└── local

└── user

├── documents

└── userinfo.txt

4 directories, 2 files

With the command mv, we can move and also rename files and directories. The syntax for this looks like this:

Syntax - mv

root@htb[/htb]$ mv <file/directory> <renamed file/directory>

First, let us rename the file info.txt to information.txt and then move it to the directory Storage.

Rename File

root@htb[/htb]$ mv info.txt information.txt

Now let us create a file named readme.txt in the current directory and then copy the files information.txt and readme.txt into the Storage/ directory.

Create readme.txt

root@htb[/htb]$ touch readme.txt

Move Files to Specific Directory

root@htb[/htb]$ mv information.txt readme.txt Storage/

root@htb[/htb]$ tree .

.

└── Storage

├── information.txt

├── local

│ └── user

│ ├── documents

│ └── userinfo.txt

└── readme.txt

4 directories, 3 files

Let us assume we want to have the readme.txt in the local/ directory. Then we can copy them there with the paths specified.

Copy readme.txt

root@htb[/htb]$ cp Storage/readme.txt Storage/local/

Now we can check if the file is thereby using the tool tree again.

root@htb[/htb]$ tree .

.

└── Storage

├── information.txt

├── local

│ ├── readme.txt

│ └── user

│ ├── documents

│ └── userinfo.txt

└── readme.txt

4 directories, 4 files

\

There are several ways to edit a file. One of the most common text editors for this is Vi and Vim. More rarely, there is the Nano editor. We will first deal with the Nano editor here, as it is a bit easier to understand. We can create a new file directly with the Nano editor by specifying the file's name directly as the first parameter. In this case, we create a new file named notes.txt.

root@htb[/htb]$ nano notes.txt

Now we should see a so-called "pager" open, and we can freely enter or insert any text. Our shell should then look something like this.

Nano Editor

GNU nano 2.9.3 notes.txt

Here we can type everything we want and make our notes.▓

^G Get Help ^O Write Out ^W Where Is ^K Cut Text ^J Justify ^C Cur Pos M-U Undo

^X Exit ^R Read File ^\ Replace ^U Uncut Text ^T To Spell ^_ Go To Line M-E Redo

Below we see two lines with short descriptions. The caret (^) stands for our "[CTRL]" key. For example, if we press [CTRL + W], a "Search:" line appears at the bottom of the editor, where we can enter the word or words we are looking for. If we now search for the word "we" and press [ENTER], the cursor will move to the first word that matches.

GNU nano 2.9.3 notes.txt

Here ▓we can type everything we want and make our notes.

Search: notes

^G Get Help M-C Case Sens M-B Backwards M-J FullJstify ^W Beg of Par ^Y First Line ^P PrevHstory

^C Cancel M-R Regexp ^R Replace ^T Go To Line ^O End of Par ^V Last Line ^N NextHstory

To jump to the next match with the cursor, we press [CTRL + W] again and confirm with [ENTER] without any additional information.

GNU nano 2.9.3 notes.txt

Here we can type everything ▓we want and make our notes.

Search [we]:

^G Get Help M-C Case Sens M-B Backwards M-J FullJstify ^W Beg of Par ^Y First Line ^P PrevHstory

^C Cancel M-R Regexp ^R Replace ^T Go To Line ^O End of Par ^V Last Line ^N NextHstory

Now we can save the file by pressing [CTRL + O] and confirm the file name with [ENTER].

GNU nano 2.9.3 notes.txt

Here we can type everything we want and make our notes.

File Name to Write: notes.txt▓

^G Get Help M-C Case Sens M-B Backwards M-J FullJstify ^W Beg of Par ^Y First Line ^P PrevHstory

^C Cancel M-R Regexp ^R Replace ^T Go To Line ^O End of Par ^V Last Line ^N NextHstory

After we have saved the file, we can leave the editor with [CTRL + X].

Back on the Shell

To view the contents of the file, we can use the command cat.

root@htb[/htb]$ cat notes.txt

Here we can type everything we want and make our notes.

There are many files on Linux systems that can play an essential role for us as penetration testers whose rights have not been correctly set by the administrators. Such files may include the file "/etc/passwd".

Vim is an open-source editor for all kinds of ASCII text, just like Nano. It is an improved clone of the previous Vi. It is an extremely powerful editor that focuses on the essentials, namely editing text. For tasks that go beyond that, Vim provides an interface to external programs, such as grep, awk, sed, etc., which can handle their specific tasks much better than a corresponding function directly implemented in an editor usually can. This makes the editor small and compact, fast, powerful, flexible, and less error-prone.

Vim follows the Unix principle here: many small specialized programs that are well tested and proven, when combined and communicating with each other, resulting in a flexible and powerful system.

Vim

root@htb[/htb]$ vim

1 $

~

~ VIM - Vi IMproved

~

~ version 8.0.1453

~ by Bram Moolenaar et al.

~ Modified by pkg-vim-maintainers@lists.alioth.debian.org

~ Vim is open source and freely distributable

~

~ Sponsor Vim development!

