In this digital age, understanding potential vulnerabilities and their mitigation is paramount. However, these vulnerabilities are not purely software-based. Significant threats exist that a simple software update cannot resolve. Hardware security requires serious consideration, extending from specific technologies like Bluetooth to the microchips powering our digital age.

This mini-module provides a theoretical focus on Bluetooth hacking methods, cryptanalysis side-channel attacks, and microprocessor vulnerabilities.

Bluetooth technology, designed for short-range wireless communication between devices, is ubiquitous in today's digital era. Despite its convenience, it opens up a new attack surface for hackers. In this section, we'll dive into several types of Bluetooth hacking:

Bluesnarfing: A cyber-attack involving unauthorised access to information from wireless devices through Bluetooth.Bluejacking: An attack that sends unsolicited messages to Bluetooth-enabled devices.BlueSmacking: A Denial-of-Service attack that overwhelms a device's Bluetooth connection.Bluebugging: A technique used to gain control over a device via Bluetooth.BlueBorne: A set of vulnerabilities that allow attackers to take control of devices, spread malware, or perform other malicious activities via Bluetooth.KNOB (Key Negotiation of Bluetooth): An attack that manipulates the data encryption process during Bluetooth connection establishment, weakening security.BIAS (Bluetooth Impersonation AttackS): This attack exploits a vulnerability in the pairing process, allowing an attacker to impersonate a trusted device.Cryptanalysis side-channel attacks are an intriguing topic in cybersecurity. These attacks utilise information gained from implementing and running a computer system rather than brute force or theoretical weaknesses in algorithms. We'll discuss:

Timing Attacks: These exploit the correlation between the computation time of cryptographic algorithms and the secrets they process.Power-Monitoring Attacks: These monitor the power consumption of a device to determine what data it is processing.Microprocessors form the backbone of any computational device. However, their complex design and optimisation strategies often introduce vulnerabilities. We'll explore what microprocessors are, and two notorious microprocessor vulnerabilities:

Spectre and MeltdownAs well as delve into mitigation strategies such as:

Retpoline: A binary modification technique used to thwart branch target injection.Kernel Page Table Isolation (KPTI): A technique used to isolate the kernel's memory space from user space processes.Bluetooth, a wireless technology standard, is designed for transferring data over short distances from fixed and mobile devices. The technology operates by establishing personal area networks (PANs) using radio frequencies in the ISM band from 2.402 GHz to 2.480 GHz. Conceived as a wireless alternative to RS-232 data cables, Bluetooth has been widely adopted due to its flexibility and ease of use. The name Bluetooth is derived from the epithet of a tenth-century king, Harald Bluetooth, who unified Denmark and Norway. The technology's use span numerous devices, such as smartphones, laptops, audio devices, and many IoT devices, with annual device shipments expected to exceed 7 billion by 2026, according to the Bluetooth 2022 Market Update.

Bluetooth functionality is based on several key concepts, including device pairing, piconets, and data transfer protocols. The first step in establishing a Bluetooth connection is the pairing process. This involves two devices discovering each other and establishing a connection:

Discovery: One device makes itself discoverable, broadcasting its presence to other Bluetooth devices within range.Pairing Request: A second device finds the discoverable device and sends a pairing request.Authentication: The devices authenticate each other through a process involving a shared secret, known as a link key or long-term key. This may involve entering a PIN on one or both devices.Once the devices are paired, they remember each other's details and can automatically connect in the future without needing to go through the pairing process again.

After pairing, Bluetooth devices form a network known as a piconet. This collection of devices connected via Bluetooth technology consists of one main device and up to seven active client devices. The main device coordinates communication within the piconet.

Multiple piconets can interact to form a larger network known as a scatternet. In this configuration, some devices serve as bridges, participating in multiple piconets and thus enabling inter-piconet communication.

Bluetooth connections facilitate both data and audio communication, with data transfer occurring via packets. The primary device in the piconet dictates the schedule for packet transmission. The Bluetooth specification identifies two types of links for data transfer:

Synchronous Connection-Oriented (SCO) links: Primarily used for audio communication, these links reserve slots at regular intervals for data transmission, guaranteeing steady, uninterrupted communication ideal for audio data.Asynchronous Connection-Less (ACL) links: These links cater to transmitting all other types of data. Unlike SCO links, ACL links do not reserve slots but transmit data whenever bandwidth allows.As the utilisation of Bluetooth expands, so does the need for a comprehensive understanding of the associated security risks. The convenience of Bluetooth technology has inadvertently opened a new avenue for potential attacks that could compromise personal and organisational security.

In Bluetooth technology, risk can be defined as any potential event that exploits the Bluetooth connection to compromise data or systems' confidentiality, integrity, or availability. Bluetooth risks often emanate from the wireless nature of the technology that allows for remote, unauthorised access to a device, thereby presenting opportunities for nefarious activities such as eavesdropping, data theft, or malicious control of a device.

The array of risks associated with Bluetooth can be broadly classified into several categories:

Unauthorised Access: This risk involves unauthorised entities gaining unsolicited access to Bluetooth-enabled devices. Attackers can exploit vulnerabilities to take control of the device or eavesdrop on data exchanges, potentially compromising sensitive information and user privacy.Data Theft: Bluetooth-enabled devices store and transmit vast amounts of personal and sensitive data. The risk of data theft arises when attackers exploit vulnerabilities to extract this data without authorisation. Stolen information may include contact lists, messages, passwords, financial details, or other confidential data.Interference: Bluetooth operates on the 2.4 GHz band, which is shared by numerous other devices and technologies. This creates a risk of interference, where malicious actors may disrupt or corrupt Bluetooth communication. Intentional interference can lead to data loss, connection instability, or other disruptions in device functionality.Denial of Service (DoS): Attackers can launch Denial of Service attacks on Bluetooth-enabled devices by overwhelming them with an excessive volume of requests or by exploiting vulnerabilities in Bluetooth protocols. This can result in the targeted device becoming unresponsive, rendering it unable to perform its intended functions.Device Tracking: Bluetooth technology relies on radio signals to establish connections between devices. Attackers can exploit this characteristic to track the physical location of Bluetooth-enabled devices. Such tracking compromises the privacy and security of device owners, potentially leading to stalking or other malicious activities.Over the years, several classifications of Bluetooth attacks have been identified, each with its unique characteristics and potential risks. Understanding these attack types is essential for promoting awareness and implementing effective security measures. The following table provides a comprehensive overview of various Bluetooth attacks and their descriptions:

