Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) represents a vital asset in our arsenal, providing essential insights to fortify our defenses against cyberattacks. The primary objective of our CTI team is to transition our defense strategies from merely reactive measures to a more proactive, anticipatory stance. They contribute crucial insights to our Security Operations Center (SOC).

Four fundamental principles make CTI an integral part of our cybersecurity strategy:

Relevance: The cyber world is awash with diverse sources of information, from social media posts and security vendor reports to shared insights from similar organizations. However, the true value of this information lies in its relevance to our organization. For instance, if there is a reported vulnerability in a software that we, or our trusted partner organizations, do not use, the urgency to implement defensive measures is naturally diminished.Timeliness: Swift communication of intelligence to our defense team is crucial for the implementation of effective mitigation measures. The value of information depreciates over time - freshly discovered data is more valuable, and 'aged' indicators lose their relevance as they might no longer be used by the adversary or may have been resolved by the affected organization.Actionability: Data under analysis by a CTI analyst should yield actionable insights for our defense team. If the intelligence doesn't offer clear directives for action, its value diminishes. Intelligence must be scrutinized until it yields relevant, timely, and actionable insights for our network defense. Unactionable intelligence can lead to a self-perpetuating cycle of non-productive analysis, often referred to as a "self-licking ice cream cone".Accuracy: Before disseminating any intelligence, it must be verified for accuracy. Incorrect indicators, misattributions, or flawed Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) can result in wastage of valuable time and resources. If the accuracy of any information is uncertain, it should be labeled with a confidence indicator, ensuring that our defense team is aware of potential inaccuracies.When these four factors synergize, the intelligence gleaned allows us to:

Threat Intelligence and Threat Hunting represent two distinct, yet intrinsically interconnected, specialties within the realm of cybersecurity. While they serve separate functions, they both contribute significantly to the development of a comprehensive security analyst. However, it's important to note that they are not substitutes for each other.

Threat Intelligence (Predictive): The primary aim here is to anticipate the adversary's moves, ascertain their targets, and discern their methods of information acquisition. The adversary has a specific objective, and as a team involved in Threat Intelligence, our mission is to predict:

Threat Hunting (Reactive and Proactive): Yes, the two terms are opposites, but they encapsulate the essence of Threat Hunting. An initiating event or incident, whether it occurs within our network or in a network of a similar industry, prompts our team to launch an operation to ascertain whether an adversary is present in the network, or if one was present and evaded detection.

Ultimately, Threat Intelligence and Threat Hunting bolster each other, strengthening our organization's overall network defense posture. As our Threat Intelligence team analyzes adversary activities and develops comprehensive adversary profiles, this information can be shared with our Threat Hunting analysts to inform their operations. Conversely, the findings from Threat Hunting operations can equip our Threat Intelligence analysts with additional data to refine their intelligence and enhance the accuracy of their predictions.

What truly makes Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) valuable? What issues does it resolve? As discussed earlier, for CTI to be effective, it must be Actionable, Timely, Relevant, and Accurate. These four elements form the foundation of robust CTI that ultimately provides visibility into adversary operations. Additionally, well-constructed CTI brings forth secondary benefits, such as:

Furthermore, from a leadership standpoint, high-quality CTI aids in fulfilling the business objective of minimizing risk as much as possible. As intelligence about an adversary targeting our business is gathered and analyzed, it empowers leadership to adequately assess the risk, formulate a contingency action plan if an incident occurs, and ultimately frame the problem and disseminate the information in a coherent and meaningful way.

As this information is compiled, it transforms into intelligence. This intelligence can then be classified into three different categories, each having varying degrees of relevance for different teams within our organization. These categories are:

In the diagram below, the ideal intersection is right at the core. At this convergence juncture, the Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) analyst is equipped to offer the most comprehensive and detailed portrait of the adversary and their modus operandi.

