Following the Fundamentals of AI module, this module takes a more practical approach to applying machine learning techniques. Instead of focusing solely on theory, you will now engage in hands-on activities that involve building and evaluating real models. Throughout this process, you will gain experience with the end-to-end workflow of AI development, from exploring datasets to training and testing models.

You will construct three distinct AI models in this module:

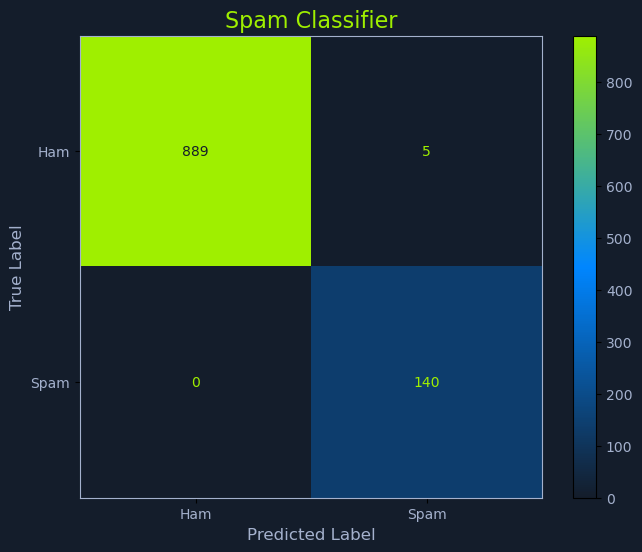

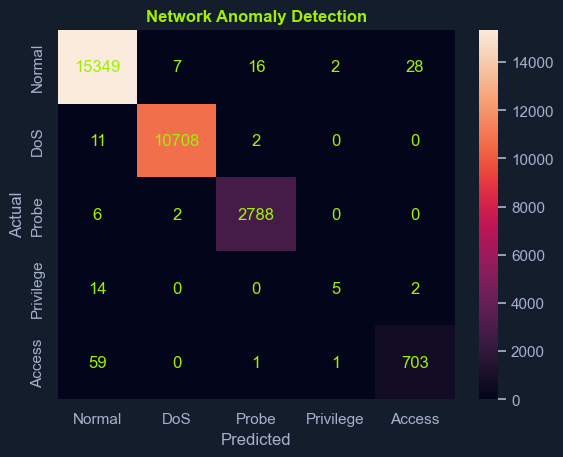

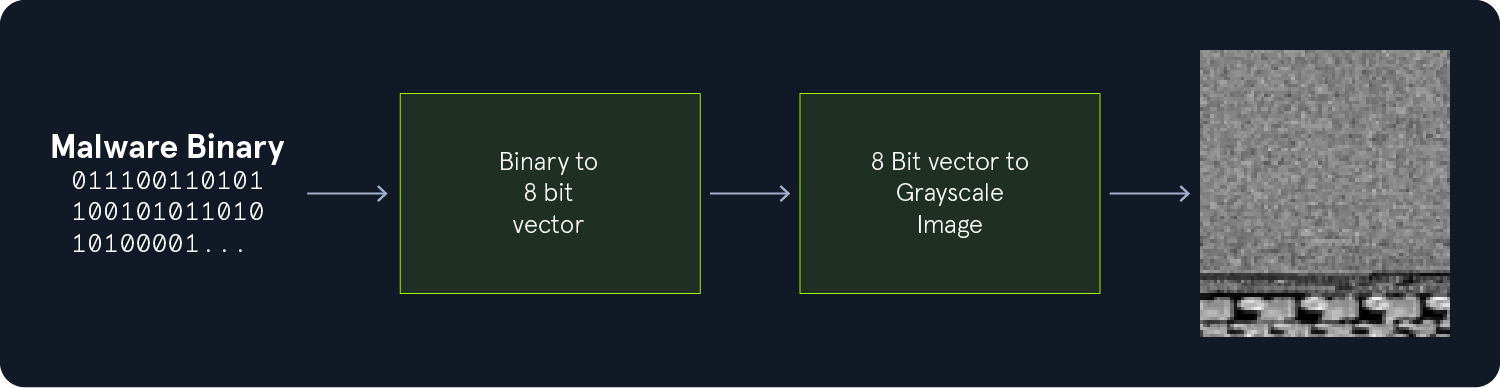

Spam Classifier to determine whether an SMS message is spam or not.Network Anomaly Detection Model designed to identify abnormal or potentially malicious network traffic.Malware Classifier using byteplots, which are visual representations of binary data.Throughout the module, you will encounter python code blocks that guide you step-by-step through the model-building process.

You will learn more about Jupyter later in this module, but for now, understand that you can copy and paste these code snippets into a Jupyter notebook to execute them in sequence, either in the playground VM, or your environment.

You can train most of these models in your own environment. For a decent experience, you will need at least 4GB of RAM and at least 4 CPU cores.

Note: Throughout this module, all sections marked as interactive contain code blocks for you to follow along. Not all interactive sections contain separate exercises.

Setting up a proper environment is essential before diving into the exciting world of AI. This module offers two paths for an enviroment.

The first is The Playground. Because we acknowledge that not everyone will have the computer resources required to build the models in this module, we have provided a Virtual Playground Environment for you to use if you absolutely need it.

Because this is separate from PwnBox, there are specific sections where you can spawn this VM. You can connect to it using your HTB VPN profile or PwnBox. The VM exposes Jupyter for you to work in, which will be covered in the next section, but you can access it on http://<VM-IP>:8888. You can spawn the VM and extend instance time if needed at the bottom of this section or any of the Model Evaluation sections in the module.

:arrow-circle-left: :arrow-right: :redo: :home::bars:

Note: While the Playground environment is sufficient to follow along with everything discussed in this module, it lacks in performance to provide an environment that encourages experimentation. Therefore, we recommend setting up an environment on your own system, provided you have sufficiently powerful hardware. This will result in shorter training times and enable experimentation with different parameters, resulting in a more enjoyable way to work through the module and improve your understanding of the performance impact of different training parameters.

The second is to set up an environment on your own system, which you can do by following the rest of this section. For this module you will need at least 4GB of RAM. In a majority of cases, your own environment will provide faster training times than the playground VM.

Miniconda is a minimal installer for the Anaconda distribution of the Python programming language. It provides the conda package manager and a core Python environment without automatically installing the full suite of data science libraries available in Anaconda. Users can selectively install additional packages, creating a customized environment that aligns with their specific needs.

Both Miniconda and Anaconda rely on the conda package manager, allowing for simplified installation, updating, and management of Python packages and their dependencies. In essence, Miniconda offers a lighter starting point, while Anaconda comes pre-loaded with a broader range of commonly used data science tools.

You might wonder why we use Miniconda instead of a standard Python installation. Here are a few compelling reasons:

Performance: Miniconda often performs data science and machine learning tasks better due to optimized packages and libraries.Package Management: The Conda package manager simplifies package installation and management, ensuring compatibility and resolving dependencies. This is particularly crucial in deep learning, where projects often rely on a complex web of interconnected libraries.Environment Isolation: Miniconda allows you to create isolated environments for different projects. This prevents conflicts between packages and ensures each project has its dedicated dependencies.By using Miniconda, you'll streamline your workflow, avoid compatibility issues, and ensure that your deep learning environment is optimized for performance and efficiency.

While the traditional installer works well, we can streamline the process on Windows using Scoop, a command-line installer for Windows. Scoop simplifies the installation and management of various applications, including Miniconda.

First, install Scoop. Open PowerShell and run:

Environment Setup

C:\> Set-ExecutionPolicy RemoteSigned -scope CurrentUser # Allow scripts to run

C:\> irm get.scoop.sh | iex

Next, add the extras bucket, which contains Miniconda:

Environment Setup

C:\> scoop bucket add extras

Finally, install Miniconda with:

Environment Setup

C:\> scoop install miniconda3

This command installs the latest Python 3 version of Miniconda.

To verify the installation, close and reopen PowerShell. Type conda --version to check if Miniconda is installed correctly.

Environment Setup

C:\> conda --version

conda 24.9.2

Homebrew, a popular package manager for macOS, simplifies software installation and keeps it up-to-date. It also provides a convenient way for macOS users to install Miniconda.

If you don't have Homebrew, install it first by pasting the following command in your terminal:

Environment Setup

root@htb[/htb]$ /bin/bash -c "$(curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Homebrew/install/HEAD/install.sh)"

Once Homebrew is set up, you can install Miniconda with this simple command:

Environment Setup

root@htb[/htb]$ brew install --cask miniconda

This command installs the latest version of Miniconda with Python 3.

To verify the installation, close and reopen your terminal. Type conda --version to confirm that Miniconda is installed correctly.