~ type :help sponsor<Enter> for information

~

~ type :q<Enter> to exit

~ type :help<Enter> or <F1> for on-line help

~ type :help version8<Enter> for version info

~

0,0-1 All

In contrast to Nano, Vim is a modal editor that can distinguish between text and command input. Vim offers a total of six fundamental modes that make our work easier and make this editor so powerful:

| Mode | Description |

Normal | In normal mode, all inputs are considered as editor commands. So there is no insertion of the entered characters into the editor buffer, as is the case with most other editors. After starting the editor, we are usually in the normal mode. |

Insert | With a few exceptions, all entered characters are inserted into the buffer. |

Visual | The visual mode is used to mark a contiguous part of the text, which will be visually highlighted. By positioning the cursor, we change the selected area. The highlighted area can then be edited in various ways, such as deleting, copying, or replacing it. |

Command | It allows us to enter single-line commands at the bottom of the editor. This can be used for sorting, replacing text sections, or deleting them, for example. |

Replace | In replace mode, the newly entered text will overwrite existing text characters unless there are no more old characters at the current cursor position. Then the newly entered text will be added. |

When we have the Vim editor open, we can go into command mode by typing ":" and then typing "q" to close Vim.

1 $

~

~ VIM - Vi IMproved

~

~ version 8.0.1453

~ by Bram Moolenaar et al.

~ Modified by pkg-vim-maintainers@lists.alioth.debian.org

~ Vim is open source and freely distributable

~

~ Sponsor Vim development!

~ type :help sponsor<Enter> for information

~

~ type :q<Enter> to exit

~ type :help<Enter> or <F1> for on-line help

~ type :help version8<Enter> for version info

~

:q▓

Vim offers an excellent opportunity called vimtutor to practice and get familiar with the editor. It may seem very difficult and complicated at first, but it will only feel that way for a short time. The efficiency we gain from Vim once we get used to it is enormous. Entering the tutor mode can be done using the Command mode :Tutor.

VimTutor

root@htb[/htb]$ vimtutor

===============================================================================

= W e l c o m e t o t h e V I M T u t o r - Version 1.7 =

===============================================================================

Vim is a very powerful editor that has many commands, too many to

explain in a tutor such as this. This tutor is designed to describe

enough of the commands that you will be able to easily use Vim as

an all-purpose editor.

The approximate time required to complete the tutor is 25-30 minutes,

depending upon how much time is spent with experimentation.

ATTENTION:

The commands in the lessons will modify the text. Make a copy of this

file to practice on (if you started "vimtutor" this is already a copy).

It is important to remember that this tutor is set up to teach by

use. That means that you need to execute the commands to learn them

properly. If you only read the text, you will forget the commands!

Now, make sure that your Caps-Lock key is NOT depressed and press

the j key enough times to move the cursor so that lesson 1.1

completely fills the screen.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

It is crucial to be able to find the files and folders we need. Once we have gained access to a Linux based system, it will be essential to find configuration files, scripts created by users or the administrator, and other files and folders. We do not have to manually browse through every single folder and check when modified for the last time. There are some tools we can use to make this work easier.

One of the common tools is which. This tool returns the path to the file or link that should be executed. This allows us to determine if specific programs, like cURL, netcat, wget, python, gcc, are available on the operating system. Let us use it to search for Python in our interactive instance.

root@htb[/htb]$ which python

/usr/bin/python

If the program we search for does not exist, no results will be displayed.

Another handy tool is find. Besides the function to find files and folders, this tool also contains the function to filter the results. We can use filter parameters like the size of the file or the date. We can also specify if we only search for files or folders.

Syntax - find

root@htb[/htb]$ find <location> <options>

Let us look at an example of what such a command with multiple options would look like.

root@htb[/htb]$ find / -type f -name *.conf -user root -size +20k -newermt 2020-03-03 -exec ls -al {} \; 2>/dev/null

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 136392 Apr 25 20:29 /usr/src/linux-headers-5.5.0-1parrot1-amd64/include/config/auto.conf

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 82290 Apr 25 20:29 /usr/src/linux-headers-5.5.0-1parrot1-amd64/include/config/tristate.conf

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 95813 May 7 14:33 /usr/share/metasploit-framework/data/jtr/repeats32.conf

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 60346 May 7 14:33 /usr/share/metasploit-framework/data/jtr/dynamic.conf

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 96249 May 7 14:33 /usr/share/metasploit-framework/data/jtr/dumb32.conf

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 54755 May 7 14:33 /usr/share/metasploit-framework/data/jtr/repeats16.conf

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 22635 May 7 14:33 /usr/share/metasploit-framework/data/jtr/korelogic.conf

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 108534 May 7 14:33 /usr/share/metasploit-framework/data/jtr/john.conf

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 55285 May 7 14:33 /usr/share/metasploit-framework/data/jtr/dumb16.conf

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 21254 May 2 11:59 /usr/share/doc/sqlmap/examples/sqlmap.conf

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 25086 Mar 4 22:04 /etc/dnsmasq.conf

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 21254 May 2 11:59 /etc/sqlmap/sqlmap.conf

