.png)

In computer science, the terms Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are often used interchangeably, leading to confusion. While closely related, they represent distinct concepts with specific applications and theoretical underpinnings.

.png)

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a broad field focused on developing intelligent systems capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence. These tasks include understanding natural language, recognizing objects, making decisions, solving problems, and learning from experience. AI systems exhibit cognitive abilities like reasoning, perception, and problem-solving across various domains. Some key areas of AI include:

Natural Language Processing (NLP): Enabling computers to understand, interpret, and generate human language.Computer Vision: Allowing computers to "see" and interpret images and videos.Robotics: Developing robots that can perform tasks autonomously or with human guidance.Expert Systems: Creating systems that mimic the decision-making abilities of human experts.One of the primary goals of AI is to augment human capabilities, not just replace human efforts. AI systems are designed to enhance human decision-making and productivity, providing support in complex data analysis, prediction, and mechanical tasks.

AI solves complex problems in many diverse domains like healthcare, finance, and cybersecurity. For example:

AI improves disease diagnosis and drug discovery.AI detects fraudulent transactions and optimizes investment strategies.AI identifies and mitigates cyber threats.Machine Learning (ML) is a subfield of AI that focuses on enabling systems to learn from data and improve their performance on specific tasks without explicit programming. ML algorithms use statistical techniques to identify patterns, trends, and anomalies within datasets, allowing the system to make predictions, decisions, or classifications based on new input data.

ML can be categorized into three main types:

Supervised Learning: The algorithm learns from labeled data, where each data point is associated with a known outcome or label. Examples include:Unsupervised Learning: The algorithm learns from unlabeled data without providing an outcome or label. Examples include:Reinforcement Learning: The algorithm learns through trial and error by interacting with an environment and receiving feedback as rewards or penalties. Examples include:

For instance, an ML algorithm can be trained on a dataset of images labeled as "cat" or "dog." By analyzing the features and patterns in these images, the algorithm learns to distinguish between cats and dogs. When presented with a new image, it can predict whether it depicts a cat or a dog based on its learned knowledge.

ML has a wide range of applications across various industries, including:

Healthcare: Disease diagnosis, drug discovery, personalized medicineFinance: Fraud detection, risk assessment, algorithmic tradingMarketing: Customer segmentation, targeted advertising, recommendation systemsCybersecurity: Threat detection, intrusion prevention, malware analysisTransportation: Traffic prediction, autonomous vehicles, route optimizationML is a rapidly evolving field with new algorithms, techniques, and applications emerging. It is a crucial enabler of AI, providing the learning and adaptation capabilities that underpin many intelligent systems.

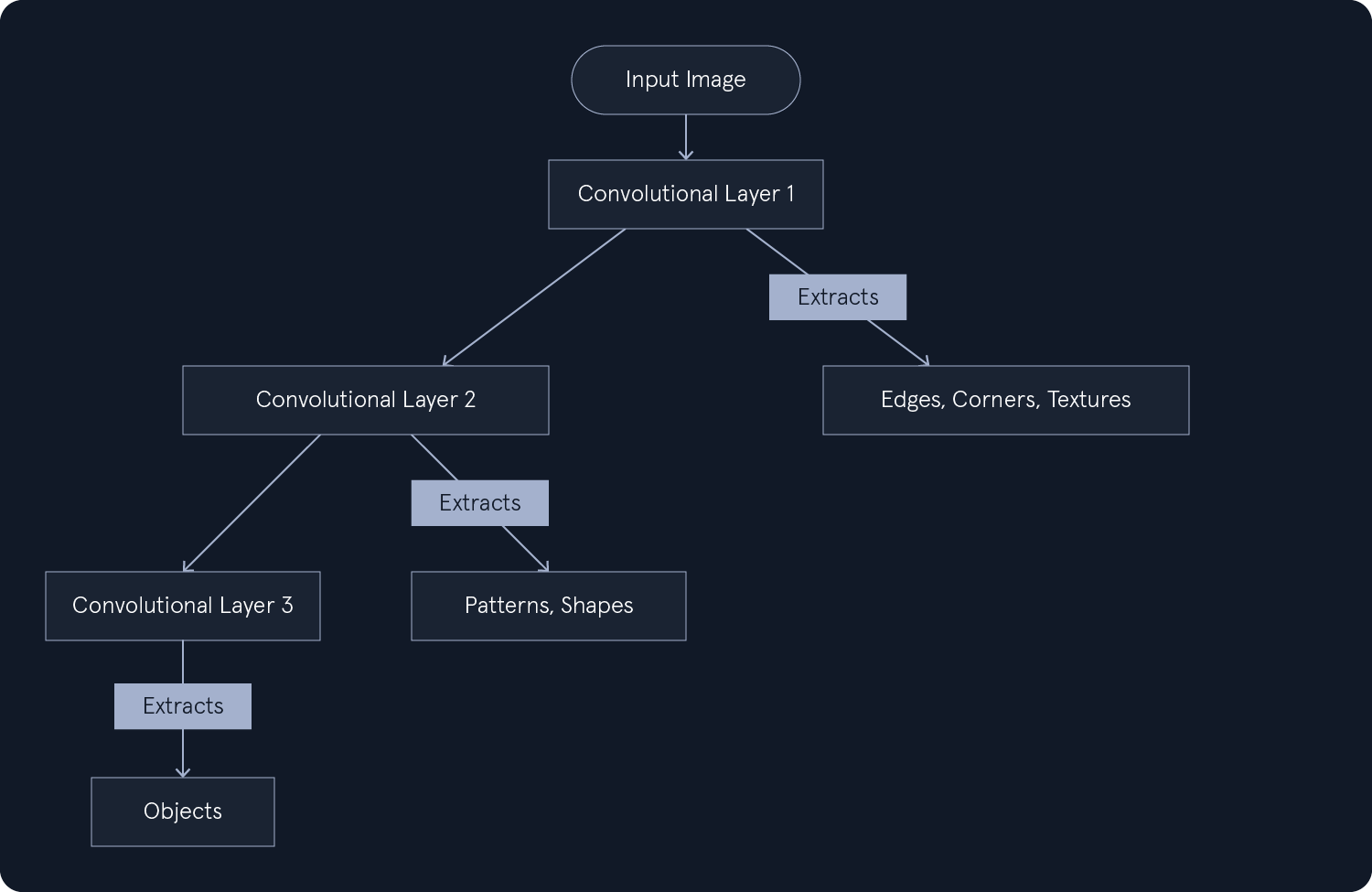

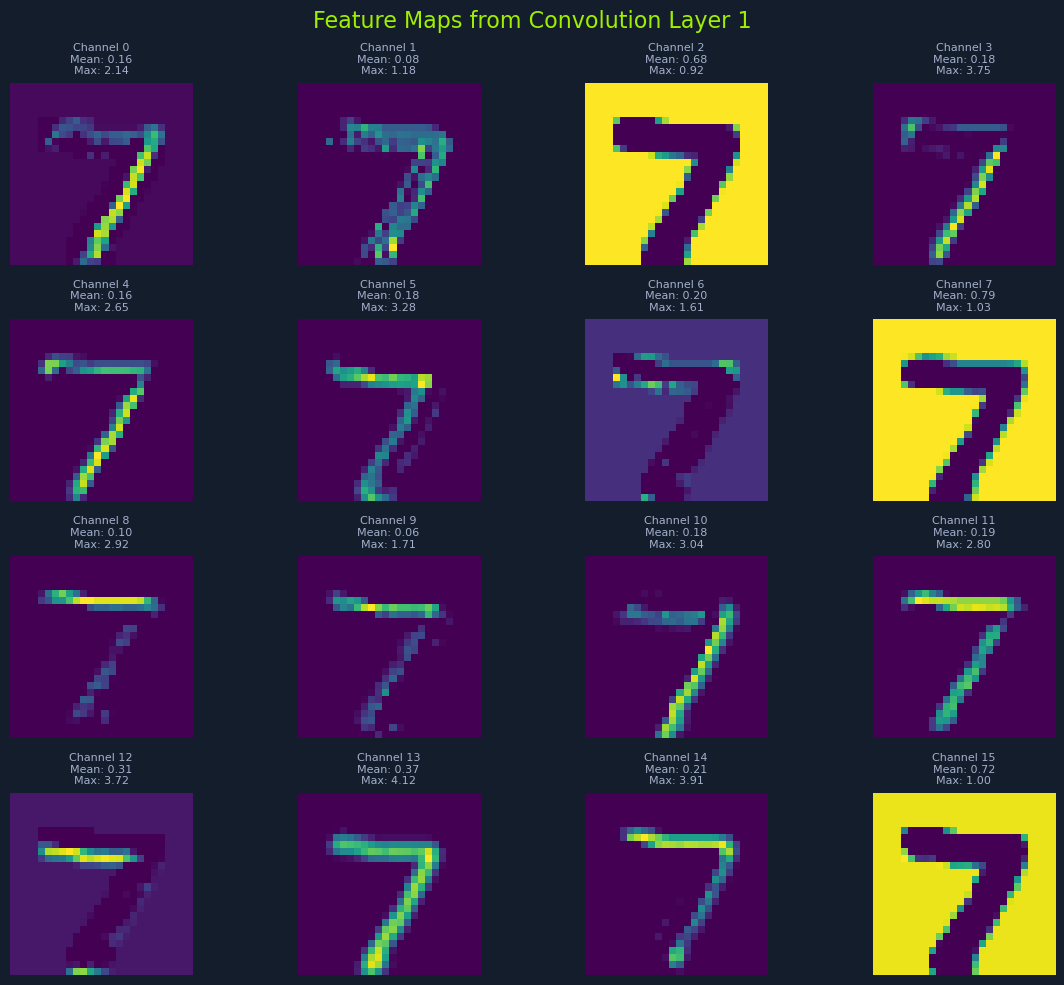

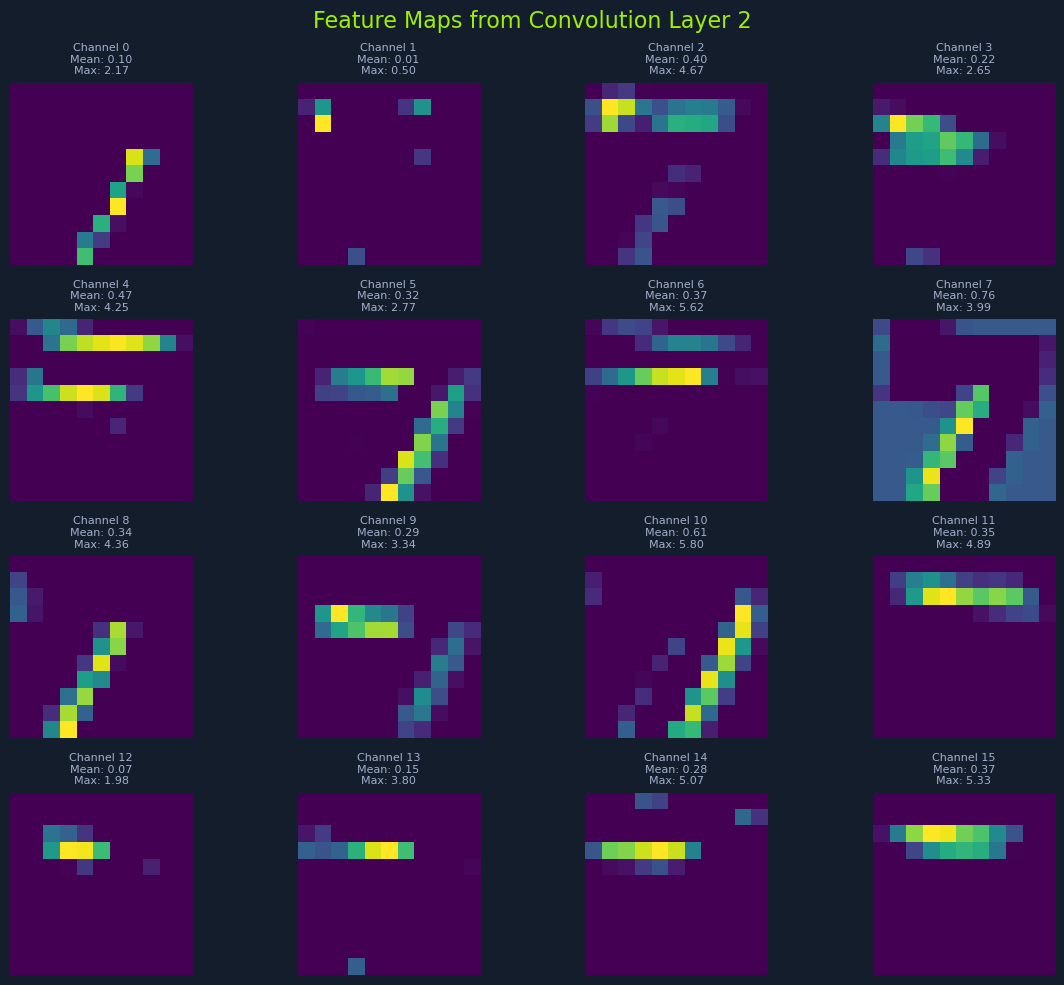

Deep Learning (DL) is a subfield of ML that uses neural networks with multiple layers to learn and extract features from complex data. These deep neural networks can automatically identify intricate patterns and representations within large datasets, making them particularly powerful for tasks involving unstructured or high-dimensional data, such as images, audio, and text.