| Bluetooth Attack | Description |

|---|---|

| Bluejacking | Bluejacking is a relatively harmless type of Bluetooth hacking where an attacker sends unsolicited messages or business cards to a device. Although it doesn't pose a direct threat, it can infringe on privacy and be a nuisance to the device owner. |

| Bluesnarfing | Bluesnarfing entails unauthorised access to a Bluetooth-enabled device's data, such as contacts, messages, or calendar entries. Attackers exploit vulnerabilities to retrieve sensitive information without the device owner's knowledge or consent. This could lead to privacy violations and potential misuse of personal data. |

| Bluebugging | Bluebugging enables an attacker to control a Bluetooth device, including making calls, sending messages, and accessing data. By exploiting security weaknesses, attackers can gain unauthorised access and manipulate the device's functionalities, posing a significant risk to user privacy and device security. |

| Car Whisperer | Car Whisperer is a Bluetooth hack that specifically targets vehicles. Attackers exploit Bluetooth vulnerabilities to remotely unlock car doors or even start the engine without physical access. This poses a serious security threat as it can lead to car theft and compromise the safety of vehicle owners. |

| Bluesmacking & Denial of Service | Denial of Service (DoS) attacks leverage vulnerabilities in Bluetooth protocols to disrupt or disable the connection between devices. Bluesmacking, a specific type of DoS attack, involves sending excessive Bluetooth connection requests, overwhelming the target device and rendering it unusable. These attacks can disrupt normal device operations and cause inconvenience to users. |

| Man-in-the-Middle | Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks intercept and manipulate data exchanged between Bluetooth devices. By positioning themselves between the communicating devices, attackers can eavesdrop on sensitive information or alter the transmitted data. MitM attacks compromise the confidentiality and integrity of Bluetooth communications, posing a significant risk to data security. |

| BlueBorne | Discovered in 2017, BlueBorne is a critical Bluetooth vulnerability that allows an attacker to take control of a device without requiring any user interaction or device pairing. Exploiting multiple zero-day vulnerabilities, BlueBorne presents a severe threat to device security and user privacy. Its pervasive nature makes it a significant concern across numerous Bluetooth-enabled devices. |

| Key Extraction | Key extraction attacks aim to retrieve encryption keys used in Bluetooth connections. By obtaining these keys, attackers can decrypt and access sensitive data transmitted between devices. Key extraction attacks undermine the confidentiality of Bluetooth communications and can result in exposure of sensitive information. |

| Eavesdropping | Eavesdropping attacks involve intercepting and listening to Bluetooth communications. Attackers capture and analyse data transmitted between devices, potentially gaining sensitive information such as passwords, financial details, or personal conversations. Eavesdropping attacks compromise the confidentiality of Bluetooth communications and can lead to severe privacy violations. |

| Bluetooth Impersonation Attack | In this attack type, an attacker impersonates a trusted Bluetooth device to gain unauthorised access or deceive the user. By exploiting security vulnerabilities, attackers can trick users into connecting to a malicious device, resulting in data theft, unauthorised access, or other malicious activities. Bluetooth impersonation attacks undermine trust and integrity in Bluetooth connections, posing a significant risk to device security and user trust. |

Considering the age of Bluetooth, many of the better-known and frequently cited Bluetooth attacks and vulnerabilities were discovered in the early to mid-2000s.

Bluejacking refers to a legacy attack involving sending unsolicited messages to Bluetooth-enabled devices. Unlike Bluesnarfing, Bluejacking does not involve accessing or stealing data from the targeted device. Instead, it uses the Bluetooth "business card" feature to send anonymous messages, typically in text or images. As such, it is often seen as a prank or nuisance rather than a serious security threat.

In a typical bluejacking scenario, the attacker starts by scanning for other nearby Bluetooth devices. The attacker then chooses a target from the discovered devices and proceeds to craft a text message or selects an image. Using the Object Push Profile (OPP), they send unsolicited messages or images to the targeted device.

The Object Push Profile (OPP) is a standard Bluetooth profile that facilitates the basic exchange of objects or files between devices. These objects can range from Virtual Business Cards (vCards), calendar entries (vCalendars), notes, or other forms of data encapsulated in a file.

Notably, this entire process can be accomplished without establishing a paired connection with the target device, making bluejacking a stealthy operation that leaves little trace other than an unexpected message on the recipient's device.

The impact of Bluejacking is generally limited to annoyance or inconvenience; however, in some instances, Bluejacking can be used maliciously. For example, it could be used as part of a social engineering attack, where the unsolicited message is designed to trick the recipient into revealing sensitive information or performing an action that compromises their security, such as installing malware onto their device.

Over time, the awareness about bluejacking spread, and manufacturers and developers began implementing security measures to address the vulnerability, such as changing default settings. These improvements made it significantly more difficult for unauthorised individuals to perform bluejacking.