Now let us take a closer look at the options we used in the previous command. If we hover the mouse over the respective options, a small window will appear with an explanation. These explanations will also be found in other modules, which should help us if we are not yet familiar with one of the tools.

| Option | Description |

-type f | Hereby, we define the type of the searched object. In this case, 'f' stands for 'file'. |

-name .conf | With '-name', we indicate the name of the file we are looking for. The asterisk (.conf' extension. |

-user root | This option filters all files whose owner is the root user. |

-size +20k | We can then filter all the located files and specify that we only want to see the files that are larger than 20 KiB. |

-newermt 2020-03-03 | With this option, we set the date. Only files newer than the specified date will be presented. |

-exec ls -al {} \; | This option executes the specified command, using the curly brackets as placeholders for each result. The backslash escapes the next character from being interpreted by the shell because otherwise, the semicolon would terminate the command and not reach the redirection. |

2>/dev/null | This is a STDERR redirection to the 'null device', which we will come back to in the next section. This redirection ensures that no errors are displayed in the terminal. This redirection must not be an option of the 'find' command. |

It will take much time to search through the whole system for our files and directories to perform many different searches. The command locate offers us a quicker way to search through the system. In contrast to the find command, locate works with a local database that contains all information about existing files and folders. We can update this database with the following command.

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo updatedb

If we now search for all files with the ".conf" extension, you will find that this search produces results much faster than using find.

Find Files and Directories

root@htb[/htb]$ locate *.conf

/etc/GeoIP.conf

/etc/NetworkManager/NetworkManager.conf

/etc/UPower/UPower.conf

/etc/adduser.conf

<SNIP>

However, this tool does not have as many filter options that we can use. So it is always worth considering whether we can use the locate command or instead use the find command. It always depends on what we are looking for.

A file descriptor (FD) in Unix/Linux operating systems is an indicator of connection maintained by the kernel to perform Input/Output (I/O) operations. In Windows-based operating systems, it is called filehandle. It is the connection (generally to a file) from the Operating system to perform I/O operations (Input/Output of Bytes). By default, the first three file descriptors in Linux are:

STDIN – 0STDOUT – 1STDERR – 2STDIN and STDOUT

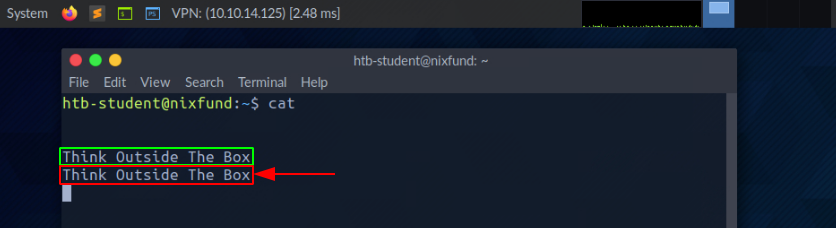

Let us see an example with cat. When running cat, we give the running program our standard input (STDIN - FD 0), marked green, wherein this case "SOME INPUT" is. As soon as we have confirmed our input with [ENTER], it is returned to the terminal as standard output (STDOUT - FD 1), marked red.

STDOUT and STDERR

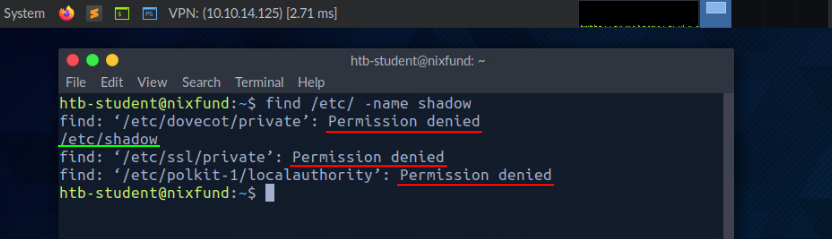

In the next example, by using the find command, we will see the standard output (STDOUT - FD 1) marked in green and standard error (STDERR - FD 2) marked in red.

root@htb[/htb]$ find /etc/ -name shadow

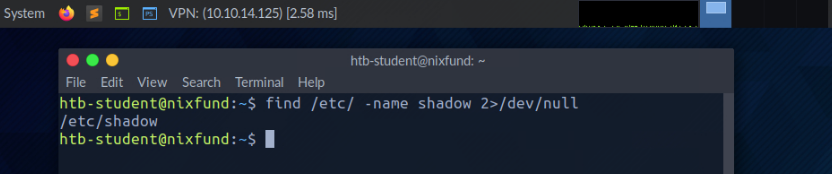

In this case, the error is marked and displayed with "Permission denied". We can check this by redirecting the file descriptor for the errors (FD 2 - STDERR) to "/dev/null." This way, we redirect the resulting errors to the "null device," which discards all data.