Key characteristics of DL include:

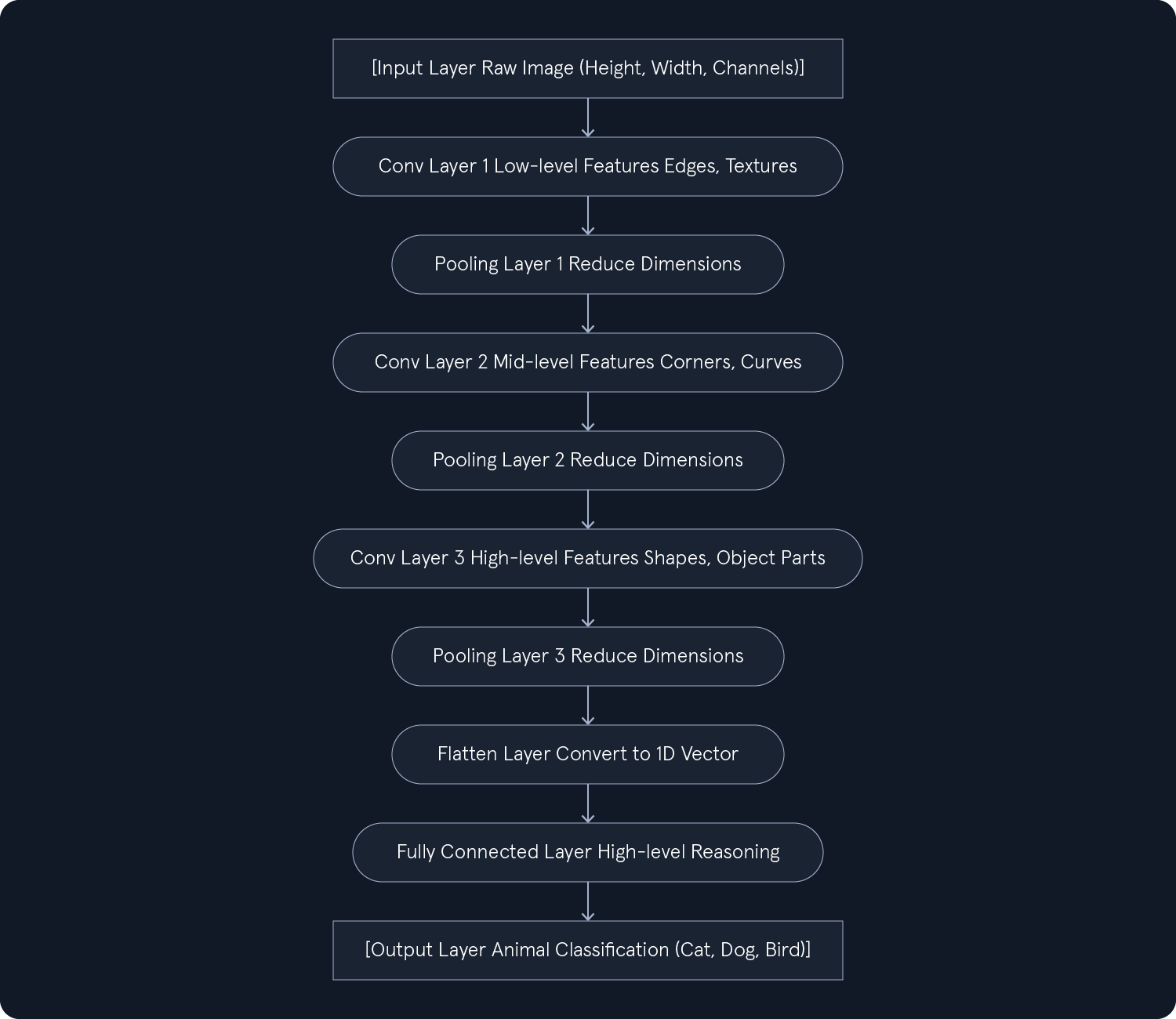

Hierarchical Feature Learning: DL models can learn hierarchical data representations, where each layer captures increasingly abstract features. For example, lower layers might detect edges and textures in image recognition, while higher layers identify more complex structures like shapes and objects.End-to-End Learning: DL models can be trained end-to-end, meaning they can directly map raw input data to desired outputs without manual feature engineering.Scalability: DL models can scale well with large datasets and computational resources, making them suitable for big data applications.Common types of neural networks used in DL include:

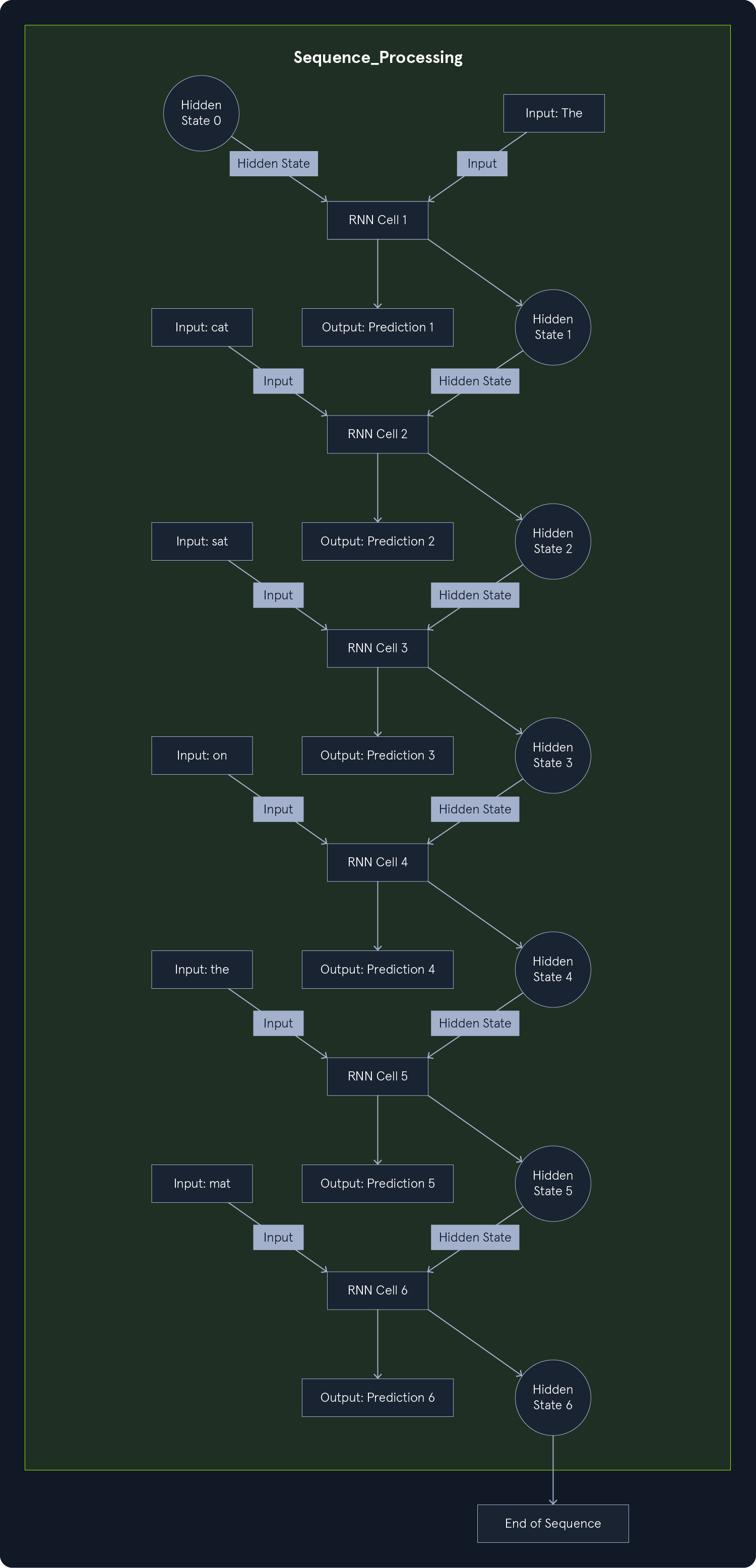

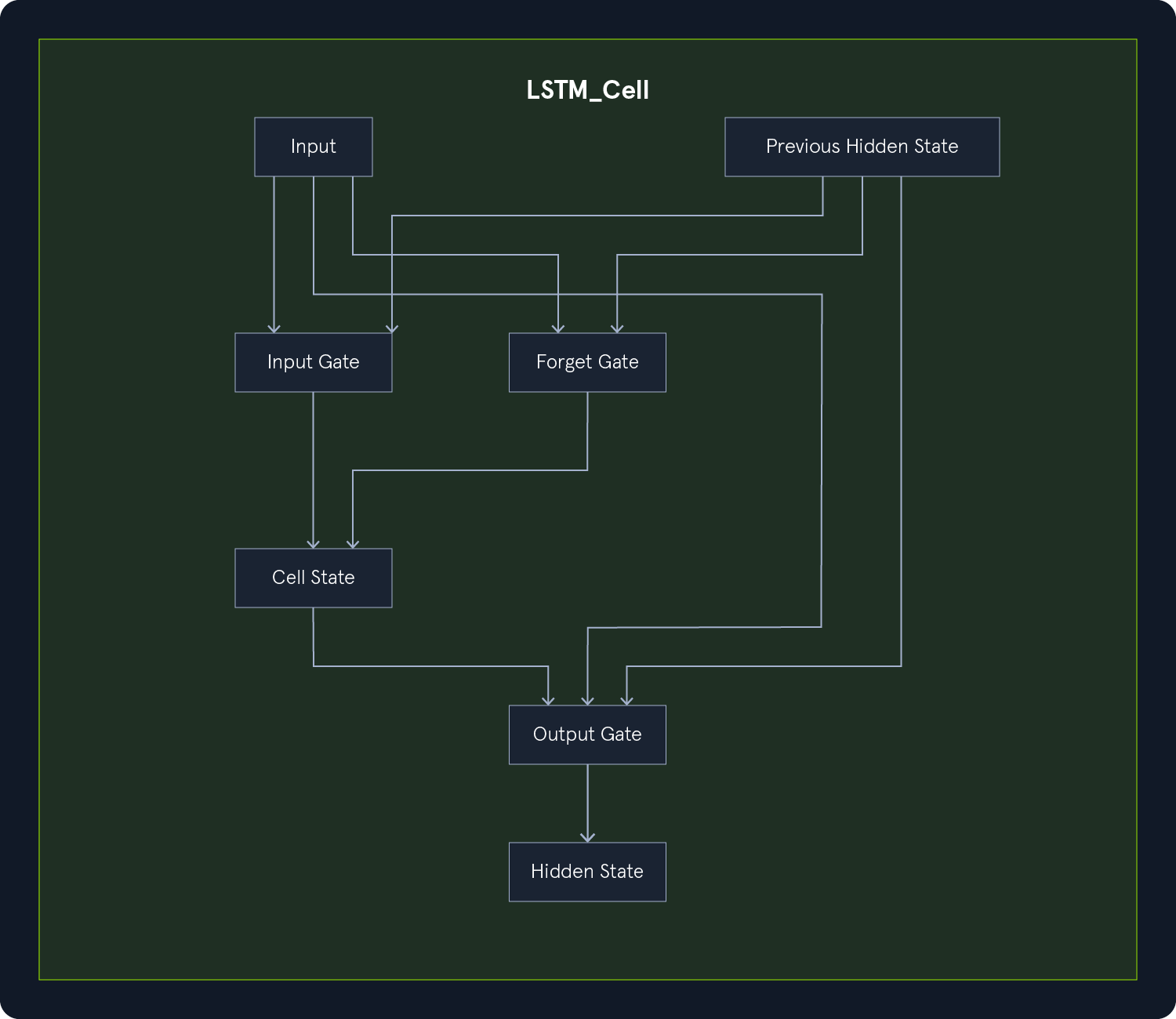

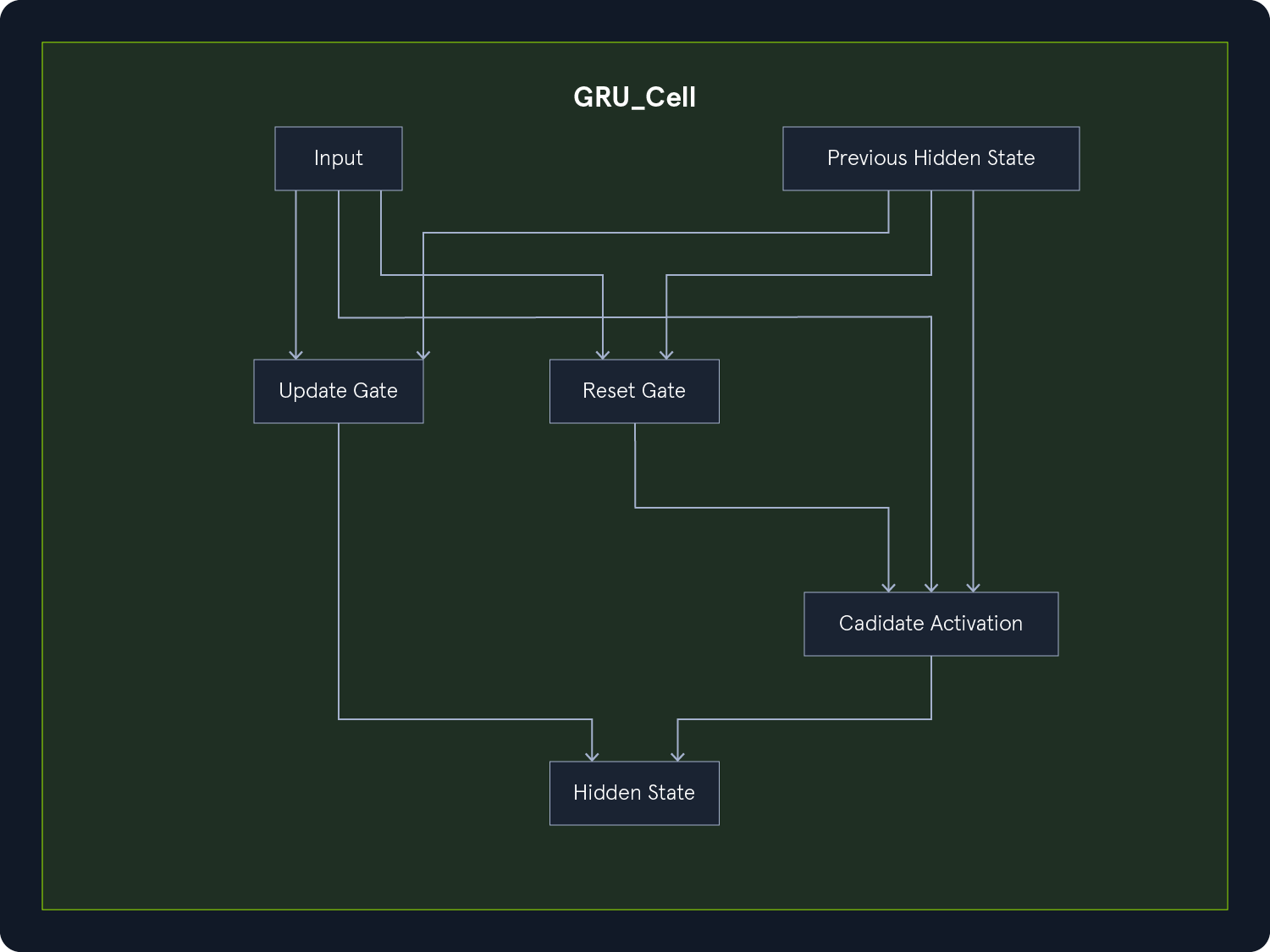

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): Specialized for image and video data, CNNs use convolutional layers to detect local patterns and spatial hierarchies.Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs): Designed for sequential data like text and speech, RNNs have loops that allow information to persist across time steps.Transformers: A recent advancement in DL, transformers are particularly effective for natural language processing tasks. They leverage self-attention mechanisms to handle long-range dependencies.DL has revolutionized many areas of AI, achieving state-of-the-art performance in tasks such as:

