The cheat sheet is a useful command reference for this module.

Web reconnaissance is the first step in any security assessment or penetration testing engagement. It's akin to a detective's initial investigation, meticulously gathering clues and evidence about a target before formulating a plan of action. In the digital realm, this translates to accumulating information about a website or web application to identify potential vulnerabilities, security misconfigurations, and valuable assets.

The primary goals of web reconnaissance revolve around gaining a comprehensive understanding of the target's digital footprint. This includes:

Identifying Assets: Discovering all associated domains, subdomains, and IP addresses provides a map of the target's online presence.Uncovering Hidden Information: Web reconnaissance aims to uncover directories, files, and technologies that are not readily apparent and could serve as entry points for an attacker.Analyzing the Attack Surface: By identifying open ports, running services, and software versions, you can assess the potential vulnerabilities and weaknesses of the target.Gathering Intelligence: Collecting information about employees, email addresses, and technologies used can aid in social engineering attacks or identifying specific vulnerabilities associated with certain software.Web reconnaissance can be conducted using either active or passive techniques, each with its own advantages and drawbacks:

| Type | Description | Risk of Detection | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Reconnaissance | Involves directly interacting with the target system, such as sending probes or requests. | Higher | Port scanning, vulnerability scanning, network mapping |

| Passive Reconnaissance | Gathers information without directly interacting with the target, relying on publicly available data. | Lower | Search engine queries, WHOIS lookups, DNS enumeration, web archive analysis, social media |

WHOIS is a query and response protocol used to retrieve information about domain names, IP addresses, and other internet resources. It's essentially a directory service that details who owns a domain, when it was registered, contact information, and more. In the context of web reconnaissance, WHOIS lookups can be a valuable source of information, potentially revealing the identity of the website owner, their contact information, and other details that could be used for further investigation or social engineering attacks.

For example, if you wanted to find out who owns the domain example.com, you could run the following command in your terminal:

Code: bash

whois example.com

This would return a wealth of information, including the registrar, registration, and expiration dates, nameservers, and contact information for the domain owner.

However, it's important to note that WHOIS data can be inaccurate or intentionally obscured, so it's always wise to verify the information from multiple sources. Privacy services can also mask the true owner of a domain, making it more difficult to obtain accurate information through WHOIS.

The Domain Name System (DNS) functions as the internet's GPS, translating user-friendly domain names into the numerical IP addresses computers use to communicate. Like GPS converting a destination's name into coordinates, DNS ensures your browser reaches the correct website by matching its name with its IP address. This eliminates memorizing complex numerical addresses, making web navigation seamless and efficient.

The dig command allows you to query DNS servers directly, retrieving specific information about domain names. For instance, if you want to find the IP address associated with example.com, you can execute the following command:

Code: bash

dig example.com A

This command instructs dig to query the DNS for the A record (which maps a hostname to an IPv4 address) of example.com. The output will typically include the requested IP address, along with additional details about the query and response. By mastering the dig command and understanding the various DNS record types, you gain the ability to extract valuable information about a target's infrastructure and online presence.

DNS servers store various types of records, each serving a specific purpose:

| Record Type | Description |

|---|---|

| A | Maps a hostname to an IPv4 address. |

| AAAA | Maps a hostname to an IPv6 address. |

| CNAME | Creates an alias for a hostname, pointing it to another hostname. |

| MX | Specifies mail servers responsible for handling email for the domain. |

| NS | Delegates a DNS zone to a specific authoritative name server. |

| TXT | Stores arbitrary text information. |

| SOA | Contains administrative information about a DNS zone. |

Subdomains are essentially extensions of a primary domain name, often used to organize different sections or services within a website. For example, a company might use mail.example.com for their email server or blog.example.com for their blog.

From a reconnaissance perspective, subdomains are incredibly valuable. They can expose additional attack surfaces, reveal hidden services, and provide clues about the internal structure of a target's network. Subdomains might host development servers, staging environments, or even forgotten applications that haven't been properly secured.

The process of discovering subdomains is known as subdomain enumeration. There are two main approaches to subdomain enumeration:

| Approach | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

Active Enumeration |

Directly interacts with the target's DNS servers or utilizes tools to probe for subdomains. | Brute-forcing, DNS zone transfers |

Passive Enumeration |

Collects information about subdomains without directly interacting with the target, relying on public sources. | Certificate Transparency (CT) logs, search engine queries |

Active enumeration can be more thorough but carries a higher risk of detection. Conversely, passive enumeration is stealthier but may not uncover all subdomains. Combining both techniques can significantly increase the likelihood of discovering a comprehensive list of subdomains associated with your target, expanding your understanding of their online presence and potential vulnerabilities.

Subdomain brute-forcing is a proactive technique used in web reconnaissance to uncover subdomains that may not be readily apparent through passive methods. It involves systematically generating many potential subdomain names and testing them against the target's DNS server to see if they exist. This approach can unveil hidden subdomains that may host valuable information, development servers, or vulnerable applications.

One of the most versatile tools for subdomain brute-forcing is dnsenum. This powerful command-line tool combines various DNS enumeration techniques, including dictionary-based brute-forcing, to uncover subdomains associated with your target.

To use dnsenum for subdomain brute-forcing, you'll typically provide it with the target domain and a wordlist containing potential subdomain names. The tool will then systematically query the DNS server for each potential subdomain and report any that exist.

For example, the following command would attempt to brute-force subdomains of example.com using a wordlist named subdomains.txt:

Code: bash

dnsenum example.com -f subdomains.txt

DNS zone transfers, also known as AXFR (Asynchronous Full Transfer) requests, offer a potential goldmine of information for web reconnaissance. A zone transfer is a mechanism for replicating DNS data across servers. When a zone transfer is successful, it provides a complete copy of the DNS zone file, which contains a wealth of details about the target domain.

This zone file lists all the domain's subdomains, their associated IP addresses, mail server configurations, and other DNS records. This is akin to obtaining a blueprint of the target's DNS infrastructure for a reconnaissance expert.

To attempt a zone transfer, you can use the dig command with the axfr (full zone transfer) option. For example, to request a zone transfer from the DNS server ns1.example.com for the domain example.com, you would execute:

Code: bash

dig @ns1.example.com example.com axfr

However, zone transfers are not always permitted. Many DNS servers are configured to restrict zone transfers to authorized secondary servers only. Misconfigured servers, though, may allow zone transfers from any source, inadvertently exposing sensitive information.

Virtual hosting is a technique that allows multiple websites to share a single IP address. Each website is associated with a unique hostname, which is used to direct incoming requests to the correct site. This can be a cost-effective way for organizations to host multiple websites on a single server, but it can also create a challenge for web reconnaissance.

Since multiple websites share the same IP address, simply scanning the IP won't reveal all the hosted sites. You need a tool that can test different hostnames against the IP address to see which ones respond.

Gobuster is a versatile tool that can be used for various types of brute-forcing, including virtual host discovery. Its vhost mode is designed to enumerate virtual hosts by sending requests to the target IP address with different hostnames. If a virtual host is configured for a specific hostname, Gobuster will receive a response from the web server.

To use Gobuster to brute-force virtual hosts, you'll need a wordlist containing potential hostnames. Here's an example command:

Code: bash

gobuster vhost -u http://192.0.2.1 -w hostnames.txt

In this example, -u specifies the target IP address, and -w specifies the wordlist file. Gobuster will then systematically try each hostname in the wordlist and report any that results in a valid response from the web server.

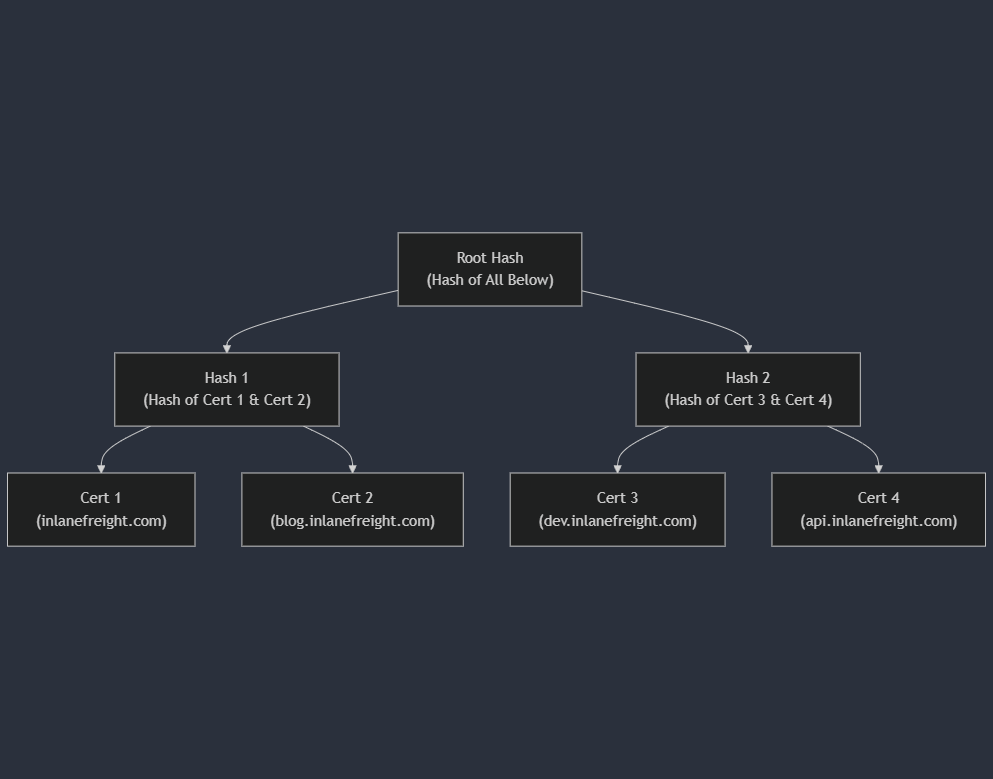

Certificate Transparency (CT) logs offer a treasure trove of subdomain information for passive reconnaissance. These publicly accessible logs record SSL/TLS certificates issued for domains and their subdomains, serving as a security measure to prevent fraudulent certificates. For reconnaissance, they offer a window into potentially overlooked subdomains.