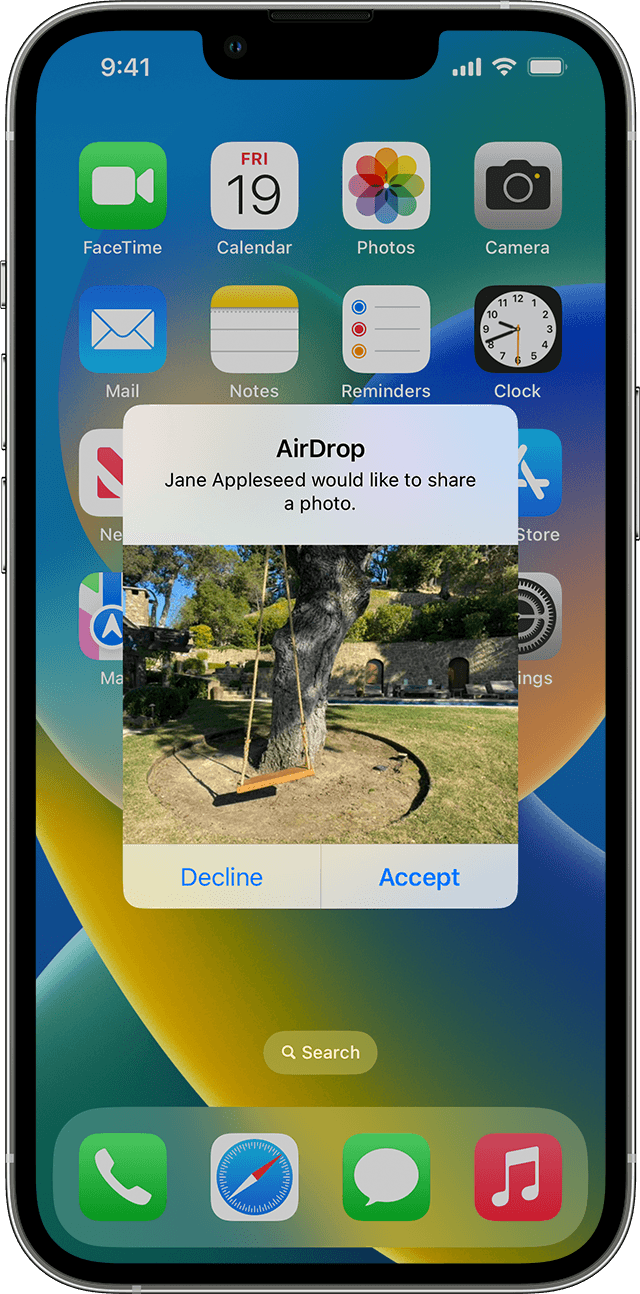

Apple devices were susceptible to an attack very similar to Bluejacking via AirDrop. AirDrop is a proprietary service Apple provides that allows users to transfer files among supported Macintosh computers and iOS devices over Wi-Fi and Bluetooth—without using mail or a mass storage device.

AirDrop utilises Bluetooth to create a peer-to-peer network between devices. To share a file via AirDrop, the user selects the Share button on the document, photo, or webpage they wish to send, chooses AirDrop, and selects the device within the range they want to share with. When a file is received via AirDrop, it appears as a notification, allowing the user to either accept or decline. If the incoming AirDrop item is accepted, it is automatically saved into the user's Photos, Downloads, or Files folder on their device.

However, this feature has been exploited for spamming purposes.

If your AirDrop was set up to receive files from Everyone, this means that anyone within AirDrop range—roughly 30 feet (9 meters)—could share files with you.

In crowded areas such as concerts, subway trains, or aeroplanes, malicious users could send unsolicited photos or other files to any device set to receive from Everyone. The sending of unsolicited files is often termed AirDrop spamming or cyber flashing. However, Apple modified these settings in iOS 16.2, where the Everyone option had to be explicitly enabled before it automatically disabled itself after 10 minutes, thus only allowing your contacts to send you unsolicited files.

Bluesnarfing is a legacy attack that provides unauthorised access to a Bluetooth-enabled device to extract information, whose origins can be traced back to around 2003. The term derives from 'snarfing,' a colloquial term in computer security, which denotes unauthorised data acquisition, and the 'blue' prefix refers to Bluetooth as the method of access. Thus, Bluesnarfing is essentially a data theft method exploiting Bluetooth connectivity.

Bluesnarfing entails several steps. The process begins with the attacker identifying an active, vulnerable Bluetooth device within range. Subsequently, the attacker exploits a vulnerability in the device's Bluetooth implementation, allowing unauthorised access. Once access is obtained, the attacker can extract information from the device, such as contact information, calendars, emails, text messages, and even media files. Notably, the attack can be perpetrated without alerting the device's owner, making it a surreptitious exploit.

The potential impact of Bluesnarfing is significant, given the nature of data that can be extracted. Personal information, including contact details and media files such as photos and videos, could potentially be used for identity theft or blackmail. Additionally, business-related information, such as meeting details or confidential emails, could be used for corporate espionage or blackmail.

The issue of Bluesnarfing prompted manufacturers and developers to take action. The Bluetooth Special Interest Group (Bluetooth SIG), the organisation responsible for developing and standardising Bluetooth technology, released security advisories and guidelines to address the vulnerability. Device manufacturers released firmware updates and patches to fix security flaws and enhance the overall security of Bluetooth implementations. As a result of these efforts, Bluesnarfing has become less prevalent and is considered less of an issue for modern devices.

Bluebugging is a form of Bluetooth attack where an attacker gains full control over a Bluetooth-enabled device, allowing them to access and modify information, use the device to make calls, send text messages, and even connect to the internet. This is a much more severe and invasive threat than Bluesnarfing and Bluejacking, given the level of control it provides to the attacker.

Executing a Bluebugging attack is similar to Bluesnarfing, beginning with identifying an active, vulnerable Bluetooth device within range. The attacker then exploits vulnerabilities in the Bluetooth implementation of the device, often by tricking the user into believing they are pairing with a trusted device or brute forcing a Bluetooth pairing PIN on an implementation that does not prompt the user for confirmation. Once access is gained, the attacker can essentially control the device as if it were their own.

The impact of Bluebugging can be severe, given the comprehensive control it provides to the attacker. Personal information such as contact details, messages, and emails can be accessed and modified, or the device can be used to make calls or send messages. Additionally, the device’s microphone and camera can be remotely operated, turning the device into a covert listening device.

Maintaining device security, keeping devices updated with the latest firmware and security patches, and following recommended security practices to mitigate potential risks associated with Bluebugging and other Bluetooth-related vulnerabilities remains crucial.

Bluesmacking is a denial-of-service (DoS) attack targeting Bluetooth-enabled devices. The attack exploits a vulnerability in the L2CAP Bluetooth protocol to transfer large packets, taking advantage of the limited processing capabilities of certain devices. Bluesmacking attacks were primarily executed using specialised software tools that generated and transmitted many Bluetooth packets.