Computer Vision: Image classification, object detection, image segmentationNatural Language Processing (NLP): Sentiment analysis, machine translation, text generationSpeech Recognition: Transcribing audio to text, speech synthesisReinforcement Learning: Training agents for complex tasks like playing games and controlling robotsMachine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) are subfields of Artificial Intelligence (AI) that enable systems to learn from data and make intelligent decisions. They are crucial enablers of AI, providing the learning and adaptation capabilities that underpin many intelligent systems.

ML algorithms, including DL algorithms, allow machines to learn from data, recognize patterns, and make decisions. The various types of ML, such as supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning, each contribute to achieving AI's broader goals. For instance:

Computer Vision, supervised learning algorithms and Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) enable machines to "see" and interpret images accurately.Natural Language Processing (NLP), traditional ML algorithms and advanced DL models like transformers allow for understanding and generating human language, enabling applications like chatbots and translation services.DL has significantly enhanced the capabilities of ML by providing powerful tools for feature extraction and representation learning, particularly in domains with complex, unstructured data.

The synergy between ML, DL, and AI is evident in their collaborative efforts to solve complex problems. For example:

Autonomous Driving, a combination of ML and DL techniques processes sensor data, recognizes objects, and makes real-time decisions, enabling vehicles to navigate safely.Robotics, reinforcement learning algorithms, often enhanced with DL, train robots to perform complex tasks in dynamic environments.ML and DL fuel AI's ability to learn, adapt, and evolve, driving progress across various domains and enhancing human capabilities. The synergy between these fields is essential for advancing the frontiers of AI and unlocking new levels of innovation and productivity.

As mentioned, this module delves into some mathematical concepts behind the algorithms and processes. If you come across symbols or notations that are unfamiliar, feel free to refer back to this page for a quick refresher. You don't need to understand everything here; it's primarily meant to serve as a reference.

*)The multiplication operator denotes the product of two numbers or expressions. For example:

Code: python

3 * 4 = 12

/)The division operator denotes dividing one number or expression by another. For example:

Code: python

10 / 2 = 5

+)The addition operator represents the sum of two or more numbers or expressions. For example:

Code: python

5 + 3 = 8

-)The subtraction operator represents the difference between two numbers or expressions. For example:

Code: python

9 - 4 = 5

x_t)The subscript notation represents a variable indexed by t, often indicating a specific time step or state in a sequence. For example:

Code: python

x_t = q(x_t | x_{t-2})

This notation is commonly used in sequences and time series data, where each x_t represents the value of x at time t.

x^n)Superscript notation is used to denote exponents or powers. For example:

Code: python

x^2 = x * x

This notation is used in polynomial expressions and exponential functions.

||...||)The norm measures the size or length of a vector. The most common norm is the Euclidean norm, which is calculated as follows:

Code: python

||v|| = sqrt{v_1^2 + v_2^2 + ... + v_n^2}

Other norms include the L1 norm (Manhattan distance) and the L∞ norm (maximum absolute value):

Code: python

||v||_1 = |v_1| + |v_2| + ... + |v_n|

||v||_∞ = max(|v_1|, |v_2|, ..., |v_n|)

Norms are used in various applications, such as measuring the distance between vectors, regularizing models to prevent overfitting, and normalizing data.

Σ)The summation symbol indicates the sum of a sequence of terms. For example:

Code: python

Σ_{i=1}^{n} a_i

This represents the sum of the terms a_1, a_2, ..., a_n. Summation is used in many mathematical formulas, including calculating means, variances, and series.

log2(x))The logarithm base 2 is the logarithm of x with base 2, often used in information theory to measure entropy. For example:

Code: python

log2(8) = 3

Logarithms are used in information theory, cryptography, and algorithms for their properties in reducing large numbers and handling exponential growth.

ln(x))The natural logarithm is the logarithm of x with base e (Euler's number). For example:

Code: python

ln(e^2) = 2

Due to its smooth and continuous nature, the natural logarithm is widely used in calculus, differential equations, and probability theory.

e^x)The exponential function represents Euler's number e raised to the power of x. For example:

Code: python

e^{2} ≈ 7.389

The exponential function is used to model growth and decay processes, probability distributions (e.g., the normal distribution), and various mathematical and physical models.

2^x)The exponential function (base 2) represents 2 raised to the power of x, often used in binary systems and information metrics. For example:

Code: python

2^3 = 8

This function is used in computer science, particularly in binary representations and information theory.

A * v)Matrix-vector multiplication denotes the product of a matrix A and a vector v. For example:

Code: python

A * v = [ [1, 2], [3, 4] ] * [5, 6] = [17, 39]

This operation is fundamental in linear algebra and is used in various applications, including transforming vectors, solving systems of linear equations, and in neural networks.

A * B)Matrix-matrix multiplication denotes the product of two matrices A and B. For example:

Code: python

A * B = [ [1, 2], [3, 4] ] * [ [5, 6], [7, 8] ] = [ [19, 22], [43, 50] ]

This operation is used in linear transformations, solving systems of linear equations, and deep learning for operations between layers.

A^T)The transpose of a matrix A is denoted by A^T and swaps the rows and columns of A. For example:

Code: python

A = [ [1, 2], [3, 4] ]

A^T = [ [1, 3], [2, 4] ]

The transpose is used in various matrix operations, such as calculating the dot product and preparing data for certain algorithms.

A^{-1})The inverse of a matrix A is denoted by A^{-1} and is the matrix that, when multiplied by A, results in the identity matrix. For example:

Code: python

A = [ [1, 2], [3, 4] ]

A^{-1} = [ [-2, 1], [1.5, -0.5] ]

The inverse is used to solve systems of linear equations, inverting transformations, and various optimization problems.

det(A))The determinant of a square matrix A is a scalar value that can be computed and is used in various matrix operations. For example:

Code: python

A = [ [1, 2], [3, 4] ]

det(A) = 1 * 4 - 2 * 3 = -2

The determinant determines whether a matrix is invertible (non-zero determinant) in calculating volumes, areas, and geometric transformations.

tr(A))The trace of a square matrix A is the sum of the elements on the main diagonal. For example:

Code: python

A = [ [1, 2], [3, 4] ]

tr(A) = 1 + 4 = 5

The trace is used in various matrix properties and in calculating eigenvalues.

|S|)The cardinality represents the number of elements in a set S. For example:

Code: python

S = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

|S| = 5

Cardinality is used in counting elements, probability calculations, and various combinatorial problems.

∪)The union of two sets A and B is the set of all elements in either A or B or both. For example:

Code: python

A = {1, 2, 3}, B = {3, 4, 5}

A ∪ B = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

The union is used in combining sets, data merging, and in various set operations.

∩)The intersection of two sets A and B is the set of all elements in both A and B. For example:

Code: python

A = {1, 2, 3}, B = {3, 4, 5}

A ∩ B = {3}

The intersection finds common elements, data filtering, and various set operations.

A^c)The complement of a set A is the set of all elements not in A. For example:

Code: python

U = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}, A = {1, 2, 3}

A^c = {4, 5}

The complement is used in set operations, probability calculations, and various logical operations.

>=)The greater than or equal to operator indicates that the value on the left is either greater than or equal to the value on the right. For example:

Code: python

a >= b

<=)The less than or equal to operator indicates that the value on the left is either less than or equal to the value on the right. For example:

a <= b

==)The equality operator checks if two values are equal. For example:

a == b

!=)The inequality operator checks if two values are not equal. For example:

Code: python

a != b

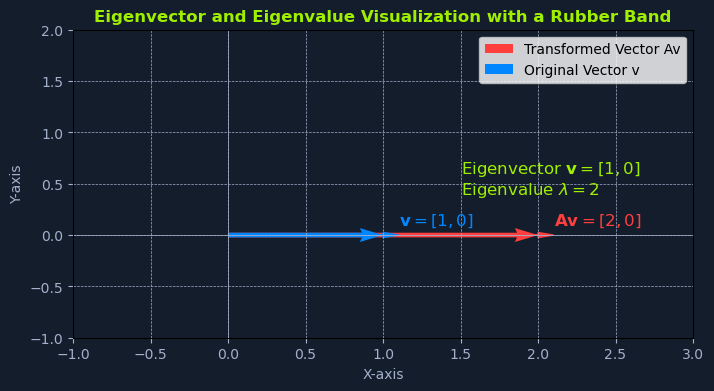

λ)The lambda symbol often represents an eigenvalue in linear algebra or a scalar parameter in equations. For example:

Code: python

A * v = λ * v, where λ = 3

Eigenvalues are used to understand the behavior of linear transformations, principal component analysis (PCA), and various optimization problems.

An eigenvector is a non-zero vector that, when multiplied by a matrix, results in a scalar multiple of itself. The scalar is the eigenvalue. For example:

Code: python

A * v = λ * v

Eigenvectors are used to understand the directions of maximum variance in data, dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA, and various machine learning algorithms.

max(...))The maximum function returns the largest value from a set of values. For example:

Code: python

max(4, 7, 2) = 7

The maximum function is used in optimization, finding the best solution, and in various decision-making processes.

min(...))The minimum function returns the smallest value from a set of values. For example:

Code: python

min(4, 7, 2) = 2

The minimum function is used in optimization, finding the best solution, and in various decision-making processes.

1 / ...)The reciprocal represents one divided by an expression, effectively inverting the value. For example:

Code: python

1 / x where x = 5 results in 0.2

The reciprocal is used in various mathematical operations, such as calculating rates and proportions.

...)The ellipsis indicates the continuation of a pattern or sequence, often used to denote an indefinite or ongoing process. For example:

Code: python

a_1 + a_2 + ... + a_n

The ellipsis is used in mathematical notation to represent sequences and series.

f(x))Function notation represents a function f applied to an input x. For example:

Code: python

f(x) = x^2 + 2x + 1

Function notation is used in defining mathematical relationships, modeling real-world phenomena, and in various algorithms.

P(x | y))The conditional probability distribution denotes the probability distribution of x given y. For example:

Code: python

P(Output | Input)

Conditional probabilities are used in Bayesian inference, decision-making under uncertainty, and various probabilistic models.

E[...])The expectation operator represents a random variable's expected value or average over its probability distribution. For example:

Code: python

E[X] = sum x_i P(x_i)

The expectation is used in calculating the mean, decision-making under uncertainty, and various statistical models.

Var(X))Variance measures the spread of a random variable X around its mean. It is calculated as follows:

Code: python

Var(X) = E[(X - E[X])^2]

The variance is used to understand the dispersion of data, assess risk, and use various statistical models.

σ(X))Standard Deviation is the square root of the variance and provides a measure of the dispersion of a random variable. For example:

Code: python

σ(X) = sqrt(Var(X))

Standard deviation is used to understand the spread of data, assess risk, and use various statistical models.

Cov(X, Y))Covariance measures how two random variables X and Y vary. It is calculated as follows:

Code: python

Cov(X, Y) = E[(X - E[X])(Y - E[Y])]

Covariance is used to understand the relationship between two variables, portfolio optimization, and various statistical models.

ρ(X, Y))The correlation is a normalized covariance measure, ranging from -1 to 1. It indicates the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two random variables. For example:

Code: python

ρ(X, Y) = Cov(X, Y) / (σ(X) * σ(Y))

Correlation is used to understand the linear relationship between variables in data analysis and in various statistical models.

Supervised learning algorithms form the cornerstone of many Machine Learning (ML) applications, enabling systems to learn from labeled data and make accurate predictions. Each data point is associated with a known outcome or label in supervised learning. Think of it as having a set of examples with the correct answers already provided.

The algorithm aims to learn a mapping function to predict the label for new, unseen data. This process involves identifying patterns and relationships between the features (input variables) and the corresponding labels (output variables), allowing the algorithm to generalize its knowledge to new instances.

Imagine you're teaching a child to identify different fruits. You show them an apple and say, "This is an apple." You then show them an orange and say, "This is an orange." By repeatedly presenting examples with labels, the child learns to distinguish between the fruits based on their characteristics, such as color, shape, and size.