The crt.sh website provides a searchable interface for CT logs. To efficiently extract subdomains using crt.sh within your terminal, you can use a command like this:

Code: bash

curl -s "https://crt.sh/?q=%25.example.com&output=json" | jq -r '.[].name_value' | sed 's/\*\.//g' | sort -u

This command fetches JSON-formatted data from crt.sh for example.com (the % is a wildcard), extracts domain names using jq, removes any wildcard prefixes (*.) with sed, and finally sorts and deduplicates the results.

Web crawling is the automated exploration of a website's structure. A web crawler, or spider, systematically navigates through web pages by following links, mimicking a user's browsing behavior. This process maps out the site's architecture and gathers valuable information embedded within the pages.

A crucial file that guides web crawlers is robots.txt. This file resides in a website's root directory and dictates which areas are off-limits for crawlers. Analyzing robots.txt can reveal hidden directories or sensitive areas that the website owner doesn't want to be indexed by search engines.

Scrapy is a powerful and efficient Python framework for large-scale web crawling and scraping projects. It provides a structured approach to defining crawling rules, extracting data, and handling various output formats.

Here's a basic Scrapy spider example to extract links from example.com:

Code: python

import scrapy

class ExampleSpider(scrapy.Spider):

name = "example"

start_urls = ['http://example.com/']

def parse(self, response):

for link in response.css('a::attr(href)').getall():

if any(link.endswith(ext) for ext in self.interesting_extensions):

yield {"file": link}

elif not link.startswith("#") and not link.startswith("mailto:"):

yield response.follow(link, callback=self.parse)

After running the Scrapy spider, you'll have a file containing scraped data (e.g., example_data.json). You can analyze these results using standard command-line tools. For instance, to extract all links:

Code: bash

jq -r '.[] | select(.file != null) | .file' example_data.json | sort -u

This command uses jq to extract links, awk to isolate file extensions, sort to order them, and uniq -c to count their occurrences. By scrutinizing the extracted data, you can identify patterns, anomalies, or sensitive files that might be of interest for further investigation.

Leveraging search engines for reconnaissance involves utilizing their vast indexes of web content to uncover information about your target. This passive technique, often referred to as Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) gathering, can yield valuable insights without directly interacting with the target's systems.

By employing advanced search operators and specialized queries known as "Google Dorks," you can pinpoint specific information buried within search results. Here's a table of some useful search operators for web reconnaissance:

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

site: |

Restricts search results to a specific website. | site:example.com "password reset" |

inurl: |

Searches for a specific term in the URL of a page. | inurl:admin login |

filetype: |

Limits results to files of a specific type. | filetype:pdf "confidential report" |

intitle: |

Searches for a term within the title of a page. | intitle:"index of" /backup |

cache: |

Shows the cached version of a webpage. | cache:example.com |

"search term" |

Searches for the exact phrase within quotation marks. | "internal error" site:example.com |

OR |

Combines multiple search terms. | inurl:admin OR inurl:login |

- |

Excludes specific terms from search results. | inurl:admin -intext:wordpress |

By creatively combining these operators and crafting targeted queries, you can uncover sensitive documents, exposed directories, login pages, and other valuable information that may aid in your reconnaissance efforts.

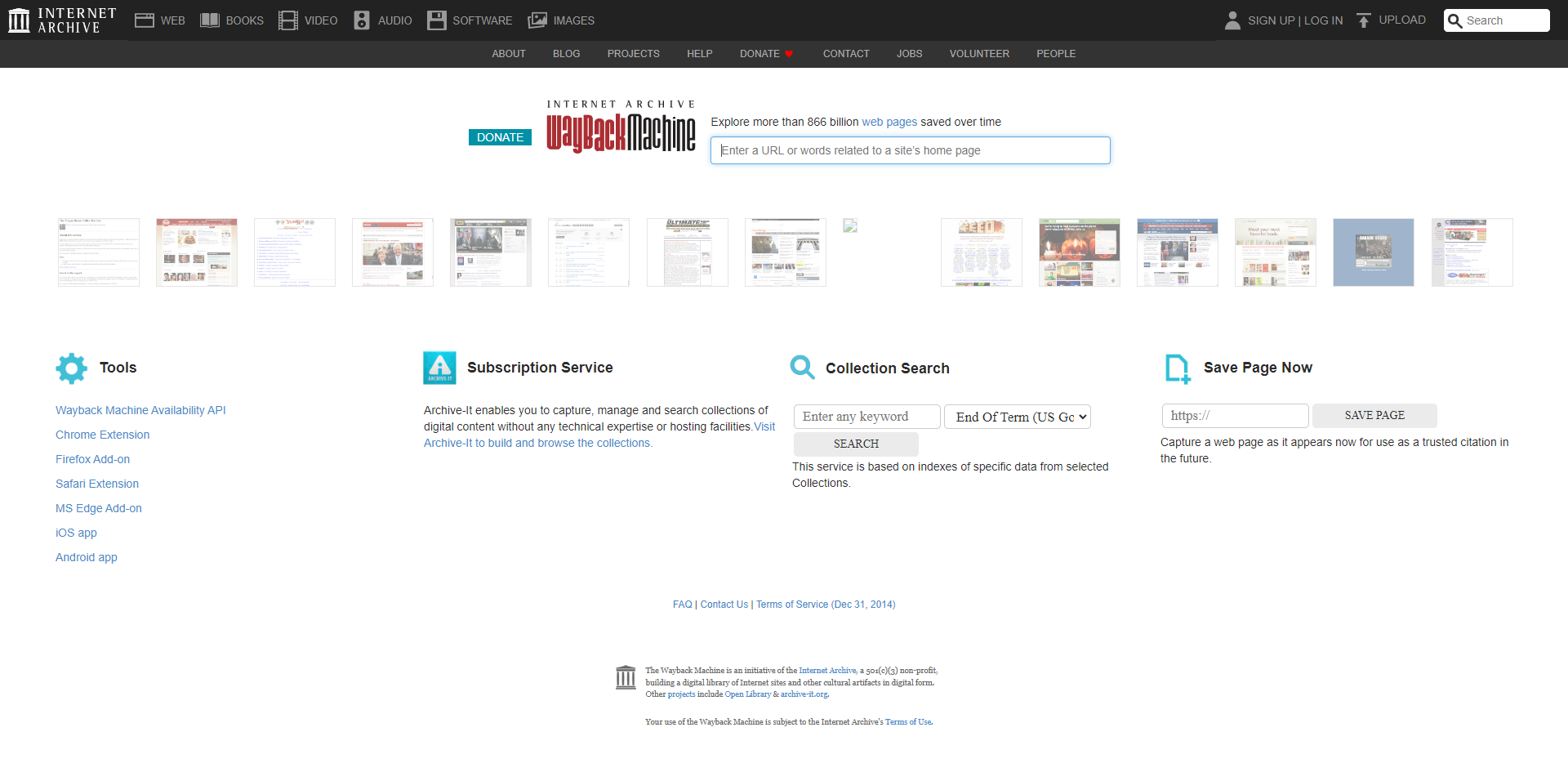

Web archives are digital repositories that store snapshots of websites across time, providing a historical record of their evolution. Among these archives, the Wayback Machine is the most comprehensive and accessible resource for web reconnaissance.

The Wayback Machine, a project by the Internet Archive, has been archiving the web for over two decades, capturing billions of web pages from across the globe. This massive historical data collection can be an invaluable resource for security researchers and investigators.

| Feature | Description | Use Case in Reconnaissance |

|---|---|---|

Historical Snapshots |

View past versions of websites, including pages, content, and design changes. | Identify past website content or functionality that is no longer available. |

Hidden Directories |

Explore directories and files that may have been removed or hidden from the current version of the website. | Discover sensitive information or backups that were inadvertently left accessible in previous versions. |

Content Changes |

Track changes in website content, including text, images, and links. | Identify patterns in content updates and assess the evolution of a website's security posture. |

By leveraging the Wayback Machine, you can gain a historical perspective on your target's online presence, potentially revealing vulnerabilities that may have been overlooked in the current version of the website.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

export TARGET="domain.tld" |

Assign target to an environment variable. |

whois $TARGET |

WHOIS lookup for the target. |

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

nslookup $TARGET |

Identify the A record for the target domain. |

nslookup -query=A $TARGET |

Identify the A record for the target domain. |

dig $TARGET @<nameserver/IP> |

Identify the A record for the target domain. |

dig a $TARGET @<nameserver/IP> |

Identify the A record for the target domain. |

nslookup -query=PTR <IP> |

Identify the PTR record for the target IP address. |

dig -x <IP> @<nameserver/IP> |

Identify the PTR record for the target IP address. |

nslookup -query=ANY $TARGET |

Identify ANY records for the target domain. |

dig any $TARGET @<nameserver/IP> |

Identify ANY records for the target domain. |

nslookup -query=TXT $TARGET |

Identify the TXT records for the target domain. |

dig txt $TARGET @<nameserver/IP> |

Identify the TXT records for the target domain. |

nslookup -query=MX $TARGET |

Identify the MX records for the target domain. |

dig mx $TARGET @<nameserver/IP> |

Identify the MX records for the target domain. |

| Resource/Command | Description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