Environment Setup

root@htb[/htb]$ conda --version

conda 24.9.2

Miniconda provides a straightforward installation process that relies not solely on a distribution’s package manager. You can obtain the latest Miniconda installer directly from the official repository, run it silently, and then load the conda environment for your user shell. This approach ensures that conda commands and environments are readily available without manual configuration.

Environment Setup

root@htb[/htb]$ wget https://repo.anaconda.com/miniconda/Miniconda3-latest-Linux-x86_64.sh

root@htb[/htb]$ chmod +x Miniconda3-latest-Linux-x86_64.sh

root@htb[/htb]$ ./Miniconda3-latest-Linux-x86_64.sh -b -u

root@htb[/htb]$ eval "$(/home/$USER/miniconda3/bin/conda shell.$(ps -p $$ -o comm=) hook)"

Confirm that Miniconda is installed correctly by running:

Environment Setup

root@htb[/htb]$ conda --version

conda 24.9.2

The init command configures your shell to recognize and utilize conda. This step is essential for:

Activating environments: Allows you to use conda activate to switch between environments.Using conda commands: Ensures that conda commands are available in your shell.To initialize conda for your shell, run the following command after installing Miniconda:

Environment Setup

root@htb[/htb]$ conda init

This command will modify your shell configuration files (e.g., .bashrc or .zshrc) to include the necessary conda settings. You might need to close and reopen your terminal for the changes to take effect.

Finally, run these two commands to complete the init process

Environment Setup

root@htb[/htb]$ conda config --add channels defaults

root@htb[/htb]$ conda config --add channels conda-forge

root@htb[/htb]$ conda config --add channels nvidia # only needed if you are on a PC that has a nvidia gpu

root@htb[/htb]$ conda config --add channels pytorch

root@htb[/htb]$ conda config --set channel_priority strict

After installing Miniconda, you'll notice that the base environment is activated by default every time you open a new terminal. This is indicated by the (base) prefix on your path.

Environment Setup

(base) $

While this can be useful, it's often preferable to start with a clean slate and activate environments only when needed. Personally, I wouldn't say I like seeing the (base) prefix all the time, either.

To prevent the base environment from activating automatically, you can use the following command:

Environment Setup

root@htb[/htb]$ conda config --set auto_activate_base false

This command modifies the condarc configuration file and disables the automatic activation of the base environment.

When you open a new terminal, you won't see the (base) prefix in your prompt anymore.

In software development, managing dependencies can quickly become a complex task, especially when working on multiple projects with different library requirements.

This is where virtual environments come into play. A virtual environment is an isolated space where you can install packages and dependencies specific to a particular project, without interfering with other projects or your system's global Python installation.

They are critical for AI tasks for a few reasons:

Dependency Isolation: Each project can have its own set of dependencies, even if they conflict with those of other projects.Clean Project Structure: Keeps your project directory clean and organized by containing all dependencies within the environment.Reproducibility: Ensures that your project can be easily reproduced on different systems with the same dependencies.System Stability: Prevents conflicts with your global Python installation and avoids breaking other projects.conda provides a simple way to create virtual environments. For example, to create a new environment named ai with Python 3.11, use the following command:

Environment Setup

root@htb[/htb]$ conda create -n ai python=3.11

This will create a virtual environment, ai, which can then be used to contain all ai-related packages.

To activate the myenv environment, use:

Environment Setup

root@htb[/htb]$ conda activate ai

You'll notice that your terminal prompt now includes the environment name in parentheses (ai), indicating that the environment is active. Any packages you install using conda or pip will now be installed within this environment.

To deactivate the environment, use:

Environment Setup

root@htb[/htb]$ conda deactivate

The environment name will disappear from your prompt, and you'll be back to your base Python environment.

With your Miniconda environment set up, you can install the essential packages for your AI journey. These packages generally cover what will be needed in this module.

While conda provides a broad range of packages through its curated channels, it may not include every tool you require. In such cases, you can still use pip within the conda environment. This approach ensures you can install any additional packages that conda does not cover.

Use the conda install command to install the following core packages:

Environment Setup

root@htb[/htb]$ conda install -y numpy scipy pandas scikit-learn matplotlib seaborn transformers datasets tokenizers accelerate evaluate optimum huggingface_hub nltk category_encoders

root@htb[/htb]$ conda install -y pytorch torchvision torchaudio pytorch-cuda=12.4 -c pytorch -c nvidia

root@htb[/htb]$ pip install requests requests_toolbelt

conda provides a method to keep conda-managed packages up to date. Running the following command updates all conda-installed packages within the (ai) environment, but it does not update packages installed with pip. Any pip-installed packages must be managed separately, and mixing pip and conda installations may increase the risk of dependency conflicts.

Environment Setup

root@htb[/htb]$ conda update --all

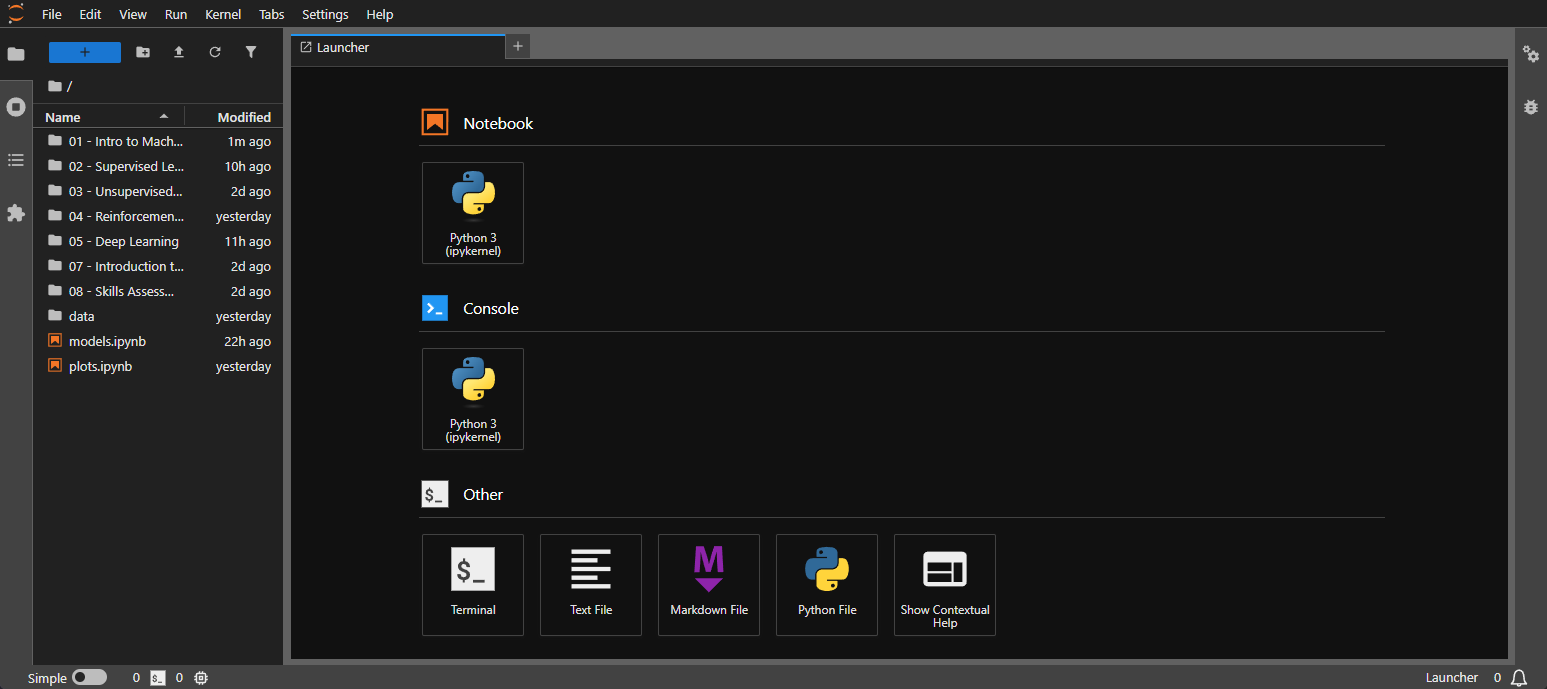

JupyterLab is an interactive development environment that provides web-based coding, data, and visualization interfaces. Due to its flexibility and interactive features, it's a popular choice for data scientists and machine learning practitioners.

Interactive Environment: JupyterLab allows running code in individual cells, facilitating experimentation and iterative development.Data Exploration and Visualization: It integrates seamlessly with libraries like matplotlib and seaborn for creating visualizations and exploring data.Documentation and Sharing: JupyterLab supports markdown and LaTeX for creating rich documentation and sharing code with others.JupyterLab can be easily installed using conda, if it isn't already installed:

JupyterLab

root@htb[/htb]$ conda install -y jupyter jupyterlab notebook ipykernel

Make sure you are running the command from within your ai environment.