Supervised learning algorithms work similarly. They are fed with a large dataset of labeled examples, and they use this data to train a model that can predict the labels for new, unseen examples. The training process involves adjusting the model's parameters to minimize the difference between its predictions and the actual labels.

Supervised learning problems can be broadly categorized into two main types:

Classification: In classification problems, the goal is to predict a categorical label. For example, classifying emails as spam or not or identifying images of cats, dogs, or birds.Regression: In regression problems, the goal is to predict a continuous value. For example, one could predict the price of a house based on its size, location, and other features or forecast the stock market.Understanding supervised learning's core concepts is essential for effectively grasping it. These concepts form the building blocks for comprehending how algorithms learn from labeled data to make accurate predictions.

Training data is the foundation of supervised learning. It is the labeled dataset used to train the ML model. This dataset consists of input features and their corresponding output labels. The quality and quantity of training data significantly impact the model's accuracy and ability to generalize to new, unseen data.

Think of training data as a set of example problems with their correct solutions. The algorithm learns from these examples to develop a model that can solve similar problems in the future.

Features are the measurable properties or characteristics of the data that serve as input to the model. They are the variables that the algorithm uses to learn and make predictions. Selecting relevant features is crucial for building an effective model.

For example, when predicting house prices, features might include:

Labels are the known outcomes or target variables associated with each data point in the training set. They represent the "correct answers" that the model aims to predict.

In the house price prediction example, the label would be the actual price of the house.

A model is a mathematical representation of the relationship between the features and the labels. It is learned from the training data and used to predict new, unseen data. The model can be considered a function that takes the features as input and outputs a prediction for the label.

Training is the process of feeding the training data to the algorithm and adjusting the model's parameters to minimize prediction errors. The algorithm learns from the training data by iteratively adjusting its internal parameters to improve its prediction accuracy.

Once the model is trained, it can be used to predict new, unseen data. This involves providing the model with the features of the new data point, and the model will output a prediction for the label. Prediction is a specific application of inference, focusing on generating actionable outputs such as classifying an email as spam or forecasting stock prices.

Inference is a broader concept that encompasses prediction but also includes understanding the underlying structure and patterns in the data. It involves using a trained model to derive insights, estimate parameters, and understand relationships between variables.

For example, inference might involve determining which features are most important in a decision tree, estimating the coefficients in a linear regression model, or analyzing how different inputs impact the model's predictions. While prediction emphasizes actionable outputs, inference often focuses on explaining and interpreting the results.

Evaluation is a critical step in supervised learning. It involves assessing the model's performance to determine its accuracy and generalization ability to new data. Common evaluation metrics include:

Accuracy: The proportion of correct predictions made by the model.Precision: The proportion of true positive predictions among all positive predictions.Recall: The proportion of true positive predictions among all actual positive instances.F1-score: A harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced measure of the model's performance.Generalization refers to the model's ability to accurately predict outcomes for new, unseen data not used during training. A model that generalizes well can effectively apply its learned knowledge to real-world scenarios.

Overfitting occurs when a model learns the training data too well, including noise and outliers. This can lead to poor generalization of new data, as the model has memorized the training set instead of learning the underlying patterns.

Underfitting occurs when a model is too simple to capture the underlying patterns in the data. This results in poor performance on both the training data and new, unseen data.

Cross-validation is a technique used to assess how well a model will generalize to an independent dataset. It involves splitting the data into multiple subsets (folds) and training the model on different combinations of these folds while validating it on the remaining fold. This helps reduce overfitting and provides a more reliable estimate of the model's performance.

Regularization is a technique used to prevent overfitting by adding a penalty term to the loss function. This penalty discourages the model from learning overly complex patterns that might not generalize well. Common regularization techniques include:

L1 Regularization: Adds a penalty equal to the absolute value of the magnitude of coefficients.L2 Regularization: Adds a penalty equal to the square of the magnitude of coefficients.

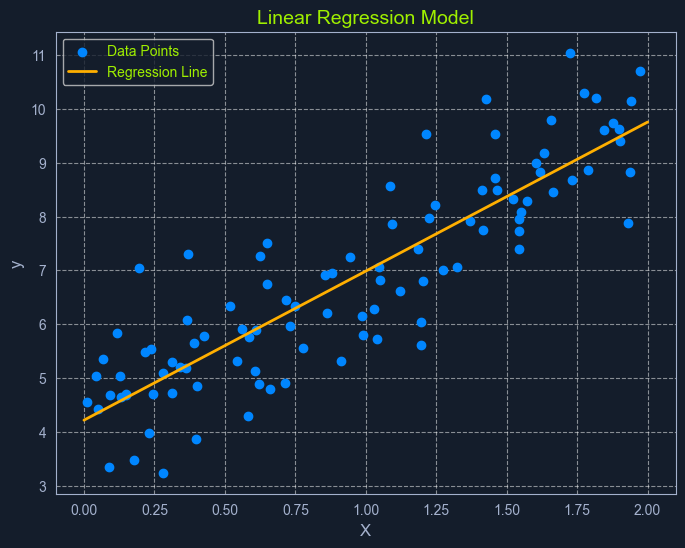

Linear Regression is a fundamental supervised learning algorithm that predicts a continuous target variable by establishing a linear relationship between the target and one or more predictor variables. The algorithm models this relationship using a linear equation, where changes in the predictor variables result in proportional changes in the target variable. The goal is to find the best-fitting line that minimizes the sum of the squared differences between the predicted values and the actual values.

Imagine you're trying to predict a house's price based on size. Linear regression would attempt to find a straight line that best captures the relationship between these two variables. As the size of the house increases, the price generally tends to increase. Linear regression quantifies this relationship, allowing us to predict the price of a house given its size.

Before diving into linear regression, it's essential to understand the broader concept of regression in machine learning. Regression analysis is a type of supervised learning where the goal is to predict a continuous target variable. This target variable can take on any value within a given range. Think of it as estimating a number instead of classifying something into categories (which is what classification algorithms do).

Examples of regression problems include:

In all these cases, the output we're trying to predict is a continuous value. This is what distinguishes regression from classification, where the output is a categorical label (e.g., "spam" or "not spam").

Now, with that clarified, let's revisit linear regression. It's simply one specific type of regression analysis where we assume a linear relationship between the predictor variables and the target variable. This means we try to model the relationship using a straight line.

In its simplest form, simple linear regression involves one predictor variable and one target variable. A linear equation represents the relationship between them:

Code: python

y = mx + c

Where:

y is the predicted target variablex is the predictor variablem is the slope of the line (representing the relationship between x and y)c is the y-intercept (the value of y when x is 0)The algorithm aims to find the optimal values for m and c that minimize the error between the predicted y values and the actual y values in the training data. This is typically done using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), which aims to minimize the sum of squared errors.

When multiple predictor variables are involved, it's called multiple linear regression. The equation becomes:

Code: python

y = b0 + b1x1 + b2x2 + ... + bnxn

Where:

y is the predicted target variablex1, x2, ..., xn are the predictor variablesb0 is the y-interceptb1, b2, ..., bn are the coefficients representing the relationship between each predictor variable and the target variable.

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) is a common method for estimating the optimal values for the coefficients in linear regression. It aims to minimize the sum of the squared differences between the actual values and the values predicted by the model.

Think of it as finding the line that minimizes the total area of the squares formed between the data points and the line. This "line of best fit" represents the relationship that best describes the data.

Here's a breakdown of the OLS process:

Calculate Residuals: For each data point, the residual is the difference between the actual y value and the y value predicted by the model.Square the Residuals: Each residual is squared to ensure that all values are positive and to give more weight to larger errors.Sum the Squared Residuals: All the squared residuals are summed to get a single value representing the model's overall error. This sum is called the Residual Sum of Squares (RSS).Minimize the Sum of Squared Residuals: The algorithm adjusts the coefficients to find the values that result in the smallest possible RSS.This process can be visualized as finding the line that minimizes the total area of the squares formed between the data points and the line.

Linear regression relies on several key assumptions about the data:

Linearity: A linear relationship exists between the predictor and target variables.Independence: The observations in the dataset are independent of each other.Homoscedasticity: The variance of the errors is constant across all levels of the predictor variables. This means the spread of the residuals should be roughly the same across the range of predicted values.Normality: The errors are normally distributed. This assumption is important for making valid inferences about the model's coefficients.Assessing these assumptions before applying linear regression ensures the model's validity and reliability. If these assumptions are violated, the model's predictions may be inaccurate or misleading.

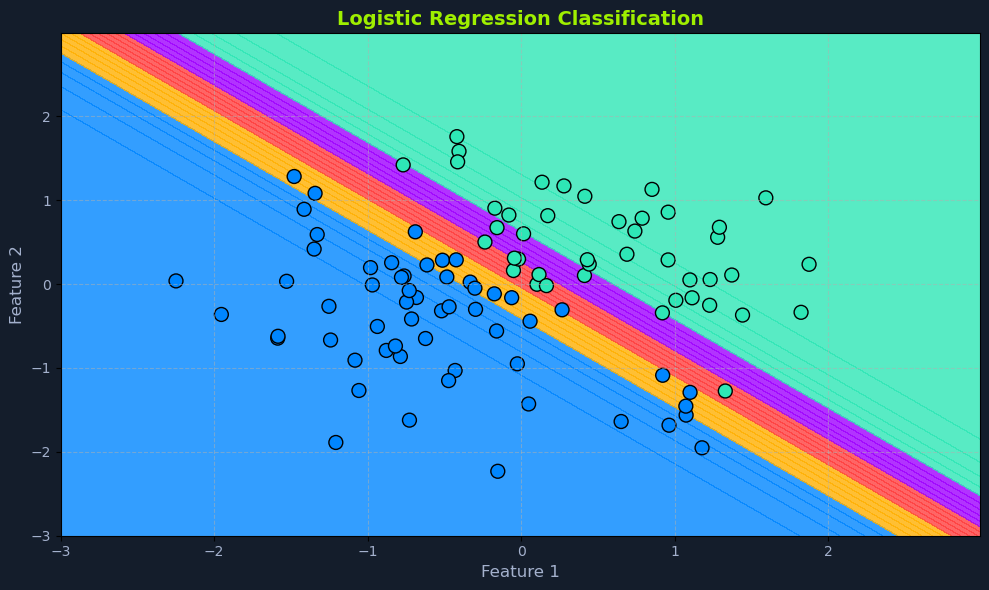

Despite its name, logistic regression is a supervised learning algorithm primarily used for classification, not regression. It predicts a categorical target variable with two possible outcomes (binary classification). These outcomes are typically represented as binary values (e.g., 0 or 1, true or false, yes or no).

For example, logistic regression can predict whether an email is spam or not or whether a customer will click on an ad. The algorithm models the probability of the target variable belonging to a particular class using a logistic function, which maps the input features to a value between 0 and 1.

Before we delve deeper into logistic regression, let's clarify what classification means in machine learning. Classification is a type of supervised learning that aims to assign data points to specific categories or classes. Unlike regression, which predicts a continuous value, classification predicts a discrete label.

Examples of classification problems include:

In all these cases, the output we're trying to predict is a category or class label.

Unlike linear regression, which outputs a continuous value, logistic regression outputs a probability score between 0 and 1. This score represents the likelihood of the input belonging to the positive class (typically denoted as '1').

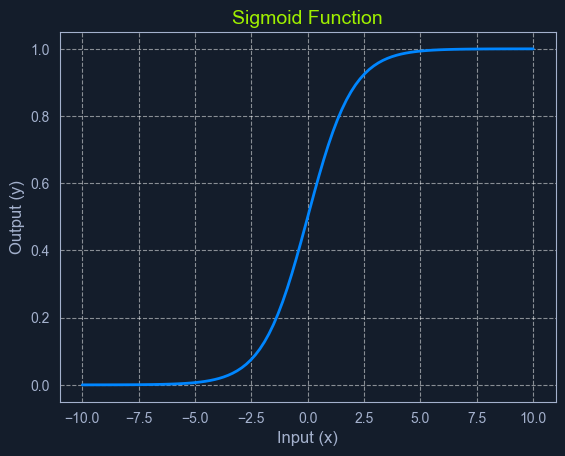

It achieves this by employing a sigmoid function, which maps any input value (a linear combination of features) to a value within the 0 to 1 range. This function introduces non-linearity, allowing the model to capture complex relationships between the features and the probability of the outcome.

The sigmoid function is a mathematical function that takes any input value (ranging from negative to positive infinity) and maps it to an output value between 0 and 1. This makes it particularly useful for modeling probabilities.

The sigmoid function has a characteristic "S" shape, hence its name. It starts with low values for negative inputs, then rapidly increases around zero, and finally plateaus at high values for positive ones. This smooth, gradual transition between 0 and 1 allows it to represent the probability of an event occurring.

In logistic regression, the sigmoid function transforms the linear combination of input features into a probability score. This score represents the likelihood of the input belonging to the positive class.

The sigmoid function's mathematical representation is:

Code: python

P(x) = 1 / (1 + e^-z)

Where:

P(x) is the predicted probability.e is the base of the natural logarithm (approximately 2.718).z is the linear combination of input features and their weights, similar to the linear regression equation: z = m1x1 + m2x2 + ... + mnxn + cLet's say we're building a spam filter using logistic regression. The algorithm would analyze various email features, such as the sender's address, the presence of certain keywords, and the email's content, to calculate a probability score. The email will be classified as spam if the score exceeds a predefined threshold (e.g., 0.8).