Modern Bluetooth devices have implemented improved firmware and software solutions that enable better handling and filtering of Bluetooth packets. These enhancements have significantly reduced the effectiveness of BlueSmacking attacks and made it less of an issue for modern devices.

As we delve deeper into the realm of Bluetooth hacking, it's essential to understand that the landscape has evolved significantly since the days of legacy attacks such as Bluesnarfing or Bluejacking. While these older attacks have offered valuable lessons in cybersecurity, hackers are constantly devising newer and more sophisticated techniques to exploit Bluetooth vulnerabilities.

This page shifts our focus from legacy to modern Bluetooth hacking methods. We'll examine several modern attacks, including BlueBorne, Key Negotiation of Bluetooth (KNOB) Attack, and Bluetooth Impersonation AttackS (BIAS).

BlueBorne, an attack discovered in 2017, emerged as a substantial threat in the field of cybersecurity, presenting hackers with the ability to exploit Bluetooth connections and gain complete control over targeted devices. The wide-ranging nature of the BlueBorne attack vector poses a significant risk to the vast array of devices equipped with Bluetooth capabilities. From conventional computers and mobile devices extending to IoT devices such as televisions, watches, cars, and medical appliances. What sets BlueBorne apart is its capability to compromise devices without requiring them to be paired or set on discoverable mode. The research team at Armis Labs, who unearthed this vulnerability, identified eight zero-day vulnerabilities associated with BlueBorne, revealing the existence of this attack vector and its potential impact. However, numerous other vulnerabilities are believed to remain undiscovered in various Bluetooth-enabled platforms.

These vulnerabilities have been extensively researched and confirmed to be operational, highlighting the significant risk BlueBorne poses. Exploiting these vulnerabilities, hackers can execute remote code on targeted devices and even carry out Man-in-The-Middle attacks. The versatility of the BlueBorne attack vector allows for a wide range of offences, making it a potent threat to device security and user privacy.

Blueborne stands as a stark reminder of the vulnerabilities present in Bluetooth technology. Its discovery led to increased awareness and emphasised the need for robust security measures in Bluetooth-enabled devices.

The Key Negotiation of Bluetooth (KNOB) attack represents a sophisticated and potentially devastating form of Bluetooth hacking. It exploits a flaw in the Bluetooth standard to undermine the encryption of Bluetooth connections. This vulnerability was discovered by three researchers: Daniele Antonioli from the Singapore University of Technology and Design, Nils Ole Tippenhauer from CISPA Helmholtz Center for Information Security, and Kasper Rasmussen from the University of Oxford. They published their findings, Key Negotiation of Bluetooth (KNOB) Attack, in 2019.

Bluetooth connections rely on an encrypted link using a shared encryption key. During the setup of this encrypted link, both devices agree on the encryption key's length. The vulnerability that the KNOB attack exploits lies in this negotiation process.

The attacker intercepts the Bluetooth pairing communication and forcibly sets the length of the encryption key to its minimum allowed size, which is only one byte. With such a weak encryption key, it becomes trivial for the attacker to crack it through brute force methods, thereby gaining access to the encrypted communication.

One crucial aspect of the KNOB attack is that it does not require knowledge of any previously shared link key, making it an entirely new attack methodology compared to previous attacks on Bluetooth encryption.

Essentially all devices that adhere to the Bluetooth standard, including smartphones, tablets, laptops, and IoT devices, could be vulnerable to a KNOB attack. The inherent issue lies within the Bluetooth standard itself rather than specific implementations, making it a broad-spectrum vulnerability.

Following its discovery, patches were developed and rolled out to fix this issue in many devices. The best way to protect against a KNOB attack is by ensuring all your Bluetooth-capable devices are updated with the latest software and firmware. Moreover, the Bluetooth Special Interest Group (SIG), which oversees the Bluetooth standard's development, has updated the standard to require a minimum encryption key length of seven bytes going forward.

Bluetooth Impersonation AttackS (BIAS) is a novel attack discovered in 2020 discovered, again by Daniele Antonioli, Nils Ole Tippenhauer, and Kasper Rasmussen, and published in BIAS: Bluetooth Impersonation AttackS.

The BIAS attack targets the secure, simple pairing and connection processes employed by devices implementing the Bluetooth BR/EDR (Basic Rate/Enhanced Data Rate) specification or Bluetooth Classic. This attack method enables the attacker to authenticate themselves by connecting with a victim's device and masquerading as a device already paired with the victim's.

The core vulnerability lies in the fact that during this impersonation process, the Bluetooth protocol does not require mutual authentication - it only requires that the device initiating the connection verifies the other party. This means that a malicious actor can impersonate a Bluetooth device without knowing the long-term key shared by the impersonated device.

Once this impersonation is successful, attackers can access critical functions such as reading and writing data on the victim's device or even establishing a full-fledged Man-in-The-Middle (MITM) attack.

BIAS attacks are potentially effective against any device using the Bluetooth BR/EDR specification, including smartphones, tablets, laptops, and certain IoT devices. Since this attack method exploits fundamental protocol weaknesses, it is agnostic to the device type or manufacturer.

BIAS attacks can be mitigated through firmware updates that address the specific vulnerabilities in the Bluetooth Classic protocol. Therefore, ensuring that your devices are up-to-date with their latest firmware and software updates is crucial in defending against BIAS attacks.