To start JupyterLab, simply run:

JupyterLab

root@htb[/htb]$ jupyter lab

This will open a new tab in your web browser with the JupyterLab interface.

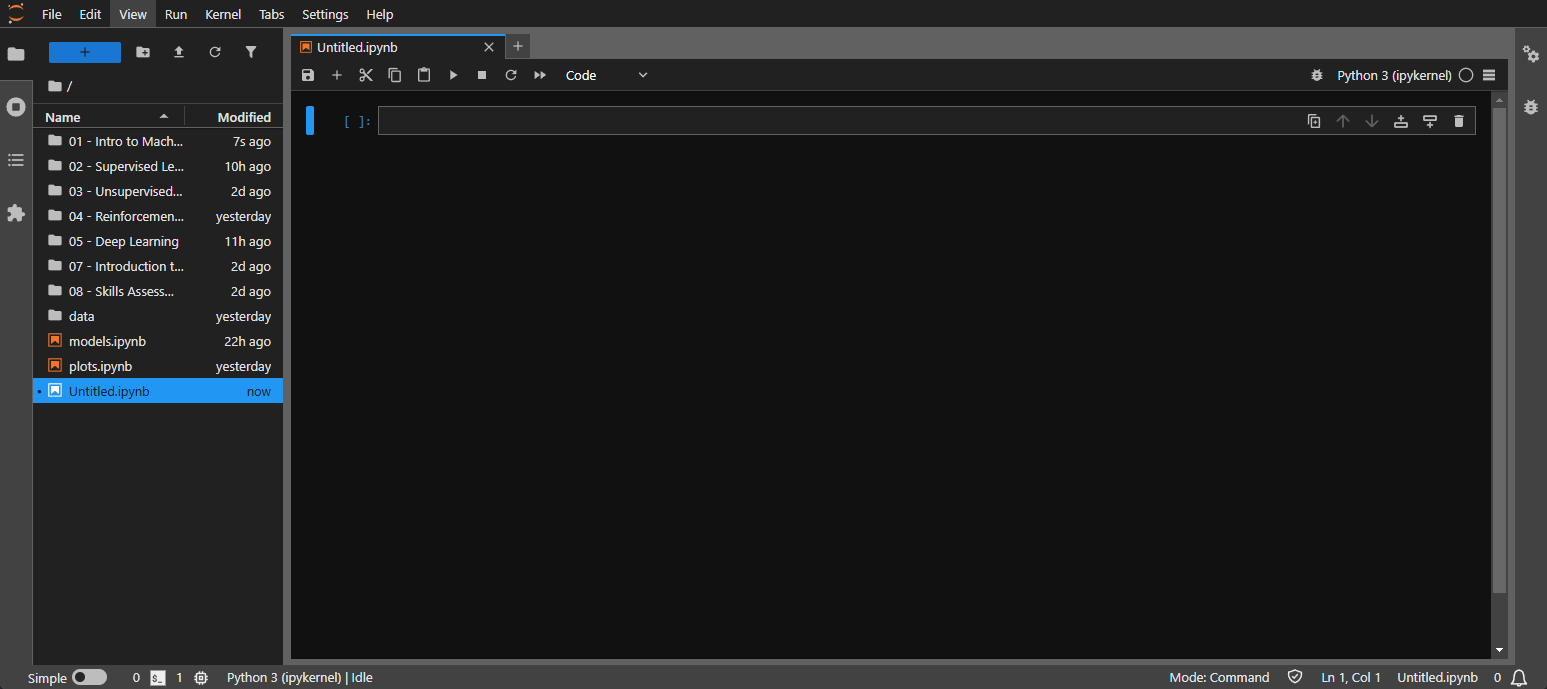

JupyterLab's primary component is the notebook, which allows combining code, text, and visualizations in a single document. Notebooks are organized into cells, where each cell can contain either code or markdown text.

Code cells: Execute code in various languages (Python, R, Julia).Markdown cells: Create formatted text, equations, and images using markdown syntax.Raw cells: Untyped raw text.Click the "Python 3" icon under the "Notebook" section in the Launcher interface to create a new notebook. This will open a notebook with a single empty code cell.

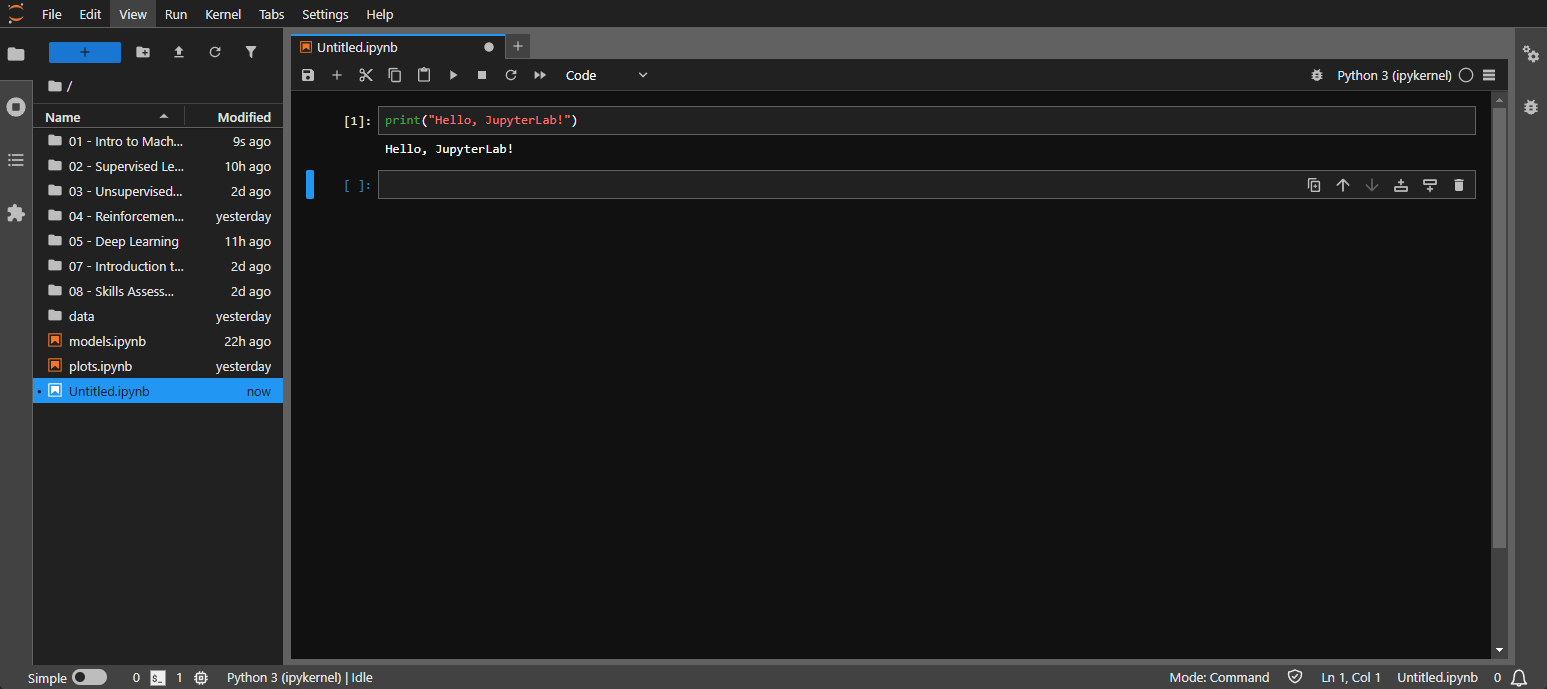

Type your Python code into the code cell and press Shift + Enter to execute it. For example:

Code: python

print("Hello, JupyterLab!")

The output of the code will appear below the cell.

Jupyter notebooks use a stateful environment, which means that variables, functions, and imports defined in one cell remain available to all later cells. Once you execute a cell, any changes it makes to the environment, such as assigning new variables or redefining functions, persist as long as the kernel is running. This differs from a stateless model, where each code execution is isolated and does not retain information from previous executions.

Being aware of the stateful nature of a notebook is important. For example, if you execute cells out of order, you might observe unexpected results due to previously defined or modified variables. Similarly, re-importing modules or updating variable values affects subsequent cell executions, but not those that were previously run.

Say you have a cell that does this:

Code: python

x = 1

then in a later cell you might have:

Code: python

print(x) # This will print '1' because 'x' was defined previously.

If you change the first cell to:

Code: python

x = 2

and re-run it before running the print(x) cell, the value of x in the environment becomes 2, so the output will now be different when you run the print cell.