root@htb[/htb]$ find /etc/ -name shadow 2>/dev/null

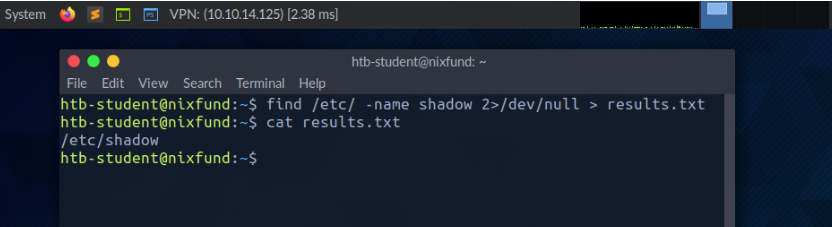

Redirect STDOUT to a File

Now we can see that all errors (STDERR) previously presented with "Permission denied" are no longer displayed. The only result we see now is the standard output (STDOUT), which we can also redirect to a file with the name results.txt that will only contain standard output without the standard errors.

root@htb[/htb]$ find /etc/ -name shadow 2>/dev/null > results.txt

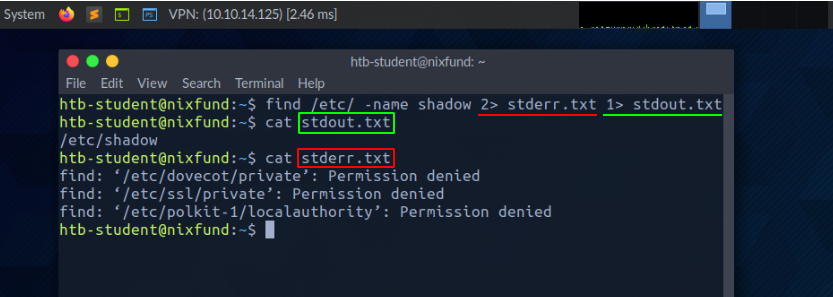

Redirect STDOUT and STDERR to Separate Files

We should have noticed that we did not use a number before the greater-than sign (>) in the last example. That is because we redirected all the standard errors to the "null device" before, and the only output we get is the standard output (FD 1 - STDOUT). To make this more precise, we will redirect standard error (FD 2 - STDERR) and standard output (FD 1 - STDOUT) to different files.

root@htb[/htb]$ find /etc/ -name shadow 2> stderr.txt 1> stdout.txt

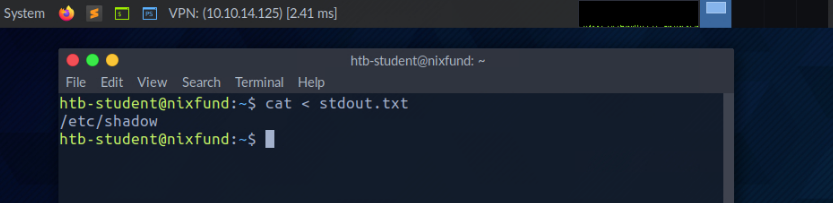

Redirect STDIN

As we have already seen, in combination with the file descriptors, we can redirect errors and output with greater-than character (>). This also works with the lower-than sign (<). However, the lower-than sign serves as standard input (FD 0 - STDIN). These characters can be seen as "direction" in the form of an arrow that tells us "from where" and "where to" the data should be redirected. We use the cat command to use the contents of the file "stdout.txt" as STDIN.

root@htb[/htb]$ cat < stdout.txt

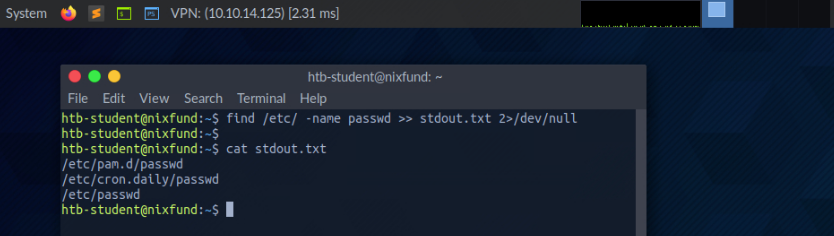

Redirect STDOUT and Append to a File

When we use the greater-than sign (>) to redirect our STDOUT, a new file is automatically created if it does not already exist. If this file exists, it will be overwritten without asking for confirmation. If we want to append STDOUT to our existing file, we can use the double greater-than sign (>>).

root@htb[/htb]$ find /etc/ -name passwd >> stdout.txt 2>/dev/null

Redirect STDIN Stream to a File

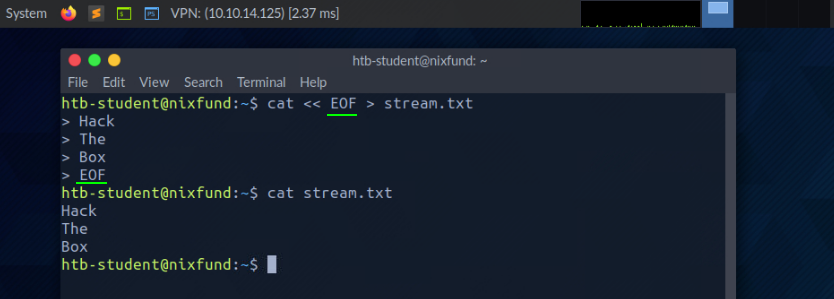

We can also use the double lower-than characters (<<) to add our standard input through a stream. We can use the so-called End-Of-File (EOF) function of a Linux system file, which defines the input's end. In the next example, we will use the cat command to read our streaming input through the stream and direct it to a file called "stream.txt."