VirusTotal |

https://www.virustotal.com/gui/home/url | |||

Censys |

https://censys.io/ | |||

Crt.sh |

https://crt.sh/ | |||

| `curl -s https://sonar.omnisint.io/subdomains/{domain} \ | jq -r '.[]' \ | sort -u` | All subdomains for a given domain. | |

| `curl -s https://sonar.omnisint.io/tlds/{domain} \ | jq -r '.[]' \ | sort -u` | All TLDs found for a given domain. | |

| `curl -s https://sonar.omnisint.io/all/{domain} \ | jq -r '.[]' \ | sort -u` | All results across all TLDs for a given domain. | |

| `curl -s https://sonar.omnisint.io/reverse/{ip} \ | jq -r '.[]' \ | sort -u` | Reverse DNS lookup on IP address. | |

| `curl -s https://sonar.omnisint.io/reverse/{ip}/{mask} \ | jq -r '.[]' \ | sort -u` | Reverse DNS lookup of a CIDR range. | |

| `curl -s "https://crt.sh/?q=${TARGET}&output=json" \ | jq -r '.[] \ | "(.name_value)\n(.common_name)"' \ | sort -u` | Certificate Transparency. |

| `cat sources.txt \ | while read source; do theHarvester -d "${TARGET}" -b $source -f "${source}-${TARGET}";done` | Searching for subdomains and other information on the sources provided in the source.txt list. |

Sources.txt

baidu

bufferoverun

crtsh

hackertarget

otx

projecdiscovery

rapiddns

sublist3r

threatcrowd

trello

urlscan

vhost

virustotal

zoomeye

| Resource/Command | Description |

|---|---|

Netcraft |

https://www.netcraft.com/ |

WayBackMachine |

http://web.archive.org/ |

WayBackURLs |

https://github.com/tomnomnom/waybackurls |

waybackurls -dates https://$TARGET > waybackurls.txt |

Crawling URLs from a domain with the date it was obtained. |

| Resource/Command | Description | |

|---|---|---|

curl -I "http://${TARGET}" |

Display HTTP headers of the target webserver. | |

whatweb -a https://www.facebook.com -v |

Technology identification. | |

Wappalyzer |

https://www.wappalyzer.com/ | |

wafw00f -v https://$TARGET |

WAF Fingerprinting. | |

Aquatone |

https://github.com/michenriksen/aquatone | |

| `cat subdomain.list \ | aquatone -out ./aquatone -screenshot-timeout 1000` | Makes screenshots of all subdomains in the subdomain.list. |

| Resource/Command | Description |

|---|---|

HackerTarget |

https://hackertarget.com/zone-transfer/ |

SecLists |

https://github.com/danielmiessler/SecLists |

nslookup -type=any -query=AXFR $TARGET nameserver.target.domain |

Zone Transfer using Nslookup against the target domain and its nameserver. |

gobuster dns -q -r "${NS}" -d "${TARGET}" -w "${WORDLIST}" -p ./patterns.txt -o "gobuster_${TARGET}.txt" |

Bruteforcing subdomains. |

| Resource/Command | Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|

curl -s http://192.168.10.10 -H "Host: randomtarget.com" |

Changing the HOST HTTP header to request a specific domain. | ||

| `cat ./vhosts.list \ | while read vhost;do echo "\n**\nFUZZING: ${vhost}\n**";curl -s -I http:// |

grep "Content-Length: ";done` | Bruteforcing for possible virtual hosts on the target domain. |

ffuf -w ./vhosts -u http://<IP address> -H "HOST: FUZZ.target.domain" -fs 612 |

Bruteforcing for possible virtual hosts on the target domain using ffuf. |

| Resource/Command | Description |

|---|---|

ZAP |

https://www.zaproxy.org/ |

ffuf -recursion -recursion-depth 1 -u http://192.168.10.10/FUZZ -w /opt/useful/SecLists/Discovery/Web-Content/raft-small-directories-lowercase.txt |

Discovering files and folders that cannot be spotted by browsing the website. |

ffuf -w ./folders.txt:FOLDERS,./wordlist.txt:WORDLIST,./extensions.txt:EXTENSIONS -u http://www.target.domain/FOLDERS/WORDLISTEXTENSIONS |

Mutated bruteforcing against the target web server. |

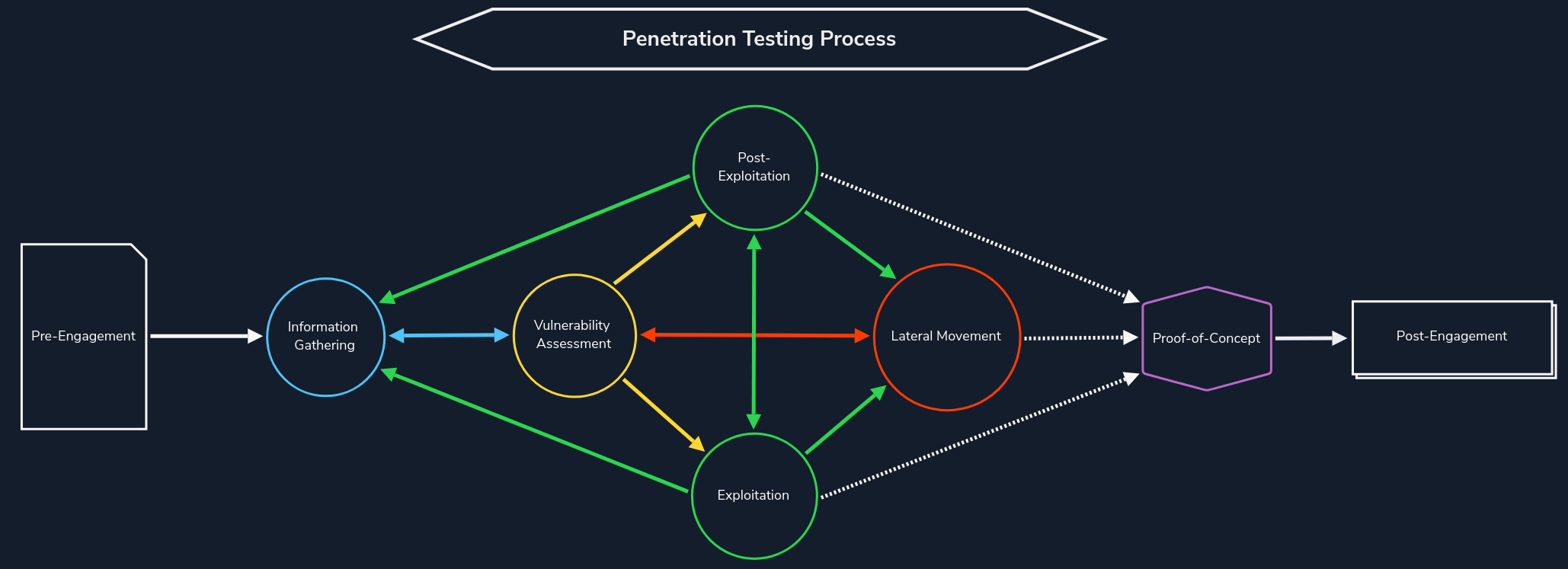

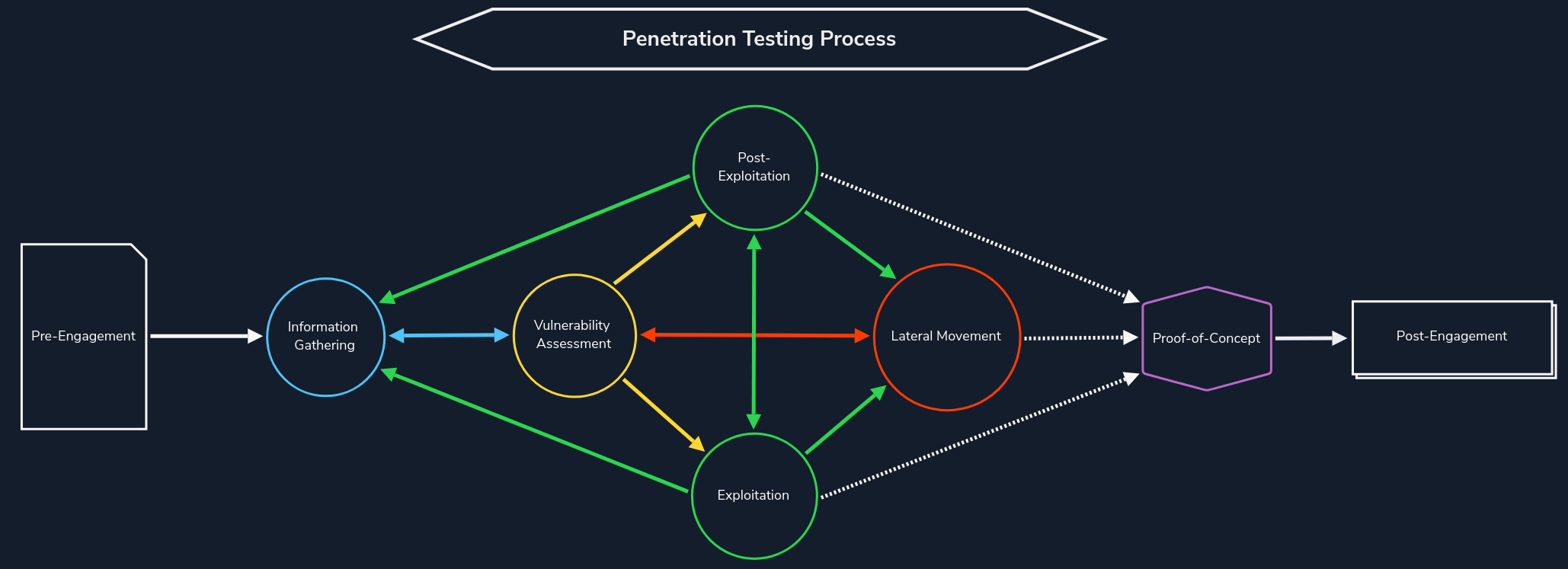

Web Reconnaissance is the foundation of a thorough security assessment. This process involves systematically and meticulously collecting information about a target website or web application. Think of it as the preparatory phase before delving into deeper analysis and potential exploitation. It forms a critical part of the "Information Gathering" phase of the Penetration Testing Process.