Following best practices and implementing security measures is crucial to mitigate the risks of Bluetooth technology. The following recommendations can help users enhance the security of their Bluetooth-enabled devices:

Keep Devices Updated: Ensure you update the firmware and software of your Bluetooth-enabled devices regularly. Manufacturers frequently release updates and patches to address security vulnerabilities and enhance device security.Disable Bluetooth When Not Needed: If you're not actively using Bluetooth, switch it off or disable it on your devices. You minimise potential attack opportunities by keeping Bluetooth off when it's not in use. This simple action can significantly lower the risk of unauthorised access and potential exploitation of Bluetooth vulnerabilities.Enable Device Pairing Authorisation: Modern devices typically have this setting enabled by default, but older devices might default to automatic pairing without authorisation. Activate device pairing authorisation on your Bluetooth-enabled devices. This feature necessitates devices to be authenticated and authorised before forming a connection. Enabling this setting helps prevent unauthorised devices from accessing your Bluetooth-enabled devices, thereby protecting them from potential attacks.Limit Device Visibility: Set your device to be invisible or undiscoverable when it's not being used to restrict its visibility to potential attackers.Exercise Caution in Public Settings: Exercise caution when using Bluetooth in public spaces. Do not pair with or accept connection requests from unknown devices. Attackers might exploit Bluetooth vulnerabilities in crowded places or public networks to gain unauthorised device access.Cryptanalysis is a fascinating and essential facet of cybersecurity that delves into the intricate world of cyphers and codes. It is the art and science of breaking ciphertext, cyphers and cryptosystems - essentially, Cryptanalysis is the process of decrypting coded or encrypted data without access to the key used in the encryption process.

The primary objective of Cryptanalysis is not just to decode encrypted data. Its broader goal encompasses assessing and assuring the strength of encryption techniques and ensuring that information remains secure from potential threats or utilising the same techniques on an adversary to break encryption.

In cryptography, plain text refers to the original, readable message or data that needs to be encrypted. The cypher text is the scrambled, unreadable form of the plain text resulting from an encryption algorithm. The transformation from plain text to cypher text, and vice versa, is controlled by a key. A key is a piece of information used in the encryption and decryption process. In symmetric encryption, the same key is used for encryption and decryption, while asymmetric encryption uses a public key for encryption and a private key for decryption.

Cryptanalysis employs a variety of techniques to break a cryptographic system:

Frequency Analysis: This technique is based on the statistical study of the letters or symbols in the cypher text. If the frequency of characters in the cypher text matches the frequency of letters in the language of the plain text, it can give clues to the substitution or transposition methods used.Pattern Finding: If certain groups of characters or patterns reoccur in the cypher text, they may represent the same plain text segments, providing hints about the structure of the key or the encryption algorithm.Brute Force Attacks: These attacks try all possible keys until the correct one is found. Although this method is guaranteed to find the key eventually, it is computationally expensive and becomes impractical as the key size increases.The history of Cryptanalysis is as extensive as it is fascinating.

Cryptography itself has its roots in ancient civilisations. In Egypt around 1900 BC, non-standard hieroglyphs in an inscription showcased an early instance of encryption. The Greeks then developed cryptographic tools like the Scytale for transposition cyphers and steganography - hiding messages in plain sight. Given the utilisation of such techniques, it's plausible to presume that some individuals sought to decipher these rudimentary encryptions.

However, the first recorded instance of Cryptanalysis came from the Arabic scientist Al-Kindi (also known as Alkindus in the West). He wrote a book on decrypting encrypted code, introducing the first recorded frequency analysis method. This technique, which involves counting the occurrences of letters or groups of letters in a ciphertext, remains one of the fundamental tools in cryptanalysis.

During the Renaissance, The Italian scholar Giovanni Battista della Porta wrote "De Furtivis Literarum Notis", aka "On the Hidden Notes of Letters", a pioneering collection of work on the subject. In the book (separated into related volumes, common for scholarly works at the time), he formalised a collection of known cyphers and encryption methodologies and explored methods and linguistic peculiarities that can be used to help break them.

In both World Wars, cryptanalysis proved to be an essential part of military strategy. World War II, in particular, witnessed massive strides in cryptanalysis with the breaking of the German Enigma machine cypher at Bletchley Park. This achievement, led by British cryptanalyst Alan Turing and his team, significantly influenced the war's course and simultaneously laid significant groundwork for modern computers.

The advent of digital computers and the Internet heralded a new era for Cryptanalysis. Modern encryption algorithms are exponentially more complex than their classic counterparts.

Previous Mark Complete & NextNext \

Cryptanalysis Side-Channel Attacks refer to a category of cryptographic attacks that exploit information inadvertently leaked during the execution of cryptographic algorithms.

Contrary to traditional cryptanalysis, which concentrates on identifying flaws in the mathematical algorithms employed in cryptography, side-channel attacks aim at the physical implementation of these systems. These attacks leverage indirect information such as timing data, power usage, electromagnetic emissions, and acoustic signals rather than confronting the incredibly complex mathematical elements of the algorithms. As a result, side-channel attacks could potentially circumvent robust cryptographic algorithms that are immune to conventional cryptanalysis techniques.

Side-channel attacks can primarily be classified into two types:

Passive Side-Channel Attacks: In this scenario, the attacker monitors the system without actively interfering. The data leakage stems from the system's natural functioning. This could include observing aspects such as power consumption, timing, or electromagnetic emissions.Active Side-Channel Attacks: The attacker deliberately manipulates the system to provoke informative alterations. This could involve manipulating the system's power supply or introducing particular inputs to observe output or operation time changes.There are several common forms of side-channel attacks.

Timing attacks are a type of side-channel attack where an attacker gains information about a cryptographic system based on the amount of time the system takes to process different inputs. In these attacks, the attacker measures the computation time of cryptographic algorithms and makes informed guesses about the secret key based on the observed variations.

Timing attacks exploit the fact that different operations and instructions may take different amounts of time to execute on a computer. If the time taken to perform an operation depends on the value of the secret key, then measuring the operation's execution time can reveal information about the key.

For instance, consider an encryption algorithm that uses the secret key bit by bit. If the algorithm takes noticeably longer when processing a '1' bit than a ‘0’ bit, an attacker could determine the key's value by measuring the time taken for each bit processed.

Paul Kocher demonstrated one of the earliest and most notable instances of timing attacks in 1996 against SSL-enabled web servers in a paper presented at the CRYPTO 1996 conference titled Timing Attacks on Implementations of Diffie-Hellman, RSA, DSS, and Other Systems.

The HTTPs/TLS Attacks Module delves further into attacks on HTTP secure communications.

RSA uses modular exponentiation for encryption and decryption. The time taken for these operations can vary based on the values of the exponent (private key). Kocher's attack method involved measuring the time taken to decrypt several ciphertexts. This information was then used to infer the private key bit by bit, leading to a full compromise of the key.