root@htb[/htb]$ cat << EOF > stream.txt

Pipes

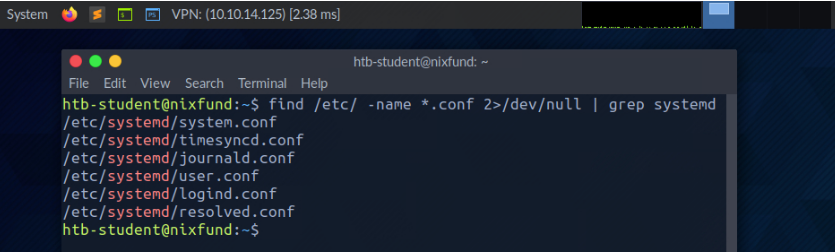

Another way to redirect STDOUT is to use pipes (|). These are useful when we want to use the STDOUT from one program to be processed by another. One of the most commonly used tools is grep, which we will use in the next example. Grep is used to filter STDOUT according to the pattern we define. In the next example, we use the find command to search for all files in the "/etc/" directory with a ".conf" extension. Any errors are redirected to the "null device" (/dev/null). Using grep, we filter out the results and specify that only the lines containing the pattern "systemd" should be displayed.

root@htb[/htb]$ find /etc/ -name *.conf 2>/dev/null | grep systemd

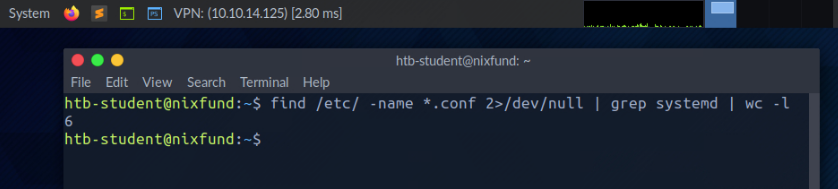

The redirections work, not only once. We can use the obtained results to redirect them to another program. For the next example, we will use the tool called wc, which should count the total number of obtained results.

root@htb[/htb]$ find /etc/ -name *.conf 2>/dev/null | grep systemd | wc -l

In the last section, we learned about the redirections we can use to redirect results from one program to another for processing. To read files, we do not necessarily have to use an editor for that. There are two tools called more and less, which are very identical. These are fundamental pagers that allow us to scroll through the file in an interactive view. Let us have a look at some examples.

root@htb[/htb]$ more /etc/passwd

After we read the content using cat and redirected it to more, the already mentioned pager opens, and we will automatically start at the beginning of the file.

Filter Contents

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

daemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/sbin:/usr/sbin/nologin

bin:x:2:2:bin:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologin

sys:x:3:3:sys:/dev:/usr/sbin/nologin

sync:x:4:65534:sync:/bin:/bin/sync

<SNIP>

--More--

With the [Q] key, we can leave this pager. We will notice that the output remains in the terminal.

If we now take a look at the tool less, we will notice on the man page that it contains many more features than more.

root@htb[/htb]$ less /etc/passwd

The presentation is almost the same as with more.

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

daemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/sbin:/usr/sbin/nologin

bin:x:2:2:bin:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologin

sys:x:3:3:sys:/dev:/usr/sbin/nologin

sync:x:4:65534:sync:/bin:/bin/sync

<SNIP>

:

When closing less with the [Q] key, we will notice that the output we have seen, unlike more, does not remain in the terminal.

Sometimes we will only be interested in specific issues either at the beginning of the file or the end. If we only want to get the first lines of the file, we can use the tool head. By default, head prints the first ten lines of the given file or input, if not specified otherwise.

root@htb[/htb]$ head /etc/passwd

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

daemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/sbin:/usr/sbin/nologin

bin:x:2:2:bin:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologin

sys:x:3:3:sys:/dev:/usr/sbin/nologin

sync:x:4:65534:sync:/bin:/bin/sync

games:x:5:60:games:/usr/games:/usr/sbin/nologin

man:x:6:12:man:/var/cache/man:/usr/sbin/nologin

lp:x:7:7:lp:/var/spool/lpd:/usr/sbin/nologin

mail:x:8:8:mail:/var/mail:/usr/sbin/nologin

news:x:9:9:news:/var/spool/news:/usr/sbin/nologin

If we only want to see the last parts of a file or results, we can use the counterpart of head called tail, which returns the last ten lines.