Click the "+" button in the toolbar to add new cells. You can choose between code cells and markdown cells using the Dropdown on the toolbar. Markdown cells allow you to write formatted text and include headings, lists, and links.

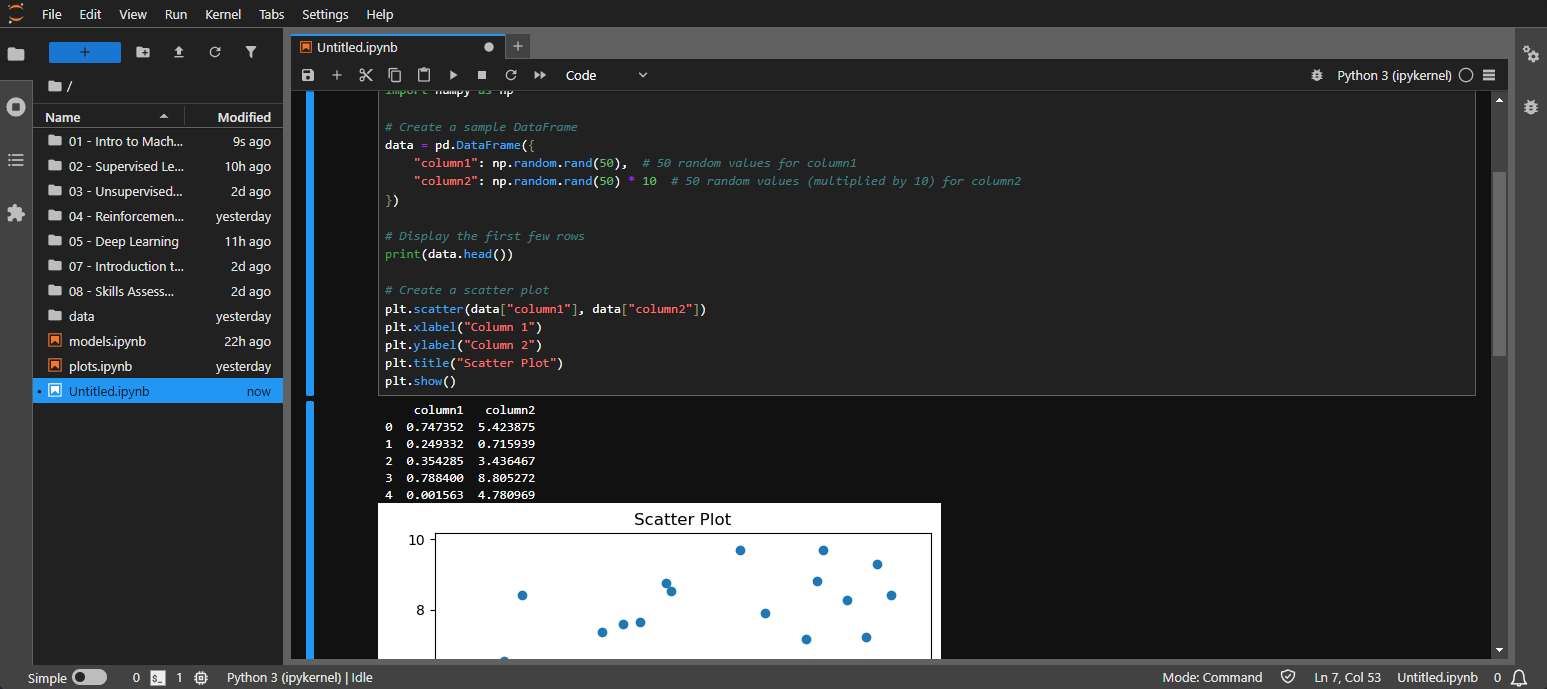

JupyterLab integrates with libraries like pandas, matplotlib, and seaborn for data exploration and visualization. Here's an example of loading a dataset with pandas and creating a simple plot:

Code: python

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

# Create a sample DataFrame

data = pd.DataFrame({

"column1": np.random.rand(50), # 50 random values for column1

"column2": np.random.rand(50) * 10 # 50 random values (multiplied by 10) for column2

})

# Display the first few rows

print(data.head())

# Create a scatter plot

plt.scatter(data["column1"], data["column2"])

plt.xlabel("Column 1")

plt.ylabel("Column 2")

plt.title("Scatter Plot")

plt.show()

This code now generates a sample DataFrame with two columns, column1 and column2, containing random values. The rest of the code remains the same, demonstrating how to display the DataFrame's contents and create a scatter plot using the generated data.

To save your notebook, click the save icon in the toolbar or use the Ctrl + S shortcut. Don't forget to rename your Notebook. You can right-click on the Notebook tab or the Notebook in the file browser.

JupyterLab uses a kernel to run your code. The kernel is a separate process responsible for executing code and maintaining the state of your computations. Sometimes, you may need to reset your environment if it becomes cluttered with variables or you encounter unexpected behavior.

Restarting the kernel clears all variables, functions, and imported modules from memory, allowing you to start fresh without shutting down JupyterLab entirely.

To restart the kernel:

Kernel menu in the top toolbar.Restart Kernel to reset the environment while preserving cell outputs, or Restart Kernel and Clear All Outputs to also remove all previously generated outputs from the notebook.After restarting, re-run any cells containing variable definitions, imports, or computations to restore the environment. This ensures that the notebook state accurately reflects the code you have most recently executed.

This is just a brief overview of Jupyter to get you up and running for this module. For an in-depth guide, refer to the JupyerLab Documentation.

Python is a versatile programming language widely used in Artificial Intelligence (AI) due to its rich library ecosystem that provides efficient and user-friendly tools for developing AI applications. This section focuses on two prominent Python libraries for AI development: Scikit-learn and PyTorch.

Just a quick note. This section provides a high-level overview of key Python libraries for AI, aiming to familiarize you with their purpose, structure, and common use cases. It offers a foundation for identifying relevant APIs and understanding the general landscape of these libraries. The official documentation will be your best resource to learning every small detail about the libraries. You do not need to copy and run these code snippets.

Scikit-learn is a comprehensive library built on NumPy, SciPy, and Matplotlib. It offers a wide range of algorithms and tools for machine learning tasks and provides a consistent and intuitive API, making implementing various machine learning models easy.

Supervised Learning: Scikit-learn provides a vast collection of supervised learning algorithms, including:Linear RegressionLogistic RegressionSupport Vector Machines (SVMs)Decision TreesNaive BayesEnsemble Methods (e.g., Random Forests, Gradient Boosting)Unsupervised Learning: It also offers various unsupervised learning algorithms, such as:Clustering (K-Means, DBSCAN)Dimensionality Reduction (PCA, t-SNE)Model Selection and Evaluation: Scikit-learn includes tools for model selection, hyperparameter tuning, and performance evaluation, enabling developers to optimize their models effectively.Data Preprocessing: It provides functionalities for data preprocessing, including:Scikit-learn offers a rich set of tools for preprocessing data, a crucial step in preparing data for machine learning algorithms. These tools help transform raw data into a suitable format that improves the accuracy and efficiency of models.

Feature scaling is essential to ensure that all features have a similar scale, preventing features with larger values from dominating the learning process. Scikit-learn provides various scaling techniques:

StandardScaler : Standardizes features by removing the mean and scaling to unit variance.MinMaxScaler : Scales features to a given range, typically between 0 and 1.RobustScaler : Scales features using statistics that are robust to outliers.Code: python

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

scaler = StandardScaler()

X_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X)

Categorical features, representing data in categories or groups, need to be converted into numerical representations for machine learning algorithms to process them. Scikit-learn offers encoding techniques:

OneHotEncoder : Creates binary (0 or 1) columns for each category.LabelEncoder : Assigns a unique integer to each category.Code: python

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder

encoder = OneHotEncoder()

X_encoded = encoder.fit_transform(X)

Real-world datasets often contain missing values. Scikit-learn provides methods to handle these missing values:

SimpleImputer : Replaces missing values with a specified strategy (e.g., mean, median, most frequent).KNNImputer : Imputes missing values using the k-Nearest Neighbors algorithm.Code: python

from sklearn.impute import SimpleImputer

imputer = SimpleImputer(strategy='mean')

X_imputed = imputer.fit_transform(X)

Scikit-learn offers tools for selecting the best model and evaluating its performance.

Splitting data into training and testing sets is crucial to evaluating the model's generalization ability to unseen data.

Code: python

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2)

Cross-validation provides a more robust evaluation by splitting the data into multiple folds and training/testing on different combinations.