The primary goals of web reconnaissance include:

Identifying Assets: Uncovering all publicly accessible components of the target, such as web pages, subdomains, IP addresses, and technologies used. This step provides a comprehensive overview of the target's online presence.Discovering Hidden Information: Locating sensitive information that might be inadvertently exposed, including backup files, configuration files, or internal documentation. These findings can reveal valuable insights and potential entry points for attacks.Analysing the Attack Surface: Examining the target's attack surface to identify potential vulnerabilities and weaknesses. This involves assessing the technologies used, configurations, and possible entry points for exploitation.Gathering Intelligence: Collecting information that can be leveraged for further exploitation or social engineering attacks. This includes identifying key personnel, email addresses, or patterns of behaviour that could be exploited.Attackers leverage this information to tailor their attacks, allowing them to target specific weaknesses and bypass security measures. Conversely, defenders use recon to proactively identify and patch vulnerabilities before malicious actors can leverage them.

Web reconnaissance encompasses two fundamental methodologies: active and passive reconnaissance. Each approach offers distinct advantages and challenges, and understanding their differences is crucial for adequate information gathering.

In active reconnaissance, the attacker directly interacts with the target system to gather information. This interaction can take various forms:

| Technique | Description | Example | Tools | Risk of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Port Scanning |

Identifying open ports and services running on the target. | Using Nmap to scan a web server for open ports like 80 (HTTP) and 443 (HTTPS). | Nmap, Masscan, Unicornscan | High: Direct interaction with the target can trigger intrusion detection systems (IDS) and firewalls. |

Vulnerability Scanning |

Probing the target for known vulnerabilities, such as outdated software or misconfigurations. | Running Nessus against a web application to check for SQL injection flaws or cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerabilities. | Nessus, OpenVAS, Nikto | High: Vulnerability scanners send exploit payloads that security solutions can detect. |

Network Mapping |

Mapping the target's network topology, including connected devices and their relationships. | Using traceroute to determine the path packets take to reach the target server, revealing potential network hops and infrastructure. | Traceroute, Nmap | Medium to High: Excessive or unusual network traffic can raise suspicion. |

Banner Grabbing |

Retrieving information from banners displayed by services running on the target. | Connecting to a web server on port 80 and examining the HTTP banner to identify the web server software and version. | Netcat, curl | Low: Banner grabbing typically involves minimal interaction but can still be logged. |

OS Fingerprinting |

Identifying the operating system running on the target. | Using Nmap's OS detection capabilities (-O) to determine if the target is running Windows, Linux, or another OS. |

Nmap, Xprobe2 | Low: OS fingerprinting is usually passive, but some advanced techniques can be detected. |

Service Enumeration |

Determining the specific versions of services running on open ports. | Using Nmap's service version detection (-sV) to determine if a web server is running Apache 2.4.50 or Nginx 1.18.0. |

Nmap | Low: Similar to banner grabbing, service enumeration can be logged but is less likely to trigger alerts. |

Web Spidering |

Crawling the target website to identify web pages, directories, and files. | Running a web crawler like Burp Suite Spider or OWASP ZAP Spider to map out the structure of a website and discover hidden resources. | Burp Suite Spider, OWASP ZAP Spider, Scrapy (customisable) | Low to Medium: Can be detected if the crawler's behaviour is not carefully configured to mimic legitimate traffic. |

Active reconnaissance provides a direct and often more comprehensive view of the target's infrastructure and security posture. However, it also carries a higher risk of detection, as the interactions with the target can trigger alerts or raise suspicion.

In contrast, passive reconnaissance involves gathering information about the target without directly interacting with it. This relies on analysing publicly available information and resources, such as:

| Technique | Description | Example | Tools | Risk of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Search Engine Queries |

Utilising search engines to uncover information about the target, including websites, social media profiles, and news articles. | Searching Google for "[Target Name] employees" to find employee information or social media profiles. |

Google, DuckDuckGo, Bing, and specialised search engines (e.g., Shodan) | Very Low: Search engine queries are normal internet activity and unlikely to trigger alerts. |

WHOIS Lookups |

Querying WHOIS databases to retrieve domain registration details. | Performing a WHOIS lookup on a target domain to find the registrant's name, contact information, and name servers. | whois command-line tool, online WHOIS lookup services | Very Low: WHOIS queries are legitimate and do not raise suspicion. |

DNS |

Analysing DNS records to identify subdomains, mail servers, and other infrastructure. | Using dig to enumerate subdomains of a target domain. |

dig, nslookup, host, dnsenum, fierce, dnsrecon | Very Low: DNS queries are essential for internet browsing and are not typically flagged as suspicious. |

Web Archive Analysis |

Examining historical snapshots of the target's website to identify changes, vulnerabilities, or hidden information. | Using the Wayback Machine to view past versions of a target website to see how it has changed over time. | Wayback Machine | Very Low: Accessing archived versions of websites is a normal activity. |

Social Media Analysis |

Gathering information from social media platforms like LinkedIn, Twitter, or Facebook. | Searching LinkedIn for employees of a target organisation to learn about their roles, responsibilities, and potential social engineering targets. | LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, specialised OSINT tools | Very Low: Accessing public social media profiles is not considered intrusive. |

Code Repositories |

Analysing publicly accessible code repositories like GitHub for exposed credentials or vulnerabilities. | Searching GitHub for code snippets or repositories related to the target that might contain sensitive information or code vulnerabilities. | GitHub, GitLab | Very Low: Code repositories are meant for public access, and searching them is not suspicious. |

Passive reconnaissance is generally considered stealthier and less likely to trigger alarms than active reconnaissance. However, it may yield less comprehensive information, as it relies on what's already publicly accessible.

In this module, we will delve into the essential tools and techniques used in web reconnaissance, starting with WHOIS. Understanding the WHOIS protocol provides a gateway to accessing vital information about domain registrations, ownership details, and the digital infrastructure of targets. This foundational knowledge sets the stage for more advanced recon methods we'll explore later.

WHOIS is a widely used query and response protocol designed to access databases that store information about registered internet resources. Primarily associated with domain names, WHOIS can also provide details about IP address blocks and autonomous systems. Think of it as a giant phonebook for the internet, letting you look up who owns or is responsible for various online assets.

WHOIS

root@htb[/htb]$ whois inlanefreight.com

[...]

Domain Name: inlanefreight.com

Registry Domain ID: 2420436757_DOMAIN_COM-VRSN

Registrar WHOIS Server: whois.registrar.amazon

Registrar URL: https://registrar.amazon.com

Updated Date: 2023-07-03T01:11:15Z

Creation Date: 2019-08-05T22:43:09Z

[...]

Each WHOIS record typically contains the following information:

Domain Name: The domain name itself (e.g., example.com)Registrar: The company where the domain was registered (e.g., GoDaddy, Namecheap)Registrant Contact: The person or organization that registered the domain.Administrative Contact: The person responsible for managing the domain.Technical Contact: The person handling technical issues related to the domain.Creation and Expiration Dates: When the domain was registered and when it's set to expire.Name Servers: Servers that translate the domain name into an IP address.The history of WHOIS is intrinsically linked to the vision and dedication of Elizabeth Feinler, a computer scientist who played a pivotal role in shaping the early internet.

In the 1970s, Feinler and her team at the Stanford Research Institute's Network Information Center (NIC) recognised the need for a system to track and manage the growing number of network resources on the ARPANET, the precursor to the modern internet. Their solution was the creation of the WHOIS directory, a rudimentary yet groundbreaking database that stored information about network users, hostnames, and domain names.

\

WHOIS data serves as a treasure trove of information for penetration testers during the reconnaissance phase of an assessment. It offers valuable insights into the target organisation's digital footprint and potential vulnerabilities:

Identifying Key Personnel: WHOIS records often reveal the names, email addresses, and phone numbers of individuals responsible for managing the domain. This information can be leveraged for social engineering attacks or to identify potential targets for phishing campaigns.Discovering Network Infrastructure: Technical details like name servers and IP addresses provide clues about the target's network infrastructure. This can help penetration testers identify potential entry points or misconfigurations.Historical Data Analysis: Accessing historical WHOIS records through services like WhoisFreaks can reveal changes in ownership, contact information, or technical details over time. This can be useful for tracking the evolution of the target's digital presence.Let's consider three scenarios to help illustrate the value of WHOIS data.

An email security gateway flags a suspicious email sent to multiple employees within a company. The email claims to be from the company's bank and urges recipients to click on a link to update their account information. A security analyst investigates the email and begins by performing a WHOIS lookup on the domain linked in the email.