Strategic Intelligence is characterized by:

Example: A report containing strategic intelligence might outline the threat posed by APT28 (also known as Fancy Bear), a nation-state actor linked to the Russian government. This report could cover the group's past campaigns, its motivations (such as political espionage), targets (like governments, military, and security organizations), and long-term strategies. The report might also explore how the group adapts its tactics and tools over time, based on historical data and the geopolitical context.Operational Intelligence is characterized by:

Example: A report containing operational intelligence can provide detailed analysis of a ransomware campaign conducted by the REvil group. It would include how the group gains initial access (like through phishing or exploiting vulnerabilities), its lateral movement tactics (such as credential dumping and exploiting Windows admin tools), and its methods of executing the ransomware payload (maybe after hours to maximize damage and encrypt as many systems as possible).Tactical Intelligence is characterized by:

Example: A report containing tactical intelligence could include specific IP addresses, URLs, or domains linked to the REvil command and control servers, hashes of known REvil ransomware samples, specific file paths, registry keys, or mutexes associated with REvil, or even distinctive strings within the ransomware code. This type of information can be directly used by security technologies and incident responders to detect, prevent, and respond to specific threats.It's crucial to understand that there's a degree of overlap among these three types of intelligence. That's why we represent the intelligence in a Venn diagram. Tactical intelligence contributes to forming an operational picture and a strategic overview. The converse is also true.

Interpreting threat intelligence reports loaded with tactical intelligence and Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) is a task that requires a structured methodology to optimize our responsiveness as SOC analysts or threat hunters. Let's delve into a procedural, in-depth process using a theoretical scenario involving a threat intelligence report on an elaborate Emotet malware campaign:

Comprehending the Report's Scope and Narrative: The initial phase of interpreting the report involves comprehending its broader context. Suppose our report elucidates an ongoing Emotet campaign directed towards businesses in our sector. The report may offer macro-level insights about the attackers' objectives and the types of entities in their crosshairs. By grasping the narrative, we can assess the pertinence of the threat to our own business.Spotting and Classifying the IOCs: Tactical intelligence typically encompasses a list of IOCs tied to the threat. In the context of our Emotet scenario, these might include IP addresses linked to command-and-control (C2) servers, file hashes of the Emotet payloads, email addresses or subject lines leveraged in phishing campaigns, URLs of deceptive websites, or distinct Registry alterations by the malware. We should partition these IOCs into categories for more comprehensible understanding and actionable results: Network-based IOCs (IPs, domains), Host-based IOCs (file hashes, registry keys), and Email-based IOCs (email addresses, subject lines). Furthermore, IOCs could also contain Mutex names generated by the malware, SSL certificate hashes, specific API calls enacted by the malware, or even patterns in network traffic (such as specific User-Agents, HTTP headers, or DNS request patterns). Moreover, IOCs can be augmented with supplementary data. For instance, IP addresses can be supplemented with geolocation data, WHOIS information, or associated domains.Comprehending the Attack's Lifecycle: The report will likely depict the Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) deployed by the attackers, correspondingly mapped to the MITRE ATT\&CK framework. For the Emotet campaign, it might commence with a spear-phishing email (Initial Access), proceed to execute the payload (Execution), establish persistence (Persistence), execute defense evasion tactics (Defense Evasion), and ultimately exfiltrate data or deploy secondary payloads (Command and Control). Comprehending this lifecycle aids us in forecasting the attacker's moves and formulating an effective response.Analysis and Validation of IOCs: Not all IOCs hold the same utility or accuracy. We need to authenticate them, typically by cross-referencing with additional threat intelligence sources or databases such as VirusTotal or AlienVault's OTX. We also need to contemplate the age of IOCs. Older ones may not be as pertinent if the attacker has modified their infrastructure or tactics. Moreover, contextualizing IOCs is critical for their correct interpretation. For example, an IP address employed as a C2 server may also host legitimate websites due to IP sharing in cloud environments. Analysts should also consider the source's reliability and whether the IOC has been whitelisted in the past. Ultimately, understanding the false positive rate is crucial to avoid alert fatigue.Incorporating the IOCs into our Security Infrastructure: Once authenticated, we can integrate these IOCs into our security solutions. This might involve updating firewall rules with malicious IP addresses or domains, incorporating file hashes into our endpoint detection and response (EDR) solution, or creating new IDS/IPS signatures. For email-based IOCs, we can update our email security gateway or anti-spam solution. When implementing IOCs, we should consider the potential impact on business operations. For example, blocking an IP address might affect a business-critical service. In such cases, alerting rather than blocking might be more appropriate. Additionally, all changes should be documented and approved following change management procedures to maintain system integrity and avoid unintentional disruptions.Proactive Threat Hunting: Equipped with insights from the report, we can proactively hunt for signs of the Emotet threat in our environment. This might involve searching logs for network connections to the C2 servers, scanning endpoints for the identified file hashes, or checking email logs for the phishing email indicators. Threat hunting shouldn't be limited to searching for IOCs. We should also look for broader signs of TTPs described in the report. For instance, Emotet often employs PowerShell for execution and evasion. Therefore, we might hunt for suspicious PowerShell activity, even if it doesn't directly match an IOC. This approach aids in detecting variants of the threat not covered by the specific IOCs in the report.Continuous Monitoring and Learning: After implementing the IOCs, we must continually monitor our environment for any hits. Any detection should trigger a predefined incident response process. Furthermore, we should utilize the information gleaned from the report to enhance our security posture. This could involve user education around the phishing tactics employed by the Emotet group or improving our detection rules to catch the specific evasion techniques employed by this malware. While we should unquestionably learn from each report, we should also contribute back to the threat intelligence community. If we discover new IOCs or TTPs, these should be shared with threat intelligence platforms and ISACs/ISAOs (Information Sharing and Analysis Centers/Organizations) to aid other organizations in defending against the threat.This meticulous, step-by-step process, while tailored to our Emotet example, can be applied to any threat intelligence report containing tactical intelligence and IOCs. The secret is to be systematic, comprehensive, and proactive in our approach to maximize the value we derive from these reports.