root@htb[/htb]$ tail /etc/passwd

miredo:x:115:65534::/var/run/miredo:/usr/sbin/nologin

usbmux:x:116:46:usbmux daemon,,,:/var/lib/usbmux:/usr/sbin/nologin

rtkit:x:117:119:RealtimeKit,,,:/proc:/usr/sbin/nologin

nm-openvpn:x:118:120:NetworkManager OpenVPN,,,:/var/lib/openvpn/chroot:/usr/sbin/nologin

nm-openconnect:x:119:121:NetworkManager OpenConnect plugin,,,:/var/lib/NetworkManager:/usr/sbin/nologin

pulse:x:120:122:PulseAudio daemon,,,:/var/run/pulse:/usr/sbin/nologin

beef-xss:x:121:124::/var/lib/beef-xss:/usr/sbin/nologin

lightdm:x:122:125:Light Display Manager:/var/lib/lightdm:/bin/false

do-agent:x:998:998::/home/do-agent:/bin/false

user6:x:1000:1000:,,,:/home/user6:/bin/bash

Depending on which results and files are dealt with, they are rarely sorted. Often it is necessary to sort the desired results alphabetically or numerically to get a better overview. For this, we can use a tool called sort.

root@htb[/htb]$ cat /etc/passwd | sort

_apt:x:104:65534::/nonexistent:/usr/sbin/nologin

backup:x:34:34:backup:/var/backups:/usr/sbin/nologin

bin:x:2:2:bin:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologin

cry0l1t3:x:1001:1001::/home/cry0l1t3:/bin/bash

daemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/sbin:/usr/sbin/nologin

dnsmasq:x:107:65534:dnsmasq,,,:/var/lib/misc:/usr/sbin/nologin

dovecot:x:114:117:Dovecot mail server,,,:/usr/lib/dovecot:/usr/sbin/nologin

dovenull:x:115:118:Dovecot login user,,,:/nonexistent:/usr/sbin/nologin

ftp:x:113:65534::/srv/ftp:/usr/sbin/nologin

games:x:5:60:games:/usr/games:/usr/sbin/nologin

gnats:x:41:41:Gnats Bug-Reporting System (admin):/var/lib/gnats:/usr/sbin/nologin

htb-student:x:1002:1002::/home/htb-student:/bin/bash

<SNIP>

As we can see now, the output no longer starts with root but is now sorted alphabetically.

More often, we will only search for specific results that contain patterns we have defined. One of the most used tools for this is grep, which offers many different features. Accordingly, we can search for users who have the default shell "/bin/bash" set as an example.

root@htb[/htb]$ cat /etc/passwd | grep "/bin/bash"

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

mrb3n:x:1000:1000:mrb3n:/home/mrb3n:/bin/bash

cry0l1t3:x:1001:1001::/home/cry0l1t3:/bin/bash

htb-student:x:1002:1002::/home/htb-student:/bin/bash

Another possibility is to exclude specific results. For this, the option "-v" is used with grep. In the next example, we exclude all users who have disabled the standard shell with the name "/bin/false" or "/usr/bin/nologin".

root@htb[/htb]$ cat /etc/passwd | grep -v "false\|nologin"

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

sync:x:4:65534:sync:/bin:/bin/sync

postgres:x:111:117:PostgreSQL administrator,,,:/var/lib/postgresql:/bin/bash

user6:x:1000:1000:,,,:/home/user6:/bin/bash

Specific results with different characters may be separated as delimiters. Here it is handy to know how to remove specific delimiters and show the words on a line in a specified position. One of the tools that can be used for this is cut. Therefore we use the option "-d" and set the delimiter to the colon character (:) and define with the option "-f" the position in the line we want to output.

Filter Contents

root@htb[/htb]$ cat /etc/passwd | grep -v "false\|nologin" | cut -d":" -f1

root

sync

mrb3n

cry0l1t3

htb-student

Another possibility to replace certain characters from a line with characters defined by us is the tool tr. As the first option, we define which character we want to replace, and as a second option, we define the character we want to replace it with. In the next example, we replace the colon character with space.

root@htb[/htb]$ cat /etc/passwd | grep -v "false\|nologin" | tr ":" " "

root x 0 0 root /root /bin/bash

sync x 4 65534 sync /bin /bin/sync

mrb3n x 1000 1000 mrb3n /home/mrb3n /bin/bash

cry0l1t3 x 1001 1001 /home/cry0l1t3 /bin/bash

htb-student x 1002 1002 /home/htb-student /bin/bash

Since search results can often have an unclear representation, the tool column is well suited to display such results in tabular form using the "-t."

root@htb[/htb]$ cat /etc/passwd | grep -v "false\|nologin" | tr ":" " " | column -t

root x 0 0 root /root /bin/bash

sync x 4 65534 sync /bin /bin/sync

mrb3n x 1000 1000 mrb3n /home/mrb3n /bin/bash

cry0l1t3 x 1001 1001 /home/cry0l1t3 /bin/bash

htb-student x 1002 1002 /home/htb-student /bin/bash

As we may have noticed, the user "postgres" has one row too many. To keep it as simple as possible to sort out such results, the (g)awk programming is beneficial, which allows us to display the first ($1) and last ($NF) result of the line.

root@htb[/htb]$ cat /etc/passwd | grep -v "false\|nologin" | tr ":" " " | awk '{print $1, $NF}'

root /bin/bash

sync /bin/sync

mrb3n /bin/bash

cry0l1t3 /bin/bash

htb-student /bin/bash

There will come moments when we want to change specific names in the whole file or standard input. One of the tools we can use for this is the stream editor called sed. One of the most common uses of this is substituting text. Here, sed looks for patterns we have defined in the form of regular expressions (regex) and replaces them with another pattern that we have also defined. Let us stick to the last results and say we want to replace the word "bin" with "HTB."