Mitigation of timing attacks often involves the use of constant-time algorithms. These algorithms are designed to run for the same amount of time, regardless of the input or any secret information (like a key). By removing the correlation between data-dependent computation times and secret information, constant-time algorithms help defend against timing attacks.

Power-monitoring attacks, aka power analysis attacks, are a type of side-channel attack that exploit the variations in a device's power consumption to extract sensitive information. These attacks are based on the observation of the power consumption of a device during the execution of cryptographic operations. This power usage can be directly measured from the device’s power line. Advanced statistical techniques are then used to analyse these power traces and extract the secret keys.

There are two main types of power-monitoring attacks:

Simple Power Analysis (SPA): In this form, the attacker directly interprets the power consumption graph to identify operations. For instance, a spike in power use could indicate a specific operation, revealing a bit of the secret key.Differential Power Analysis (DPA): This method is more sophisticated and involves collecting power consumption data for many operations and using statistical analysis to find correlations between power consumption and the values of bits in the secret key.Power-monitoring attacks have been successful in real-world applications. In 1999, Paul Kocher, Joshua Jaffe, and Benjamin Jun demonstrated the first public Differential Power Analysis attack at the CRYPTO 1999 conference in a paper titled Differential Power Analysis. Their method involved monitoring a smart card's power consumption while performing encryption operations. By carefully analysing this power usage data across many operations, they were able to extract the secret encryption keys stored on the card successfully.

Mitigating power-monitoring attacks can be complex as it often involves a combination of hardware and software countermeasures. Power regulation and randomisation techniques can be employed on the hardware side to make power analysis more difficult. On the software side, measures include designing cryptographic algorithms so that the power consumption does not correlate with the operations performed, thus obfuscating any information leakage.

Acoustic cryptanalysis is a type of side-channel attack where an adversary seeks to extract sensitive information from a system by analysing the sound emissions it produces during its operation. These sound emissions often correlate with different internal states or operations of the system, allowing attackers to gain insights into the data being processed.

For instance, the sound produced by a computer's CPU, fans, and other components can change based on the computations it's performing. Likewise, the acoustic emissions of typing on a keyboard can vary with different keys, which can be exploited through keyboard eavesdropping. If these computations involve secret data like encryption keys or the user typing sensitive information, analysing the sound can reveal this data.

Daniel Genkin, Adi Shamir (the 'S' in RSA), and Eran Tromer demonstrated a significant instance of acoustic cryptanalysis at the CRYPTO 2014 conference in a paper titled, RSA Key Extraction via Low-Bandwidth Acoustic Cryptanalysis. They found that different RSA secret keys cause a computer's CPU to emit different high-frequency acoustic signals, enabling an attacker to extract the keys by using a nearby mobile phone.

Georgi Gerganov presents an intriguing proof of concept for keyboard eavesdropping, named Keytap, on his GitHub. Keytap utilises a microphone to record the unique sounds produced by each key on a mechanical keyboard, thereby replicating keystrokes. This technique could potentially capture sensitive information such as private key passwords.

Preventing acoustic cryptanalysis involves both hardware and software countermeasures. On the hardware side, methods can include using sound-absorbing materials in device construction or physically isolating sensitive components to reduce sound emissions. On the software side, mitigation strategies may include programming systems to avoid performing operations that result in recognisable sound patterns when handling sensitive data. Another method is introducing random noise into the computation process to make acoustic analysis more challenging.

Microprocessors, the (electronically) pulsating heart of our computers and digital devices, are not infallible. They can contain flaws or vulnerabilities that attackers can exploit to perform unauthorised actions within a computer system. These vulnerabilities range from simple design flaws to complex security loopholes.

In some cases, these vulnerabilities are unintentional, arising from oversights or errors in the design process. In other instances, they may be deliberately introduced as backdoors to allow certain users unauthorised access. Regardless of their origin, all microprocessor vulnerabilities pose a risk to the security and integrity of our digital systems.

A microprocessor is an integrated circuit (IC) that encapsulates the functions of a central processing unit (CPU) on a single silicon chip. A microprocessor is a type of CPU, but not all CPUs are microprocessors. For example, the CPU in a mainframe computer is typically implemented using multiple ICs, while the CPU in a personal computer is typically implemented using a single microprocessor. Its role is to fetch, decode, and execute instructions, facilitating various computational and control tasks.

The functional architecture of a microprocessor revolves around several essential components, including the control unit (CU), the arithmetic logic unit (ALU), and an Instruction Set Architecture (ISA), among others.

control unit is part of a computer's CPU that directs the operation of the processor. It tells the computer's memory, arithmetic/logic unit and input and output devices how to respond to the instructions that have been sent to the processor.arithmetic logic unit is a major component of the computer system's central processing unit (CPU), or the 'brain'. It performs arithmetic and logic operations, which are fundamental functions of computers.Instruction Set Architecture is an abstract model of a computer that defines the supported data types, the register set, what memory addressing modes are available, and the instruction set or the set of machine-language commands that the computer can understand and execute.Transistors, the fundamental building blocks of a microprocessor, play a crucial role in its operation. These tiny electronic switches can turn the flow of electricity on or off, representing binary states, i.e., 1s and 0s. In the fetch-decode-execute cycle, transistors function to store and manipulate the binary data during the execution of instructions. The control unit uses combinations of these binary values to represent different commands and data. The arithmetic logic unit uses transistors based on these binary instructions to perform arithmetic and logical operations. The more transistors a microprocessor contains, the more instructions it can process, enhancing its speed and performance.

Microprocessor design is a multifaceted discipline that incorporates several stages, each of which can bear upon the potential vulnerability of the resulting system. Amongst others, these stages include architectural design, logic design, circuit design, physical design, and verification,

Architectural design, the first phase of microprocessor design, refers to the formulation of the processor's architectural specifications, which involves deciding the instruction set architecture. The design choices made in this phase significantly impact the microprocessor's performance, power efficiency, and cost. For instance, selecting a CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computer) or RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer) architecture can dramatically influence the complexity and speed of the processor. In short, CISC is like a Swiss Army Knife with many tools in one package, while RISC is like a specialist tool designed to do one thing very well.