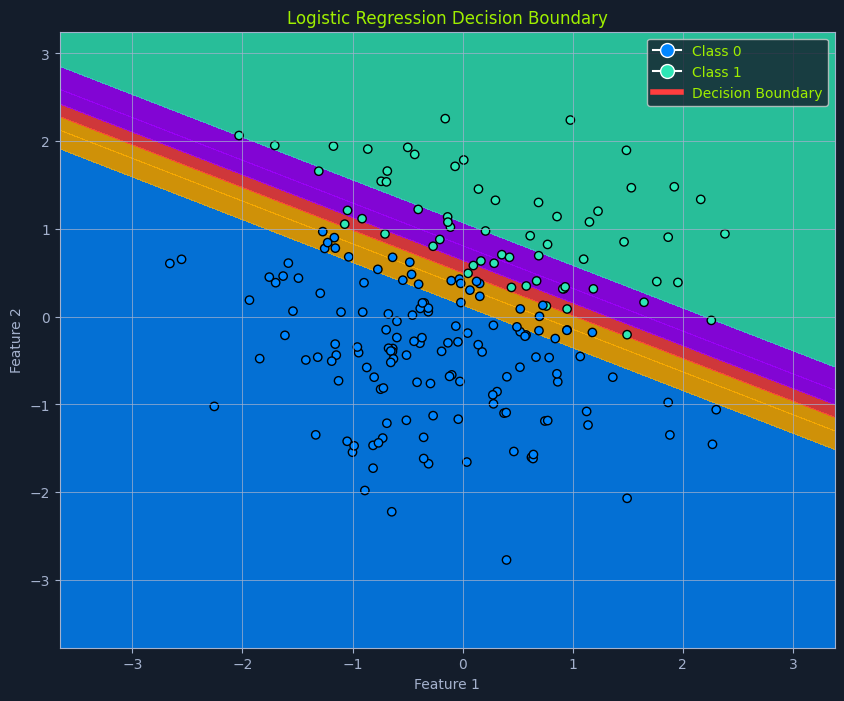

A crucial aspect of logistic regression is the decision boundary. In a simplified scenario with two features, imagine a line separating the data points into two classes. This separator is the decision boundary, determined by the model's learned parameters and the chosen threshold probability.

In higher dimensions with more features, this separator becomes a hyperplane. The decision boundary defines the cutoff point for classifying an instance into one class or another.

In the context of machine learning, a hyperplane is a subspace whose dimension is one less than that of the ambient space. It's a way to visualize a decision boundary in higher dimensions.

Think of it this way:

Moving to higher dimensions (with more than three features) makes it difficult to visualize, but the concept remains the same. A hyperplane is a "flat" subspace that divides the higher-dimensional space into two regions.

In logistic regression, the hyperplane is defined by the model's learned parameters (coefficients) and the chosen threshold probability. It acts as the decision boundary, separating data points into classes based on their predicted probabilities.

The threshold probability is often set at 0.5 but can be adjusted depending on the specific problem and the desired balance between true and false positives.

P(x) falls above the threshold, the instance is classified as the positive class.P(x) falls below the threshold, it's classified as the negative class.For example, in spam detection, if the model predicts an email has a 0.8 probability of being spam (and the threshold is 0.5), it's classified as spam. Adjusting the threshold to 0.6 would require a higher probability for the email to be classified as spam.

While not as strict as linear regression, logistic regression does have some underlying assumptions about the data:

Binary Outcome: The target variable must be categorical, with only two possible outcomes.Linearity of Log Odds: It assumes a linear relationship between the predictor variables and the log-odds of the outcome. Log odds are a transformation of probability, representing the logarithm of the odds ratio (the probability of an event occurring divided by the probability of it not occurring).No or Little Multicollinearity: Ideally, there should be little to no multicollinearity among the predictor variables. Multicollinearity occurs when predictor variables are highly correlated, making it difficult to determine their individual effects on the outcome.Large Sample Size: Logistic regression performs better with larger datasets, allowing for more reliable parameter estimation.Assessing these assumptions before applying logistic regression helps ensure the model's accuracy and reliability. Techniques like data exploration, visualization, and statistical tests can be used to evaluate these assumptions.

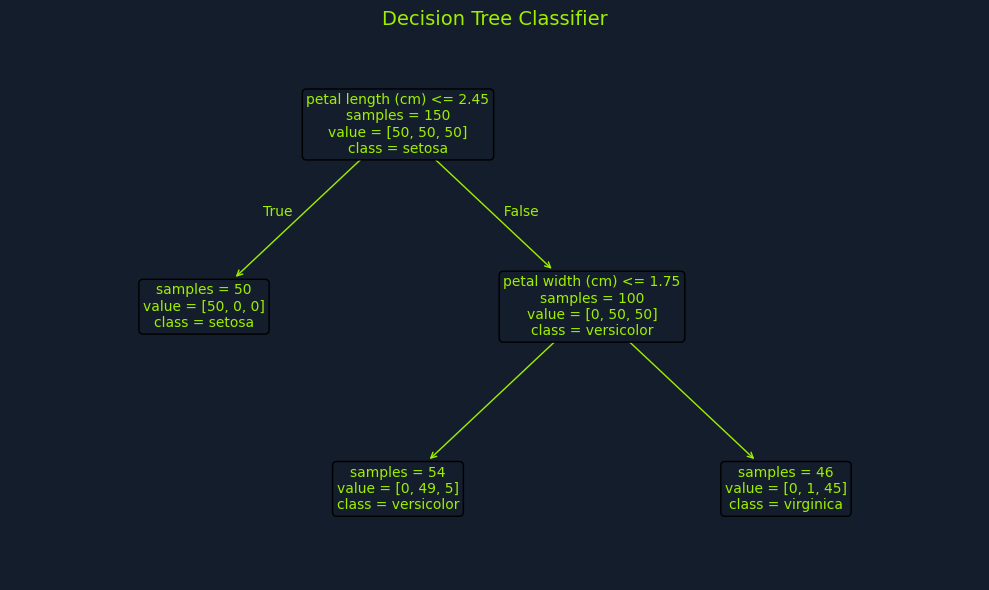

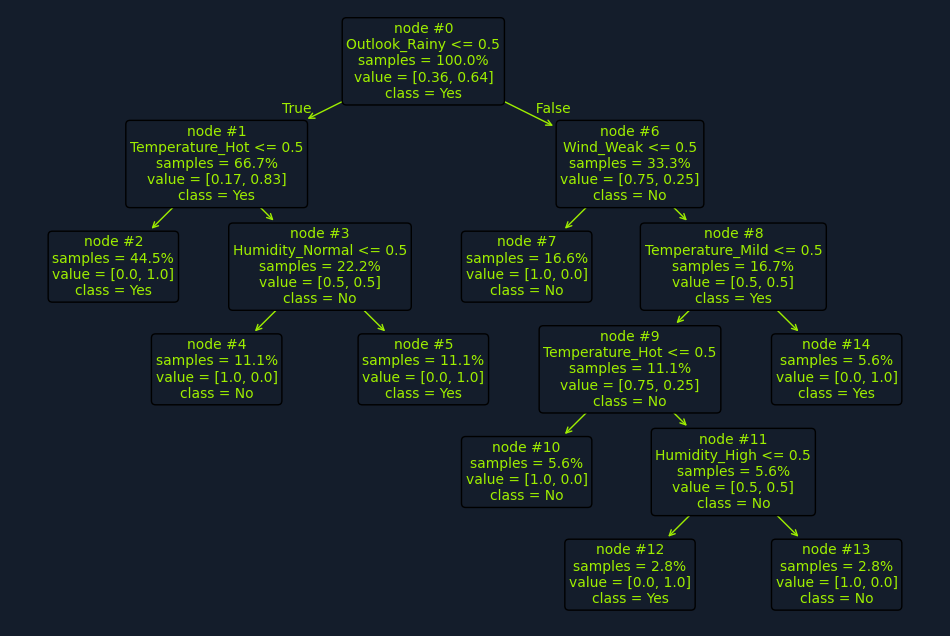

Decision trees are a popular supervised learning algorithm for classification and regression tasks. They are known for their intuitive tree-like structure, which makes them easy to understand and interpret. In essence, a decision tree creates a model that predicts the value of a target variable by learning simple decision rules inferred from the data features.

Imagine you're trying to decide whether to play tennis based on the weather. A decision tree would break down this decision into a series of simple questions: Is it sunny? Is it windy? Is it humid? Based on the answers to these questions, the tree would lead you to a final decision: play tennis or don't play tennis.

A decision tree comprises three main components:

Root Node: This represents the starting point of the tree and contains the entire dataset.Internal Nodes: These nodes represent features or attributes of the data. Each internal node branches into two or more child nodes based on different decision rules.Leaf Nodes: These are the terminal nodes of the tree, representing the final outcome or prediction.Building a decision tree involves selecting the best feature to split the data at each node. This selection is based on measures like Gini impurity, entropy, or information gain, which quantify the homogeneity of the subsets resulting from the split. The goal is to create splits that result in increasingly pure subsets, where the data points within each subset belong predominantly to the same class.

Gini impurity measures the probability of misclassifying a randomly chosen element from a set. A lower Gini impurity indicates a more pure set. The formula for Gini impurity is:

Gini(S) = 1 - Σ (pi)^2

Where:

S is the dataset.pi is the proportion of elements belonging to class i in the set.Consider a dataset S with two classes: A and B. Suppose there are 30 instances of class A and 20 instances of class B in the dataset.

A: pA = 30 / (30 + 20) = 0.6B: pB = 20 / (30 + 20) = 0.4The Gini impurity for this dataset is:

Gini(S) = 1 - (0.6^2 + 0.4^2) = 1 - (0.36 + 0.16) = 1 - 0.52 = 0.48

Entropy measures the disorder or uncertainty in a set. A lower entropy indicates a more homogenous set. The formula for entropy is:

Entropy(S) = - Σ pi * log2(pi)

Where:

S is the dataset.pi is the proportion of elements belonging to class i in the set.Using the same dataset S with 30 instances of class A and 20 instances of class B:

A: pA = 0.6B: pB = 0.4The entropy for this dataset is:

Entropy(S) = - (0.6 * log2(0.6) + 0.4 * log2(0.4))

= - (0.6 * (-0.73697) + 0.4 * (-1.32193))

= - (-0.442182 - 0.528772)

= 0.970954

Information gain measures the reduction in entropy achieved by splitting a set based on a particular feature. The feature with the highest information gain is chosen for the split. The formula for information gain is:

Information Gain(S, A) = Entropy(S) - Σ ((|Sv| / |S|) * Entropy(Sv))

Where:

S is the dataset.A is the feature used for splitting.Sv is the subset of S for which feature A has value v.Consider a dataset S with 50 instances and two classes: A and B. Suppose we consider a feature F that can take on two values: 1 and 2. The distribution of the dataset is as follows:

F = 1: 30 instances, 20 class A, 10 class BF = 2: 20 instances, 10 class A, 10 class BFirst, calculate the entropy of the entire dataset S:

Entropy(S) = - (30/50 * log2(30/50) + 20/50 * log2(20/50))

= - (0.6 * log2(0.6) + 0.4 * log2(0.4))

= - (0.6 * (-0.73697) + 0.4 * (-1.32193))

= 0.970954

Next, calculate the entropy for each subset Sv:

F = 1:A: pA = 20/30 = 0.6667B: pB = 10/30 = 0.3333- (0.6667 * log2(0.6667) + 0.3333 * log2(0.3333)) = 0.9183F = 2:A: pA = 10/20 = 0.5B: pB = 10/20 = 0.5- (0.5 * log2(0.5) + 0.5 * log2(0.5)) = 1.0Now, calculate the weighted average entropy of the subsets:

Weighted Entropy = (|S1| / |S|) * Entropy(S1) + (|S2| / |S|) * Entropy(S2)

= (30/50) * 0.9183 + (20/50) * 1.0

= 0.55098 + 0.4

= 0.95098

Finally, calculate the information gain:

Information Gain(S, F) = Entropy(S) - Weighted Entropy

= 0.970954 - 0.95098

= 0.019974

The tree starts with the root node and selects the feature that best splits the data based on one of these criteria (Gini impurity, entropy, or information gain). This feature becomes the internal node, and branches are created for each possible value or range of values of that feature. The data is then divided into subsets based on these branches. This process continues recursively for each subset until a stopping criterion is met.

The tree stops growing when one of the following conditions is satisfied:

Maximum Depth : The tree reaches a specified maximum depth, preventing it from becoming overly complex and potentially overfitting the data.Minimum Number of Data Points : The number of data points in a node falls below a specified threshold, ensuring that the splits are meaningful and not based on very small subsets.Pure Nodes : All data points in a node belong to the same class, indicating that further splits would not improve the purity of the subsets.

Let's examine the "Playing Tennis" example more closely to illustrate how a decision tree works in practice.

Imagine you have a dataset of historical weather conditions and whether you played tennis on those days. For example:

| PlayTennis | Outlook_Overcast | Outlook_Rainy | Outlook_Sunny | Temperature_Cool | Temperature_Hot | Temperature_Mild | Humidity_High | Humidity_Normal | Wind_Strong | Wind_Weak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | False | True | False | True | False | False | False | True | False | True |

| Yes | False | False | True | False | True | False | False | True | False | True |

| No | False | True | False | True | False | False | True | False | True | False |

| No | False | True | False | False | True | False | True | False | False | True |

| Yes | False | False | True | False | False | True | False | True | False | True |

| Yes | False | False | True | False | True | False | False | True | False | True |

| No | False | True | False | False | True | False | True | False | True | False |

| Yes | True | False | False | True | False | False | True | False | False | True |

| No | False | True | False | False | True | False | False | True | True | False |

| No | False | True | False | False | True | False | True | False | True | False |

The dataset includes the following features:

Outlook: Sunny, Overcast, RainyTemperature: Hot, Mild, CoolHumidity: High, NormalWind: Weak, StrongThe target variable is Play Tennis: Yes or No.

A decision tree algorithm would analyze this dataset to identify the features that best separate the "Yes" instances from the "No" instances. It would start by calculating each feature's information gain or Gini impurity to determine which provides the most informative split.