The present Threat Intelligence report underlines the immediate menace posed by the organized cybercrime collective known as "Stuxbot". The group initiated its phishing campaigns earlier this year and operates with a broad scope, seizing upon opportunities as they arise, without any specific targeting strategy – their motto seems to be anyone, anytime. The primary motivation behind their actions appears to be espionage, as there have been no indications of them exfiltrating sensitive blueprints, proprietary business information, or seeking financial gain through methods such as ransomware or blackmail.

Microsoft WindowsWindows UsersComplete takeover of the victim's computer / Domain escalationCriticalThe group primarily leverages opportunistic-phishing for initial access, exploiting data from social media, past breaches (e.g., databases of email addresses), and corporate websites. There is scant evidence suggesting spear-phishing against specific individuals.

The document compiles all known Tactics Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) and Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) linked to the group, which are currently under continuous refinement. This preliminary sketch is confidential and meant exclusively for our partners, who are strongly advised to conduct scans of their infrastructures to spot potential successful breaches at the earliest possible stage.

In summary, the attack sequence for the initially compromised device can be laid out as follows:

Initial Breach

The phishing email is relatively rudimentary, with the malware posing as an invoice file. Here's an example of an actual phishing email that includes a link leading to a OneNote file:

Our forensic investigation into these attacks revealed that the link directs to a OneNote file, which has consistently been hosted on a file hosting service (e.g., Mega.io or similar platforms).

This OneNote file masquerades as an invoice featuring a 'HIDDEN' button that triggers an embedded batch file. This batch file, in turn, fetches PowerShell scripts, representing stage 0 of the malicious payload.

RAT Characteristics

The RAT deployed in these attacks is modular, implying that it can be augmented with an infinite range of capabilities. While only a few features are accessible once the RAT is staged, we have noted the use of tools that capture screen dumps, execute Mimikatz, provide an interactive CMD shell on compromised machines, and so forth.