The "s" flag at the beginning stands for the substitute command. Then we specify the pattern we want to replace. After the slash (/), we enter the pattern we want to use as a replacement in the third position. Finally, we use the "g" flag, which stands for replacing all matches.

root@htb[/htb]$ cat /etc/passwd | grep -v "false\|nologin" | tr ":" " " | awk '{print $1, $NF}' | sed 's/bin/HTB/g'

root /HTB/bash

sync /HTB/sync

mrb3n /HTB/bash

cry0l1t3 /HTB/bash

htb-student /HTB/bash

Last but not least, it will often be useful to know how many successful matches we have. To avoid counting the lines or characters manually, we can use the tool wc. With the "-l" option, we specify that only the lines are counted.

root@htb[/htb]$ cat /etc/passwd | grep -v "false\|nologin" | tr ":" " " | awk '{print $1, $NF}' | wc -l

5

It may be a bit overwhelming at first to deal with so many different tools and their functions if we are not familiar with them. Take your time and experiment with the tools. Have a look at the man pages (man <tool>) or call the help for it (<tool> -h / <tool> --help). The best way to become familiar with all the tools is to practice. Try to use them as often as possible, and we will be able to filter many things intuitively after a short time.

Here are a few optional exercises we can use to improve our filtering skills and get more familiar with the terminal and the commands. The file we will need to work with is the /etc/passwd file on our target and we can use any shown command above. Our goal is to filter and display only specific contents. Read the file and filter its contents in such a way that we see only:

| 1. | A line with the username cry0l1t3. |

| 2. | The usernames. |

| 3. | The username cry0l1t3 and his UID. |

| 4. | The username cry0l1t3 and his UID separated by a comma (,). |

| 5. | The username cry0l1t3, his UID, and the set shell separated by a comma (,). |

| 6. | All usernames with their UID and set shells separated by a comma (,). |

| 7. | All usernames with their UID and set shells separated by a comma (,) and exclude the ones that contain nologin or false. |

| 8. | All usernames with their UID and set shells separated by a comma (,) and exclude the ones that contain nologin and count all lines of the filtered output. |

Regular expressions (RegEx) are an art of expression language to search for patterns in text and files. They can be used to find and replace text, analyze data, validate input, perform searches, and more. In simple terms, they are a filter criterion that can be used to analyze and manipulate strings. They are available in various programming languages and programs and are used in many different ways and functions.

A regular expression is a sequence of letters and symbols that form a search pattern. In addition, regular expressions can be created with patterns called metacharacters. Meta characters are symbols that define the search pattern but have no literal meaning. We can use it in tools like grep or sed or others. Often regex is implemented in web applications for the validation of user input.

Among other things, regex offers us the possibility to group the desired search patterns. Basically, regex follows three different concepts, which are distinguished by the three different brackets:

| Operators | Description | |

| 1 | (a) | The round brackets are used to group parts of a regex. Within the brackets, you can define further patterns which should be processed together. |

| 2 | [a-z] | The square brackets are used to define character classes. Inside the brackets, you can specify a list of characters to search for. |

| 3 | {1,10} | The curly brackets are used to define quantifiers. Inside the brackets, you can specify a number or a range that indicates how often a previous pattern should be repeated. |

| 4 | | | Also called the OR operator and shows results when one of the two expressions matches |

| 5 | .* | Also called the AND operator and displayed results only if both expressions match |

Suppose we use the OR operator. The regex searches for one of the given search parameters. In the next example, we search for lines containing the word my or false. To use these operators, you need to apply the extended regex using the -E option in grep.

OR operator

cry0l1t3@htb:~$ grep -E "(my|false)" /etc/passwd

lxd:x:105:65534::/var/lib/lxd/:/bin/false

pollinate:x:109:1::/var/cache/pollinate:/bin/false

mysql:x:116:120:MySQL Server,,:/nonexistent:/bin/false

Since one of the two search parameters always occurs in the three lines, all three lines are displayed accordingly. However, if we use the AND operator, we will get a different result for the same search parameters.