Next is the logic design stage, where the specifications defined in the architectural design are translated into concrete logic operations. Here, digital logic principles and Boolean algebra are used to create a detailed schematic of logic gates. This process includes creating the data path (which performs arithmetic and logical operations) and control units (which orchestrate data flow). The end result is a register-transfer level (RTL) description that serves as a blueprint for circuit design.

Circuit design entails converting the RTL into specific electronic circuits. This involves choosing circuit-level implementations for each logic gate using transistors, resistors, and capacitors. The goal is to optimise circuits for factors like speed, power consumption, and silicon area. For instance, an AND gate can be implemented using two transistors in a series configuration.

The physical design stage involves defining the spatial layout of components on the silicon chip. This process includes placement (deciding where each component should go) and routing (determining the paths for electrical connectivity). Here, factors like heat dissipation and power distribution need careful consideration because they significantly impact chip reliability and performance.

The last phase is verification, a crucial step to ensure the microprocessor performs as intended. Formal methods are used to prove or disprove the correctness of a system against a certain specification. This includes static timing analysis to ensure all logic functions correctly within the defined clock cycle time. Verification helps identify and rectify potential issues before mass fabrication, saving time and cost.

It should be noted that while the design process has the potential to introduce vulnerabilities, it also provides opportunities for embedding security features into the microprocessor.

Microprocessor Optimization Strategies are the various methods and techniques to enhance the performance and efficiency of a microprocessor. These strategies focus on improving processing speed, reducing power consumption, and enhancing other crucial aspects like instruction execution and data handling.

Pipelining is a crucial strategy used to improve the throughput of instruction execution. It involves breaking down the execution of instructions into discrete stages that can be processed simultaneously. Each instruction is fed through the pipeline stage-by-stage sequentially, akin to an assembly line in a manufacturing plant.

The main stages of an instruction pipeline typically include instruction fetch, instruction decode, execute, memory access, and write back. By allowing multiple instructions to be at different stages of execution simultaneously, pipelining significantly increases the instruction throughput and utilisation of the processor's resources.

Speculative Execution is an optimisation method used to boost processing speed. This technique is based on making educated guesses about the potential direction a program might take, particularly when faced with a conditional branch instruction - a juncture where the program can follow different paths based on a specific condition.

Instead of waiting to determine the correct path (which can cause delays), the microprocessor will predict the most likely path and execute instructions along that pathway. If this prediction is correct, it results in substantial time savings and increases overall performance. However, this method requires an efficient rollback mechanism. If the prediction is incorrect, the microprocessor must discard the speculatively executed instructions, revert to its pre-speculation state, and resume along the correct path.

Caching is a technique employed to speed up memory access. As fetching data from the main memory is time-consuming, microprocessors use caches, which are small, high-speed memory units placed between the CPU and the main memory. They store frequently or recently accessed data, enabling quicker retrieval when needed.

Caches are usually organised in a hierarchy of levels (L1, L2, L3), with L1 being the smallest and fastest and directly interfacing with the CPU, while the lower levels are larger and slower. Caching is crucial for performance but can also be a source of security vulnerabilities. Cache-based side-channel attacks, for instance, deduce sensitive data by observing timing differences in memory access, which are influenced by the state of the cache.

Microprocessor vulnerabilities refer to the weaknesses or flaws in the design or implementation of microprocessors that can be exploited to compromise the security of a computing system. These vulnerabilities can manifest across various layers of the microprocessor's operational stack, from its hardware foundations to its firmware interfaces and the software it executes.

One widely recognised class of microprocessor vulnerabilities pertains to side-channel attacks. These exploit indirect information leakages, such as timing information, power consumption, or electromagnetic emissions. An infamous example of a side-channel attack is the Spectre and Meltdown vulnerabilities discovered in 2018.

Microprocessor vulnerabilities represent a significant concern due to these components’ critical role in modern computational infrastructure, from personal devices and embedded systems to servers and data centres. Their study and mitigation have become important areas of focus within cybersecurity.

Spectre is a class of microprocessor vulnerabilities that was publicly disclosed in 2018. Officially identified as CVE-2017-5753 (bounds check bypass, Spectre-V1) and CVE-2017-5715 (branch target injection, Spectre-V2).

Spectre was independently discovered and reported by Jann Horn from Google Project Zero and Paul Kocher. Kocher collaborated with several others, including Daniel Genkin, Mike Hamburg, Moritz Lipp, and Yuval Yarom.

Spectre is unique in that it breaks the isolation between different applications, allowing an attacker to trick error-free programs into leaking their secrets. Spectre takes advantage of the speculative execution technique used in modern microprocessors.

In a normal scenario, if the processor's predictions are accurate, the speculatively executed instructions are committed, and their results are used. If the predictions are wrong, the instructions and their direct effects are discarded to maintain program correctness. Herein lies the catch. Despite discarding the direct effects of incorrect speculative execution, subtle, indirect effects may persist, particularly in micro-architectural structures like the cache.

The Spectre vulnerability intentionally causes the processor to make incorrect predictions which initiate the speculative execution of a specially chosen set of instructions. These instructions are designed to deliberately modify the state of the processor in a way that wouldn't happen under normal conditions. For example, they could cause specific data to be loaded into the cache that wouldn't usually be there.

Although these manipulated instructions and their immediate outcomes are discarded when the processor detects the incorrect prediction, the modifications made to the cache remain.

However, attackers still cannot directly access this data; they need to use a side-channel attack to infer what data has been loaded into the cache, revealing potentially sensitive data, which should have been secure and inaccessible.

The Spectre vulnerability thus represents a potent exploit that leverages a fundamental performance feature of modern microprocessors, turning it into a channel for information leakage.

The most immediate consequence of Spectre is its potential to compromise the security of computing systems. By exploiting speculative execution, Spectre enables an attacker to read sensitive information from the memory of other programs running on the same system, including potential passwords, encryption keys, and other confidential data. This represents a severe violation of the fundamental security principle of process isolation.