The WHOIS record reveals the following:

Registration Date: The domain was registered just a few days ago.Registrant: The registrant's information is hidden behind a privacy service.Name Servers: The name servers are associated with a known bulletproof hosting provider often used for malicious activities.This combination of factors raises significant red flags for the analyst. The recent registration date, hidden registrant information, and suspicious hosting strongly suggest a phishing campaign. The analyst promptly alerts the company's IT department to block the domain and warns employees about the scam.

Further investigation into the hosting provider and associated IP addresses may uncover additional phishing domains or infrastructure the threat actor uses.

A security researcher is analysing a new strain of malware that has infected several systems within a network. The malware communicates with a remote server to receive commands and exfiltrate stolen data. To gain insights into the threat actor's infrastructure, the researcher performs a WHOIS lookup on the domain associated with the command-and-control (C2) server.

The WHOIS record reveals:

Registrant: The domain is registered to an individual using a free email service known for anonymity.Location: The registrant's address is in a country with a high prevalence of cybercrime.Registrar: The domain was registered through a registrar with a history of lax abuse policies.Based on this information, the researcher concludes that the C2 server is likely hosted on a compromised or "bulletproof" server. The researcher then uses the WHOIS data to identify the hosting provider and notify them of the malicious activity.

A cybersecurity firm tracks the activities of a sophisticated threat actor group known for targeting financial institutions. Analysts gather WHOIS data on multiple domains associated with the group's past campaigns to compile a comprehensive threat intelligence report.

By analysing the WHOIS records, analysts uncover the following patterns:

Registration Dates: The domains were registered in clusters, often shortly before major attacks.Registrants: The registrants use various aliases and fake identities.Name Servers: The domains often share the same name servers, suggesting a common infrastructure.Takedown History: Many domains have been taken down after attacks, indicating previous law enforcement or security interventions.These insights allow analysts to create a detailed profile of the threat actor's tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). The report includes indicators of compromise (IOCs) based on the WHOIS data, which other organisations can use to detect and block future attacks.

Before using the whois command, you'll need to ensure it's installed on your Linux system. It's a utility available through linux package managers, and if it's not installed, it can be installed simply with

Utilising WHOIS

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo apt update

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo apt install whois -y

The simplest way to access WHOIS data is through the whois command-line tool. Let's perform a WHOIS lookup on facebook.com:

Utilising WHOIS

root@htb[/htb]$ whois facebook.com

Domain Name: FACEBOOK.COM

Registry Domain ID: 2320948_DOMAIN_COM-VRSN

Registrar WHOIS Server: whois.registrarsafe.com

Registrar URL: http://www.registrarsafe.com

Updated Date: 2024-04-24T19:06:12Z

Creation Date: 1997-03-29T05:00:00Z

Registry Expiry Date: 2033-03-30T04:00:00Z

Registrar: RegistrarSafe, LLC

Registrar IANA ID: 3237

Registrar Abuse Contact Email: abusecomplaints@registrarsafe.com

Registrar Abuse Contact Phone: +1-650-308-7004

Domain Status: clientDeleteProhibited https://icann.org/epp#clientDeleteProhibited

Domain Status: clientTransferProhibited https://icann.org/epp#clientTransferProhibited

Domain Status: clientUpdateProhibited https://icann.org/epp#clientUpdateProhibited

Domain Status: serverDeleteProhibited https://icann.org/epp#serverDeleteProhibited

Domain Status: serverTransferProhibited https://icann.org/epp#serverTransferProhibited

Domain Status: serverUpdateProhibited https://icann.org/epp#serverUpdateProhibited

Name Server: A.NS.FACEBOOK.COM

Name Server: B.NS.FACEBOOK.COM

Name Server: C.NS.FACEBOOK.COM

Name Server: D.NS.FACEBOOK.COM

DNSSEC: unsigned

URL of the ICANN Whois Inaccuracy Complaint Form: https://www.icann.org/wicf/

>>> Last update of whois database: 2024-06-01T11:24:10Z <<<

[...]

Registry Registrant ID:

Registrant Name: Domain Admin

Registrant Organization: Meta Platforms, Inc.

[...]

The WHOIS output for facebook.com reveals several key details:

Domain Registration:

Registrar: RegistrarSafe, LLCCreation Date: 1997-03-29Expiry Date: 2033-03-30These details indicate that the domain is registered with RegistrarSafe, LLC, and has been active for a considerable period, suggesting its legitimacy and established online presence. The distant expiry date further reinforces its longevity.

Domain Owner:

Registrant/Admin/Tech Organization: Meta Platforms, Inc.Registrant/Admin/Tech Contact: Domain AdminThis information identifies Meta Platforms, Inc. as the organization behind facebook.com, and "Domain Admin" as the point of contact for domain-related matters. This is consistent with the expectation that Facebook, a prominent social media platform, is owned by Meta Platforms, Inc.

Domain Status:

clientDeleteProhibited, clientTransferProhibited, clientUpdateProhibited, serverDeleteProhibited, serverTransferProhibited, and serverUpdateProhibitedThese statuses indicate that the domain is protected against unauthorized changes, transfers, or deletions on both the client and server sides. This highlights a strong emphasis on security and control over the domain.

Name Servers:

A.NS.FACEBOOK.COM, B.NS.FACEBOOK.COM, C.NS.FACEBOOK.COM, D.NS.FACEBOOK.COMThese name servers are all within the facebook.com domain, suggesting that Meta Platforms, Inc. manages its DNS infrastructure. It is common practice for large organizations to maintain control and reliability over their DNS resolution.

Overall, the WHOIS output for facebook.com aligns with expectations for a well-established and secure domain owned by a large organization like Meta Platforms, Inc.

While the WHOIS record provides contact information for domain-related issues, it might not be directly helpful in identifying individual employees or specific vulnerabilities. This highlights the need to combine WHOIS data with other reconnaissance techniques to understand the target's digital footprint comprehensively.

The Domain Name System (DNS) acts as the internet's GPS, guiding your online journey from memorable landmarks (domain names) to precise numerical coordinates (IP addresses). Much like how GPS translates a destination name into latitude and longitude for navigation, DNS translates human-readable domain names (like www.example.com) into the numerical IP addresses (like 192.0.2.1) that computers use to communicate.

Imagine navigating a city by memorizing the exact latitude and longitude of every location you want to visit. It would be incredibly cumbersome and inefficient. DNS eliminates this complexity by allowing us to use easy-to-remember domain names instead. When you type a domain name into your browser, DNS acts as your navigator, swiftly finding the corresponding IP address and directing your request to the correct destination on the internet.

Without DNS, navigating the online world would be akin to driving without a map or GPS – a frustrating and error-prone endeavour.

Imagine you want to visit a website like www.example.com. You type this friendly domain name into your browser, but your computer doesn't understand words – it speaks the language of numbers, specifically IP addresses. So, how does your computer find the website's IP address? Enter DNS, the internet's trusty translator.

Your Computer Asks for Directions (DNS Query): When you enter the domain name, your computer first checks its memory (cache) to see if it remembers the IP address from a previous visit. If not, it reaches out to a DNS resolver, usually provided by your internet service provider (ISP).The DNS Resolver Checks its Map (Recursive Lookup): The resolver also has a cache, and if it doesn't find the IP address there, it starts a journey through the DNS hierarchy. It begins by asking a root name server, which is like the librarian of the internet.Root Name Server Points the Way: The root server doesn't know the exact address but knows who does – the Top-Level Domain (TLD) name server responsible for the domain's ending (e.g., .com, .org). It points the resolver in the right direction.TLD Name Server Narrows It Down: The TLD name server is like a regional map. It knows which authoritative name server is responsible for the specific domain you're looking for (e.g., example.com) and sends the resolver there.Authoritative Name Server Delivers the Address: The authoritative name server is the final stop. It's like the street address of the website you want. It holds the correct IP address and sends it back to the resolver.The DNS Resolver Returns the Information: The resolver receives the IP address and gives it to your computer. It also remembers it for a while (caches it), in case you want to revisit the website soon.Your Computer Connects: Now that your computer knows the IP address, it can connect directly to the web server hosting the website, and you can start browsing.The hosts file is a simple text file used to map hostnames to IP addresses, providing a manual method of domain name resolution that bypasses the DNS process. While DNS automates the translation of domain names to IP addresses, the hosts file allows for direct, local overrides. This can be particularly useful for development, troubleshooting, or blocking websites.

The hosts file is located in C:\Windows\System32\drivers\etc\hosts on Windows and in /etc/hosts on Linux and MacOS. Each line in the file follows the format:

Code: txt

<IP Address> <Hostname> [<Alias> ...]

For example:

Code: txt

127.0.0.1 localhost

192.168.1.10 devserver.local

To edit the hosts file, open it with a text editor using administrative/root privileges. Add new entries as needed, and then save the file. The changes take effect immediately without requiring a system restart.

Common uses include redirecting a domain to a local server for development:

Code: txt

127.0.0.1 myapp.local

testing connectivity by specifying an IP address:

Code: txt

192.168.1.20 testserver.local

or blocking unwanted websites by redirecting their domains to a non-existent IP address:

Code: txt

0.0.0.0 unwanted-site.com

Think of the DNS process as a relay race. Your computer starts with the domain name and passes it along to the resolver. The resolver then passes the request to the root server, the TLD server, and finally, the authoritative server, each one getting closer to the destination. Once the IP address is found, it's relayed back down the chain to your computer, allowing you to access the website.

In the Domain Name System (DNS), a zone is a distinct part of the domain namespace that a specific entity or administrator manages. Think of it as a virtual container for a set of domain names. For example, example.com and all its subdomains (like mail.example.com or blog.example.com) would typically belong to the same DNS zone.