For instance, the algorithm might find that the Outlook feature provides the highest information gain. This means splitting the data based on whether sunny, overcast, or rainy leads to the most significant reduction in entropy or impurity.

The root node of the decision tree would then be the Outlook feature, with three branches: Sunny, Overcast, and Rainy. Based on these branches, the dataset would be divided into three subsets.

Next, the algorithm would analyze each subset to determine the best feature for the next split. For example, in the "Sunny" subset, Humidity might provide the highest information gain. This would lead to another internal node with High and Normal branches.

This process continues recursively until a stopping criterion is met, such as reaching a maximum depth or a minimum number of data points in a node. The final result is a tree-like structure with decision rules at each internal node and predictions (Play Tennis: Yes or No) at the leaf nodes.

One of the advantages of decision trees is that they have minimal assumptions about the data:

No Linearity Assumption: Decision trees can handle linear and non-linear relationships between features and the target variable. This makes them more flexible than algorithms like linear regression, which assume a linear relationship.No Normality Assumption: The data does not need to be normally distributed. This contrasts some statistical methods that require normality for valid inferences.Handles Outliers: Decision trees are relatively robust to outliers. Since they partition the data based on feature values rather than relying on distance-based calculations, outliers are less likely to have a significant impact on the tree structure.These minimal assumptions contribute to decision trees' versatility, allowing them to be applied to a wide range of datasets and problems without extensive preprocessing or transformations.

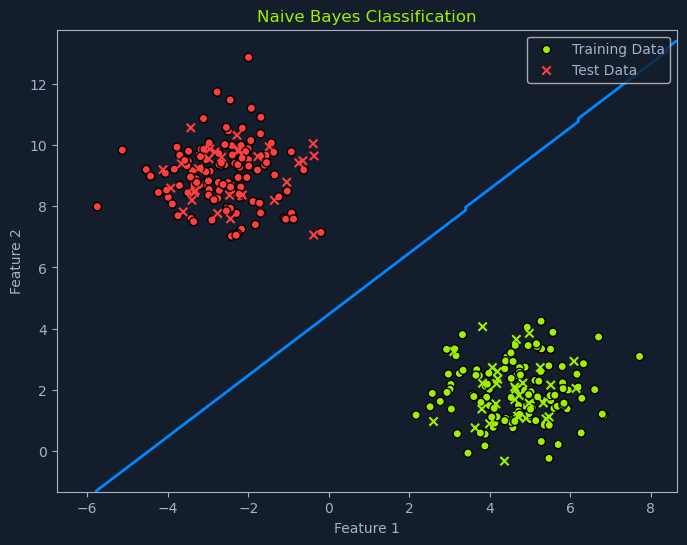

Naive Bayes is a probabilistic algorithm used for classification tasks. It's based on Bayes' theorem, a fundamental concept in probability theory that describes the probability of an event based on prior knowledge and observed evidence. Naive Bayes is a popular choice for tasks like spam filtering and sentiment analysis due to its simplicity, efficiency, and surprisingly good performance in many real-world scenarios.

Before diving into Naive Bayes, let's understand its core concept: Bayes' theorem. This theorem provides a way to update our beliefs about an event based on new evidence. It allows us to calculate the probability of an event, given that another event has already occurred.

It's mathematically represented as:

Code: python

P(A|B) = [P(B|A) * P(A)] / P(B)

Where:

P(A|B): The posterior probability of event A happening, given that event B has already happened.P(B|A): The likelihood of event B happening given that event A has already happened.P(A): The prior probability of event A happening.P(B): The prior probability of event B happening.Let's say we want to know the probability of someone having a disease (A) given that they tested positive for it (B). Bayes' theorem allows us to calculate this probability using the prior probability of having the disease (P(A)), the likelihood of testing positive given that the person has the disease (P(B|A)), and the overall probability of testing positive (P(B)).

Suppose we have the following information:

P(A) = 0.01.P(B|A) = 0.95.P(B), can be calculated using the law of total probability.First, let's calculate P(B):

Code: python

P(B) = P(B|A) * P(A) + P(B|¬A) * P(¬A)

Where:

P(¬A): The probability of not having the disease, which is 1 - P(A) = 0.99.P(B|¬A): The probability of testing positive given that the person does not have the disease, which is the false positive rate, 0.05.Now, substitute the values:

Code: python

P(B) = (0.95 * 0.01) + (0.05 * 0.99)

= 0.0095 + 0.0495

= 0.059

Next, we use Bayes' theorem to find P(A|B):

Code: python

P(A|B) = [P(B|A) * P(A)] / P(B)

= (0.95 * 0.01) / 0.059

= 0.0095 / 0.059

≈ 0.161

So, the probability of someone having the disease, given that they tested positive, is approximately 16.1%.

This example demonstrates how Bayes' theorem can be used to update our beliefs about the likelihood of an event based on new evidence. In this case, even though the test is quite accurate, the low prevalence of the disease means that a positive test result still has a relatively low probability of indicating the actual presence of the disease.

The Naive Bayes classifier leverages Bayes' theorem to predict the probability of a data point belonging to a particular class given its features. To do this, it makes the "naive" assumption of conditional independence among the features. This means it assumes that the presence or absence of one feature doesn't affect the presence or absence of any other feature, given that we know the class label.

Let's break down how this works in practice:

Calculate Prior Probabilities: The algorithm first calculates the prior probability of each class. This is the probability of a data point belonging to a particular class before considering its features. For example, in a spam detection scenario, the probability of an email being spam might be 0.2 (20%), while the probability of it being not spam is 0.8 (80%).Calculate Likelihoods: Next, the algorithm calculates the likelihood of observing each feature given each class. This involves determining the probability of seeing a particular feature value given that the data point belongs to a specific class. For instance, what's the likelihood of seeing the word "free" in an email given that it's spam? What's the likelihood of seeing the word "meeting" given that it's not spam?Apply Bayes' Theorem: For a new data point, the algorithm combines the prior probabilities and likelihoods using Bayes' theorem to calculate the posterior probability of the data point belonging to each class. The posterior probability is the updated probability of an event (in this case, the data point belonging to a certain class) after considering new information (the observed features). This represents the revised belief about the class label after considering the observed features.Predict the Class: Finally, the algorithm assigns the data point to the class with the highest posterior probability.While this assumption of feature independence is often violated in real-world data (words like "free" and "viagra" might indeed co-occur more often in spam), Naive Bayes often performs surprisingly well in practice.

The specific implementation of Naive Bayes depends on the type of features and their assumed distribution:

Gaussian Naive Bayes: This is used when the features are continuous and assumed to follow a Gaussian distribution (a bell curve). For example, if predicting whether a customer will purchase a product based on their age and income, Gaussian Naive Bayes could be used, assuming age and income are normally distributed.Multinomial Naive Bayes: This is suitable for discrete features and is often used in text classification. For instance, in spam filtering, the frequency of words like "free" or "money" might be the features, and Multinomial Naive Bayes would model the probability of these words appearing in spam and non-spam emails.Bernoulli Naive Bayes: This type is employed for binary features, where the feature is either present or absent. In document classification, a feature could be whether a specific word is present in the document. Bernoulli Naive Bayes would model the probability of this presence or absence for each class.The choice of which type of Naive Bayes to use depends on the nature of the data and the specific problem being addressed.

While Naive Bayes is relatively robust, it's helpful to be aware of some data assumptions:

Feature Independence: As discussed, the core assumption is that features are conditionally independent given the class.Data Distribution: The choice of Naive Bayes classifier (Gaussian, Multinomial, Bernoulli) depends on the assumed distribution of the features.Sufficient Training Data: Although Naive Bayes can work with limited data, it is important to have sufficient data to estimate probabilities accurately.

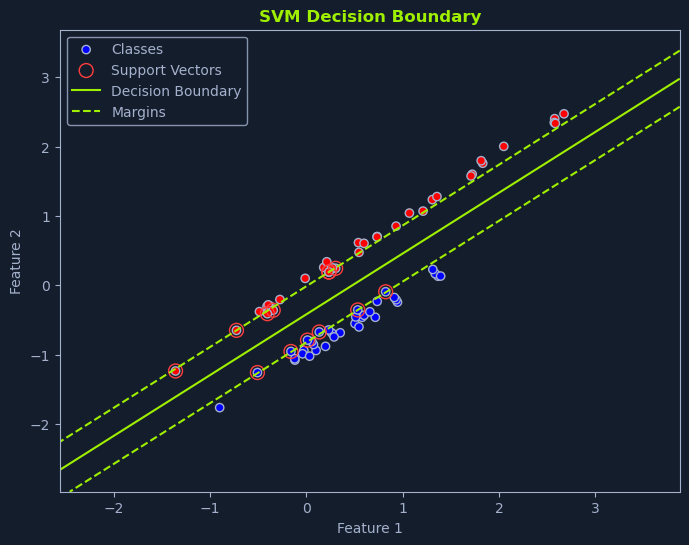

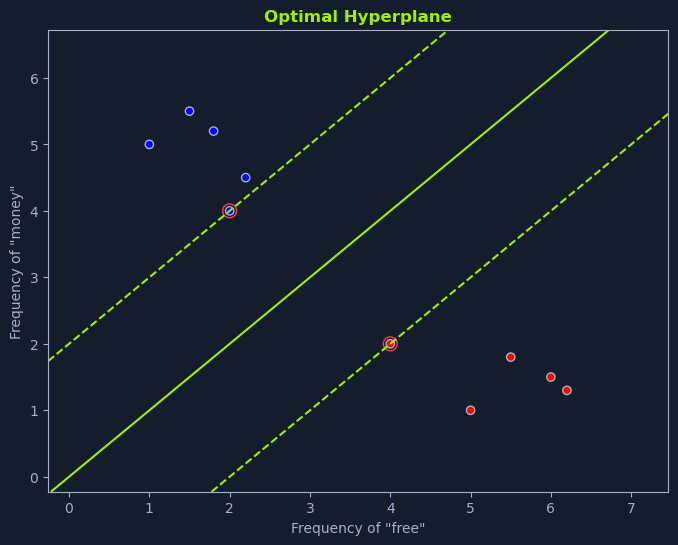

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are powerful supervised learning algorithms for classification and regression tasks. They are particularly effective in handling high-dimensional data and complex non-linear relationships between features and the target variable. SVMs aim to find the optimal hyperplane that maximally separates different classes or fits the data for regression.

An SVM aims to find the hyperplane that maximizes the margin. The margin is the distance between the hyperplane and the nearest data points of each class. These nearest data points are called support vectors and are crucial in defining the hyperplane and the margin.

By maximizing the margin, SVMs aim to find a robust decision boundary that generalizes well to new, unseen data. A larger margin provides more separation between the classes, reducing the risk of misclassification.

A linear SVM is used when the data is linearly separable, meaning a straight line or hyperplane can perfectly separate the classes. The goal is to find the optimal hyperplane that maximizes the margin while correctly classifying all the training data points.

Imagine you're tasked with classifying emails as spam or not spam based on the frequency of the words "free" and "money." If we plot each email on a graph where the x-axis represents the frequency of "free" and the y-axis represents the frequency of "money," we can visualize how SVMs work.

The optimal hyperplane is the one that maximizes the margin between the closest data points of different classes. This margin is called the separating hyperplane. The data points closest to the hyperplane are called support vectors, as they "support" or define the hyperplane and the margin.

Maximizing the margin is intended to create a robust classifier. A larger margin allows the SVM to tolerate some noise or variability in the data without misclassifying points. It also improves the model's generalization ability, making it more likely to perform well on unseen data.

In the spam classification scenario depicted in the graph, the linear SVM identifies the line that maximizes the distance between the nearest spam and non-spam emails. This line serves as the decision boundary for classifying new emails. Emails falling on one side of the line are classified as spam, while those on the other side are classified as not spam.

The hyperplane is defined by an equation of the form:

Code: python

w * x + b = 0

Where:

w is the weight vector, perpendicular to the hyperplane.x is the input feature vector.b is the bias term, which shifts the hyperplane relative to the origin.The SVM algorithm learns the optimal values for w and b during the training process.

In many real-world scenarios, data is not linearly separable. This means we cannot draw a straight line or hyperplane to perfectly separate the different classes. In these cases, non-linear SVMs come to the rescue.

Non-linear SVMs utilize a technique called the kernel trick. This involves using a kernel function to map the original data points into a higher-dimensional space where they become linearly separable.

Imagine separating a mixture of red and blue marbles on a table. If the marbles are mixed in a complex pattern, you might be unable to draw a straight line to separate them. However, if you could lift some marbles off the table (into a higher dimension), you might be able to find a plane that separates them.

This is essentially what a kernel function does. It transforms the data into a higher-dimensional space where a linear hyperplane can be found. This hyperplane corresponds to a non-linear decision boundary when mapped back to the original space.

Several kernel functions are commonly used in non-linear SVMs:

Polynomial Kernel: This kernel introduces polynomial terms (like x², x³, etc.) to capture non-linear relationships between features. It's like adding curves to the decision boundary.Radial Basis Function (RBF) Kernel: This kernel uses a Gaussian function to map data points to a higher-dimensional space. It's one of the most popular and versatile kernel functions, capable of capturing complex non-linear patterns.Sigmoid Kernel: This kernel is similar to the sigmoid function used in logistic regression. It introduces non-linearity by mapping the data points to a space with a sigmoid-shaped decision boundary.The kernel function choice depends on the data's nature and the model's desired complexity.

Non-linear SVMs are particularly useful in applications like image classification. Images often have complex patterns that linear boundaries cannot separate.

For instance, imagine classifying images of cats and dogs. The features might be things like fur texture, ear shape, and facial features. These features often have non-linear relationships. A non-linear SVM with an appropriate kernel function can capture these relationships and effectively separate cat images from dog images.