Meltdown, officially identified as CVE-2017-5754, is a severe microprocessor vulnerability that was publicly disclosed in 2018, alongside the aforementioned Spectre vulnerabilities.

Meltdown was independently discovered and reported by three teams: Jann Horn from Google Project Zero; Werner Haas and Thomas Prescher from Cyberus Technology; and Daniel Gruss, Moritz Lipp, Stefan Mangard, and Michael Schwarz from Graz University of Technology.

Unlike Spectre, which breaks the isolation between different applications, Meltdown dissolves the more fundamental isolation between user applications and the operating system. This allows a malicious program to access the memory of other programs and the operating system, potentially gaining access to sensitive information.

The key to the Meltdown vulnerability is its exploitation of a feature of modern microprocessors known as out-of-order execution. This is a performance-enhancing technique in which the processor executes instructions not in the sequential order in which they appear in the program but in an order dictated by the availability of input data and execution units, thereby maximising resource utilisation and throughput. However, while the final results of execution are committed in order, the effects of instructions executed out-of-order can still be observed in the processor's micro-architectural state, even if these instructions are later rolled back.

Meltdown leverages this characteristic in a specific way. It begins by inducing an exception — for example, by attempting to access a privileged memory location that is off-limits to user programs. While handling this exception would usually involve discarding the effects of the offending instruction, the out-of-order execution allows further instructions that depend on this illegal access to be executed before the exception is handled.

For instance, one such instruction could load data from the privileged memory location (referenced indirectly via the exception-causing instruction) into the cache. Even though the exception is subsequently handled and the effects of the offending instruction are discarded, the changes to the cache remain. Then by using a side-channel attack — specifically, a cache timing attack — the attacker can infer the data that was loaded into the cache and, as a result, the contents of the privileged memory location.

This vulnerability is critical because it undermines kernel/user space isolation, a cornerstone of operating system security.

Like Spectre, Meltdown illustrates the potential security risks that can arise from the pursuit of performance in microprocessor design and the complex interplay between hardware and software in modern computing systems.

Meltdown's most immediate and severe impact is its potential to compromise the security of computing systems. Meltdown breaks the fundamental security boundary between user applications and the operating system kernel, potentially allowing a malicious application to read sensitive kernel memory, including personal data, passwords, and cryptographic keys.

Both Spectre and Meltdown are critical vulnerabilities in microprocessors that exploit performance-enhancing features of processor architecture, specifically speculative execution and out-of-order execution. While they share certain characteristics, there are notable differences in their mechanics and potential impacts.

Spectre and Meltdown exploit different aspects of modern processor design. Spectre (CVE-2017-5753 and CVE-2017-5715) capitalises on speculative execution.

Meltdown (CVE-2017-5754), on the other hand, exploits out-of-order execution.

Spectre breaks the isolation between different applications, allowing an attacker to trick error-free programs into leaking their secrets, potentially leading to cross-process, virtual machine, or sandbox escape attacks. It is more difficult to exploit than Meltdown but also harder to mitigate completely.

Conversely, Meltdown breaks the isolation between user applications and the operating system, allowing a program to access the memory of other programs and the operating system. This can lead to severe violations of system integrity and confidentiality. Meltdown is easier to mitigate with techniques like Kernel Page Table Isolation (KPTI), but these mitigations can carry significant performance overheads.

Mitigation strategies for Spectre and Meltdown have been a subject of intense research and development since their disclosure. Both hardware and software-based solutions have been proposed and implemented.

The primary objective of these mitigation techniques is to prevent unauthorised access to sensitive data by exploiting the vulnerabilities without significantly compromising system performance; a task easier said than done.

Retpoline is an effective mitigation technique for Spectre. Replacing potentially hazardous indirect software branches prevents the speculative execution that Spectre exploits.

An indirect software branch refers to a type of program instruction that guides the execution path based on specific conditions. Unlike a direct branch, where the destination is pre-determined and known in advance, the destination of an indirect branch is determined dynamically during runtime.

The fundamental idea behind retpoline is to modify the control flow so that speculative execution is avoided when encountering indirect branches.

Instead of using traditional branch instructions that attackers can manipulate to leak sensitive information, retpolines rely on a sequence of instructions that redirect the program flow without allowing speculative execution to take place. However, retpolines may impose a performance overhead, particularly in applications with many indirect branches.

Changes to how compilers generate code can also help mitigate Spectre. For instance, by introducing specific code constructs or instructions known as barriers.

Memory Barriers (or Fence Instructions) ensure that all load and store memory operations before the barrier are completed before any operations that come after the barrier. They're used to maintain consistency and prevent undesired reordering of memory accesses by the compiler or processor.

Branch Prediction Barriers are used to inhibit speculative execution at certain points in the code where it could lead to a security vulnerability. By limiting branch prediction and speculative execution, they help reduce the potential for malicious activities.

The purpose of these barriers is to enforce strict control over the flow of execution, disallowing the processor from executing instructions speculatively. Compilers can safeguard critical code sections against Spectre attacks by strategically adding these barriers.

KPTI is the primary mitigation technique against Meltdown. It isolates the kernel's page table from the page tables of user space processes to prevent any potential information leakage from kernel memory. However, this technique can introduce performance overheads due to increased context switch times.

CPU manufacturers have issued Microcode updates to enable CPUs to implement more fine-grained control and restrictions on speculative execution. This allows the operating system to apply stricter measures and prevent the exploitation of Meltdown-like vulnerabilities at the hardware level.

The Spectre and Meltdown vulnerabilities have brought forth a critical juncture in microprocessor design, highlighting the inextricable link between high-performance computing and security. These vulnerabilities, hinged on the performance optimisation features that define modern microprocessors, have uncovered the inherent security risks in present designs.

While effective, the mitigation techniques employed thus far, including retpoline, compiler modifications, Kernel Page Table Isolation, and microcode updates, have demonstrated the limitations and trade-offs that must be navigated to secure systems. While they mitigate the immediate risks of Spectre and Meltdown, they do not entirely eliminate them nor prevent the emergence of new variants.