Persistence

All persistence mechanisms utilized to date have involved an EXE file deposited on the disk.

Lateral Movement

So far, we have identified two distinct methods for lateral movement:

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

The following provides a comprehensive inventory of all identified IOCs to this point.

OneNote File:

Staging Entity (PowerShell Script):

Command and Control (C\&C) Nodes:

Cryptographic Hashes of Involved Files (SHA256):

Navigate to the bottom of this section and click on Click here to spawn the target system!

Now, navigate to http://[Target IP]:5601, click on the side navigation toggle, and click on "Discover". Then, click on the calendar icon, specify "last 15 years", and click on "Apply".

Please also specify a Europe/Copenhagen timezone, through the following link http://[Target IP]:5601/app/management/kibana/settings.

The Available Data

The cybersecurity strategy implemented is predicated on the utilization of the Elastic stack as a SIEM solution. Through the "Discover" functionality we can see logs from multiple sources. These sources include:

Windows audit logs (categorized under the index pattern windows*)System Monitor (Sysmon) logs (also falling under the index pattern windows*, more about Sysmon here)PowerShell logs (indexed under windows* as well, more about PowerShell logs here)Zeek logs, a network security monitoring tool (classified under the index pattern zeek*)Our available threat intelligence stems from March 2023, hence it's imperative that our Kibana setup scans logs dating back at least to this time frame. Our "windows" index contains around 118,975 logs, while the "zeek" index houses approximately 332,261 logs.

The Environment

Our organization is relatively small, with about 200 employees primarily engaged in online marketing activities, thus our IT resource requirement is minimal. Office applications are the primary software in use, with Gmail serving as our standard email provider, accessed through a web browser. Microsoft Edge is the default browser on our company laptops. Remote technical support is provided through TeamViewer, and all our company devices are managed via Active Directory Group Policy Objects (GPOs). We're considering a transition to Microsoft Intune for endpoint management as part of an upcoming upgrade from Windows 10 to Windows 11.

The Task

Our task centers around a threat intelligence report concerning a malicious software known as "Stuxbot". We're expected to use the provided Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) to investigate whether there are any signs of compromise in our organization.

The Hunt

The sequence of hunting activities is premised on the hypothesis of a successful phishing email delivering a malicious OneNote file. If our hypothesis had been the successful execution of a binary with a hash matching one from the threat intelligence report, we would have undertaken a different sequence of activities.

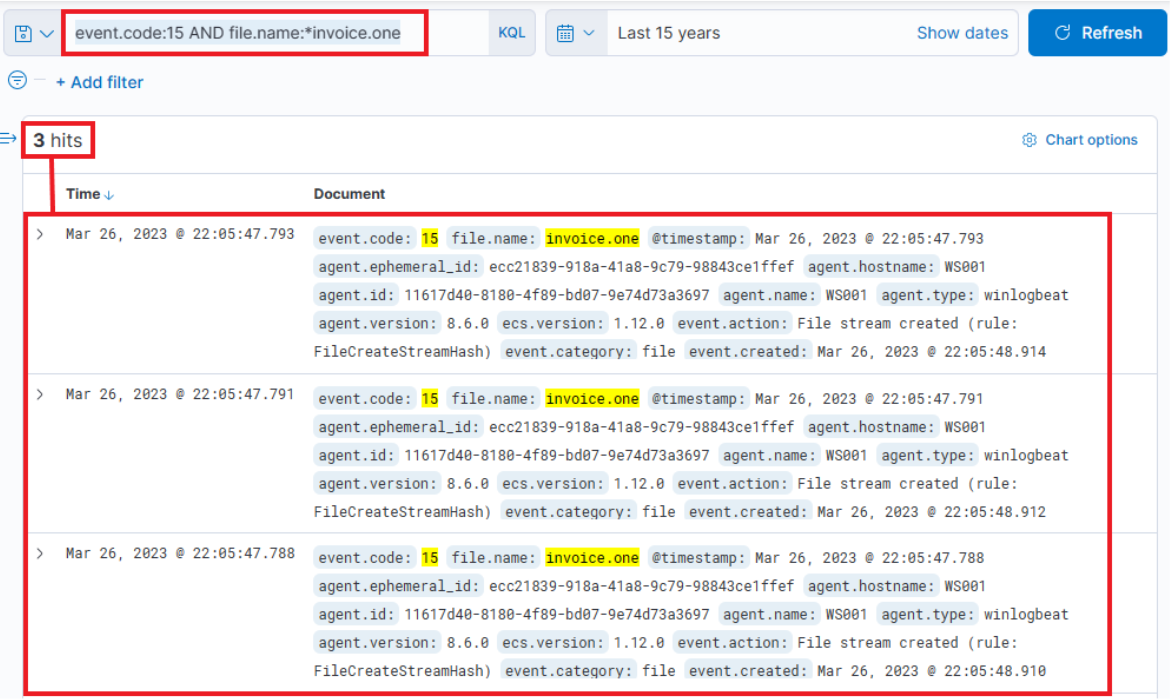

The report indicates that initial compromises all took place via "invoice.one" files. Despite this, we must continue to conduct searches on other IOCs as the threat actors may have introduced different delivery techniques between the time the report was created and the present. Back to the "invoice.one" files, a comprehensive search can be initiated based on Sysmon Event ID 15 (FileCreateStreamHash), which represents a browser file download event. We're assuming that a potentially malicious OneNote file was downloaded from Gmail, our organization's email provider.

Our search query should be the following.

Related fields: winlog.event_id or event.code and file.name

Hunting For Stuxbot

event.code:15 AND file.name:*invoice.one

While this development could imply serious implications, it's not yet confirmed if this file is the same one mentioned in the report. Further, signs of execution have not been probed. If we extend the event log to display its complete content, it'll reveal that MSEdge was the application (as indicated by process.name or process.executable) used to download the file, which was stored in the Downloads folder of an employee named Bob.

The timestamp to note is: March 26, 2023 @ 22:05:47

We can corroborate this information by examining Sysmon Event ID 11 (File create) and the "invoice.one" file name. This method is especially effective when browsers aren't involved in the file download process. The query is similar to the previous one, but the asterisk is at the end as the file name includes only the filename with an additional Zone Identifier, likely indicating that the file originated from the internet.

Related fields: winlog.event_id or event.code and file.name

Hunting For Stuxbot

event.code:11 AND file.name:invoice.one*

It's relatively easy to deduce that the machine which reported the "invoice.one" file has the hostname WS001 (check the host.hostname or host.name fields of the Sysmon Event ID 11 event we were just looking at) and an IP address of 192.168.28.130, which can be confirmed by checking any network connection event (Sysmon Event ID 3) from this machine (execute the following query event.code:3 AND host.hostname:WS001 and check the source.ip field).

If we inspect network connections leveraging Sysmon Event ID 3 (Network connection) around the time this file was downloaded, we'll find that Sysmon has no entries. This is a common configuration to avoid capturing network connections created by browsers, which could lead to an overwhelming volume of logs, particularly those related to our email provider.

This is where Zeek logs prove invaluable. We should filter and examine the DNS queries that Zeek has captured from WS001 during the interval from 22:05:00 to 22:05:48, when the file was downloaded.

Our Zeek query will search for a source IP matching 192.168.28.130, and since we're querying about DNS queries, we'll only pick logs that have something in the dns.question.name field. Note that this will return a lot of common noise, like google.com, etc., so it's necessary to filter that out. Here's the query and some filters.

Related fields: source.ip and dns.question.name

Hunting For Stuxbot

source.ip:192.168.28.130 AND dns.question.name:*

We can easily identify major sources of noise by looking at the most common values that Kibana has detected (click on a field as follows), and then apply a filter on the known noisy ones.

As part of our search process, since we're interested in DNS names, we'd like to display only the dns.question.name field in the result table. Please note the specified time March 26th 2023 @ 22:05:00 to March 26th 2023 @ 22:05:48.

Scrolling down the table of entries, we observe the following activities.

From this data, we infer that the user accessed Google Mail, followed by interaction with "file.io", a known hosting provider. Subsequently, Microsoft Defender SmartScreen initiated a file scan, typically triggered when a file is downloaded via Microsoft Edge. Expanding the log entry for file.io reveals the returned IP addresses (dns.answers.data or dns.resolved_ip or zeek.dns.answers fields) as follows.

34.197.10.85, 3.213.216.16

Now, if we run a search for any connections to these IP addresses during the same timeframe as the DNS query, it leads to the following findings.

This information corroborates that a user, Bob, successfully downloaded the file "invoice.one" from the hosting provider "file.io".

At this juncture, we have two choices: we can either cross-reference the data with the Threat Intel report to identify overlapping information within our environment, or we can conduct an Incident Response (IR)-like investigation to trace the sequence of events post the OneNote file download. We choose to proceed with the latter approach, tracking the subsequent activities.

Hypothetically, if "invoice.one" was accessed, it would be opened with the OneNote application. So, the following query will flag the event, if it transpired. Note: The time frame we specified previously should be removed, setting it to, say, 15 years again. The dns.question.name column should also be removed.

Related fields: winlog.event_id or event.code and process.command_line

Hunting For Stuxbot

event.code:1 AND process.command_line:*invoice.one*

Indeed, we find that the OneNote file was accessed shortly after its download, with a delay of roughly 6 seconds. Now, with OneNote.exe in operation and the file open, we can speculate that it either contains a malicious link or a malevolent file attachment. In either case, OneNote.exe will initiate either a browser or a malicious file. Therefore, we should scrutinize any new processes where OneNote.exe is the parent process. The corresponding query is the following. Sysmon Event ID 1 (Process creation) is utilized.

Related fields: winlog.event_id or event.code and process.parent.name

Hunting For Stuxbot

event.code:1 AND process.parent.name:"ONENOTE.EXE"

The results of this query present three hits. However, one of these (the bottom one) falls outside the relevant time frame and can be dismissed. Evaluating the other two results:

Now we can establish a connection between "OneNote.exe", the suspicious "invoice.one", and the execution of "cmd.exe" that initiates "invoice.bat" from a temporary location (highly likely due to its attachment inside the OneNote file). The question now is, has this batch script instigated anything else? Let's search if a parent process with a command line argument pointing to the batch file has spawned any child processes with the following query.

Related fields: winlog.event_id or event.code and process.parent.command_line

Hunting For Stuxbot

event.code:1 AND process.parent.command_line:*invoice.bat*

This query returns a single result: the initiation of PowerShell, and the arguments passed to it appear conspicuously suspicious (note that we have added process.name, process.args, and process.pid as columns)! A command to download and execute content from Pastebin, an open text hosting provider! We can try to access and see if the content, which the script attempted to download, is still available (by default, it won't expire!).

Indeed, it is! This is referred to in the Threat Intelligence report, stating that a PowerShell Script from Pastebin was downloaded.

To figure out what PowerShell did, we can filter based on the process ID and name to get an overview of activities. Note that we have added the event.code field as a column.

Related fields: process.pid and process.name

Hunting For Stuxbot

process.pid:"9944" and process.name:"powershell.exe"

Immediately, we can observe intriguing output indicating file creation, attempted network connections, and some DNS resolutions leverarging Sysmon Event ID 22 (DNSEvent). By adding some additional informative fields (file.path, dns.question.name, and destination.ip ) as columns to that view, we can expand it.

Now, this presents us with rich data on the activities. Ngrok was likely employed as C2 (to mask malicious traffic to a known domain). If we examine the connections above the DNS resolution for Ngrok, it points to the destination IP Address 443, implying that the traffic was encrypted.

The dropped EXE is likely intended for persistence. Its distinctive name should facilitate determining whether it was ever executed. It's important to note the timestamps – there is some time lapse between different activities, suggesting it's less likely to have been scripted but perhaps an actual human interaction took place (unless random sleep occurred between the executed actions). The final actions that this process points to are a DNS query for DC1 and connections to it.

Let's review Zeek data for information on the destination IP address 18.158.249.75 that we just discovered. Note that the source.ip, destination.ip, and destination.port fields were added as columns.

Intriguingly, the activity seems to have extended into the subsequent day. The reason for the termination of the activity is unclear... Was there a change in C2 IP? Or did the attack simply halt? Upon inspecting DNS queries for "ngrok.io", we find that the returned IP (dns.answers.data) has indeed altered. Note that the dns.answers.data field was added as a column.

The newly discovered IP also indicates that connections continued consistently over the following days.

Thus, it's apparent that there is sustained network activity, and we can deduce that the C2 has been accessed continually. Now, as for the earlier uploaded executable file "default.exe" – did that ever execute? By probing the Sysmon logs for a process with that name, we can ascertain this. Note that the process.name, process.args, event.code, file.path, destination.ip, and dns.question.name fields were added as columns.

Related field: process.name

Hunting For Stuxbot

process.name:"default.exe"

Indeed, it has been executed – we can instantly discern that the executable initiated DNS queries for Ngrok and established connections with the C2 IP addresses. It also uploaded two files "svchost.exe" and "SharpHound.exe". SharpHound is a recognized tool for diagramming Active Directory and identifying attack paths for escalation. As for svchost.exe, we're unsure – is it another malicious agent? The name implies it attempts to mimic the legitimate svchost file, which is part of the Windows Operating System.

If we scroll up there's further activity from this executable, including the uploading of "payload.exe", a VBS file, and repeated uploads of "svchost.exe".

At this juncture, we're left with one question: did SharpHound execute? Did the attacker acquire information about Active Directory? We can investigate this with the following query (since it was an on-disk executable file).

Related field: process.name

process.name:"SharpHound.exe"

Indeed, the tool appears to have been executed twice, roughly 2 minutes apart from each other.

It's vital to note that Sysmon has flagged "default.exe" with a file hash (process.hash.sha256 field) that aligns with one found in the Threat Intel report. This leads us to question whether this executable has been detected on other devices within the environment. Let's conduct a broad search. Note that the host.hostname field was added as a column.

Related field: process.hash.sha256

process.hash.sha256:018d37cbd3878258c29db3bc3f2988b6ae688843801b9abc28e6151141ab66d4

Files with this hash value have been found on WS001 and PKI, indicating that the attacker has also breached the PKI server at a minimum. It also appears that a backdoor file has been placed under the profile of user "svc-sql1", suggesting that this user's account is likely compromised.

Expanding the first instance of "default.exe" execution on PKI, we notice that the parent process was "PSEXESVC", a component of PSExec from SysInternals – a tool often used for executing commands remotely, frequently utilized for lateral movement in Active Directory breaches.

Further down the same log, we notice "svc-sql1" in the user.name field, thereby confirming the compromise of this user.

How was the password of "svc-sql1" compromised? The only plausible explanation from the available data so far is potentially the earlier uploaded PowerShell script, seemingly designed for Password Bruteforcing. We know that this was uploaded on WS001, so we can check for any successful or failed password attempts from that machine, excluding those for Bob, the user of that machine (and the machine itself).

Related fields: winlog.event_id or event.code, winlog.event_data.LogonType, and source.ip

(event.code:4624 OR event.code:4625) AND winlog.event_data.LogonType:3 AND source.ip:192.168.28.130

The results are quite intriguing – two failed attempts for the administrator account, roughly around the time when the initial suspicious activity was detected. Subsequently, there were numerous successful logon attempts for "svc-sql1". It appears they attempted to crack the administrator's password but failed. However, two days later on the 28th, we observe successful attempts with svc-sql1.

At this stage, we have amassed a significant amount of information to present and initiate a comprehensive incident response, in accordance with company policies.