Finding this optimal hyperplane involves solving an optimization problem. The problem can be formulated as:

Code: python

Minimize: 1/2 ||w||^2

Subject to: yi(w * xi + b) >= 1 for all i

Where:

w is the weight vector that defines the hyperplanexi is the feature vector for data point iyi is the class label for data point i (-1 or 1)b is the bias termThis formulation aims to minimize the magnitude of the weight vector (which maximizes the margin) while ensuring that all data points are correctly classified with a margin of at least 1.

SVMs have few assumptions about the data:

No Distributional Assumptions: SVMs do not make strong assumptions about the underlying distribution of the data.Handles High Dimensionality: They are effective in high-dimensional spaces, where the number of features is larger than the number of data points.Robust to Outliers: SVMs are relatively robust to outliers, focusing on maximizing the margin rather than fitting all data points perfectly.SVMs are powerful and versatile algorithms that have proven effective in various machine-learning tasks. Their ability to handle high-dimensional data and complex non-linear relationships makes them a valuable tool for solving challenging classification and regression problems.

Unsupervised learning algorithms explore unlabeled data, where the goal is not to predict a specific outcome but to discover hidden patterns, structures, and relationships within the data. Unlike supervised learning, where the algorithm learns from labeled examples, unsupervised learning operates without the guidance of predefined labels or "correct answers."

Think of it as exploring a new city without a map. You observe the surroundings, identify landmarks, and notice how different areas are connected. Similarly, unsupervised learning algorithms analyze the inherent characteristics of the data to uncover hidden structures and patterns.

Unsupervised learning algorithms identify similarities, differences, and patterns in the data. They can group similar data points together, reduce the number of variables while preserving essential information, or identify unusual data points that deviate from the norm.

These algorithms are valuable for tasks where labeled data is scarce, expensive, or unavailable. They enable us to gain insights into the data's underlying structure and organization, even without knowing the specific outcomes or labels.

Unsupervised learning problems can be broadly categorized into:

Clustering: Grouping similar data points together based on their characteristics. This is like organizing a collection of books by genre or grouping customers based on their purchasing behavior.Dimensionality Reduction: Reducing the number of variables (features) in the data while preserving essential information. This is analogous to summarizing a long document into a concise abstract or compressing an image without losing its important details.Anomaly Detection: Identifying unusual data points that deviate significantly from the norm. This is like spotting a counterfeit bill among a stack of genuine ones or detecting fraudulent credit card transactions.To effectively understand unsupervised learning, it's crucial to grasp some core concepts.

The cornerstone of unsupervised learning is unlabeled data. Unlike supervised learning, where data points come with corresponding labels or target variables, unlabeled data lacks these predefined outcomes. The algorithm must rely solely on the data's inherent characteristics and input features to discover patterns and relationships.

Think of it as analyzing a collection of photographs without any captions or descriptions. Even without knowing the specific context of each photo, you can still group similar photos based on visual features like color, composition, and subject matter.

Many unsupervised learning algorithms rely on quantifying the similarity or dissimilarity between data points. Similarity measures calculate how alike or different two data points are based on their features. Common measures include:

Euclidean Distance: Measures the straight-line distance between two points in a multi-dimensional space.Cosine Similarity: Measures the angle between two vectors, representing data points, with higher values indicating greater similarity.Manhattan Distance: Calculates the distance between two points by summing the absolute differences of their coordinates.The choice of similarity measure depends on the nature of the data and the specific algorithm being used.

Clustering tendency refers to the data's inherent propensity to form clusters or groups. Before applying clustering algorithms, assessing whether the data exhibits a natural tendency to form clusters is essential. If the data is uniformly distributed without inherent groupings, clustering algorithms might not yield meaningful results.

Evaluating the quality and meaningfulness of the clusters produced by a clustering algorithm is crucial. Cluster validity involves assessing metrics like:

Cohesion: Measures how similar data points are within a cluster. Higher cohesion indicates a more compact and well-defined cluster.Separation: Measures how different clusters are from each other. Higher separation indicates more distinct and well-separated clusters.Various cluster validity indices, such as the silhouette score and Davies-Bouldin index, quantify these aspects and help determine the optimal number of clusters.

Dimensionality refers to the number of features or variables in the data. High dimensionality can pose challenges for some unsupervised learning algorithms, increasing computational complexity and potentially leading to the "curse of dimensionality," where data becomes sparse and distances between points become less meaningful.

The intrinsic dimensionality of data represents its inherent or underlying dimensionality, which may be lower than the actual number of features. It captures the essential information contained in the data. Dimensionality reduction techniques aim to reduce the number of features while preserving this intrinsic dimensionality.

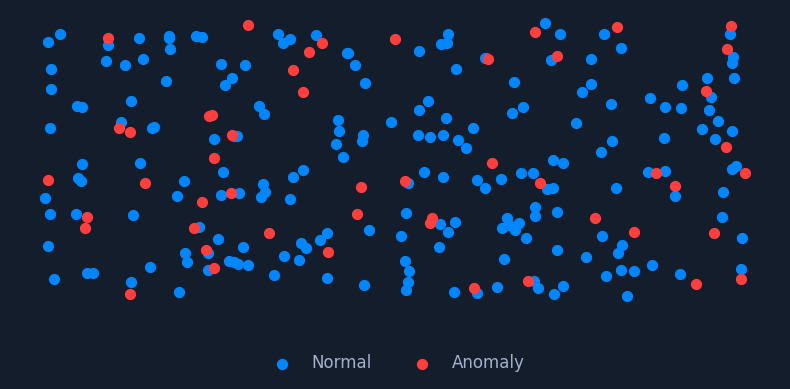

An anomaly is a data point that deviates significantly from the norm or expected pattern in the data. Anomalies can represent unusual events, errors, or fraudulent activities. Detecting anomalies is crucial in various applications, such as fraud detection, network security, and system monitoring.

An outlier is a data point that is far away from the majority of other data points. While similar to an anomaly, the term "outlier" is often used in a broader sense. Outliers can indicate errors in data collection, unusual observations, or potentially interesting patterns.

Feature scaling is essential in unsupervised learning to ensure that all features contribute equally to the distance calculations and other computations. Common techniques include:

Min-Max Scaling: Scales features to a fixed range.Standardization (Z-score normalization): Transforms features to have zero mean and unit variance.

K-means clustering is a popular unsupervised learning algorithm for partitioning a dataset into K distinct, non-overlapping clusters. The goal is to group similar data points, where similarity is typically measured by the distance between data points in a multi-dimensional space.

Imagine you have a dataset of customers with information about their purchase history, demographics, and browsing activity. K-means clustering can group these customers into distinct segments based on their similarities. This can be valuable for targeted marketing, personalized recommendations, and customer relationship management.

K-means is an iterative algorithm that aims to minimize the variance within each cluster. This means it tries to group data points so that the points within a cluster are as close to each other and as far from data points in other clusters as possible.

The algorithm follows these steps:

Initialization: Randomly select K data points from the dataset as the initial cluster centers (centroids). These centroids represent the average point within each cluster.Assignment: Assign each data point to the nearest cluster center based on a distance metric, such as Euclidean distance.Update: Recalculate the cluster centers by taking the mean of all data points assigned to each cluster. This updates the centroid to represent the center of the cluster better.Iteration: Repeat steps 2 and 3 until the cluster centers no longer change significantly or a maximum number of iterations is reached. This iterative process refines the clusters until they stabilize.Euclidean distance is a common distance metric used to measure the similarity between data points in K-means clustering. It calculates the straight-line distance between two points in a multi-dimensional space.

For two data points x and y with n features, the Euclidean distance is calculated as:

Code: python

d(x, y) = sqrt(Σ (xi - yi)^2)

Where:

xi and yi are the values of the i-th feature for data points x and y, respectively.Determining the optimal number of clusters (K) is crucial in K-means clustering. The choice of K significantly impacts the clustering results and their interpretability. Selecting too few clusters can lead to overly broad groupings, while selecting too many can result in overly granular and potentially meaningless clusters.

Unfortunately, there is no one-size-fits-all method for determining the optimal K. It often involves a combination of techniques and domain expertise.

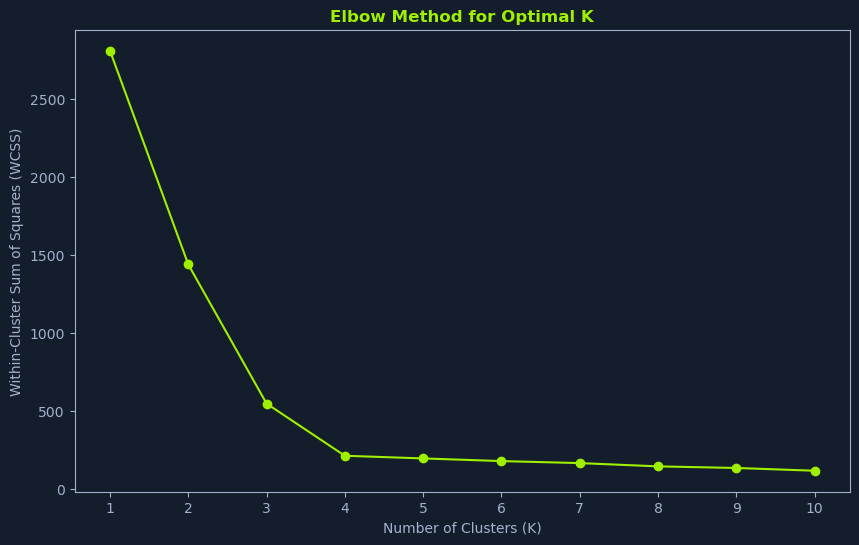

The Elbow Method is a graphical technique that helps estimate the optimal K by visualizing the relationship between the number of clusters and the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS).

It follows the following steps:

Run K-means for a range of K values: Perform K-means clustering for different values of K, typically starting from 1 and increasing incrementally.Calculate WCSS: For each value of K, calculate the WCSS. The WCSS measures the total variance within each cluster. Lower WCSS values indicate that the data points within clusters are more similar.Plot WCSS vs. K: Plot the WCSS values against the corresponding K values.Identify the Elbow Point: Look for the "elbow" point in the plot. This is where the WCSS starts to decrease at a slower rate. This point often suggests a good value for K, indicating a balance between minimizing within-cluster variance and avoiding excessive granularity.The elbow point represents a trade-off between model complexity and model fit. Increasing K beyond the elbow point might lead to overfitting, where the model captures noise in the data rather than meaningful patterns.

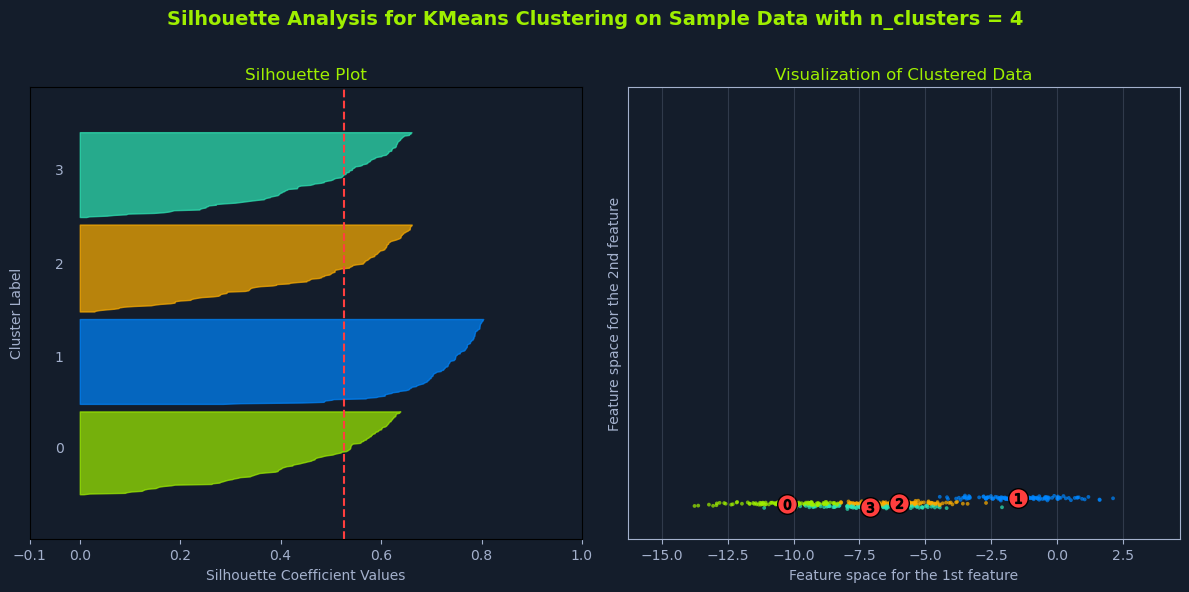

Silhouette analysis provides a more quantitative approach to evaluating different values of K. It measures how similar a data point is to its own cluster compared to others.

The process is broken down into four core steps:

Run K-means for a range of K values: Similar to the elbow method, perform K-means clustering for different values of K.Calculate Silhouette Scores: For each data point, calculate its silhouette score. The silhouette score ranges from -1 to 1, where:Calculate Average Silhouette Score: For each value of K, calculate the average silhouette score across all data points.Choose K with the Highest Score: Select the value of K that yields the highest average silhouette score. This indicates the clustering solution with the best-defined clusters.Higher silhouette scores generally indicate better-defined clusters, where data points are more similar to their cluster and less similar to others.

While the elbow method and silhouette analysis provide valuable guidance, domain expertise is often crucial in choosing the optimal K. Consider the problem's specific context and the desired level of granularity in the clusters.

In some cases, practical considerations might outweigh purely quantitative measures. For instance, if the goal is to segment customers for targeted marketing, you might choose a K that aligns with the number of distinct marketing campaigns you can realistically manage.