AND operator

cry0l1t3@htb:~$ grep -E "(my.*false)" /etc/passwd

mysql:x:116:120:MySQL Server,,:/nonexistent:/bin/false

Basically, what we are saying with this command is that we are looking for a line where we want to see both my and false. A simplified example would also be to use grep twice and look like this:

cry0l1t3@htb:~$ grep -E "my" /etc/passwd | grep -E "false"

mysql:x:116:120:MySQL Server,,:/nonexistent:/bin/false

Here are some optional tasks to practice regex that can help us to handle it better and more efficiently. For all exercises, we will use the /etc/ssh/sshd_config file on our Pwnbox instance.

| 1 | Show all lines that do not contain the # character. |

| 2 | Search for all lines that contain a word that starts with Permit. |

| 3 | Search for all lines that contain a word ending with Authentication. |

| 4 | Search for all lines containing the word Key. |

| 5 | Search for all lines beginning with Password and containing yes. |

| 6 | Search for all lines that end with yes. |

Under Linux, permissions are assigned to users and groups. Each user can be a member of different groups, and membership in these groups gives the user specific, additional permissions. Each file and directory belongs to a specific user and a specific group. So the permissions for users and groups that defined a file are also defined for the respective owners. When we create new files or directories, they belong to the group we belong to and us.

When a user wants to access the contents of a Linux directory, they must first traverse the directory, which means navigating to that directory, requiring the user to have execute permissions on the directory. Without this permission, the user cannot access the directory's contents and will instead be presented with a “Permission Denied" error message.

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ ls -l

drw-rw-r-- 3 cry0l1t3 cry0l1t3 4096 Jan 12 12:30 scripts

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ ls -al mydirectory/

ls: cannot access 'mydirectory/script.sh': Permission denied

ls: cannot access 'mydirectory/..': Permission denied

ls: cannot access 'mydirectory/subdirectory': Permission denied

ls: cannot access 'mydirectory/.': Permission denied

total 0

d????????? ? ? ? ? ? .

d????????? ? ? ? ? ? ..

-????????? ? ? ? ? ? script.sh

d????????? ? ? ? ? ? subdirectory

It is important to note that execute permissions are necessary to traverse a directory, no matter the user's level of access. Also, execute permissions on a directory do not allow a user to execute or modify any files or contents within the directory, only to traverse and access the content of the directory.

To execute files within the directory, a user needs execute permissions on the corresponding file. To modify the contents of a directory (create, delete, or rename files and subdirectories), the user needs write permissions on the directory.

The whole permission system on Linux systems is based on the octal number system, and basically, there are three different types of permissions a file or directory can be assigned:

r) - Readw) - Writex) - ExecuteThe permissions can be set for the owner, group, and others like presented in the next example with their corresponding permissions.

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ ls -l /etc/passwd

- rwx rw- r-- 1 root root 1641 May 4 23:42 /etc/passwd

- --- --- --- | | | | |__________|

| | | | | | | | |_ Date

| | | | | | | |__________ File Size

| | | | | | |_______________ Group

| | | | | |____________________ User

| | | | |_______________________ Number of hard links

| | | |_ Permission of others (read)

| | |_____ Permissions of the group (read, write)

| |_________ Permissions of the owner (read, write, execute)

|____________ File type (- = File, d = Directory, l = Link, ... )

We can modify permissions using the chmod command, permission group references (u - owner, g - Group, o - others, a - All users), and either a [+] or a [-] to add remove the designated permissions. In the following example, a user creates a new shell script owned by that user, not executable, and set with read/write permissions for all users.

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ ls -l shell

-rwxr-x--x 1 cry0l1t3 htbteam 0 May 4 22:12 shell

We can then apply read permissions for all users and see the result.

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ chmod a+r shell && ls -l shell

-rwxr-xr-x 1 cry0l1t3 htbteam 0 May 4 22:12 shell

We can also set the permissions for all other users to read only using the octal value assignment.

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ chmod 754 shell && ls -l shell

-rwxr-xr-- 1 cry0l1t3 htbteam 0 May 4 22:12 shell

Let us look at all the representations associated with it to understand better how the permission assignment is calculated.

Binary Notation: 4 2 1 | 4 2 1 | 4 2 1

----------------------------------------------------------

Binary Representation: 1 1 1 | 1 0 1 | 1 0 0

----------------------------------------------------------

Octal Value: 7 | 5 | 4

----------------------------------------------------------

Permission Representation: r w x | r - x | r - -

If we sum the set bits from the Binary Representation assigned to the values from Binary Notation together, we get the Octal Value. The Permission Representation represents the bits set in the Binary Representation by using the three characters, which only recognizes the set permissions easier.

To change the owner and/or the group assignments of a file or directory, we can use the chown command. The syntax is like following:

Syntax - chown

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ chown <user>:<group> <file/directory>

In this example, "shell" can be replaced with any arbitrary file or folder.

cry0l1t3@htb[/htb]$ chown root:root shell && ls -l shell

-rwxr-xr-- 1 root root 0 May 4 22:12 shell

Besides assigning direct user and group permissions, we can also configure special permissions for files by setting the Set User ID (SUID) and Set Group ID (SGID) bits. These SUID/SGID bits allow, for example, users to run programs with the rights of another user. Administrators often use this to give their users special rights for certain applications or files. The letter "s" is used instead of an "x". When executing such a program, the SUID/SGID of the file owner is used.

It is often the case that administrators are not familiar with the applications but still assign the SUID/SGID bits, which leads to a high-security risk. Such programs may contain functions that allow the execution of a shell from the pager, such as the application "journalctl."