The zone file, a text file residing on a DNS server, defines the resource records (discussed below) within this zone, providing crucial information for translating domain names into IP addresses.

To illustrate, here's a simplified example of what a zone file, for example.com might look like:

Code: zone

$TTL 3600 ; Default Time-To-Live (1 hour)

@ IN SOA ns1.example.com. admin.example.com. (

2024060401 ; Serial number (YYYYMMDDNN)

3600 ; Refresh interval

900 ; Retry interval

604800 ; Expire time

86400 ) ; Minimum TTL

@ IN NS ns1.example.com.

@ IN NS ns2.example.com.

@ IN MX 10 mail.example.com.

www IN A 192.0.2.1

mail IN A 198.51.100.1

ftp IN CNAME www.example.com.

This file defines the authoritative name servers (NS records), mail server (MX record), and IP addresses (A records) for various hosts within the example.com domain.

DNS servers store various resource records, each serving a specific purpose in the domain name resolution process. Let's explore some of the most common DNS concepts:

| DNS Concept | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

Domain Name |

A human-readable label for a website or other internet resource. | www.example.com |

IP Address |

A unique numerical identifier assigned to each device connected to the internet. | 192.0.2.1 |

DNS Resolver |

A server that translates domain names into IP addresses. | Your ISP's DNS server or public resolvers like Google DNS (8.8.8.8) |

Root Name Server |

The top-level servers in the DNS hierarchy. | There are 13 root servers worldwide, named A-M: a.root-servers.net |

TLD Name Server |

Servers responsible for specific top-level domains (e.g., .com, .org). | Verisign for .com, PIR for .org |

Authoritative Name Server |

The server that holds the actual IP address for a domain. | Often managed by hosting providers or domain registrars. |

DNS Record Types |

Different types of information stored in DNS. | A, AAAA, CNAME, MX, NS, TXT, etc. |

Now that we've explored the fundamental concepts of DNS, let's dive deeper into the building blocks of DNS information – the various record types. These records store different types of data associated with domain names, each serving a specific purpose:

| Record Type | Full Name | Description | Zone File Example |

|---|---|---|---|

A |

Address Record | Maps a hostname to its IPv4 address. | www.example.com. IN A 192.0.2.1 |

AAAA |

IPv6 Address Record | Maps a hostname to its IPv6 address. | www.example.com. IN AAAA 2001:db8:85a3::8a2e:370:7334 |

CNAME |

Canonical Name Record | Creates an alias for a hostname, pointing it to another hostname. | blog.example.com. IN CNAME webserver.example.net. |

MX |

Mail Exchange Record | Specifies the mail server(s) responsible for handling email for the domain. | example.com. IN MX 10 mail.example.com. |

NS |

Name Server Record | Delegates a DNS zone to a specific authoritative name server. | example.com. IN NS ns1.example.com. |

TXT |

Text Record | Stores arbitrary text information, often used for domain verification or security policies. | example.com. IN TXT "v=spf1 mx -all" (SPF record) |

SOA |

Start of Authority Record | Specifies administrative information about a DNS zone, including the primary name server, responsible person's email, and other parameters. | example.com. IN SOA ns1.example.com. admin.example.com. 2024060301 10800 3600 604800 86400 |

SRV |

Service Record | Defines the hostname and port number for specific services. | _sip._udp.example.com. IN SRV 10 5 5060 sipserver.example.com. |

PTR |

Pointer Record | Used for reverse DNS lookups, mapping an IP address to a hostname. | 1.2.0.192.in-addr.arpa. IN PTR www.example.com. |

The "IN" in the examples stands for "Internet." It's a class field in DNS records that specifies the protocol family. In most cases, you'll see "IN" used, as it denotes the Internet protocol suite (IP) used for most domain names. Other class values exist (e.g., CH for Chaosnet, HS for Hesiod) but are rarely used in modern DNS configurations.

In essence, "IN" is simply a convention that indicates that the record applies to the standard internet protocols we use today. While it might seem like an extra detail, understanding its meaning provides a deeper understanding of DNS record structure.

DNS is not merely a technical protocol for translating domain names; it's a critical component of a target's infrastructure that can be leveraged to uncover vulnerabilities and gain access during a penetration test:

Uncovering Assets: DNS records can reveal a wealth of information, including subdomains, mail servers, and name server records. For instance, a CNAME record pointing to an outdated server (dev.example.com CNAME oldserver.example.net) could lead to a vulnerable system.Mapping the Network Infrastructure: You can create a comprehensive map of the target's network infrastructure by analysing DNS data. For example, identifying the name servers (NS records) for a domain can reveal the hosting provider used, while an A record for loadbalancer.example.com can pinpoint a load balancer. This helps you understand how different systems are connected, identify traffic flow, and pinpoint potential choke points or weaknesses that could be exploited during a penetration test.Monitoring for Changes: Continuously monitoring DNS records can reveal changes in the target's infrastructure over time. For example, the sudden appearance of a new subdomain (vpn.example.com) might indicate a new entry point into the network, while a TXT record containing a value like _1password=... strongly suggests the organization is using 1Password, which could be leveraged for social engineering attacks or targeted phishing campaigns.Having established a solid understanding of DNS fundamentals and its various record types, let's now transition to the practical. This section will explore the tools and techniques for leveraging DNS for web reconnaissance.

DNS reconnaissance involves utilizing specialized tools designed to query DNS servers and extract valuable information. Here are some of the most popular and versatile tools in the arsenal of web recon professionals:

| Tool | Key Features | Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

dig |

Versatile DNS lookup tool that supports various query types (A, MX, NS, TXT, etc.) and detailed output. | Manual DNS queries, zone transfers (if allowed), troubleshooting DNS issues, and in-depth analysis of DNS records. |

nslookup |

Simpler DNS lookup tool, primarily for A, AAAA, and MX records. | Basic DNS queries, quick checks of domain resolution and mail server records. |

host |

Streamlined DNS lookup tool with concise output. | Quick checks of A, AAAA, and MX records. |

dnsenum |

Automated DNS enumeration tool, dictionary attacks, brute-forcing, zone transfers (if allowed). | Discovering subdomains and gathering DNS information efficiently. |

fierce |

DNS reconnaissance and subdomain enumeration tool with recursive search and wildcard detection. | User-friendly interface for DNS reconnaissance, identifying subdomains and potential targets. |

dnsrecon |

Combines multiple DNS reconnaissance techniques and supports various output formats. | Comprehensive DNS enumeration, identifying subdomains, and gathering DNS records for further analysis. |

theHarvester |

OSINT tool that gathers information from various sources, including DNS records (email addresses). | Collecting email addresses, employee information, and other data associated with a domain from multiple sources. |

Online DNS Lookup Services |

User-friendly interfaces for performing DNS lookups. | Quick and easy DNS lookups, convenient when command-line tools are not available, checking for domain availability or basic information |

The dig command (Domain Information Groper) is a versatile and powerful utility for querying DNS servers and retrieving various types of DNS records. Its flexibility and detailed and customizable output make it a go-to choice.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

dig domain.com |

Performs a default A record lookup for the domain. |

dig domain.com A |

Retrieves the IPv4 address (A record) associated with the domain. |

dig domain.com AAAA |

Retrieves the IPv6 address (AAAA record) associated with the domain. |

dig domain.com MX |

Finds the mail servers (MX records) responsible for the domain. |

dig domain.com NS |

Identifies the authoritative name servers for the domain. |

dig domain.com TXT |

Retrieves any TXT records associated with the domain. |

dig domain.com CNAME |

Retrieves the canonical name (CNAME) record for the domain. |

dig domain.com SOA |

Retrieves the start of authority (SOA) record for the domain. |

dig @1.1.1.1 domain.com |

Specifies a specific name server to query; in this case 1.1.1.1 |

dig +trace domain.com |

Shows the full path of DNS resolution. |

dig -x 192.168.1.1 |

Performs a reverse lookup on the IP address 192.168.1.1 to find the associated host name. You may need to specify a name server. |

dig +short domain.com |

Provides a short, concise answer to the query. |

dig +noall +answer domain.com |

Displays only the answer section of the query output. |

dig domain.com ANY |

Retrieves all available DNS records for the domain (Note: Many DNS servers ignore ANY queries to reduce load and prevent abuse, as per RFC 8482). |

Caution: Some servers can detect and block excessive DNS queries. Use caution and respect rate limits. Always obtain permission before performing extensive DNS reconnaissance on a target.

Digging DNS

root@htb[/htb]$ dig google.com

; <<>> DiG 9.18.24-0ubuntu0.22.04.1-Ubuntu <<>> google.com

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 16449

;; flags: qr rd ad; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 0

;; WARNING: recursion requested but not available

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;google.com. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

google.com. 0 IN A 142.251.47.142

;; Query time: 0 msec

;; SERVER: 172.23.176.1#53(172.23.176.1) (UDP)

;; WHEN: Thu Jun 13 10:45:58 SAST 2024

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 54

This output is the result of a DNS query using the dig command for the domain google.com. The command was executed on a system running DiG version 9.18.24-0ubuntu0.22.04.1-Ubuntu. The output can be broken down into four key sections:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 16449: This line indicates the type of query (QUERY), the successful status (NOERROR), and a unique identifier (16449) for this specific query.;; flags: qr rd ad; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 0: This describes the flags in the DNS header:qr: Query Response flag - indicates this is a response.rd: Recursion Desired flag - means recursion was requested.ad: Authentic Data flag - means the resolver considers the data authentic.;; WARNING: recursion requested but not available: This indicates that recursion was requested, but the server does not support it.;google.com. IN A: This line specifies the question: "What is the IPv4 address (A record) for google.com?"google.com. 0 IN A 142.251.47.142: This is the answer to the query. It indicates that the IP address associated with google.com is 142.251.47.142. The '0' represents the TTL (time-to-live), indicating how long the result can be cached before being refreshed.;; Query time: 0 msec: This shows the time it took for the query to be processed and the response to be received (0 milliseconds).;; SERVER: 172.23.176.1#53(172.23.176.1) (UDP): This identifies the DNS server that provided the answer and the protocol used (UDP).;; WHEN: Thu Jun 13 10:45:58 SAST 2024: This is the timestamp of when the query was made.;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 54: This indicates the size of the DNS message received (54 bytes).An opt pseudosection can sometimes exist in a dig query. This is due to Extension Mechanisms for DNS (EDNS), which allows for additional features such as larger message sizes and DNS Security Extensions (DNSSEC) support.

If you just want the answer to the question, without any of the other information, you can query dig using +short:

Digging DNS

root@htb[/htb]$ dig +short hackthebox.com

104.18.20.126

104.18.21.126

When exploring DNS records, we've primarily focused on the main domain (e.g., example.com) and its associated information. However, beneath the surface of this primary domain lies a potential network of subdomains. These subdomains are extensions of the main domain, often created to organise and separate different sections or functionalities of a website. For instance, a company might use blog.example.com for its blog, shop.example.com for its online store, or mail.example.com for its email services.

Subdomains often host valuable information and resources that aren't directly linked from the main website. This can include:

Development and Staging Environments: Companies often use subdomains to test new features or updates before deploying them to the main site. Due to relaxed security measures, these environments sometimes contain vulnerabilities or expose sensitive information.Hidden Login Portals: Subdomains might host administrative panels or other login pages that are not meant to be publicly accessible. Attackers seeking unauthorised access can find these as attractive targets.Legacy Applications: Older, forgotten web applications might reside on subdomains, potentially containing outdated software with known vulnerabilities.Sensitive Information: Subdomains can inadvertently expose confidential documents, internal data, or configuration files that could be valuable to attackers.Subdomain enumeration is the process of systematically identifying and listing these subdomains. From a DNS perspective, subdomains are typically represented by A (or AAAA for IPv6) records, which map the subdomain name to its corresponding IP address. Additionally, CNAME records might be used to create aliases for subdomains, pointing them to other domains or subdomains. There are two main approaches to subdomain enumeration:

This involves directly interacting with the target domain's DNS servers to uncover subdomains. One method is attempting a DNS zone transfer, where a misconfigured server might inadvertently leak a complete list of subdomains. However, due to tightened security measures, this is rarely successful.

A more common active technique is brute-force enumeration, which involves systematically testing a list of potential subdomain names against the target domain. Tools like dnsenum, ffuf, and gobuster can automate this process, using wordlists of common subdomain names or custom-generated lists based on specific patterns.

This relies on external sources of information to discover subdomains without directly querying the target's DNS servers. One valuable resource is Certificate Transparency (CT) logs, public repositories of SSL/TLS certificates. These certificates often include a list of associated subdomains in their Subject Alternative Name (SAN) field, providing a treasure trove of potential targets.

Another passive approach involves utilising search engines like Google or DuckDuckGo. By employing specialised search operators (e.g., site:), you can filter results to show only subdomains related to the target domain.

Additionally, various online databases and tools aggregate DNS data from multiple sources, allowing you to search for subdomains without directly interacting with the target.

Each of these methods has its strengths and weaknesses. Active enumeration offers more control and potential for comprehensive discovery but can be more detectable. Passive enumeration is stealthier but might not uncover all existing subdomains. Combining both approaches provides a more thorough and effective subdomain enumeration strategy.

Subdomain Brute-Force Enumeration is a powerful active subdomain discovery technique that leverages pre-defined lists of potential subdomain names. This approach systematically tests these names against the target domain to identify valid subdomains. By using carefully crafted wordlists, you can significantly increase the efficiency and effectiveness of your subdomain discovery efforts.

The process breaks down into four steps:

Wordlist Selection: The process begins with selecting a wordlist containing potential subdomain names. These wordlists can be:General-Purpose: Containing a broad range of common subdomain names (e.g., dev, staging, blog, mail, admin, test). This approach is useful when you don't know the target's naming conventions.Targeted: Focused on specific industries, technologies, or naming patterns relevant to the target. This approach is more efficient and reduces the chances of false positives.Custom: You can create your own wordlist based on specific keywords, patterns, or intelligence gathered from other sources.Iteration and Querying: A script or tool iterates through the wordlist, appending each word or phrase to the main domain (e.g., example.com) to create potential subdomain names (e.g., dev.example.com, staging.example.com).DNS Lookup: A DNS query is performed for each potential subdomain to check if it resolves to an IP address. This is typically done using the A or AAAA record type.Filtering and Validation: If a subdomain resolves successfully, it's added to a list of valid subdomains. Further validation steps might be taken to confirm the subdomain's existence and functionality (e.g., by attempting to access it through a web browser).There are several tools available that excel at brute-force enumeration:

| Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| dnsenum | Comprehensive DNS enumeration tool that supports dictionary and brute-force attacks for discovering subdomains. |

| fierce | User-friendly tool for recursive subdomain discovery, featuring wildcard detection and an easy-to-use interface. |

| dnsrecon | Versatile tool that combines multiple DNS reconnaissance techniques and offers customisable output formats. |

| amass | Actively maintained tool focused on subdomain discovery, known for its integration with other tools and extensive data sources. |

| assetfinder | Simple yet effective tool for finding subdomains using various techniques, ideal for quick and lightweight scans. |

| puredns | Powerful and flexible DNS brute-forcing tool, capable of resolving and filtering results effectively. |

dnsenum is a versatile and widely-used command-line tool written in Perl. It is a comprehensive toolkit for DNS reconnaissance, providing various functionalities to gather information about a target domain's DNS infrastructure and potential subdomains. The tool offers several key functions:

DNS Record Enumeration: dnsenum can retrieve various DNS records, including A, AAAA, NS, MX, and TXT records, providing a comprehensive overview of the target's DNS configuration.Zone Transfer Attempts: The tool automatically attempts zone transfers from discovered name servers. While most servers are configured to prevent unauthorised zone transfers, a successful attempt can reveal a treasure trove of DNS information.Subdomain Brute-Forcing: dnsenum supports brute-force enumeration of subdomains using a wordlist. This involves systematically testing potential subdomain names against the target domain to identify valid ones.Google Scraping: The tool can scrape Google search results to find additional subdomains that might not be listed in DNS records directly.Reverse Lookup: dnsenum can perform reverse DNS lookups to identify domains associated with a given IP address, potentially revealing other websites hosted on the same server.WHOIS Lookups: The tool can also perform WHOIS queries to gather information about domain ownership and registration details.Let's see dnsenum in action by demonstrating how to enumerate subdomains for our target, inlanefreight.com. In this demonstration, we'll use the subdomains-top1million-5000.txt wordlist from SecLists, which contains the top 5000 most common subdomains.

Code: bash

dnsenum --enum inlanefreight.com -f /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/DNS/subdomains-top1million-110000.txt -r

In this command:

dnsenum --enum inlanefreight.com: We specify the target domain we want to enumerate, along with a shortcut for some tuning options --enum.-f /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/DNS/subdomains-top1million-5000.txt: We indicate the path to the SecLists wordlist we'll use for brute-forcing. Adjust the path if your SecLists installation is different.-r: This option enables recursive subdomain brute-forcing, meaning that if dnsenum finds a subdomain, it will then try to enumerate subdomains of that subdomain.Subdomain Bruteforcing

root@htb[/htb]$ dnsenum --enum inlanefreight.com -f /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/DNS/subdomains-top1million-20000.txt

dnsenum VERSION:1.2.6

----- inlanefreight.com -----

Host's addresses:

__________________

inlanefreight.com. 300 IN A 134.209.24.248

[...]

Brute forcing with /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/DNS/subdomains-top1million-20000.txt:

_______________________________________________________________________________________

www.inlanefreight.com. 300 IN A 134.209.24.248

support.inlanefreight.com. 300 IN A 134.209.24.248

[...]

done.

While brute-forcing can be a fruitful approach, there's a less invasive and potentially more efficient method for uncovering subdomains – DNS zone transfers. This mechanism, designed for replicating DNS records between name servers, can inadvertently become a goldmine of information for prying eyes if misconfigured.

A DNS zone transfer is essentially a wholesale copy of all DNS records within a zone (a domain and its subdomains) from one name server to another. This process is essential for maintaining consistency and redundancy across DNS servers. However, if not adequately secured, unauthorised parties can download the entire zone file, revealing a complete list of subdomains, their associated IP addresses, and other sensitive DNS data.

Zone Transfer Request (AXFR): The secondary DNS server initiates the process by sending a zone transfer request to the primary server. This request typically uses the AXFR (Full Zone Transfer) type.SOA Record Transfer: Upon receiving the request (and potentially authenticating the secondary server), the primary server responds by sending its Start of Authority (SOA) record. The SOA record contains vital information about the zone, including its serial number, which helps the secondary server determine if its zone data is current.DNS Records Transmission: The primary server then transfers all the DNS records in the zone to the secondary server, one by one. This includes records like A, AAAA, MX, CNAME, NS, and others that define the domain's subdomains, mail servers, name servers, and other configurations.Zone Transfer Complete: Once all records have been transmitted, the primary server signals the end of the zone transfer. This notification informs the secondary server that it has received a complete copy of the zone data.Acknowledgement (ACK): The secondary server sends an acknowledgement message to the primary server, confirming the successful receipt and processing of the zone data. This completes the zone transfer process.While zone transfers are essential for legitimate DNS management, a misconfigured DNS server can transform this process into a significant security vulnerability. The core issue lies in the access controls governing who can initiate a zone transfer.

In the early days of the internet, allowing any client to request a zone transfer from a DNS server was common practice. This open approach simplified administration but opened a gaping security hole. It meant that anyone, including malicious actors, could ask a DNS server for a complete copy of its zone file, which contains a wealth of sensitive information.

The information gleaned from an unauthorised zone transfer can be invaluable to an attacker. It reveals a comprehensive map of the target's DNS infrastructure, including:

Subdomains: A complete list of subdomains, many of which might not be linked from the main website or easily discoverable through other means. These hidden subdomains could host development servers, staging environments, administrative panels, or other sensitive resources.IP Addresses: The IP addresses associated with each subdomain, providing potential targets for further reconnaissance or attacks.Name Server Records: Details about the authoritative name servers for the domain, revealing the hosting provider and potential misconfigurations.Fortunately, awareness of this vulnerability has grown, and most DNS server administrators have mitigated the risk. Modern DNS servers are typically configured to allow zone transfers only to trusted secondary servers, ensuring that sensitive zone data remains confidential.

However, misconfigurations can still occur due to human error or outdated practices. This is why attempting a zone transfer (with proper authorisation) remains a valuable reconnaissance technique. Even if unsuccessful, the attempt can reveal information about the DNS server's configuration and security posture.

Exploiting Zone Transfers

You can use the dig command to request a zone transfer:

DNS Zone Transfers

root@htb[/htb]$ dig axfr @nsztm1.digi.ninja zonetransfer.me

This command instructs dig to request a full zone transfer (axfr) from the DNS server responsible for zonetransfer.me. If the server is misconfigured and allows the transfer, you'll receive a complete list of DNS records for the domain, including all subdomains.

DNS Zone Transfers

root@htb[/htb]$ dig axfr @nsztm1.digi.ninja zonetransfer.me

; <<>> DiG 9.18.12-1~bpo11+1-Debian <<>> axfr @nsztm1.digi.ninja zonetransfer.me

; (1 server found)

;; global options: +cmd

zonetransfer.me. 7200 IN SOA nsztm1.digi.ninja. robin.digi.ninja. 2019100801 172800 900 1209600 3600

zonetransfer.me. 300 IN HINFO "Casio fx-700G" "Windows XP"

zonetransfer.me. 301 IN TXT "google-site-verification=tyP28J7JAUHA9fw2sHXMgcCC0I6XBmmoVi04VlMewxA"

zonetransfer.me. 7200 IN MX 0 ASPMX.L.GOOGLE.COM.

...

zonetransfer.me. 7200 IN A 5.196.105.14

zonetransfer.me. 7200 IN NS nsztm1.digi.ninja.

zonetransfer.me. 7200 IN NS nsztm2.digi.ninja.

_acme-challenge.zonetransfer.me. 301 IN TXT "6Oa05hbUJ9xSsvYy7pApQvwCUSSGgxvrbdizjePEsZI"

_sip._tcp.zonetransfer.me. 14000 IN SRV 0 0 5060 www.zonetransfer.me.

14.105.196.5.IN-ADDR.ARPA.zonetransfer.me. 7200 IN PTR www.zonetransfer.me.

asfdbauthdns.zonetransfer.me. 7900 IN AFSDB 1 asfdbbox.zonetransfer.me.

asfdbbox.zonetransfer.me. 7200 IN A 127.0.0.1

asfdbvolume.zonetransfer.me. 7800 IN AFSDB 1 asfdbbox.zonetransfer.me.

canberra-office.zonetransfer.me. 7200 IN A 202.14.81.230

...

;; Query time: 10 msec

;; SERVER: 81.4.108.41#53(nsztm1.digi.ninja) (TCP)

;; WHEN: Mon May 27 18:31:35 BST 2024

;; XFR size: 50 records (messages 1, bytes 2085)

zonetransfer.me is a service specifically setup to demonstrate the risks of zone transfers so that the dig command will return the full zone record.

Once the DNS directs traffic to the correct server, the web server configuration becomes crucial in determining how the incoming requests are handled. Web servers like Apache, Nginx, or IIS are designed to host multiple websites or applications on a single server. They achieve this through virtual hosting, which allows them to differentiate between domains, subdomains, or even separate websites with distinct content.

At the core of virtual hosting is the ability of web servers to distinguish between multiple websites or applications sharing the same IP address. This is achieved by leveraging the HTTP Host header, a piece of information included in every HTTP request sent by a web browser.

The key difference between VHosts and subdomains is their relationship to the Domain Name System (DNS) and the web server's configuration.

Subdomains: These are extensions of a main domain name (e.g., blog.example.com is a subdomain of example.com). Subdomains typically have their own DNS records, pointing to either the same IP address as the main domain or a different one. They can be used to organise different sections or services of a website.Virtual Hosts (VHosts): Virtual hosts are configurations within a web server that allow multiple websites or applications to be hosted on a single server. They can be associated with top-level domains (e.g., example.com) or subdomains (e.g., dev.example.com). Each virtual host can have its own separate configuration, enabling precise control over how requests are handled.If a virtual host does not have a DNS record, you can still access it by modifying the hosts file on your local machine. The hosts file allows you to map a domain name to an IP address manually, bypassing DNS resolution.

Websites often have subdomains that are not public and won't appear in DNS records. These subdomains are only accessible internally or through specific configurations. VHost fuzzing is a technique to discover public and non-public subdomains and VHosts by testing various hostnames against a known IP address.

Virtual hosts can also be configured to use different domains, not just subdomains. For example:

Code: apacheconf

# Example of name-based virtual host configuration in Apache

<VirtualHost *:80>

ServerName www.example1.com

DocumentRoot /var/www/example1

</VirtualHost>

<VirtualHost *:80>

ServerName www.example2.org

DocumentRoot /var/www/example2

</VirtualHost>

<VirtualHost *:80>

ServerName www.another-example.net

DocumentRoot /var/www/another-example

</VirtualHost>

Here, example1.com, example2.org, and another-example.net are distinct domains hosted on the same server. The web server uses the Host header to serve the appropriate content based on the requested domain name.

The following illustrates the process of how a web server determines the correct content to serve based on the Host header:

Browser Requests a Website: When you enter a domain name (e.g., www.inlanefreight.com) into your browser, it initiates an HTTP request to the web server associated with that domain's IP address.Host Header Reveals the Domain: The browser includes the domain name in the request's Host header, which acts as a label to inform the web server which website is being requested.Web Server Determines the Virtual Host: The web server receives the request, examines the Host header, and consults its virtual host configuration to find a matching entry for the requested domain name.Serving the Right Content: Upon identifying the correct virtual host configuration, the web server retrieves the corresponding files and resources associated with that website from its document root and sends them back to the browser as the HTTP response.In essence, the Host header functions as a switch, enabling the web server to dynamically determine which website to serve based on the domain name requested by the browser.

There are three primary types of virtual hosting, each with its advantages and drawbacks:

Name-Based Virtual Hosting: This method relies solely on the HTTP Host header to distinguish between websites. It is the most common and flexible method, as it doesn't require multiple IP addresses. It’s cost-effective, easy to set up, and supports most modern web servers. However, it requires the web server to support name-based virtual hosting and can have limitations with certain protocols like SSL/TLS.IP-Based Virtual Hosting: This type of hosting assigns a unique IP address to each website hosted on the server. The server determines which website to serve based on the IP address to which the request was sent. It doesn't rely on the Host header, can be used with any protocol, and offers better isolation between websites. Still, it requires multiple IP addresses, which can be expensive and less scalable.Port-Based Virtual Hosting: Different websites are associated with different ports on the same IP address. For example, one website might be accessible on port 80, while another is on port 8080. Port-based virtual hosting can be used when IP addresses are limited, but it’s not as common or user-friendly as name-based virtual hosting and might require users to specify the port number in the URL.While manual analysis of HTTP headers and reverse DNS lookups can be effective, specialised virtual host discovery tools automate and streamline the process, making it more efficient and comprehensive. These tools employ various techniques to probe the target server and uncover potential virtual hosts.

Several tools are available to aid in the discovery of virtual hosts:

| Tool | Description | Features |

|---|---|---|

| gobuster | A multi-purpose tool often used for directory/file brute-forcing, but also effective for virtual host discovery. | Fast, supports multiple HTTP methods, can use custom wordlists. |

| Feroxbuster | Similar to Gobuster, but with a Rust-based implementation, known for its speed and flexibility. | Supports recursion, wildcard discovery, and various filters. |

| ffuf | Another fast web fuzzer that can be used for virtual host discovery by fuzzing the Host header. |

Customizable wordlist input and filtering options. |

Gobuster is a versatile tool commonly used for directory and file brute-forcing, but it also excels at virtual host discovery. It systematically sends HTTP requests with different Host headers to a target IP address and then analyses the responses to identify valid virtual hosts.

There are a couple of things you need to prepare to brute force Host headers:

Target Identification: First, identify the target web server's IP address. This can be done through DNS lookups or other reconnaissance techniques.Wordlist Preparation: Prepare a wordlist containing potential virtual host names. You can use a pre-compiled wordlist, such as SecLists, or create a custom one based on your target's industry, naming conventions, or other relevant information.The gobuster command to bruteforce vhosts generally looks like this:

Virtual Hosts

root@htb[/htb]$ gobuster vhost -u http://<target_IP_address> -w <wordlist_file> --append-domain