Other factors to consider include:

Computational Cost: Higher values of K generally require more computational resources.Interpretability: The resulting clusters should be meaningful and interpretable in the context of the problem.By combining these techniques and considering the task's specific requirements, you can effectively choose an optimal K for K-means clustering that yields meaningful and insightful results.

K-means clustering makes certain assumptions about the data:

Cluster Shape: It assumes that clusters are spherical and have similar sizes. This means it might not perform well if the clusters have complex shapes or vary significantly in size.Feature Scale: It is sensitive to the scale of the features. Features with larger scales can have a greater influence on the clustering results. Therefore, it's important to standardize or normalize the data before applying K-means.Outliers: K-means can be sensitive to outliers, data points that deviate significantly from the norm. Outliers can distort the cluster centers and affect the clustering results.

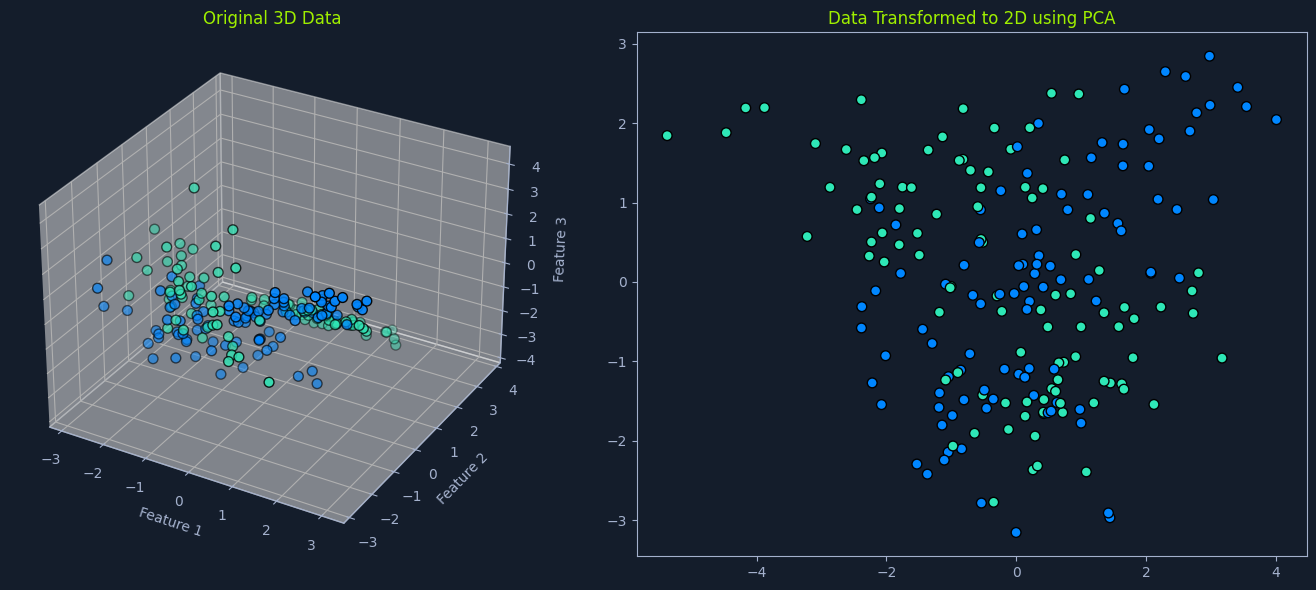

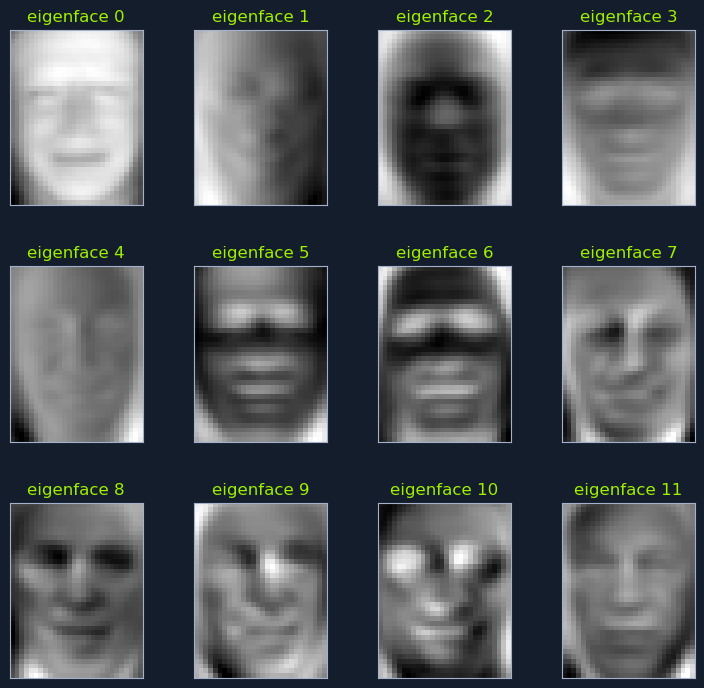

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a dimensionality reduction technique that transforms high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional representation while preserving as much original information as possible. It achieves this by identifying the principal components and new variables that are linear combinations of the original features and capturing the maximum variance in the data. PCA is widely used for feature extraction, data visualization, and noise reduction.

For example, in image processing, PCA can reduce the dimensionality of image data by identifying the principal components that capture the most important features of the images, such as edges, textures, and shapes.

Think of it as finding the most important "directions" in the data. Imagine a scatter plot of data points. PCA finds the lines that best capture the spread of the data. These lines represent the principal components.

Consider a database of facial images. PCA can be used to identify the principal components that capture the most significant variations in facial features, such as eye shape, nose size, and mouth width. By projecting the facial images onto a lower-dimensional space defined by these principal components, we can efficiently search for similar faces.

There are three key concepts to PCA:

Variance: Variance measures the spread or dispersion of data points around the mean. PCA aims to find principal components that maximize variance, capturing the most significant information in the data.Covariance: Covariance measures the relationship between two variables. PCA considers the covariance between different features to identify the directions of maximum variance.Eigenvectors and Eigenvalues: Eigenvectors represent the directions of the principal components, and eigenvalues represent the amount of variance explained by each principal component.The PCA algorithm follows these steps:

Standardize the data: Subtract the mean and divide by the standard deviation for each feature to ensure that all features have the same scale.Calculate the covariance matrix: Compute the covariance matrix of the standardized data, which represents the relationships between different features.Compute the eigenvectors and eigenvalues: Determine the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the covariance matrix. The eigenvectors represent the directions of the principal components, and the eigenvalues represent the amount of variance explained by each principal component.Sort the eigenvectors: Sort the eigenvectors in descending order of their corresponding eigenvalues. The eigenvectors with the highest eigenvalues capture the most variance in the data.Select the principal components: Choose the top k eigenvectors, where k is the desired number of dimensions in the reduced representation.Transform the data: Project the original data onto the selected principal components to obtain the lower-dimensional representation.By following these steps, PCA can effectively reduce the dimensionality of a dataset while retaining the most important information.

Before diving into the eigenvalue equation, it's important to understand what eigenvectors and eigenvalues are and their significance in linear algebra and machine learning.

An eigenvector is a special vector that remains in the same direction when a linear transformation (such as multiplication by a matrix) is applied to it. Mathematically, if A is a square matrix and v is a non-zero vector, then v is an eigenvector of A if:

Code: python

A * v = λ * v

Here, λ (lambda) is the eigenvalue associated with the eigenvector v.

The eigenvalue λ represents the scalar factor by which the eigenvector v is scaled during the linear transformation. In other words, when you multiply the matrix A by its eigenvector v, the result is a vector that points in the same direction as v but stretches or shrinks by a factor of λ.

Consider a rubber band stretched along a coordinate system. A vector can represent the rubber band, and we can transform it using a matrix.

Let's say the rubber band is initially aligned with the x-axis and has a length of 1 unit. This can be represented by the vector v = [1, 0].

Now, imagine applying a linear transformation (stretching it) represented by the matrix A:

Code: python

A = [[2, 0],

[0, 1]]

When we multiply the matrix A by the vector v, we get:

Code: python

A * v = [[2, 0],

[0, 1]] * [1, 0] = [2, 0]

The resulting vector is [2, 0], which points in the same direction as the original vector v but has been stretched by a factor of 2. The eigenvector is v = [1, 0], and the corresponding eigenvalue is λ = 2.

In Principal Component Analysis (PCA), the eigenvalue equation helps identify the principal components of the data. The principal components are obtained by solving the following eigenvalue equation:

Code: python

C * v = λ * v

Where:

C is the standardized data's covariance matrix. This matrix represents the relationships between different features, with each element indicating the covariance between two features.v is the eigenvector. Eigenvectors represent the directions of the principal components in the feature space, indicating the directions of maximum variance in the data.λ is the eigenvalue. Eigenvalues represent the amount of variance explained by each corresponding eigenvector (principal component). Larger eigenvalues correspond to eigenvectors that capture more variance.Solving this equation involves finding the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the covariance matrix. This can be done using techniques like:

Eigenvalue Decomposition: Directly computing the eigenvalues and eigenvectors.Singular Value Decomposition (SVD): A more numerically stable method that decomposes the data matrix into singular vectors and singular values related to the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the covariance matrix.Once the eigenvectors and eigenvalues are found, they are sorted in descending order of their corresponding eigenvalues. The top k eigenvectors (those with the largest eigenvalues) are selected to form the new feature space. These top k eigenvectors represent the principal components that capture the most significant variance in the data.

The transformation of the original data X into the lower-dimensional representation Y can be expressed as:

Code: python

Y = X * V

Where:

Y is the transformed data matrix in the lower-dimensional space.X is the original data matrix.V is the matrix of selected eigenvectors.This transformation projects the original data points onto the new feature space defined by the principal components, resulting in a lower-dimensional representation that captures the most significant variance in the data. This reduced representation can be used for various purposes such as visualization, noise reduction, and improving the performance of machine learning models.

The number of principal components to retain is a crucial decision in PCA. It determines the trade-off between dimensionality reduction and information preservation.

A common approach is to plot the explained variance ratio against the number of components. The explained variance ratio indicates the proportion of total variance captured by each principal component. By examining the plot, you can choose the number of components that capture a sufficiently high percentage of the total variance (e.g., 95%). This ensures that the reduced representation retains most of the essential information from the original data.

PCA makes certain assumptions about the data:

Linearity: It assumes that the relationships between features are linear.Correlation: It works best when there is a significant correlation between features.Scale: It is sensitive to the scale of the features, so it is important to standardize the data before applying PCA.PCA is a powerful technique for dimensionality reduction and data analysis. It can simplify complex datasets, extract meaningful features, and visualize data in a lower-dimensional space. However, knowing its assumptions and limitations is important to ensure its effective and appropriate application.

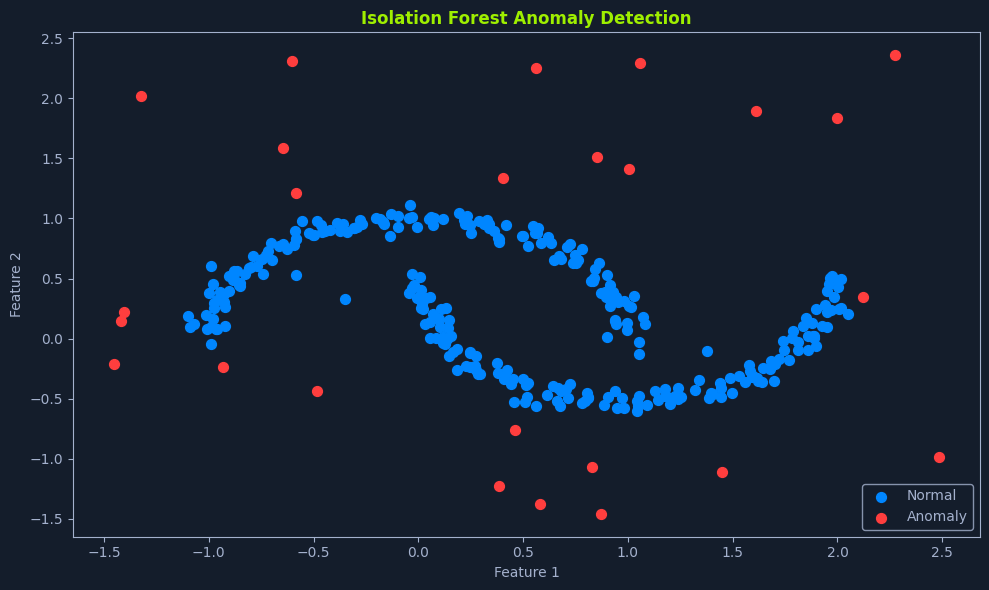

Anomaly detection, also known as outlier detection, is crucial in unsupervised learning. It identifies data points that deviate significantly from normal behavior within a dataset. These anomalous data points, often called outliers, can indicate critical events, such as fraudulent activities, system failures, or medical emergencies.

Think of it like a security system that monitors a building. The system learns the normal activity patterns, such as people entering and exiting during business hours. It raises an alarm if it detects something unusual, like someone trying to break in at night. Similarly, anomaly detection algorithms learn the normal patterns in data and flag any deviations as potential anomalies.

Anomalies can be broadly categorized into three types:

Point Anomalies: Individual data points significantly differ from the rest—for example, a sudden spike in network traffic or an unusually high credit card transaction amount.Contextual Anomalies: Data points considered anomalous within a specific context but not necessarily in isolation. For example, a temperature reading of 30°C might be expected in summer but anomalous in winter.Collective Anomalies: A group of data points that collectively deviate from the normal behavior, even though individual data points might not be considered anomalous. For example, a sudden surge in login attempts from multiple unknown IP addresses could indicate a coordinated attack.Various techniques are employed for anomaly detection, including: