| Description | 64-bit Register (8-bytes) | 8-bit Register (1-bytes) |

|---|---|---|

| Data/Arguments Registers | ||

| Syscall Number/Return value | rax | al |

| Callee Saved | rbx | bl |

| 1st arg | rdi | dil |

| 2nd arg | rsi | sil |

| 3rd arg | rdx | dl |

| 4th arg - Loop Counter | rcx | cl |

| 5th arg | r8 | r8b |

| 6th arg | r9 | r9b |

| Pointer Registers | ||

| Base Stack Pointer | rbp | bpl |

| Current/Top Stack Pointer | rsp | spl |

| Instruction Pointer 'call only' | rip | ipl |

| Command | Description |

nasm -f elf64 helloWorld.s | Assemble code |

ld -o helloWorld helloWorld.o | Link code |

ld -o fib fib.o -lc --dynamic-linker /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 | Link code with libc functions |

objdump -M intel -d helloWorld | Disassemble .text section |

objdump -M intel --no-show-raw-insn --no-addresses -d helloWorld | Show binary assembly code |

objdump -sj .data helloWorld | Disassemble .data section |

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

gdb -q ./helloWorld |

Open binary in gdb |

info functions |

View binary functions |

info variables |

View binary variables |

registers |

View registers |

disas _start |

Disassemble label/function |

b _start |

Break label/function |

b *0x401000 |

Break address |

r |

Run the binary |

x/4xg $rip |

Examine register "x/ count-format-size $register" |

si |

Step to the next instruction |

s |

Step to the next line of code |

ni |

Step to the next function |

c |

Continue to the next break point |

patch string 0x402000 "Patched!\\x0a" |

Patch address value |

set $rdx=0x9 |

Set register value |

| Instruction | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Data Movement | ||

mov |

Move data or load immediate data | mov rax, 1 -> rax = 1 |

lea |

Load an address pointing to the value | lea rax, [rsp+5] -> rax = rsp+5 |

xchg |

Swap data between two registers or addresses | xchg rax, rbx -> rax = rbx, rbx = rax |

| Unary Arithmetic Instructions | ||

inc |

Increment by 1 | inc rax -> rax++ or rax += 1 -> rax = 2 |

dec |

Decrement by 1 | dec rax -> rax-- or rax -= 1 -> rax = 0 |

| Binary Arithmetic Instructions | ||

add |

Add both operands | add rax, rbx -> rax = 1 + 1 -> 2 |

sub |

Subtract Source from Destination (i.e rax = rax - rbx) |

sub rax, rbx -> rax = 1 - 1 -> 0 |

imul |

Multiply both operands | imul rax, rbx -> rax = 1 * 1 -> 1 |

| Bitwise Arithmetic Instructions | ||

not |

Bitwise NOT (invert all bits, 0->1 and 1->0) | not rax -> NOT 00000001 -> 11111110 |

and |

Bitwise AND (if both bits are 1 -> 1, if bits are different -> 0) | and rax, rbx -> 00000001 AND 00000010 -> 00000000 |

or |

Bitwise OR (if either bit is 1 -> 1, if both are 0 -> 0) | or rax, rbx -> 00000001 OR 00000010 -> 00000011 |

xor |

Bitwise XOR (if bits are the same -> 0, if bits are different -> 1) | xor rax, rbx -> 00000001 XOR 00000010 -> 00000011 |

| Loops | ||

mov rcx, x |

Sets loop (rcx) counter to x |

mov rcx, 3 |

loop |

Jumps back to the start of loop until counter reaches 0 |

loop exampleLoop |

| Branching | ||

jmp |

Jumps to specified label, address, or location | jmp loop |

jz |

Destination equal to Zero | D = 0 |

jnz |

Destination Not equal to Zero | D != 0 |

js |

Destination is Negative | D < 0 |

jns |

Destination is Not Negative (i.e. 0 or positive) | D >= 0 |

jg |

Destination Greater than Source | D > S |

jge |

Destination Greater than or Equal Source | D >= S |

jl |

Destination Less than Source | D < S |

jle |

Destination Less than or Equal Source | D <= S |

cmp |

Sets RFLAGS by subtracting second operand from first operand (i.e. first - second) |

cmp rax, rbx -> rax - rbx |

| Stack | ||

push |

Copies the specified register/address to the top of the stack | push rax |

pop |

Moves the item at the top of the stack to the specified register/address | pop rax |

| Functions | ||

call |

push the next instruction pointer rip to the stack, then jumps to the specified procedure |

call printMessage |

ret |

pop the address at rsp into rip, then jump to it |

ret |

| Command | Description |

cat /usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/asm/unistd_64.h | grep write | Locate write syscall number |

man -s 2 write | write syscall man page |

man -s 3 printf | printf libc man page |

Syscall Calling Convention

raxsyscall assembly instruction to call itFunction Calling Convention

Save Registers on the stack (Caller Saved)Function Arguments (like syscalls)Stack AlignmentReturn Value (in rax)| Command | Description | |

|---|---|---|

pwn asm 'push rax' -c 'amd64' |

Instruction to shellcode | |

pwn disasm '50' -c 'amd64' |

Shellcode to instructions | |

python3 shellcoder.py helloworld |

Extract binary shellcode | |

python3 loader.py '4831..0f05 |

Run shellcode | |

python assembler.py '4831..0f05 |

Assemble shellcode into binary | |

| Shellcraft | ||

pwn shellcraft -l 'amd64.linux' |

List available syscalls | |

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.sh |

Generate syscalls shellcode | |

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.sh -r |

Run syscalls shellcode | |

| Msfvenom | ||

| `msfvenom -l payloads \ | grep 'linux/x64'` | List available syscalls |

msfvenom -p 'linux/x64/exec' CMD='sh' -a 'x64' --platform 'linux' -f 'hex' |

Generate syscalls shellcode | |

msfvenom -p 'linux/x64/exec' CMD='sh' -a 'x64' --platform 'linux' -f 'hex' -e 'x64/xor' |

Generate encoded syscalls shellcode |

Shellcoding Requirements

00 Most of our interaction with our personal computers and smartphones is done through the operating system and other applications. These applications are usually developed using high-level languages, like C++, Java, Python, and many others. We also know that each of these devices has a core processor that runs all of the necessary processes to execute systems and applications, along with Random Access Memory (RAM), Video Memory, and other similar components.

However, these physical components cannot interpret or understand high-level languages, as they can essentially only process 1's and 0's. This is where Assembly language comes in, as a low-level language that can write direct instructions the processors can understand. Since the processor can only process binary data "i.e. 1's and 0's", it would be challenging for humans to interact with processors without referring to manuals to know which hex code runs which instruction.

This is why low-level assembly languages were built. By using Assembly, developers can write human-readable machine instructions, which are then assembled into their machine code equivalent, so that the processor can directly run them. This is why some refer to Assembly language as symbolic machine code. For example, the Assembly code 'add rax, 1' is much more intuitive and easier to remember than its equivalent machine shellcode '4883C001', and easier to remember than the equivalent binary machine code '01001000 10000011 11000000 00000001'. As we can see, without Assembly language, it is very challenging to write machine instructions or directly interact with the processor.

Machine code is often represented as Shellcode, a hex representation of machine code bytes. Shellcode can be translated back to its Assembly counterpart and can also be loaded directly into memory as binary instructions to be executed.

As there are different processor designs, each processor understands a different set of machine instructions and a different Assembly language. In the past, applications had to be written in assembly for each processor, so it was not easy to develop an application for multiple processors. In the early 1970's, high-level languages (like C) were developed to make it possible to write a single easy to understand code that can work on any processor without rewriting it for each processor. To be more specific, this was made possible by creating compilers for each language.

When high-level code is compiled, it is translated into assembly instructions for the processor it is being compiled for, which is then assembled into machine code to run on the processor. This is why compilers are built for various languages and various processors to convert the high-level code into assembly code and then machine code that matches the running processor.

Later on, interpreted languages were developed, like Python, PHP, Bash, JavaScript, and others, which are usually not compiled but are interpreted during run time. These types of languages utilize pre-built libraries to run their instructions. These libraries are typically written and compiled in other high-level languages like C or C++. So when we issue a command in an interpreted language, it would use the compiled library to run that command, which uses its assembly code/machine code to perform all the instructions necessary to run this command on the processor.

Let's take a basic 'Hello World!' program that prints these words on the screen and show how it changes from high-level to machine code. In an interpreted language, like Python, it would be the following basic line:

Code: python

print("Hello World!")

If we run this Python line, it would be essentially executing the following C code:

Code: c

#include <unistd.h>

int main()

{

write(1, "Hello World!", 12);

_exit(0);

}

Note: the actual C source code is much longer, but the above is the essence of how the string 'Hello World!' is printed. If you are ever interested in knowing more, you can check out the source code of the Python3 print function at this link and this link

The above C code uses the Linux write syscall, built-in for processes to write to the screen. The same syscall called in Assembly looks like the following:

Code: nasm

mov rax, 1

mov rdi, 1

mov rsi, message

mov rdx, 12

syscall

mov rax, 60

mov rdi, 0

syscall

As we can see, when the write syscall is called in C or Assembly, both are using 1, the text, and 12 as the arguments. This will be covered more in-depth later in the module. From this point, Assembly code, shellcode, and binary machine code are mostly identical but written in different formats. The previous Assembly code can be assembled into the following hex machine code (i.e., shellcode):

Code: shellcode

48 c7 c0 01

48 c7 c7 01

48 8b 34 25

48 c7 c2 0c

0f 05

48 c7 c0 3c

48 c7 c7 00

0f 05

Finally, for the processor to execute the instructions linked to this machine, it would have to be translated into binary, which would look like the following:

Code: binary

01001000 11000111 11000000 00000001

01001000 11000111 11000111 00000001

01001000 10001011 00110100 00100101

01001000 11000111 11000010 00001101

00001111 00000101

01001000 11000111 11000000 00111100

01001000 11000111 11000111 00000000

00001111 00000101

A CPU uses different electrical charges for a 1 and a 0, and hence can calculate these instructions from the binary data once it receives them.

Note: With multi-platform languages, like Java, the code is compiled into a Java Bytecode, which is the same for all processors/systems, and is then compiled to machine code by the local Java Runtime environment. This is what makes Java relatively slower than other languages like C++ that compile directly into machine code. Languages like C++ are more suitable for processor intensive applications like games.

We now see how computer languages progressed from assembly language unique for each processor to high-level languages that can work on any device without even needing to be compiled.

Understanding assembly language instructions is critical for binary exploitation, which is an essential part of penetration testing. When it comes to exploiting compiled programs, the only way to attack them would be through their binaries. To disassemble, debug, and follow binary instructions in memory and find potential vulnerabilities, we must have a basic understanding of Assembly language and how it flows through the CPU components.

This is why once we start learning binary exploitation techniques, like buffer overflows, ROP chains, heap exploitation, and others, we will be dealing a lot with assembly instructions and following them in memory. Furthermore, to exploit these vulnerabilities, we will have to build custom exploits that use assembly instructions to manipulate the code while in memory and inject assembly shellcode to be executed.

Learning Intel x86 Assembly Language is crucial for writing exploits for binaries on modern machines. In addition to Intel x86, ARM is becoming more common, as most modern smartphones and some modern laptops like the M1 MacBook Pro feature ARM processors. Exploiting binaries in these systems requires ARM Assembly knowledge. This module will not cover ARM Assembly Language. That being said, Assembly Language basics will undoubtedly be helpful to anyone willing to learn ARM Assembly since the two languages have a lot of similarities.

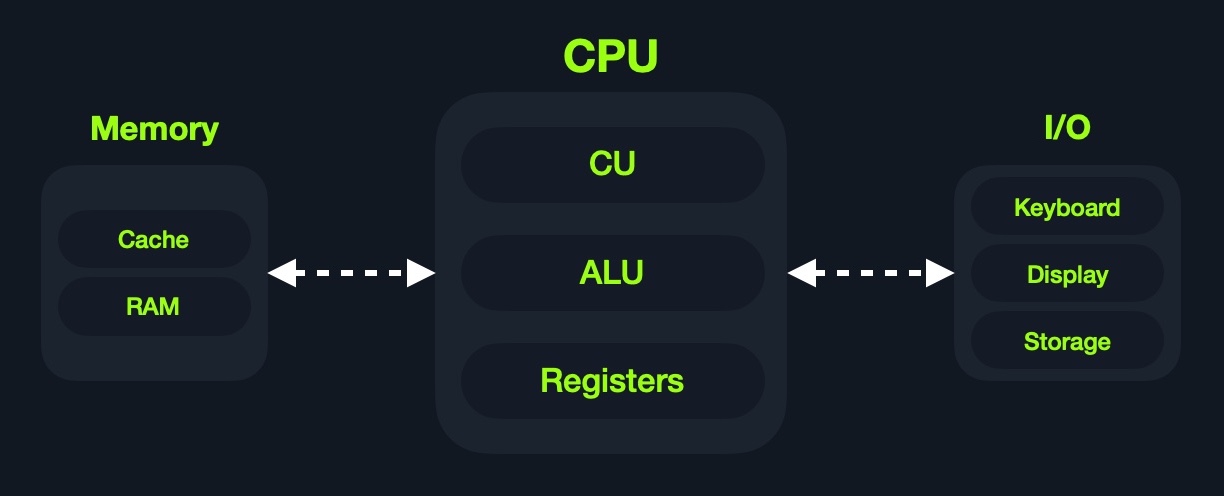

Today, most modern computers are built on what is known as the Von Neumann Architecture, which was developed back in 1945 by Von Neumann to enable the creation of "General-Purpose Computers" as Alan Turing described them at the time. Alan Turing in turn, based his ideas on Charles Babbage's mid-19th century "Programmable Computer" concept. Note that all of these people were mathematicians.

This architecture executes machine code to perform specific algorithms. It mainly consists of the following elements:

Furthermore, the CPU itself consists of three main components:

Though very old, this architecture is still the basis of most modern computers, servers, and even smartphones.

Assembly languages mainly work with the CPU and memory. This is why it is crucial to understand the general design of computer architecture, so when we start using assembly instructions to move and process data, we know where it's going and coming from and how fast/expensive each instruction is.

Furthermore, basic and advanced binary exploitation requires a proper understanding of computer architecture. With basic stack overflows, we only need to be aware of the general design. Once we start using ROP and Heap exploits, our understanding should be profound. Let us now take a deeper look into some essential components.

A computer's memory is where the temporary data and instructions of currently running programs are located. A computer's memory is also known as Primary Memory. It is the primary location the CPU uses to retrieve and process data. It does so very frequently (billions of times a second), so the memory must be extremely fast in storing and retrieving data and instructions.

There are two main types of memory:

CacheRandom Access Memory (RAM)Cache

Cache memory is usually located within the CPU itself and hence is extremely fast compared to RAM, as it runs at the same clock speed as the CPU. However, it is very limited in size and very sophisticated, and expensive to manufacture due to it being so close to the CPU core.

Since RAM clock speed is usually much slower than the CPU cores, in addition to it being far from the CPU, if a CPU had to wait for the RAM to retrieve each instruction, it would effectively be running at much lower clock speeds. This is the main benefit of cache memory. It enables the CPU to access the upcoming instructions and data quicker than retrieving them from RAM.

There are usually three levels of cache memory, depending on their closeness to the CPU core:

| Level | Description |

|---|---|

Level 1 Cache |

Usually in kilobytes, the fastest memory available, located in each CPU core. (Only registers are faster.) |

Level 2 Cache |

Usually in megabytes, extremely fast (but slower than L1), shared between all CPU cores. |

Level 3 Cache |

Usually in megabytes (larger than L2), faster than RAM but slower than L1/L2. (Not all CPUs use L3.) |

RAM

RAM is much larger than cache memory, coming in sizes ranging from gigabytes up to terabytes. RAM is also located far away from the CPU cores and is much slower than cache memory. Accessing data from RAM addresses takes many more instructions.

For example, retrieving an instruction from the registers takes only one clock cycle, and retrieving it from the L1 cache takes a few cycles, while retrieving it from RAM takes around 200 cycles. When this is done billions of times a second, it makes a massive difference in the overall execution speed.

In the past, with 32-bit addresses, memory addresses were limited from 0x00000000 to 0xffffffff. This meant that the maximum possible RAM size was 232 bytes, which is only 4 gigabytes, at which point we run out of unique addresses. With 64-bit addresses, the range is now up to 0xffffffffffffffff, with a theoretical maximum RAM size of 264 bytes, which is around 18.5 exabytes (18.5 million terabytes), so we shouldn't be running out of memory addresses anytime soon.

When a program is run, all of its data and instructions are moved from the storage unit to the RAM to be accessed when needed by the CPU. This happens because accessing them from the storage unit is much slower and will increase data processing times. When a program is closed, its data is removed or made available to re-use from the RAM.

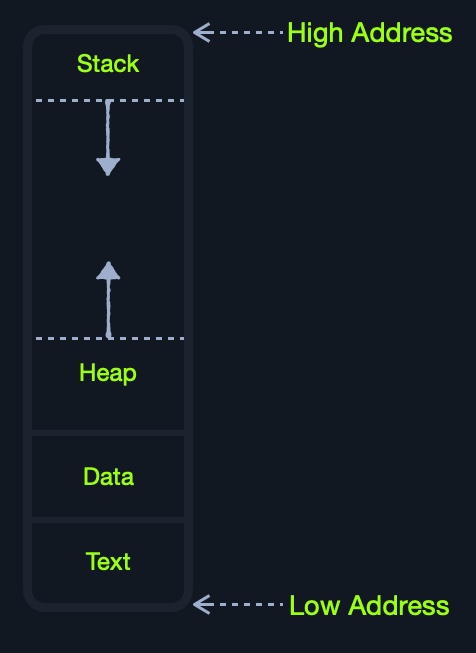

As we can see, the RAM is split into four main segments:

| Segment | Description |

|---|---|

Stack |

Has a Last-in First-out (LIFO) design and is fixed in size. Data in it can only be accessed in a specific order by push-ing and pop-ing data. |

Heap |

Has a hierarchical design and is therefore much larger and more versatile in storing data, as data can be stored and retrieved in any order. However, this makes the heap slower than the Stack. |

Data |

Has two parts: Data, which is used to hold variables, and .bss, which is used to hold unassigned variables (i.e., buffer memory for later allocation). |

Text |

Main assembly instructions are loaded into this segment to be fetched and executed by the CPU. |

Although this segmentation applies to the entire RAM, each application is allocated its Virtual Memory when it is run. This means that each application would have its own stack, heap, data, and text segments.

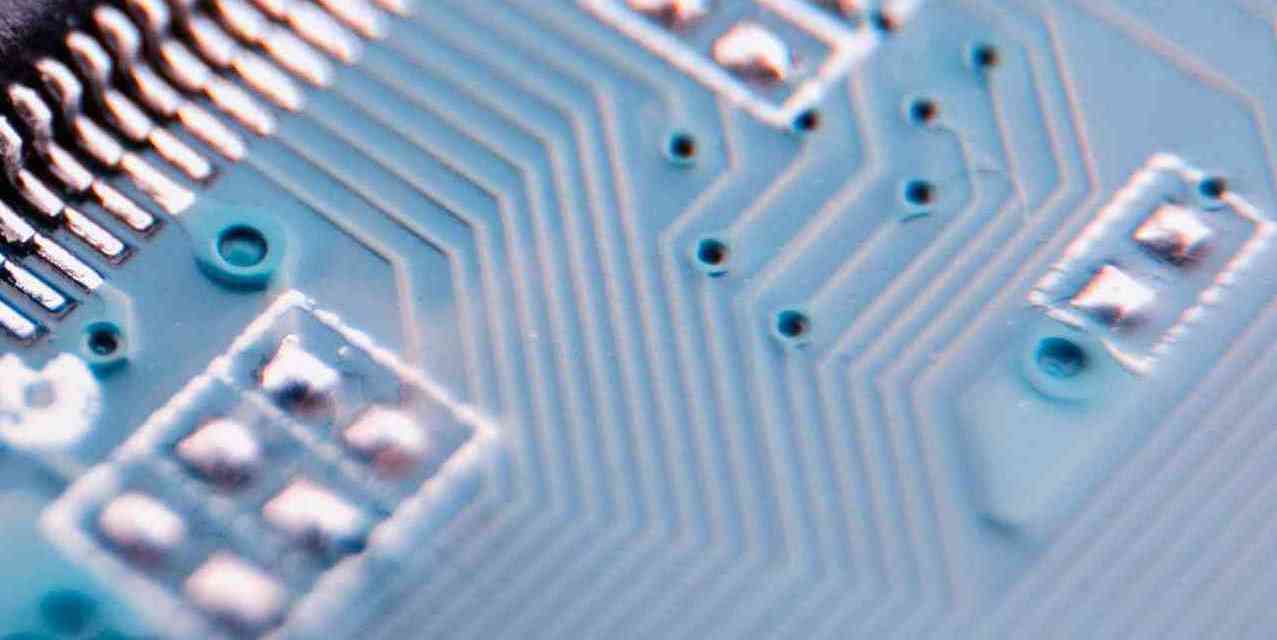

Finally, we have the Input/Output devices, like the keyboard, the screen, or the long-term storage unit, also known as Secondary Memory. The processor can access and control IO devices using Bus Interfaces, which act as 'highways' to transfer data and addresses, using electrical charges for binary data.

Each Bus has a capacity of bits (or electrical charges) it can carry simultaneously. This usually is a multiple of 4-bits, ranging up to 128-bits. Bus interfaces are also usually used to access memory and other components outside the CPU itself. If we take a closer look at a CPU or a motherboard, we can see the bus interfaces all over them:

Unlike primary memory that is volatile and stores temporary data and instructions as the programs are running, the storage unit stores permanent data, like the operating system files or entire applications and their data.

The storage unit is the slowest to access. First, because they are the farthest away from the CPU, accessing them through bus interfaces like SATA or USB takes much longer to store and retrieve the data. They are also slower in their design to allow more data storage. Αs long as there is more data to go through, they will be slower.

There has been a shift from classic magnetic storage units, like tapes or Hard Disk Drives (HDD), to Solid-State Drives (SSD) in recent years. This is because SSD's utilize a similar design to RAM's, using non-volatile circuitry that retains data even without electricity. This made storage units much faster in storing and retrieving data. Still, since they are far away from the CPU and connected through special interfaces, they are the slowest unit to access.

As we can see from the above, the further away a component is from the CPU core, the slower it is. Also, the more data it can hold, the slower it is, as it simply has to go through more to fetch the data. The below table summarizes each component, its size, and its speed:

| Component | Speed | Size |

|---|---|---|

Registers |

Fastest | Bytes |

L1 Cache |

Fastest, other than Registers | Kilobytes |

L2 Cache |

Very fast | Megabytes |

L3 Cache |

Fast, but slower than the above | Megabytes |

RAM |

Much slower than all of the above | Gigabytes-Terabytes |

Storage |

Slowest | Terabytes and more |

The speed here is relative depending on the CPU clock speed. Now that we have a general idea of the computer architecture, we'll discuss Registers and the CPU architecture in the next section.

The Central Processing Unit (CPU) is the main processing unit within a computer. The CPU contains both the Control Unit (CU), which is in charge of moving and controlling data, and the Arithmetic/Logic Unit (ALU), which is in charge of performing various arithmetics and logical calculations as requested by a program through the assembly instructions.

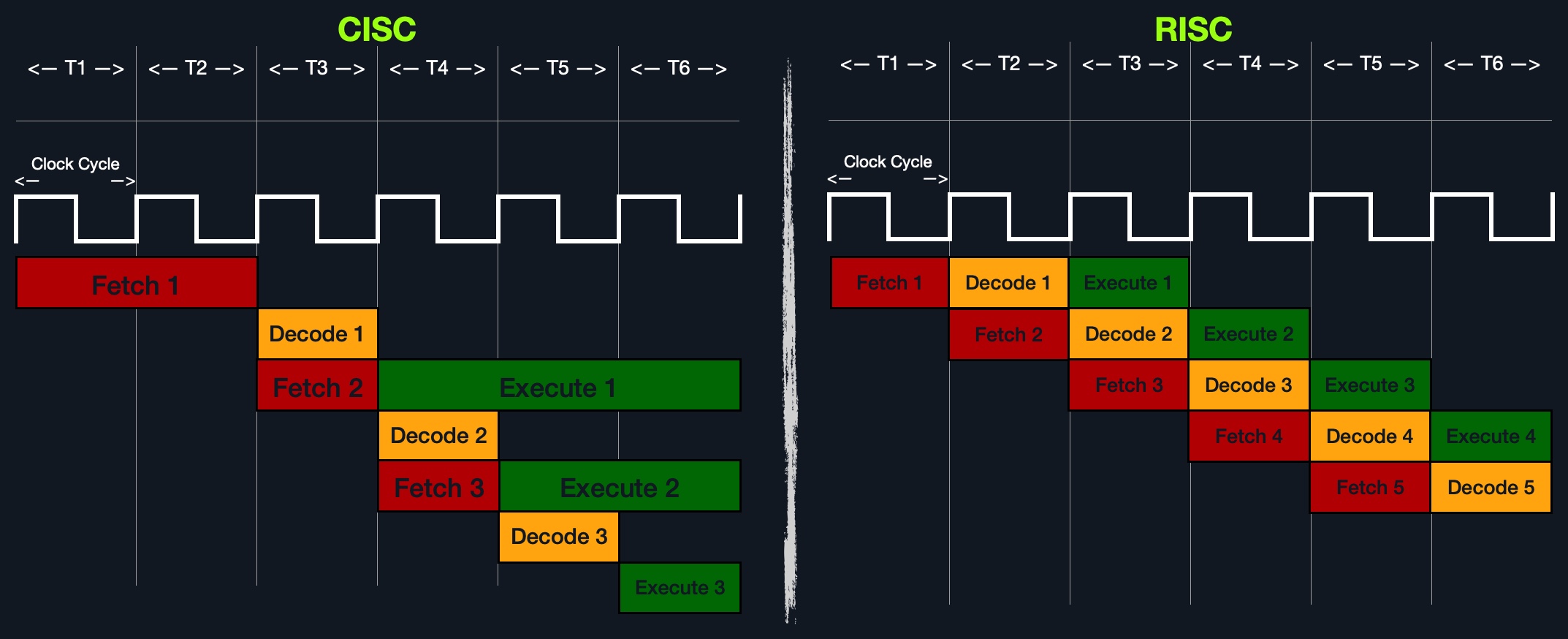

The manner in which and how efficiently a CPU processes its instructions depends on its Instruction Set Architecture (ISA). There are multiple ISA's in the industry, each having its way of processing data. RISC architecture is based on processing more simple instructions, which takes more cycles, but each cycle is shorter and takes less power. The CISC architecture is based on fewer, more complex instructions, which can finish the requested instructions in fewer cycles, but each instruction takes more time and power to be processed.

Let us take a look at both RISC and CISC, and learn more about instructions cycles and registers.

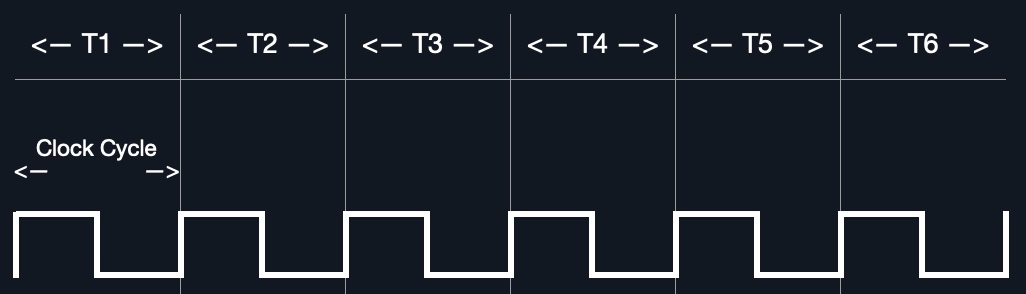

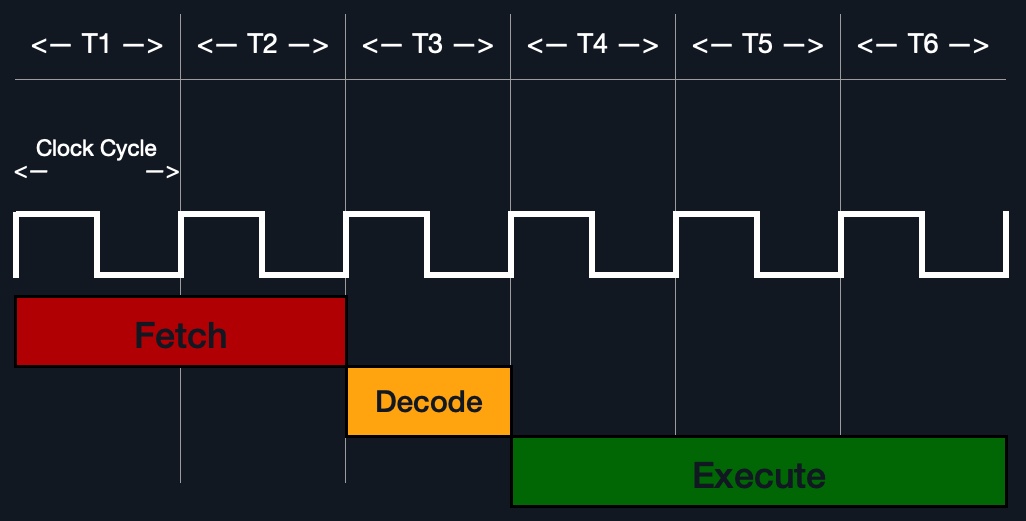

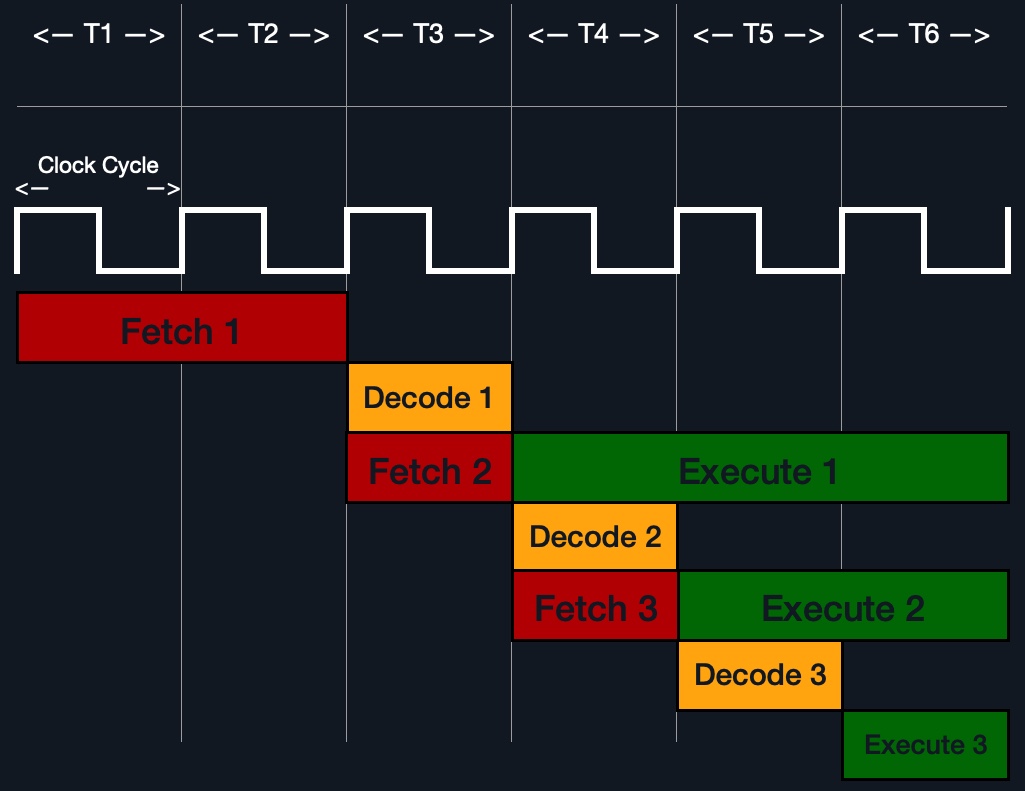

Each CPU has a clock speed that indicates its overall speed. Every tick of the clock runs a clock cycle that processes a basic instruction, such as fetching an address or storing an address. Specifically, this is done by the CU or ALU.

The frequency in which the cycles occur is counted is cycles per second (Hertz). If a CPU has a speed of 3.0 GHz, it can run 3 billion cycles every second (per core).

Modern processors have a multi-core design, allowing them to have multiple cycles at the same time.

An Instruction Cycle is the cycle it takes the CPU to process a single machine instruction.

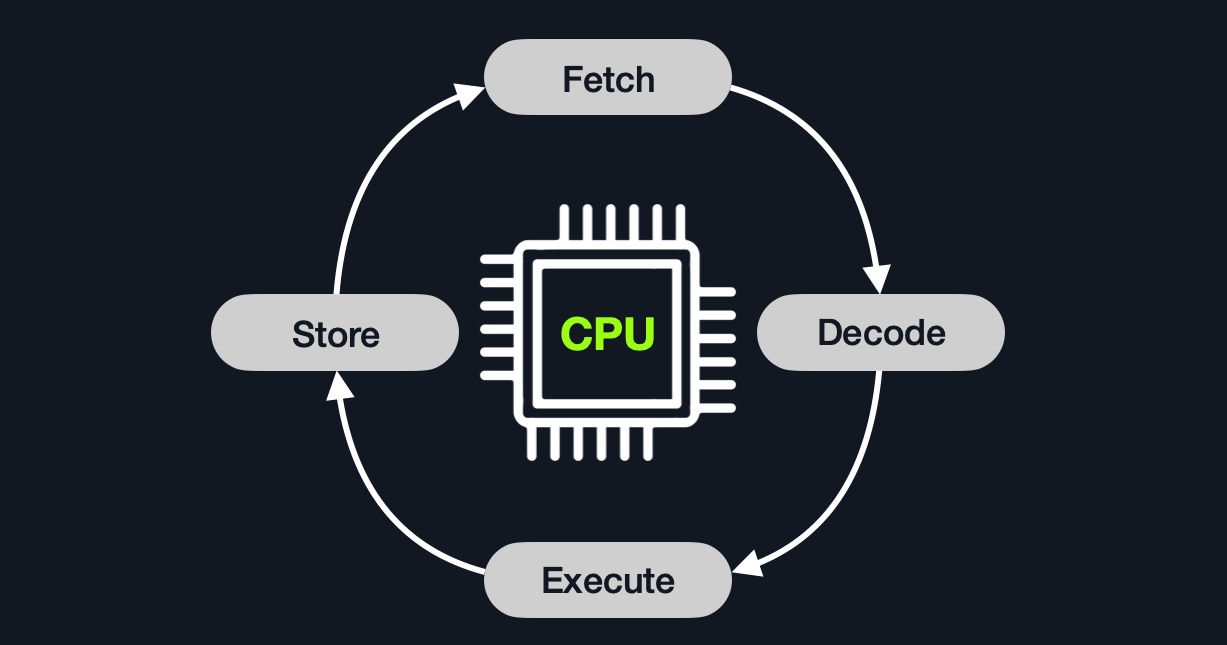

An instruction cycle consists of four stages: Fetch, Decode, Execute, and Store:

| Instruction | Description |

|---|---|

1. Fetch |

Takes the next instruction's address from the Instruction Address Register (IAR), which tells it where the next instruction is located. |

2. Decode |

Takes the instruction from the IAR, and decodes it from binary to see what is required to be executed. |

3. Execute |

Fetch instruction operands from register/memory, and process the instruction in the ALU or CU. |

4. Store |

Store the new value in the destination operand. |

All of the stages in the instruction cycle are carried out by the Control Unit, except when arithmetic instructions need to be executed "add, sub, ..etc", which are executed by the ALU.

Each Instruction Cycle takes multiple clock cycles to finish, depending on the CPU architecture and the complexity of the instruction. Once a single instruction cycle ends, the CU increments to the next instruction and runs the same cycle on it, and so on.

For example, if we were to execute the assembly instruction add rax, 1, it would run through an instruction cycle:

rip register, 48 83 C0 01 (in binary).48 83 C0 01' to know it needs to perform an add of 1 to the value at rax.rax (by CU), add 1 to it (by the ALU).rax.In the past, processors used to process instructions sequentially, so they had to wait for one instruction to finish to start the next. On the other hand, modern processors can process multiple instructions in parallel by having multiple instruction/clock cycles running at the same time. This is made possible by having a multi-thread and multi-core design.

As previously mentioned, each processor understands a different set of instructions. For example, while an Intel processor based on the 64-bit x86 architecture may interpret the machine code 4883C001 as add rax, 1, an ARM processor translates the same machine code as the biceq r8, r0, r8, asr #6 instruction. As we can see, the same machine code performs an entirely different instruction on each processor.

This is because each processor type has a different low-level assembly language architecture known as Instruction Set Architectures (ISA). For example, the add instruction seen above, add rax, 1 is for Intel x86 64-bit processors. The same instruction written for the ARM processor assembly language is represented as add r1, r1, 1.

It is important to understand that each processor has its own set of instructions and corresponding machine code.

Furthermore, a single Instruction Set Architecture may have several syntax interpretations for the same assembly code. For example, the above add instruction is based on the x86 architecture, which is supported by multiple processors like Intel, AMD, and legacy AT\&T processors. The instruction is written as add rax, 1 with Intel syntax, and written as addb $0x1,%rax with AT\&T syntax.

As we can see, even though we can tell that both instructions are similar and do the same thing, their syntax is different, and the locations of the source and destination operands are swapped as well. Still, both codes assemble the same machine code and perform the same instruction.

So, each processor type has its Instruction Set Architectures, and each architecture can be further represented in several syntax formats

This module will focus mainly on the Intel x86 64-bit assembly language (also known as x86_64 and AMD64), as the majority of modern computers and servers run on this processor architecture. We will be using the Intel syntax as well.

If we want to know whether our Linux system supports x86_64 architecture, we can use the lscpu command:

CPU Architecture

root@htb[/htb]$ lscpu

Architecture: x86_64

CPU op-mode(s): 32-bit, 64-bit

Byte Order: Little Endian

<SNIP>

As we can see in the above output, the CPU architecture is x86_64, and supports 32-bit and 64-bit. The byte order is Little Endian. We can also use the uname -m command to get the CPU architecture. We will discuss the two most common Instruction Set Architectures in the next section: CISC and RISC.

An Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) specifies the syntax and semantics of the assembly language on each architecture. It is not just a different syntax but is built in the core design of a processor, as it affects the way and order instructions are executed and their level of complexity. ISA mainly consists of the following components:

| Component | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

Instructions |

The instruction to be processed in the opcode operand_list format. There are usually 1,2, or 3 comma-separated operands. |

add rax, 1, mov rsp, rax, push rax |

Registers |

Used to store operands, addresses, or instructions temporarily. | rax, rsp, rip |

Memory Addresses |

The address in which data or instructions are stored. May point to memory or registers. | 0xffffffffaa8a25ff, 0x44d0, $rax |

Data Types |

The type of stored data. | byte, word, double word |

These are the main components that distinguish different ISA's and assembly languages. We will cover each of them in more depth in the coming sections, and we'll learn how to use various instructions.

There are two main Instruction Set Architectures that are widely used:

Complex Instruction Set Computer (CISC) - Used in Intel and AMD processors in most computers and servers.Reduced Instruction Set Computer (RISC) - Used in ARM and Apple processors, in most smartphones, and some modern laptops.Let us see the pros and cons of each and the main differences between them.

The CISC architecture was one of the earliest ISA's ever developed. As its name suggests, the CISC architecture favors more complex instructions to be run at a time to reduce the overall number of instructions. This is done to rely as much as possible on the CPU by combining minor instructions into more complex instructions.

For example, suppose we were to add two registers with the 'add rax, rbx' instruction. In that case, a CISC processor can do this in a single 'Fetch-Decode-Execute-Store' instruction cycle, without having to split it into multiple instructions to fetch rax, then fetch rbx, then add them, and then store them in `rax, each of which would take its own 'Fetch-Decode-Execute-Store' instruction cycle.

Two main reasons drove this:

To enable the processors to execute complex instructions, the processor's design becomes more complicated, as it is designed to execute a vast amount of different complex instructions, each of which has its own unit to execute it.

Furthermore, even though it takes a single instruction cycle to execute a single instruction, as the instructions are more complex, each instruction cycle takes more clock cycles. This fact leads to more power consumption and heat to execute each instruction.

The RISC architecture favors splitting instructions into minor instructions, and so the CPU is designed only to handle simple instructions. This is done to relay the optimization to the software by writing the most optimized assembly code.

For example, the same previous add r1, r2, r3 instruction on a RISC processor would fetch r2, then fetch r3, add them, and finally store them in r1. Every instruction of these takes an entire 'Fetch-Decode-Execute-Store' instruction cycle, which leads, as can be expected, to a larger number of total instructions per program, and hence a longer assembly code.

By not supporting various types of complex instructions, RISC processors only support a limited number of instructions (~200) compared to CISC processors (~1500). So, to execute complex instructions, this has to be done through a combination of minor instructions through Assembly.

It is said that we can build a general-purpose computer with a processor that only supports one instruction! This indicates that we can create very complex instructions using the sub instruction only. Can you think of how this may be achieved?

On the other hand, an advantage of splitting complex instructions into minor ones is having all instructions of the same length either 32-bit or 64-bit long. This enables designing the CPU clock speed around the instruction length so that executing each stage in the instruction cycle would always take precisely one machine clock cycle.

The below diagram shows how CISC instructions take a variable amount of clock cycles, while RISC instructions take a fixed amount:

Executing each instruction stage in a single clock cycle and only executing simple instructions leads to RISC processors consuming a fraction of the power consumed by CISC processors, which makes these processors ideal for devices that run on batteries, like smartphones and laptops.

The following table summarizes the main differences between CISC and RISC:

| Area | CISC | RISC |

|---|---|---|

Complexity |

Favors complex instructions | Favors simple instructions |

Length of instructions |

Longer instructions - Variable length 'multiples of 8-bits' | Shorter instructions - Fixed length '32-bit/64-bit' |

Total instructions per program |

Fewer total instructions - Shorter code | More total instructions - Longer code |

Optimization |

Relies on hardware optimization (in CPU) | Relies on software optimization (in Assembly) |

Instruction Execution Time |

Variable - Multiple clock cycles | Fixed - One clock cycle |

Instructions supported by CPU |

Many instructions (~1500) | Fewer instructions (~200) |

Power Consumption |

High | Very low |

Examples |

Intel, AMD | ARM, Apple |

In the past, having a longer assembly code due to a larger number of total instructions per program was a significant disadvantage for RISC processors due to the limited resources in memory and storage. However, today this is no longer as big of an issue, as memory and storage are not as expensive and limited as they used to be in the past.

Furthermore, with new assemblers and compilers writing extremely optimized code on the software level, RISC processors are becoming faster than CISC processors, even in executing and processing heavy applications, all while consuming much less power.

All of this is making RISC processors more common in recent years. RISC may become the dominant architecture in the upcoming years. But as we speak, the overwhelming majority of computers and servers we will be pentesting are running on Intel/AMD processors with the CISC architecture, making learning CISC assembly our priority. As the basics of all Assembly language variants are pretty similar, learning ARM Assembly should be more straightforward after completing this module.

Now that we understand general computer and processor architecture, we need to understand a few assembly elements before we start learning Assembly: Registers, Memory Addresses, Address Endianness, and Data Types. Each of these elements is important, and properly understanding them will help us avoid issues and hours of troubleshooting while writing and debugging assembly code.

As previously mentioned, each CPU core has a set of registers. The registers are the fastest components in any computer, as they are built within the CPU core. However, registers are very limited in size and can only hold a few bytes of data at a time. There are many registers in the x86 architecture, but we will only focus on the ones necessary for learning basic Assembly and essential for future binary exploitation.

There are two main types of registers we will be focusing on: Data Registers and Pointer Registers.

| Data Registers | Pointer Registers |

|---|---|

rax |

rbp |

rbx |

rsp |

rcx |

rip |

rdx |

|

r8 |

|

r9 |

|

r10 |

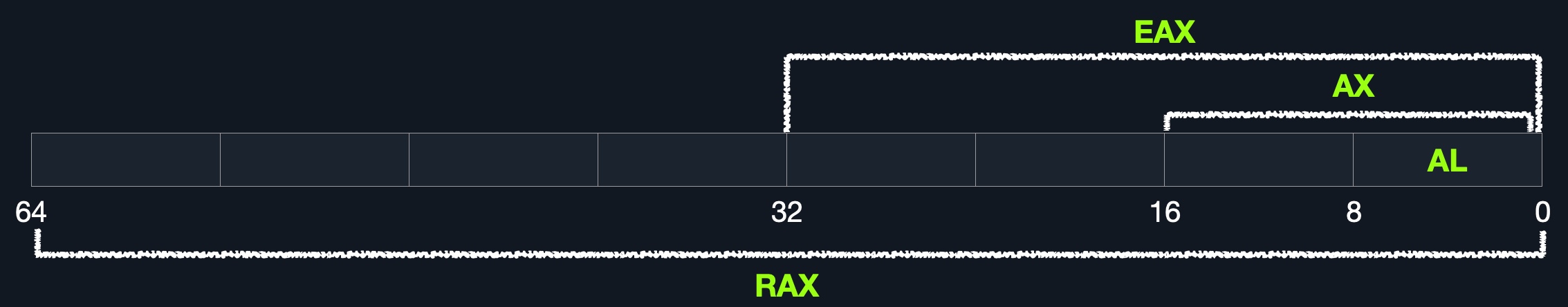

Data Registers - are usually used for storing instructions/syscall arguments. The primary data registers are: rax, rbx, rcx, and rdx. The rdi and rsi registers also exist and are usually used for the instruction destination and source operands. Then, we have secondary data registers that can be used when all previous registers are in use, which are r8, r9, and r10.Pointer Registers - are used to store specific important address pointers. The main pointer registers are the Base Stack Pointer rbp, which points to the beginning of the Stack, the Current Stack Pointer rsp, which points to the current location within the Stack (top of the Stack), and the Instruction Pointer rip, which holds the address of the next instruction.Each 64-bit register can be further divided into smaller sub-registers containing the lower bits, at one byte 8-bits, 2 bytes 16-bits, and 4 bytes 32-bits. Each sub-register can be used and accessed on its own, so we don't have to consume the full 64-bits if we have a smaller amount of data.

Sub-registers can be accessed as:

| Size in bits | Size in bytes | Name | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

16-bit |

2 bytes |

the base name | ax |

8-bit |

1 bytes |

base name and/or ends with l |

al |

32-bit |

4 bytes |

base name + starts with the e prefix |

eax |

64-bit |

8 bytes |

base name + starts with the r prefix |

rax |

For example, for the bx data register, the 16-bit is bx, so the 8-bit is bl, the 32-bit would be ebx, and the 64-bit would be rbx. The same goes for pointer registers. If we take the base stack pointer bp, its 16-bit sub-register is bp, so the 8-bit is bpl, the 32-bit is ebp, and the 64-bit is rbp.

The following are the names of the sub-registers for all of the essential registers in an x86_64 architecture:

| Description | 64-bit Register | 32-bit Register | 16-bit Register | 8-bit Register |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data/Arguments Registers | ||||

| Syscall Number/Return value | rax |

eax |

ax |

al |

| Callee Saved | rbx |

ebx |

bx |

bl |

| 1st arg - Destination operand | rdi |

edi |

di |

dil |

| 2nd arg - Source operand | rsi |

esi |

si |

sil |

| 3rd arg | rdx |

edx |

dx |

dl |

| 4th arg - Loop counter | rcx |

ecx |

cx |

cl |

| 5th arg | r8 |

r8d |

r8w |

r8b |

| 6th arg | r9 |

r9d |

r9w |

r9b |

| Pointer Registers | ||||

| Base Stack Pointer | rbp |

ebp |

bp |

bpl |

| Current/Top Stack Pointer | rsp |

esp |

sp |

spl |

| Instruction Pointer 'call only' | rip |

eip |

ip |

ipl |

As we go through the module, we'll discuss how to use each of these registers.

There are other various registers, but we will not cover them in this module, as they are not needed for basic Assembly usage. As an example, there's the RFLAGS register, which is used to maintain various flags used by the CPU, like the zero flag ZF, which is used for conditional instructions.

As previously mentioned, x86 64-bit processors have 64-bit wide addresses that range from 0x0 to 0xffffffffffffffff, so we expect the addresses to be in this range. However, RAM is segmented into various regions, like the Stack, the heap, and other program and kernel-specific regions. Each memory region has specific read, write, execute permissions that specify whether we can read from it, write to it, or call an address in it.

Whenever an instruction goes through the Instruction Cycle to be executed, the first step is to fetch the instruction from the address it's located at, as previously discussed. There are several types of address fetching (i.e., addressing modes) in the x86 architecture:

| Addressing Mode | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

Immediate |

The value is given within the instruction | add 2 |

Register |

The register name that holds the value is given in the instruction | add rax |

Direct |

The direct full address is given in the instruction | call 0xffffffffaa8a25ff |

Indirect |

A reference pointer is given in the instruction | call 0x44d000 or call [rax] |

Stack |

Address is on top of the stack | add rsp |

In the above table, lower is slower. The less immediate the value is, the slower it is to fetch it.

Even though speed isn't our biggest concern when learning basic Assembly, we should understand where and how each address is located. Having this understanding will help us in future binary exploitation, with Buffer Overflow exploits, for example. The same understanding will have an even more significant implication with advanced binary exploitation, like ROP or Heap exploitation.

An address endianness is the order of its bytes in which they are stored or retrieved from memory. There are two types of endianness: Little-Endian and Big-Endian. With Little-Endian processors, the little-end byte of the address is filled/retrieved first right-to-left, while with Big-Endian processors, the big-end byte is filled/retrieved first left-to-right.

For example, if we have the address 0x0011223344556677 to be stored in memory, little-endian processors would store the 0x00 byte on the right-most bytes, and then the 0x11 byte would be filled after it, so it becomes 0x1100, and then the 0x22 byte, so it becomes 0x221100, and so on. Once all bytes are in place, they would look like 0x7766554433221100, which is the reverse of the original value. Of course, when retrieving the value back, the processor will also use little-endian retrieval, so the value retrieved would be the same as the original value.

Another example that shows how this can affect the stored values is binary. For example, if we had the 2-byte integer 426, its binary representation is 00000001 10101010. The order in which these two bytes are stored would change its value. For example, if we stored it in reverse as 10101010 00000001, its value becomes 43521.

The big-endian processors would store these bytes as 00000001 10101010 left-to-right, while little-endian processors store them as 10101010 00000001 right-to-left. When retrieving the value, the processor has to use the same endianness used when storing them, or it will get the wrong value. This indicates that the order in which the bytes are stored/retrieved makes a big difference.

The following table demonstrates how endianness works:

| Address | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Address Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little Endian | 77 | 66 | 55 | 44 | 33 | 22 | 11 | 00 | 0x |

| Big Endian | 00 | 11 | 22 | 33 | 44 | 55 | 66 | 77 | 0x |

Address: 0x0011223344556677

Load Address\

You can click on the "Load Address" button to visualize how each endianness loads data/addresses into memory.

As we can see, this means that an address written in little-endian or in big-endian would refer to different locations in the memory, as it would be read differently by each processor type.

This module will always use little-endian byte order, as it is used with Intel/AMD x86 in most modern operating systems, so the shellcode is always represented right-to-left.

The important thing we need to take from this is knowing that our bytes are stored into memory from right-to-left. So, if we were to push an address or a string with Assembly, we would have to push it in reverse. For example, if we want to store the word Hello, we would push its bytes in reverse: o, l, l, e, and finally H.

This may seem a bit counter-intuitive since most people are used to reading from left-to-right. However, this has multiple advantages when processing data, like being able to retrieve a sub-register without having to go through the entire register or being able to perform arithmetic in the correct order right-to-left.

Finally, the x86 architecture supports many types of data sizes, which can be used with various instructions. The following are the most common data types we will be using with instructions:

| Component | Length | Example |

|---|---|---|

byte |

8 bits | 0xab |

word |

16 bits - 2 bytes | 0xabcd |

double word (dword) |

32 bits - 4 bytes | 0xabcdef12 |

quad word (qword) |

64 bits - 8 bytes | 0xabcdef1234567890 |

Whenever we use a variable with a certain data type or use a data type with an instruction, both operands should be of the same size.

For example, we can't use a variable defined as byte with rax, as rax has a size of 8 bytes. In this case, we would have to use al, which has the same size of 1 byte. The following table shows the appropriate data type for each sub-register:

| Sub-register | Data Type |

|---|---|

al |

byte |

ax |

word |

eax |

dword |

rax |

qword |

We will discuss this further in the upcoming sections. With all fundamentals of Assembly covered, we can start learning about x86 assembly instructions and writing basic Assembly code.

As we learn various Assembly instructions in the coming sections, we'll constantly be writing code, assembling it, and debugging it. This is the best way to learn what each instruction does. So, we need to learn the basic structure of an Assembly code file and then assemble it and debug it.

In this section, we'll go through the basic structure of an Assembly file, and in the following two sections, we will cover assembling it and debugging it. We will be working on a template Hello World! Assembly code as a sample, to first learn the general structure of an assembly file and then how to assemble it and debug it. Let us start by taking a look at and dissecting a sample Hello World! Assembly code template:

Code: nasm

global _start

section .data

message: db "Hello HTB Academy!"

section .text

_start:

mov rax, 1

mov rdi, 1

mov rsi, message

mov rdx, 18

syscall

mov rax, 60

mov rdi, 0

syscall

This Assembly code (once assembled and linked) should print the string 'Hello HTB Academy!' to the screen. We won't go into detail on how this is processed just yet, but we need to understand the main elements of the code template.

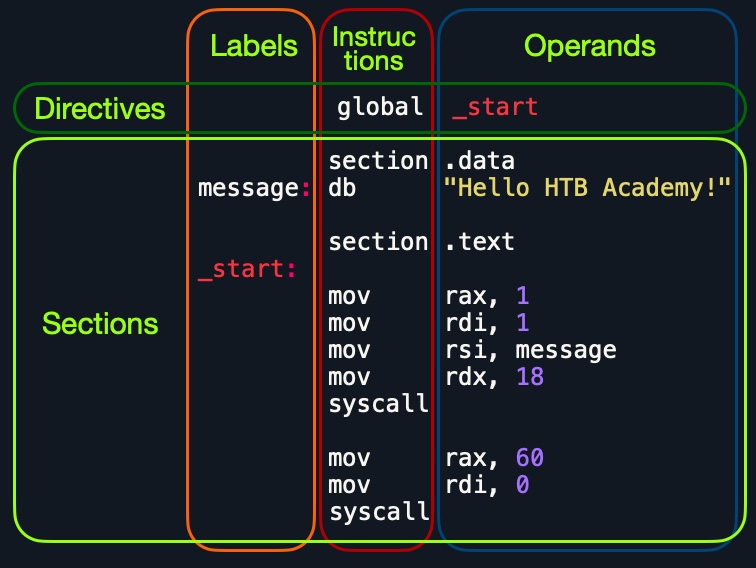

First, let's examine the way the code is distributed:

Looking at the vertical parts of the code, each line can have three elements:

1. Labels |

2. Instructions |

3. Operands |

|---|---|---|

We have discussed the instructions and their operands in the previous sections, and we'll go into detail on various assembly instructions in the coming sections. In addition to that, we can define a label at each line. Each label can be referred to by instructions or by directives.

Next, if we look at the code line-by-line, we see that it has three main parts:

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

global _start |

This is a directive that directs the code to start executing at the _start label defined below. |

section .data |

This is the data section, which should contain all of the variables. |

section .text |

This is the text section containing all of the code to be executed. |

Both the .data and .text sections refer to the data and text memory segments, in which these instructions will be stored.

An Assembly code is line-based, which means that the file is processed line-by-line, executing the instruction of each line. We see at the first line a directive global _start, which instructs the machine to start processing the instructions after the _start label. So, the machine goes to the _start label and starts executing the instructions there, which will print the message on the screen. This will be covered more thoroughly in the Control Instructions sections.

Next, we have the .data section. The data section holds our variables to make it easier for us to define variables and reuse them without writing them multiple times. Once we run our program, all of our variables will be loaded into memory in the data segment.

When we run the program, it will load any variables we have defined into memory so that they will be ready for usage when we call them. We will notice later in the module that by the time we start executing instructions at the _start label, all of our variables will be already loaded into memory.

We can define variables using db for a list of bytes, dw for a list of words, dd for a list of digits, and so on. We can also label any of our variables so we can call it or reference it later. The following are some examples of defining variables:

| Instruction | Description |

|---|---|

db 0x0a |

Defines the byte 0x0a, which is a new line. |

message db 0x41, 0x42, 0x43, 0x0a |

Defines the label message => abc. |

message db "Hello World!", 0x0a |

Defines the label message => Hello World!. |

Furthermore, we can use the equ instruction with the $ token to evaluate an expression, like the length of a defined variable's string. However, the labels defined with the equ instruction are constants, and they cannot be changed later.

For example, the following code defines a variable and then defines a constant for its length:

Code: nasm

section .data

message db "Hello World!", 0x0a

length equ $-message

Note: the $ token indicates the current distance from the beginning of the current section. As the message variable is at the beginning of the data section, the current location, i.e,. value of $, equals the length of the string. For the scope of this module, we will only use this token to calculate lengths of strings, using the same line of code shown above.

The second (and most important) section is the .text section. This section holds all of the assembly instructions and loads them to the text memory segment. Once all instructions are loaded into the text segment, the processor starts executing them one after another.

The default convention is to have the _start label at the beginning of the .text section, which -as per the global _start directive- starts the main code that will be executed as the program runs. As we will see later in the module, we can define other labels within the .text section, for loops and other functions.

The text segment within the memory is read-only, so we cannot write any variables within it. The data section, on the other hand, is read/write, which is why we write our variables to it. However, the data segment within the memory is not executable, so any code we write to it cannot be executed. This separation is part of memory protections to mitigate things like buffer overflows and other types of binary exploitation.

Tip: We can add comments to our assembly code with a semi-colon ;. We can use comments to explain the purpose of each part of the code, and what each line is doing. Doing so will save us a lot of time in the future if we ever revisit the code and need to understand it.

With this, we should understand the basic structure of an Assembly file.

Now that we understand the basic structure and elements of an Assembly file, we can start assembling it using the nasm tool. The entire assembly file structure we learned in the previous section is based on the nasm file structure. Upon assembling our code with nasm, it understands the various parts of the file and then correctly assembles them to be properly run during run time.

After we assemble our code with nasm, we can link it using ld to utilize various OS features and libraries.

First, we will copy the code below into a file called helloWorld.s.

Note: assembly files usually use the .s or the .asm extensions. We will be using .s in this module.

We don't have to keep using tabs to separate parts of an assembly file, as this was only for demonstration purposes. We can write the following code into our helloWorld.s file:

Code: nasm

global _start

section .data

message db "Hello HTB Academy!"

length equ $-message

section .text

_start:

mov rax, 1

mov rdi, 1

mov rsi, message

mov rdx, length

syscall

mov rax, 60

mov rdi, 0

syscall

Note how we used equ to dynamically calculate the length of message, instead of using a static 18. This will become very handy later on. Once we do, we will assemble the file using nasm, with the following command:

Assembling & Disassembling

root@htb[/htb]$ nasm -f elf64 helloWorld.s

Note: The -f elf64 flag is used to note that we want to assemble a 64-bit assembly code. If we wanted to assemble a 32-bit code, we would use -f elf.

This should output a helloWorld.o object file, which is then assembled into machine code, along with the details of all variables and sections. This file is not executable just yet.

The final step is to link our file using ld. The helloWorld.o object file, though assembled, still cannot be executed. This is because many references and labels used by nasm need to be resolved into actual addresses, along with linking the file with various OS libraries that may be needed.

This is why a Linux binary is called ELF, which stands for an Executable and Linkable Format. To link a file using ld, we can use the following command:

Assembling & Disassembling

root@htb[/htb]$ ld -o helloWorld helloWorld.o

Note: if we were to assemble a 32-bit binary, we need to add the '-m elf_i386' flag.

Once we link the file with ld, we should have the final executable file:

Assembling & Disassembling

root@htb[/htb]$ ./helloWorld

Hello HTB Academy!

We have successfully assembled and linked our first assembly file. We will be assembling, linking, and running our code frequently through this module, so let us build a simple bash script to make it easier:

Code: bash

#!/bin/bash

fileName="${1%%.*}" # remove .s extension

nasm -f elf64 ${fileName}".s"

ld ${fileName}".o" -o ${fileName}

[ "$2" == "-g" ] && gdb -q ${fileName} || ./${fileName}

Now we can write this script to assembler.sh, chmod +x it, and then run it on our assembly file. It will assemble it, link it, and run it:

Assembling & Disassembling

root@htb[/htb]$ ./assembler.sh helloWorld.s

Hello HTB Academy!

Great! Before we move on, let's disassemble and examine our files to learn more about the process we just did.

To disassemble a file, we will use the objdump tool, which dumps machine code from a file and interprets the assembly instruction of each hex code. We can disassemble a binary using the -D flag.

Note: we will also use the flag -M intel, so that objdump would write the instructions in the Intel syntax, which we are using, as we discussed before.

Let's start by disassembling our final ELF executable file:

Assembling & Disassembling

root@htb[/htb]$ objdump -M intel -d helloWorld

helloWorld: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000401000 <_start>:

401000: b8 01 00 00 00 mov eax,0x1

401005: bf 01 00 00 00 mov edi,0x1

40100a: 48 be 00 20 40 00 00 movabs rsi,0x402000

401011: 00 00 00

401014: ba 12 00 00 00 mov edx,0x12

401019: 0f 05 syscall

40101b: b8 3c 00 00 00 mov eax,0x3c

401020: bf 00 00 00 00 mov edi,0x0

401025: 0f 05 syscall

We see that our original assembly code is highly preserved, with the only change being 0x402000 used in place of the message variable and replacing the length constant with its value of 0x12. We also see that nasm efficiently changed our 64-bit registers to the 32-bit sub-registers where possible, to use less memory when possible, like changing mov rax, 1 to mov eax,0x1.

If we wanted to only show the assembly code, without machine code or addresses, we could add the --no-show-raw-insn --no-addresses flags, as follows:

Assembling & Disassembling

root@htb[/htb]$ objdump -M intel --no-show-raw-insn --no-addresses -d helloWorld

helloWorld: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .text:

<_start>:

mov eax,0x1

mov edi,0x1

movabs rsi,0x402000

mov edx,0x12

syscall

mov eax,0x3c

mov edi,0x0

syscall

Note: Note that objdump has changed the third instruction into movabs. This is the same as mov, so in case you need to reassemble the code, you can change it back to mov.

The -d flag will only disassemble the .text section of our code. To dump any strings, we can use the -s flag, and add -j .data to only examine the .data section. This means that we also do not need to add -M intel. The final command is as follows:

Assembling & Disassembling

root@htb[/htb]$ objdump -sj .data helloWorld

helloWorld: file format elf64-x86-64

Contents of section .data:

402000 48656c6c 6f204854 42204163 6164656d Hello HTB Academ

402010 7921 y!

As we can see, the .data section indeed contains the message variable with the string Hello HTB Academy!. This should give us a better idea of how our code was assembled into machine code and how it looks after we assemble it. Next, let us go through the basics of code debugging, which is a critical skill we need to learn.

Debugging is an important skill to learn for developers and pentesters alike. Debugging is a term used for finding and removing issues (i.e., bugs) from our code, hence the name de-bugging. When we develop a program, we will very frequently run into bugs in our code. It is not efficient to keep changing our code until it does what we expect of it. Instead, we perform debugging by setting breakpoints and seeing how our program acts on each of them and how our input changes between them, which should give us a clear idea of what is causing the bug.

Programs written in high-level languages can set breakpoints on specific lines and run the program through a debugger to monitor how they act. With Assembly, we deal with machine code represented as assembly instructions, so our breakpoints are set in the memory location in which our machine code is loaded, as we will see.

To debug our binaries, we will be using a well-known debugger for Linux programs called GNU Debugger (GDB). There are other similar debuggers for Linux, like Radare and Hopper, and for Windows, like Immunity Debugger and WinGDB. There are also powerful debuggers available for many platforms, like IDA Pro and EDB. In this module, we will be using GDB. It is the most reliable for Linux binaries since it is built and maintained directly by GNU, which gives it an excellent integration with the Linux system and its components.

GDB is installed in many Linux distributions, and it is also installed by default in Parrot OS and PwnBox. In case it is not installed in your VM, you can use apt to install it with the following commands:

GNU Debugger (GDB)

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo apt-get update

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo apt-get install gdb

One of the great features of GDB is its support for third-party plugins. An excellent plugin that is well maintained and has good documentation is GEF. GEF is a free and open-source GDB plugin that is built precisely for reverse engineering and binary exploitation. This fact makes it a great tool to learn.

To add GEF to GDB, we can use the following commands:

GNU Debugger (GDB)

root@htb[/htb]$ wget -O ~/.gdbinit-gef.py -q https://gef.blah.cat/py

root@htb[/htb]$ echo source ~/.gdbinit-gef.py >> ~/.gdbinit

Now that we have both tools installed, we can run gdb to debug our HelloWorld binary using the following commands, and GEF will be loaded automatically:

GNU Debugger (GDB)

root@htb[/htb]$ gdb -q ./helloWorld

...SNIP...

gef➤

As we can see from gef➤, GEF is loaded when GDB is run. If you ever run into any issues with GEF, you can consult with the GEF Documentation, and you will likely find a solution.

Going forward, we will frequently be assembling and linking our assembly code and then running it with gdb. To do so quickly, we can use the assembler.sh script we wrote in the previous section with the -g flag. It will assemble and link the code, and then run it with gdb, as follows:

GNU Debugger (GDB)

root@htb[/htb]$ ./assembler.sh helloWorld.s -g

...SNIP...

gef➤

Once GDB is started, we can use the info command to view general information about the program, like its functions or variables.

Tip: If we want to understand how any command runs within GDB, we can use the help CMD command to get its documentation. For example, we can try executing help info

Functions

To start, we will use the info command to check which functions are defined within the binary:

GNU Debugger (GDB)

gef➤ info functions

All defined functions:

Non-debugging symbols:

0x0000000000401000 _start

As we can see, we found our main _start function.

Variables

We can also use the info variables command to view all available variables within the program:

GNU Debugger (GDB)

gef➤ info variables

All defined variables:

Non-debugging symbols:

0x0000000000402000 message

0x0000000000402012 __bss_start

0x0000000000402012 _edata

0x0000000000402018 _end

As we can see, we find the message, along with some other default variables that define memory segments. We can do many things with functions, but we will focus on two main points: Disassembly and Breakpoints.

To view the instructions within a specific function, we can use the disassemble or disas command along with the function name, as follows:

GNU Debugger (GDB)

gef➤ disas _start

Dump of assembler code for function _start:

0x0000000000401000 <+0>: mov eax,0x1

0x0000000000401005 <+5>: mov edi,0x1

0x000000000040100a <+10>: movabs rsi,0x402000

0x0000000000401014 <+20>: mov edx,0x12

0x0000000000401019 <+25>: syscall

0x000000000040101b <+27>: mov eax,0x3c

0x0000000000401020 <+32>: mov edi,0x0

0x0000000000401025 <+37>: syscall

End of assembler dump.

As we can see, the output we got closely resembles our assembly code and the disassembly output we got from objdump in the previous section. We need to focus on the main thing from this disassembly: the memory addresses for each instruction and operands (i.e., arguments).

Having the memory address is critical for examining the variables/operands and setting breakpoints for a certain instruction.

You may notice through debugging that some memory addresses are in the form of 0x00000000004xxxxx, rather than their raw address in memory 0xffffffffaa8a25ff. This is due to $rip-relative addressing in Position-Independent Executables PIE, in which the memory addresses are used relative to their distance from the instruction pointer $rip within the program's own Virtual RAM, rather than using raw memory addresses. This feature may be disabled to reduce the risk of binary exploitation.

Next, let us go through the basics of debugging with GDB by using breakpoints, examining data, and stepping through the program.

Now that we have the general information about our program, we will start running it and debugging it. Debugging consists mainly of four steps:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

Break |

Setting breakpoints at various points of interest |

Examine |

Running the program and examining the state of the program at these points |

Step |

Moving through the program to examine how it acts with each instruction and with user input |

Modify |

Modify values in specific registers or addresses at specific breakpoints, to study how it would affect the execution |

We will go through these points in this section to learn the basics of debugging a program with GDB.

The first step of debugging is setting breakpoints to stop the execution at a specific location or when a particular condition is met. This helps us in examining the state of the program and the value of registers at that point. Breakpoints also allow us to stop the program's execution at that point so that we can step into each instruction and examine how it changes the program and values.

We can set a breakpoint at a specific address or for a particular function. To set a breakpoint, we can use the break or b command along with the address or function name we want to break at. For example, to follow all instructions run by our program, let's break at the _start function, as follows:

Debugging with GDB

gef➤ b _start

Breakpoint 1 at 0x401000

Now, in order to start our program, we can use the run or r command:

gef➤ b _start

Breakpoint 1 at 0x401000

gef➤ r

Starting program: ./helloWorld

Breakpoint 1, 0x0000000000401000 in _start ()

[ Legend: Modified register | Code | Heap | Stack | String ]

───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── registers ────

$rax : 0x0

$rbx : 0x0

$rcx : 0x0

$rdx : 0x0

$rsp : 0x00007fffffffe310 → 0x0000000000000001

$rbp : 0x0

$rsi : 0x0

$rdi : 0x0

$rip : 0x0000000000401000 → <_start+0> mov eax, 0x1

...SNIP...

───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── stack ────

0x00007fffffffe310│+0x0000: 0x0000000000000001 ← $rsp

0x00007fffffffe318│+0x0008: 0x00007fffffffe5a0 → "./helloWorld"

...SNIP...

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── code:x86:64 ────

0x400ffa add BYTE PTR [rax], al

0x400ffc add BYTE PTR [rax], al

0x400ffe add BYTE PTR [rax], al

→ 0x401000 <_start+0> mov eax, 0x1

0x401005 <_start+5> mov edi, 0x1

0x40100a <_start+10> movabs rsi, 0x402000

0x401014 <_start+20> mov edx, 0x12

0x401019 <_start+25> syscall

0x40101b <_start+27> mov eax, 0x3c

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── threads ────

[#0] Id 1, Name: "helloWorld", stopped 0x401000 in _start (), reason: BREAKPOINT

───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── trace ────

[#0] 0x401000 → _start()

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

If we want to set a breakpoint at a certain address, like _start+10, we can either b *_start+10 or b *0x40100a:

Debugging with GDB

gef➤ b *0x40100a

Breakpoint 1 at 0x40100a

The * tells GDB to break at the instruction stored in 0x40100a.

Note: Once the program is running, if we set another breakpoint, like b *0x401005, in order to continue to that breakpoint, we should use the continue or c command. If we use run or r again, it will run the program from the start. This can be useful to skip loops, as we will see later in the module.

If we want to see what breakpoints we have at any point of the execution, we can use the info breakpoint command. We can also disable, enable, or delete any breakpoint. Furthermore, GDB also supports setting conditional breaks that stop the execution when a specific condition is met.

The next step of debugging is examining the values in registers and addresses. As we can see in the previous terminal output, GEF automatically gave us a lot of helpful information when we hit our breakpoint. This is one of the benefits of having the GEF plugin, as it automates many steps that we usually take at every breakpoint, like examining the registers, the stack, and the current assembly instructions.

To manually examine any of the addresses or registers or examine any other, we can use the x command in the format of x/FMT ADDRESS, as help x would tell us. The ADDRESS is the address or register we want to examine, while FMT is the examine format. The examine format FMT can have three parts:

| Argument | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

Count |

The number of times we want to repeat the examine | 2, 3, 10 |

Format |

The format we want the result to be represented in | x(hex), s(string), i(instruction) |

Size |

The size of memory we want to examine | b(byte), h(halfword), w(word), g(giant, 8 bytes) |

Instructions

For example, if we wanted to examine the next four instructions in line, we will have to examine the $rip register (which holds the address of the next instruction), and use 4 for the count, i for the format, and g for the size (for 8-bytes or 64-bits). So, the final examine command would be x/4ig $rip, as follows:

Debugging with GDB

gef➤ x/4ig $rip

=> 0x401000 <_start>: mov eax,0x1

0x401005 <_start+5>: mov edi,0x1

0x40100a <_start+10>: movabs rsi,0x402000

0x401014 <_start+20>: mov edx,0x12

We see that we get the following four instructions as expected. This can help us as we go through a program in examining certain areas and what instructions they may contain.

Strings

We can also examine a variable stored at a specific memory address. We know that our message variable is stored at the .data section on address 0x402000 from our previous disassembly. We also see the upcoming command movabs rsi, 0x402000, so we may want to examine what is being moved from 0x402000.

In this case, we will not put anything for the Count, as we only want one address (1 is the default), and will use s as the format to get it in a string format rather than in hex:

Debugging with GDB

gef➤ x/s 0x402000

0x402000: "Hello HTB Academy!"

As we can see, we can see the string at this address represented as text rather than hex characters.

Note: if we don't specify the Size or Format, it will default to the last one we used.

Addresses

The most common format of examining is hex x. We often need to examine addresses and registers containing hex data, such as memory addresses, instructions, or binary data. Let us examine the same previous instruction, but in hex format, to see how it looks:

Debugging with GDB

gef➤ x/wx 0x401000

0x401000 <_start>: 0x000001b8

We see instead of mov eax,0x1, we get 0x000001b8, which is the hex representation of the mov eax,0x1 machine code in little-endian formatting.

b8 01 00 00.Try repeating the commands we used for examining strings using x to examine them in hex. We should see the same text but in hex format. We can also use GEF features to examine certain addresses. For example, at any point we can use the registers command to print out the current value of all registers:

gdb

gef➤ registers

$rax : 0x0

$rbx : 0x0

$rcx : 0x0

$rdx : 0x0

$rsp : 0x00007fffffffe310 → 0x0000000000000001

$rbp : 0x0

$rsi : 0x0

$rdi : 0x0

$rip : 0x0000000000401000 → <_start+0> mov eax, 0x1

...SNIP...

The third step of debugging is stepping through the program one instruction or line of code at a time. As we can see, we are currently at the very first instruction in our helloWorld program:

gdb

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── code:x86:64 ────

0x400ffe add BYTE PTR [rax], al

→ 0x401000 <_start+0> mov eax, 0x1

0x401005 <_start+5> mov edi, 0x1

Note: the instruction shown with the -> symbol is where we are at, and it has not yet been processed.

To move through the program, there are three different commands we can use: stepi and step.

Step Instruction

The stepi or si command will step through the assembly instructions one by one, which is the smallest level of steps possible while debugging. Let us use the si command to see how we get to the next instruction:

gdb

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── code:x86:64 ────

gef➤ si

0x0000000000401005 in _start ()

0x400fff add BYTE PTR [rax+0x1], bh

→ 0x401005 <_start+5> mov edi, 0x1

0x40100a <_start+10> movabs rsi, 0x402000

0x401014 <_start+20> mov edx, 0x12

0x401019 <_start+25> syscall

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── threads ────

[#0] Id 1, Name: "helloWorld", stopped 0x401005 in _start (), reason: SINGLE STEP

As we can see, we took exactly one step and stopped again at the mov edi, 0x1 instruction.

Step Count

Similarly to examine, we can repeat the si command by adding a number after it. For example, if we wanted to move 3 steps to reach the syscall instruction, we can do so as follows:

gdb

gef➤ si 3

0x0000000000401019 in _start ()

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── code:x86:64 ────

0x401004 <_start+4> add BYTE PTR [rdi+0x1], bh

0x40100a <_start+10> movabs rsi, 0x402000

0x401014 <_start+20> mov edx, 0x12

→ 0x401019 <_start+25> syscall

0x40101b <_start+27> mov eax, 0x3c

0x401020 <_start+32> mov edi, 0x0

0x401025 <_start+37> syscall

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── threads ────

[#0] Id 1, Name: "helloWorld", stopped 0x401019 in _start (), reason: SINGLE STEP

As we can see, we stopped at the syscall instruction as expected.

Tip: You can hit the return/enter empty in order to repeat the last command. Try hitting it at this stage, and you should make another 3 steps, and break at the other syscall instruction.

Step

The step or s command, on the other hand, will continue until the following line of code is reached or until it exits from the current function. If we run an assembly code, it will break when we exit the current function _start.

If there's a call to another function within this function, it'll break at the beginning of that function. Otherwise, it'll break after we exit this function after the program's end. Let us try using s, and see what happens:

Debugging with GDB

gef➤ step

Single stepping until exit from function _start,

which has no line number information.

Hello HTB Academy!

[Inferior 1 (process 14732) exited normally]

We see that the execution continued until we reached the exit from the _start function, so we reached the end of the program and exited normally without any errors. We also see that GDB printed the program's output Hello HTB Academy! as well.

Note: There's also the next or n command, which will also continue until the next line, but will skip any functions called in the same line of code, instead of breaking at them like step. There's also the nexti or ni, which is similar to si, but skips functions calls, as we will see later on in the module.

The final step of debugging is modifying values in registers and addresses at a certain point of execution. This helps us in seeing how this would affect the execution of the program.

Addresses

To modify values in GDB, we can use the set command. However, we will utilize the patch command in GEF to make this step much easier. Let's enter help patch in GDB to get its help menu:

Debugging with GDB

gef➤ help patch

Write specified values to the specified address.

Syntax: patch (qword|dword|word|byte) LOCATION VALUES

patch string LOCATION "double-escaped string"

...SNIP...

As we can see, we have to provide the type/size of the new value, the location to be stored, and the value we want to use. So, let's try changing the string stored in the .data section (at address 0x402000 as we saw earlier) to the string Patched!.

We will break at the first syscall at 0x401019, and then do the patch, as follows:

Debugging with GDB

gef➤ break *0x401019

Breakpoint 1 at 0x401019

gef➤ r

gef➤ patch string 0x402000 "Patched!\\x0a"

gef➤ c

Continuing.

Patched!

Academy!

We see that we successfully modified the string and got Patched!\n Academy! instead of the old string. Notice how we used \x0a for adding a new line after our string.

Registers

We also note that we did not replace the entire string. This is because we only modified the characters up to the length of our string and left the remainder of the old string. Finally, the write system call specified a length of 0x12 of bytes to be printed.

To fix this, let's modify the value stored in $rdx to the length of our string, which is 0x9. We will only patch a size of one byte. We will go into details of how syscall works later in the module. Let us demonstrate using set to modify $rdx, as follows:

Debugging with GDB

gef➤ break *0x401019

Breakpoint 1 at 0x401019

gef➤ r

gef➤ patch string 0x402000 "Patched!\\x0a"

gef➤ set $rdx=0x9

gef➤ c

Continuing.

Patched!

We see that we successfully modified the final printed string and have the program output something of our choosing. The ability to modify values of registers and addresses will help us a lot through debugging and binary exploitation, as it allows us to test various values and conditions without having to change the code and recompile the binary every time.

The ability to set breakpoints to stop the execution, step through a program and each of its instructions, examine various data and addresses at each point, and modify values when needed, enables us to do proper debugging and reverse engineering.

Whether we want to see exactly why our program is failing or understand how a program is running and what it's doing at each point, GDB becomes very handy.

For penetration testing, this process enables us to understand how a program handles input at a certain point and exactly why it's failing. This allows us to develop exploits that take advantage of such failures, as we will learn in the Binary Exploitation modules.

So far, we have learned the basics of computer and CPU architecture and the basics of Assembly language and debugging. We will now start learning various x86 assembly instructions. We are likely to run into these types of instructions during penetration testing and reverse engineering exercises, so understanding how they work gives us the ability to interpret what they are doing and understand what the program is doing.

We will start by learning how to move data and values between registers and memory addresses. Then, we will learn instructions that take one operand (Unary Operations) and instructions with two operands ( Binary Instructions). Later on, we will go through assembly control instructions and shellcoding.

Before we start, however, let's discuss the program we will be developing throughout this module, using the various instructions we will learn.\

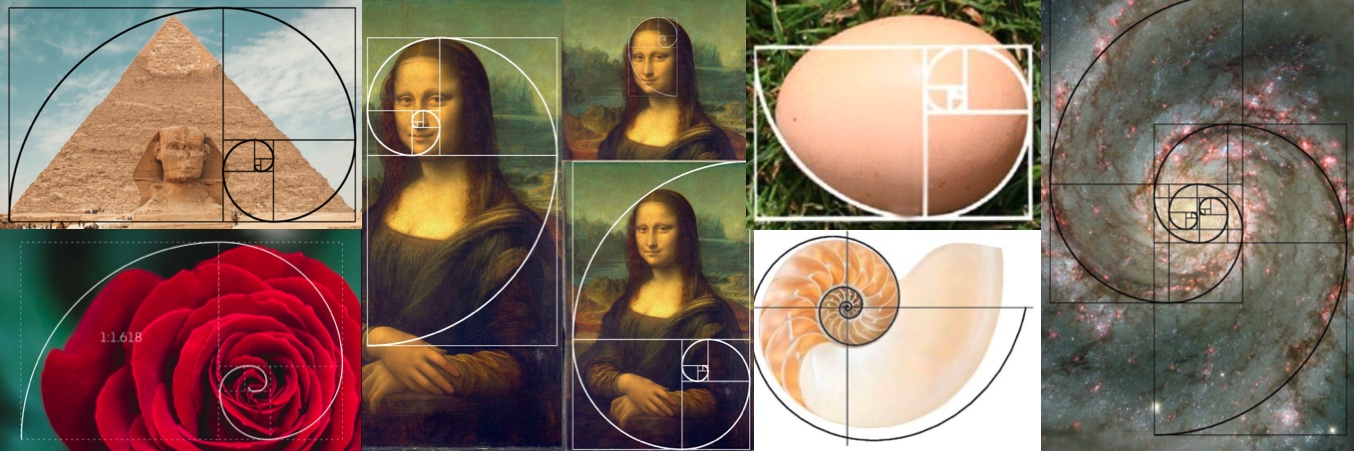

We will be developing a basic Fibonacci sequence calculator using x86 assembly language.

At the simplest term, a Fibonacci number is the sum of the two numbers preceding it in the sequence (i.e. Fn``= Fn-1``+ Fn-2). For example, if we start with F0=0 and F1=1, then F2 is F1``+ F0, which is F2``= 1 + 0 -> 1.\

Following the same formula, F3 is F3=1+1=2, F4 is F4``= 2 + 1 -> 3, and so on.

If we continue until F10, this is the sequence we would have: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55. As we can see, each number equals the sum of the two before it.