Code: python

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

scores = cross_val_score(model, X, y, cv=5)

Scikit-learn provides various metrics to evaluate model performance:

accuracy_score : For classification tasks.mean_squared_error : For regression tasks.precision_score, recall_score, f1_score : For classification tasks with imbalanced classes.Code: python

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

accuracy = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred)

Scikit-learn follows a consistent API for training and predicting with different models.

Create an instance of the desired model with appropriate hyperparameters.

Code: python

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

model = LogisticRegression(C=1.0)

Train the model using the fit() method with the training data.

Code: python

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

Make predictions on new data using the predict() method.

Code: python

y_pred = model.predict(X_test)

PyTorch is an open-source machine learning library developed by Facebook's AI Research lab. It provides a flexible and powerful framework for building and deploying various types of machine learning models, including deep learning models.

Deep Learning: PyTorch excels in deep learning, enabling the development of complex neural networks with multiple layers and architectures.Dynamic Computational Graphs: Unlike static computational graphs used in libraries like TensorFlow, PyTorch uses dynamic computational graphs, which allow for more flexible and intuitive model building and debugging.GPU Support: PyTorch supports GPU acceleration, significantly speeding up the training process for computationally intensive models.TorchVision Integration: TorchVision is a library integrated with PyTorch that provides a user-friendly interface for image datasets, pre-trained models, and common image transformations.Automatic Differentiation: PyTorch uses autograd to automatically compute gradients, simplifying the process of backpropagation.Community and Ecosystem: PyTorch has a large and active community, leading to a rich ecosystem of tools, libraries, and resources.At the heart of PyTorch lies the concept of dynamic computational graphs. A dynamic computational graph is created on the fly during the forward pass, allowing for more flexible and dynamic model building. This makes it easier to implement complex and non-linear models.

Tensors are multi-dimensional arrays that hold the data being processed. They can be constants, variables, or placeholders. PyTorch tensors are similar to NumPy arrays but can run on GPUs for faster computation.

Code: python

import torch

# Creating a tensor

x = torch.tensor([1.0, 2.0, 3.0])

# Tensors can be moved to GPU if available

if torch.cuda.is_available():

x = x.to('cuda')

PyTorch provides a flexible and intuitive interface for building and training deep learning models. The torch.nn module contains various layers and modules for constructing neural networks.

The Sequential API allows building models layer by layer, adding each layer sequentially.

Code: python

import torch.nn as nn

model = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(784, 128),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(128, 10),

nn.Softmax(dim=1)

)

The Module class provides more flexibility for building complex models with non-linear topologies, shared layers, and multiple inputs/outputs.

Code: python

import torch.nn as nn

class CustomModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super(CustomModel, self).__init__()

self.layer1 = nn.Linear(784, 128)

self.relu = nn.ReLU()

self.layer2 = nn.Linear(128, 10)

self.softmax = nn.Softmax(dim=1)

def forward(self, x):

x = self.layer1(x)

x = self.relu(x)

x = self.layer2(x)

x = self.softmax(x)

return x

model = CustomModel()

PyTorch provides tools for training and evaluating models.

Optimizers are algorithms that adjust the model's parameters during training to minimize the loss function. PyTorch offers various optimizers:

AdamSGD (Stochastic Gradient Descent)RMSpropCode: python

import torch.optim as optim

optimizer = optim.Adam(model.parameters(), lr=0.001)

Loss Functions measure the difference between the model's predictions and the actual target values. PyTorch provides a variety of loss functions:

CrossEntropyLoss : For multi-class classification.BCEWithLogitsLoss : For binary classification.MSELoss : For regression.Code: python

import torch.nn as nn

loss_fn = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

Metrics evaluate the model's performance during training and testing.

AccuracyPrecisionRecallCode: python

def accuracy(output, target):

_, predicted = torch.max(output, 1)

correct = (predicted == target).sum().item()

return correct / len(target)

The training loop updates the model's parameters based on the training data.

Code: python

import torch

epochs = 10

num_batches = 100

for epoch in range(epochs):

for batch in range(num_batches):

# Get batch of data

x_batch, y_batch = get_batch(batch)

# Forward pass

y_pred = model(x_batch)

# Calculate loss

loss = loss_fn(y_pred, y_batch)

# Backward pass and optimization

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

# Optional: print loss or other metrics

if batch % 10 == 0:

print(f'Epoch [{epoch+1}/{epochs}], Batch [{batch+1}/{num_batches}], Loss: {loss.item():.4f}')

PyTorch provides the torch.utils.data.Dataset and DataLoader classes for handling data loading and preprocessing.

Code: python

from torch.utils.data import Dataset, DataLoader

class CustomDataset(Dataset):

def __init__(self, data, labels):

self.data = data

self.labels = labels

def __len__(self):

return len(self.data)

def __getitem__(self, idx):

return self.data[idx], self.labels[idx]

# Example usage

dataset = CustomDataset(data, labels)

dataloader = DataLoader(dataset, batch_size=32, shuffle=True)

PyTorch allows models to be saved and loaded for inference or further training.

Code: python

# Save model

torch.save(model.state_dict(), 'model.pth')

# Load model

model = CustomModel()

model.load_state_dict(torch.load('model.pth'))

model.eval() # Set the model to evaluation mode

In AI, the quality and characteristics of the data used to train models significantly impact their performance and accuracy. Datasets, which are collections of data points used for analysis and model training, come in various forms and formats, each with its own properties and considerations. Data preprocessing is a crucial step in the machine-learning pipeline that involves transforming raw data into a suitable format for algorithms to process effectively.

Datasets are structured collections of data used for analysis and model training. They come in various forms, including:

Tabular Data: Data organized into tables with rows and columns, common in spreadsheets or databases.Image Data: Sets of images represented numerically as pixel arrays.Text Data: Unstructured data composed of sentences, paragraphs, or full documents.Time Series Data: Sequential data points collected over time, emphasizing temporal patterns.The quality of a dataset is fundamental to the success of any data analysis or machine learning project. Here’s why:

Model Accuracy: High-quality datasets produce more accurate models. Poor-quality data—such as noisy, incomplete, or biased datasets—leads to reduced model performance.Generalization: Carefully curated datasets enable models to generalize effectively to unseen data. This minimizes overfitting and ensures consistent performance in real-world applications.Efficiency: Clean, well-prepared data reduces both training time and computational demands, streamlining the entire process.Reliability: Reliable datasets lead to trustworthy insights and decisions. In critical domains like healthcare or finance, data quality directly affects the dependability of results.Several key attributes characterize a good dataset:

| Attribute | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

Relevance |

The data should be relevant to the problem at hand. Irrelevant data can introduce noise and reduce model performance. | Text data from social media posts is more relevant than stock market prices for a sentiment analysis task. |

Completeness |

The dataset should have minimal missing values. Missing data can lead to biased models and incorrect predictions. | Techniques like imputation can handle missing values, but it's best to start with a complete dataset if possible. |

Consistency |

Data should be consistent in format and structure. Inconsistencies can cause errors during preprocessing and model training. | Ensure that date formats are uniform across the dataset (e.g.,YYYY-MM-DD). |

Quality |

The data should be accurate and free from errors. Errors can arise from data collection, entry, or transmission issues. | Data validation and verification processes can help ensure data quality. |

Representativeness |

The dataset should be representative of the population it aims to model. A biased or unrepresentative dataset can lead to biased models. | A facial recognition system's dataset should include a diverse range of faces from different ethnicities, ages, and genders. |

Balance |

The dataset should be balanced, especially for classification tasks. Imbalanced datasets can lead to biased models that perform poorly on minority classes. | Techniques like oversampling, undersampling, or generating synthetic data can help balance the dataset. |

Size |

The dataset should be large enough to capture the complexity of the problem. Small datasets may not provide enough information for the model to learn effectively. | However, large datasets can also be computationally expensive and require more powerful hardware. |

The provided dataset, demo_dataset.csv is a CSV file containing network log entries. Each record describes a network event and includes details such as the source IP address, destination port, protocol used, the volume of data transferred, and an associated threat level. Analyzing these entries allows one to simulate various network scenarios that are useful for developing and evaluating intrusion detection systems.

The dataset consists of multiple columns, each serving a specific purpose:

log_id: Unique identifier for each log entry.source_ip: Source IP address for the network event.destination_port: Destination port number used by the event.protocol: Network protocol employed (e.g., TCP, TLS, SSH).bytes_transferred: Total bytes transferred during the event.threat_level: Indicator of the event's severity. 0 denotes normal traffic, 1 indicates low-threat activity, and 2 signifies a high-threat event.Before processing, it is essential to note potential difficulties:

threat_level column includes unknown values (e.g., ?, -1) that must be standardized or addressed during preprocessing.Acknowledging these challenges early allows the data to be properly cleaned and transformed, facilitating accurate and reliable analysis.

We first load it into a pandas DataFrame to begin working with the dataset. A pandas DataFrame is a flexible, two-dimensional labeled data structure that supports a variety of operations for data exploration and preprocessing. Key advantages include labeled axes, heterogeneous data handling, and integration with other Python libraries.

Utilizing a DataFrame simplifies subsequent tasks like inspection, cleaning, encoding, and data transformation.

Code: python

import pandas as pd

# Load the dataset

data = pd.read_csv("./demo_dataset.csv")

In this code, pd.read_csv("./demo_dataset.csv") loads the downloaded CSV file into a DataFrame named data. From here, inspecting, manipulating, and preparing the dataset for further steps in the analysis pipeline becomes straightforward.

After loading the dataset, we employ various operations to understand its structure, identify anomalies, and determine the nature of cleaning or transformations needed.

We examine the first few rows to get a quick overview, which can help detect obvious issues like unexpected column names, incorrect data types, or irregular patterns.

Code: python

# Display the first few rows of the dataset

print(data.head())

This command outputs the initial rows of the DataFrame, offering an immediate glimpse into the dataset's overall organization.

Understanding the data types and completeness of each column is essential. We can quickly review the dataset's information, including which columns have null values and the total number of entries per column.

Code: python

# Get a summary of column data types and non-null counts

print(data.info())

The info() method reveals the dataset's shape, column names, data types, and how many entries are present for each column, enabling early detection of columns with missing or unexpected data.

Missing values or anomalies must be handled to maintain the dataset's integrity. The next step is to identify how many missing values each column contains.

Code: python

# Identify columns with missing values

print(data.isnull().sum())

This command returns the count of null values for each column, helping to prioritize which features need attention. Addressing these missing values may involve imputation, removal, or other cleaning strategies to ensure the dataset remains reliable and valid for further analysis.

Data preprocessing transforms raw data into a suitable format for machine learning algorithms. Key techniques include:

Data Cleaning: Handling missing values, removing duplicates, and smoothing noisy data.Data Transformation: Normalizing, encoding, scaling, and reducing data.Data Integration: Merging and aggregating data from multiple sources.Data Formatting: Converting data types and reshaping data structures.Effective preprocessing addresses inconsistencies, missing values, outliers, noise, and feature scaling, improving the accuracy, efficiency, and robustness of machine learning models.

In addition to missing values, we need to check for invalid values in specific columns. Here are some common checks for the given dataset.

To identify invalid source_ip values, you can use a regular expression to validate the IP addresses:

Code: python

import re

def is_valid_ip(ip):

pattern = re.compile(r'^((25[0-5]|2[0-4][0-9]|[01]?[0-9][0-9]?)\.){3}(25[0-5]|2[0-4][0-9]|[01]?[0-9][0-9]?)$')

return bool(pattern.match(ip))

# Check for invalid IP addresses

invalid_ips = data[~data['source_ip'].astype(str).apply(is_valid_ip)]

print(invalid_ips)

To identify invalid destination_port values, you can check if the port numbers are within the valid range (0-65535):

Code: python

def is_valid_port(port):

try:

port = int(port)

return 0 <= port <= 65535

except ValueError:

return False

# Check for invalid port numbers

invalid_ports = data[~data['destination_port'].apply(is_valid_port)]

print(invalid_ports)

To identify invalid protocol values, you can check against a list of known protocols:

Code: python

valid_protocols = ['TCP', 'TLS', 'SSH', 'POP3', 'DNS', 'HTTPS', 'SMTP', 'FTP', 'UDP', 'HTTP']

# Check for invalid protocol values

invalid_protocols = data[~data['protocol'].isin(valid_protocols)]

print(invalid_protocols)

To identify invalid bytes_transferred values, you can check if the values are numeric and non-negative:

Code: python

def is_valid_bytes(bytes):

try:

bytes = int(bytes)

return bytes >= 0

except ValueError:

return False

# Check for invalid bytes transferred

invalid_bytes = data[~data['bytes_transferred'].apply(is_valid_bytes)]

print(invalid_bytes)

To identify invalid threat_level values, you can check if the values are within a valid range (e.g., 0-2):

Code: python

def is_valid_threat_level(threat_level):

try:

threat_level = int(threat_level)

return 0 <= threat_level <= 2

except ValueError:

return False

# Check for invalid threat levels

invalid_threat_levels = data[~data['threat_level'].apply(is_valid_threat_level)]

print(invalid_threat_levels)

There are a few different ways we can approach this bad data.

The most straightforward approach is to discard the invalid entries entirely. This ensures that the remaining dataset is clean and free of potentially misleading information.

Code: python

# the ignore errors covers the fact that there might be some overlap between indexes that match other invalid criteria

data = data.drop(invalid_ips.index, errors='ignore')

data = data.drop(invalid_ports.index, errors='ignore')

data = data.drop(invalid_protocols.index, errors='ignore')

data = data.drop(invalid_bytes.index, errors='ignore')

data = data.drop(invalid_threat_levels.index, errors='ignore')

print(data.describe(include='all'))

This method is generally preferred when data accuracy is paramount, and the loss of some data points does not significantly compromise the overall analysis. However, it may not always be feasible, especially if the dataset is small or the invalid entries constitute a substantial portion of the data.

After dropping the bad data from our dataset, we are only left with 77 clean entries.

It is sometimes possible to clean or transform invalid entries into valid and usable data instead of discarding them. This approach aims to retain as much information as possible from the dataset.

Imputing is the process of replacing missing or invalid values in a dataset with estimated values. This is crucial for maintaining the integrity and usability of the data, especially in machine learning and data analysis tasks where missing values can lead to biased or inaccurate results.

First, convert all invalid or corrupted entries, such as MISSING_IP, INVALID_IP, STRING_PORT, UNUSED_PORT, NON_NUMERIC, or ?, into NaN. This approach standardizes the representation of missing values, enabling uniform downstream imputation steps.

Code: python

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import re

from ipaddress import ip_address

df = pd.read_csv('demo_dataset.csv')

invalid_ips = ['INVALID_IP', 'MISSING_IP']

invalid_ports = ['STRING_PORT', 'UNUSED_PORT']

invalid_bytes = ['NON_NUMERIC', 'NEGATIVE']

invalid_threat = ['?']

df.replace(invalid_ips + invalid_ports + invalid_bytes + invalid_threat, np.nan, inplace=True)

df['destination_port'] = pd.to_numeric(df['destination_port'], errors='coerce')

df['bytes_transferred'] = pd.to_numeric(df['bytes_transferred'], errors='coerce')

df['threat_level'] = pd.to_numeric(df['threat_level'], errors='coerce')

def is_valid_ip(ip):

pattern = re.compile(r'^((25[0-5]|2[0-4][0-9]|[01]?\d?\d)\.){3}(25[0-5]|2[0-4]\d|[01]?\d?\d)$')

if pd.isna(ip) or not pattern.match(str(ip)):

return np.nan

return ip

df['source_ip'] = df['source_ip'].apply(is_valid_ip)

After this step, NaN represents all missing or invalid data points.

For basic numeric columns like bytes_transferred, use simple methods such as the median or mean. For categorical columns like protocol, use the most frequent value.

Code: python

from sklearn.impute import SimpleImputer

numeric_cols = ['destination_port', 'bytes_transferred', 'threat_level']

categorical_cols = ['protocol']

num_imputer = SimpleImputer(strategy='median')

df[numeric_cols] = num_imputer.fit_transform(df[numeric_cols])

cat_imputer = SimpleImputer(strategy='most_frequent')

df[categorical_cols] = cat_imputer.fit_transform(df[categorical_cols])

These imputations ensure that all columns have valid, non-missing values, though they do not consider complex relationships among features.

For more sophisticated scenarios, employ advanced techniques like KNNImputer or IterativeImputer. These methods consider relationships among features to produce contextually meaningful imputations.

Code: python

from sklearn.impute import KNNImputer

knn_imputer = KNNImputer(n_neighbors=5)

df[numeric_cols] = knn_imputer.fit_transform(df[numeric_cols])

After cleaning and imputations, apply domain knowledge. For source_ip values that remain missing, assign a default such as 0.0.0.0. Validate protocol values against known valid protocols. For ports, ensure values fall within the valid range 0-65535, and for protocols that imply certain ports, consider mode-based assignments or domain-specific mappings.

Code: python

valid_protocols = ['TCP', 'TLS', 'SSH', 'POP3', 'DNS', 'HTTPS', 'SMTP', 'FTP', 'UDP', 'HTTP']

df.loc[~df['protocol'].isin(valid_protocols), 'protocol'] = df['protocol'].mode()[0]

df['source_ip'] = df['source_ip'].fillna('0.0.0.0')

df['destination_port'] = df['destination_port'].clip(lower=0, upper=65535)

Perform final verification steps to confirm that distributions are reasonable and categorical sets remain valid. Adjust imputation strategies and transformations or remove problematic records if anomalies persist.

Code: python

print(df.describe(include='all'))

Data transformations improve the representation and distribution of features, making them more suitable for machine learning models. These transformations ensure that models can efficiently capture underlying patterns by converting categorical variables into machine-readable formats and addressing skewed numerical distributions. They also enhance trained models' stability, interpretability, and predictive performance.

Encoding converts categorical values into numeric form so machine learning algorithms can utilize these features. Depending on the situation, you can choose:

OneHotEncoder for binary indicator features that represent each category separately.LabelEncoder for integer codes, though this may imply unintended order.HashingEncoder or frequency-based methods to handle high-cardinality features and control feature space size.After encoding, verify that the transformed features are meaningful and do not introduce artificial ordering.

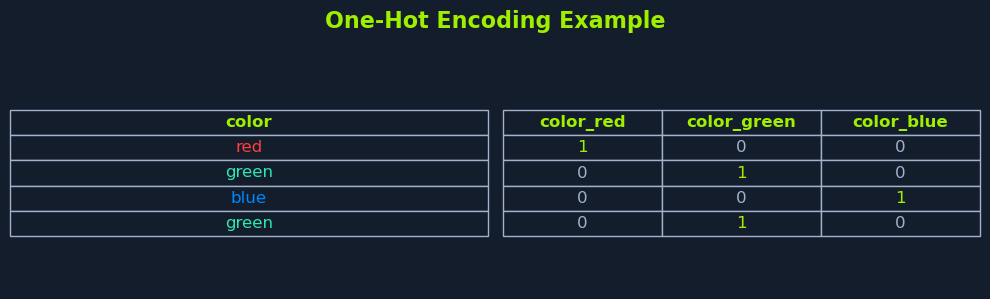

One-hot encoding takes a categorical feature and converts it into a set of new binary features, where each binary feature corresponds to one possible category value. This process creates a set of indicator columns that hold 1 or 0, indicating the presence or absence of a particular category in each row.

For example, consider the categorical feature color, which can take on the values red, green, or blue. In a dataset, you might have rows where color is red in one instance, green in another, and so on. By applying one-hot encoding, instead of keeping a single column with values like red, green, or blue, the encoding creates three new binary columns:

color_redcolor_greencolor_blueEach of these new columns corresponds to one of the original categories. If a row had color set to red, the color_red column for that row would be 1, and the other two columns (color_green and color_blue) would be 0. Similarly, if color was originally green, then the color_green column would be 1, while the color_red and color_blue columns would be 0.

This approach prevents models from misinterpreting category values as numeric hierarchies. However, it can increase the number of features if a category has many unique values.

In this case, we are going to encode the protocol feature.

Code: python

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder

encoder = OneHotEncoder(handle_unknown='ignore', sparse_output=False)

encoded = encoder.fit_transform(df[['protocol']])

encoded_df = pd.DataFrame(encoded, columns=encoder.get_feature_names_out(['protocol']))

df = pd.concat([df.drop('protocol', axis=1), encoded_df], axis=1)

The original protocol feature is replaced with distinct binary columns, ensuring the model interprets each category independently.

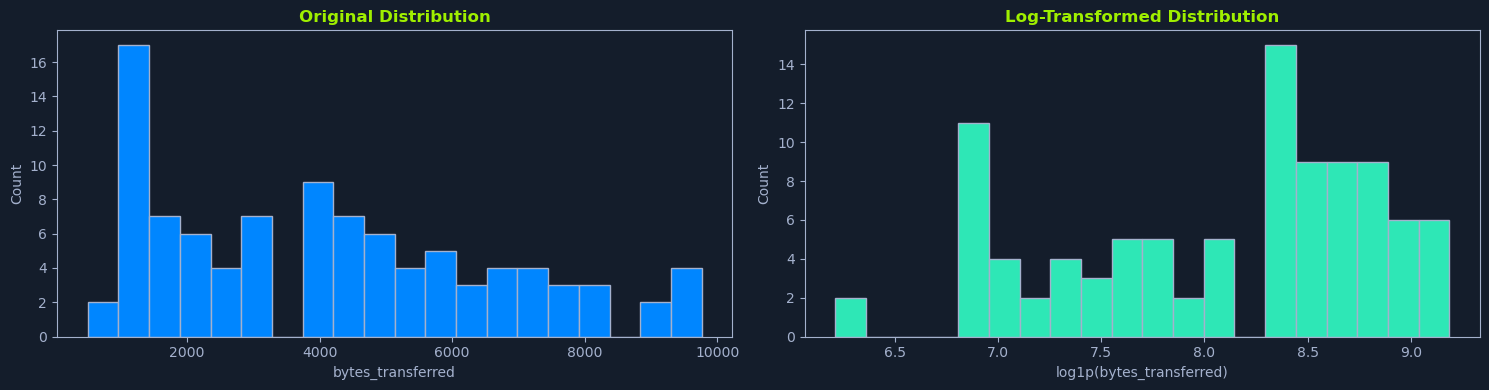

When a feature is skewed, its values are unevenly distributed, often with most observations clustered near one end and a few extreme values stretching out the distribution. Such skew can affect the performance of machine learning models, especially those sensitive to outliers or that assume more uniform or normal-like data distributions.

Scaling or transforming these skewed features helps models better capture patterns in the data. One common transformation is applying a log transform to compress large values more than small ones, resulting in a more balanced distribution and less dominated by outliers. By doing this, models often gain improved stability, accuracy, and generalization ability.

Below, we show how to apply a log transform using the log1p function. This approach adds 1 to each value before taking the log, ensuring that the transform is defined even for values at or near zero.

Code: python

import numpy as np

# Apply logarithmic transformation to a skewed feature to reduce its skewness

df["bytes_transferred"] = np.log1p(df["bytes_transferred"]) # Add 1 to avoid log(0)

The code above transforms the bytes_transferred feature. Before this transformation, the feature might have had a few very large values, overshadowing the majority of smaller observations. After the transformation, the distribution is evener, helping the model treat all data points fairly and reducing the risk of overfitting outliers.

Visual comparisons of the distribution before and after the transform (as shown by the above figure) confirm that the original skew has been substantially reduced. Although no information is lost, the model now views the data through a lens that downplays extreme cases and highlights underlying patterns more clearly.

Data splitting involves dividing a dataset into three distinct subsets—training, validation, and testing—to ensure reliable model evaluation. By having separate sets, you can train your model on one subset, fine-tune it on another, and finally test its performance on data it has never seen before.

Training Set: Used to fit the model. Typically accounts for around 60-80% of the entire dataset.Validation Set: Used for tuning hyperparameters and model selection. Often around 10-20% of the entire dataset.Test Set: Used only after all model selections and tuning are complete. Often around 10-20% of the entire dataset.The code below demonstrates one approach using train_test_split from scikit-learn. The initial split allocates 80% of the data for training and 20% for testing. A subsequent split divides the 80% training portion into 60% for final training and 20% for validation.

Note that test_size=0.25 in the second split refers to 25% of the previously created training subset (which is 80% of the data). In other words, 0.8 × 0.25 = 0.2 (20% of the entire dataset), leaving 60% for training and 20% for validation overall.

Code: python

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Separate features (X) and target (y)

X = df.drop("threat_level", axis=1)

y = df["threat_level"]

# Initial split: 80% training, 20% testing

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=1337)

# Second split: from the 80% training portion, allocate 60% for final training and 20% for validation

X_train, X_val, y_train, y_val = train_test_split(X_train, y_train, test_size=0.25, random_state=1337)

These subsets support a structured workflow:

X_train and y_train.X_val and y_val.X_test and y_test.When assessing a trained machine learning model, one examines a set of numerical metrics to gauge how well the model performs on a given task. These metrics often quantify the relationship between predictions and known ground-truth labels.

In the Fundamentals of AI module, we briefly covered metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, and we know that these metrics provide different perspectives on model behavior.

Accuracy is the proportion of correct predictions out of all predictions made. It measures how often the model classifies instances correctly. A model with accuracy: 0.9950 indicates that it makes correct predictions 99.50% of the time.

Key points about accuracy:

(true positives + true negatives) / (all instances).While accuracy appears intuitive, relying on it alone can hide important details. Consider a spam classification scenario where only 1% of incoming emails are spam and 99% are legitimate. A model that always predicts every email as legitimate will achieve accuracy: 0.99, but it will never catch any spam.

In this case, accuracy fails to highlight the model’s inability to correctly identify the minority class. This underscores the importance of complementary metrics, such as precision, recall, or F1-score, which provide a more nuanced understanding of performance when dealing with imbalanced datasets.

Precision measures how often the model’s predicted positives are truly positive. For precision: 0.9949, when the model labels an instance as positive, it is correct 99.49% of the time.

Key points about precision:

true positives / (true positives + false positives).precision reduces wasted effort caused by false alarms.With the spam classification example, if the model labels 100 emails as spam, and 99 of them are actually spam, then its precision is high. This reduces the inconvenience of losing important, legitimate emails to the spam folder. However, if the model rarely identifies spam in the first place, it may fail to catch a large portion of malicious emails. High precision alone does not guarantee that the model is finding all the spam it should.

Recall measures the model’s ability to identify all positive instances. For recall: 0.9950, the model detects 99.50% of all positives.

Key points about recall:

true positives / (true positives + false negatives).recall reduces the risk of missing critical cases.In the spam classification scenario, a model with high recall correctly flags most spam emails. This helps ensure that suspicious content does not slip through unnoticed. However, a model with very high recall but low precision might flood the spam folder with benign emails. Although it rarely misses spam, it inconveniences the user by misclassifying too many legitimate emails as spam.

F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. For F1-score: 0.9949, the metric indicates a near-perfect balance between these two aspects.

Key points about F1-score:

precision and recall.2 * (precision * recall) / (precision + recall).Continuing with the spam classification scenario, the F1-score ensures that the model not only minimizes the misclassification of legitimate emails (high precision) but also effectively identifies the majority of spam messages (high recall). By focusing on the balance rather than just one metric, the F1-score provides a more complete picture of the model’s performance in identifying and correctly handling both spam and non-spam emails.

While these four metrics are common, other measures may provide further insights:

Specificity: Measures how effectively the model identifies negatives.AUC: The Area Under the ROC Curve, indicating the model’s discriminative capability at various thresholds.Matthews Correlation Coefficient: Useful for highly imbalanced datasets.Confusion Matrix: Summarizes predictions versus true labels, offering a comprehensive view of performance.Such metrics and visualizations help confirm that the given high values truly reflect robust performance, not just favorable conditions in the dataset.

When evaluating a model’s metrics (accuracy: 0.9750, precision: 0.9300, recall: 0.9100, F1-score: 0.9200), consider the following:

Even metrics that look impressive may not fully capture real-world performance if the dataset does not reflect operational conditions. For instance, high accuracy could be achieved if negative cases are heavily overrepresented, making it easier to appear correct by default. Verifying that both precision and recall remain robust helps ensure the model identifies important instances without becoming overwhelmed by incorrect predictions.

Depending on the setting, certain trade-offs emerge:

recall to avoid missing critical threats, even if it occasionally flags benign events.precision can reduce the burden caused by following up on false alarms.These metrics, considered together, provide a balanced perspective. The relatively high and reasonably aligned precision and recall values yield a strong F1-score, suggesting that the model performs consistently well across different classes. This balanced performance supports confidence that the model’s decisions are both reliable and meaningful in practice.

Spam, or unsolicited bulk messaging, has been a persistent issue since the early days of digital communication. It clutters inboxes, poses security risks, and can be used for malicious purposes such as phishing attacks. Effective spam detection is crucial for maintaining the integrity and usability of email systems and other messaging platforms.

Bayes' Theorem is a fundamental concept in probability theory that describes the probability of an event based on prior knowledge of conditions that might be related to the event. Mathematically, it is expressed as:

Code: python

P(A|B) = (P(B|A) * P(A)) / P(B)

Where:

P(A|B) is the probability of event A occurring, given that B is true.P(B|A) is the probability of event B occurring, given that A is true.P(A) is the prior probability of event A.P(B) is the prior probability of event B.In the context of spam detection, A can represent the hypothesis that an email is spam (Spam), and B can represent the observed features of the email (e.g., words, phrases, etc.).

Let's break down how Bayes' Theorem can be applied to determine if an email is spam:

Hypothesis: We want to determine the probability that an email is spam given its features.P(Spam|Features): Probability that an email is spam given its features.Likelihood: This is the probability of observing the features given that the email is spam.P(Features|Spam): Probability of the features appearing in a spam email.Prior Probability: The probability that any email is spam, irrespective of its features.P(Spam): Prior probability of an email being spam.Marginal Likelihood: The total probability of observing the features, considering both spam and non-spam emails.P(Features): Probability of the features appearing in any email.Using Bayes' Theorem, we can express this as:

Code: python

P(Spam|Features) = (P(Features|Spam) * P(Spam)) / P(Features)

Naive Bayes makes the "naive" assumption that the presence of a particular feature in an email is independent of the presence of any other feature, given the class label. This simplifies the calculation of P(Features|Spam):

Code: python

P(Features|Spam) = P(feature1|Spam) * P(feature2|Spam) * ... * P(featureN|Spam)

Similarly, for non-spam emails:

Code: python

P(Features|Not Spam) = P(feature1|Not Spam) * P(feature2|Not Spam) * ... * P(featureN|Not Spam)

Using these probabilities, we can calculate the posterior probability of an email being spam or not spam given its features. The class with the higher posterior probability is chosen as the predicted class.

Suppose we have an email with features F1 and F2. We want to determine if this email is spam.

P(Spam) = 0.3: Prior probability that any email is spam.P(Not Spam) = 0.7: Prior probability that any email is not spam.P(F1|Spam) = 0.4: Probability of feature F1 given the email is spam.P(F2|Spam) = 0.5: Probability of feature F2 given the email is spam.P(F1|Not Spam) = 0.2: Probability of feature F1 given the email is not spam.P(F2|Not Spam) = 0.3: Probability of feature F2 given the email is not spam.Using the Naive Bayes assumption:

Code: python

P(F1, F2|Spam) = P(F1|Spam) * P(F2|Spam) = 0.4 * 0.5 = 0.2

P(F1, F2|Not Spam) = P(F1|Not Spam) * P(F2|Not Spam) = 0.2 * 0.3 = 0.06

Now, applying Bayes' Theorem:

Code: python

P(Spam|F1, F2) = (P(F1, F2|Spam) * P(Spam)) / P(F1, F2)

To find P(F1, F2), we use the law of total probability:

Code: python

P(F1, F2) = P(F1, F2|Spam) * P(Spam) + P(F1, F2|Not Spam) * P(Not Spam)

= (0.2 * 0.3) + (0.06 * 0.7)

= 0.06 + 0.042

= 0.102

Thus:

Code: python

P(Spam|F1, F2) = (0.2 * 0.3) / 0.102

= 0.06 / 0.102

≈ 0.588

Similarly:

Code: python

P(Not Spam|F1, F2) = (P(F1, F2|Not Spam) * P(Not Spam)) / P(F1, F2)

= (0.06 * 0.7) / 0.102

= 0.042 / 0.102

≈ 0.412

Since P(Spam|F1, F2) > P(Not Spam|F1, F2), the email is classified as spam.

We'll explore Bayesian spam classification using the SMS Spam Collection dataset, a curated resource tailored for developing and evaluating text-based spam filters. This dataset emerges from the combined efforts of Tiago A. Almeida and Akebo Yamakami at the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Campinas in Brazil, and José María Gómez Hidalgo at the R\&D Department of Optenet in Spain.

Their work, "Contributions to the Study of SMS Spam Filtering: New Collection and Results," presented at the 2011 ACM Symposium on Document Engineering, aimed to address the growing problem of unsolicited mobile phone messages, commonly known as SMS spam. Recognizing that many existing spam filtering resources focused on email rather than text messages, the authors assembled this dataset from multiple sources, including the Grumbletext website, the NUS SMS Corpus, and Caroline Tag’s PhD thesis.

The resulting corpus contains 5,574 text messages annotated as either ham (legitimate) or spam (unwanted), making it a great resource for building and testing models that can differentiate meaningful communications from intrusive or deceptive ones. In this context, ham refers to messages from known contacts, subscriptions, or newsletters that hold value for the recipient, while spam represents unsolicited content that typically offers no benefit and may even pose risks to the user.

The first step in our process is to download this dataset, and we'll do it programmatically in our notebook.

Code: python

import requests

import zipfile

import io

# URL of the dataset

url = "https://archive.ics.uci.edu/static/public/228/sms+spam+collection.zip"

# Download the dataset

response = requests.get(url)

if response.status_code == 200:

print("Download successful")

else:

print("Failed to download the dataset")

We use the requests library to send an HTTP GET request to the URL of the dataset. We check the status code of the response to determine if the download was successful (status_code == 200).

After downloading the dataset, we need to extract its contents. The dataset is provided in a .zip file format, which we will handle using Python's zipfile and io libraries.

Code: python

# Extract the dataset

with zipfile.ZipFile(io.BytesIO(response.content)) as z:

z.extractall("sms_spam_collection")

print("Extraction successful")

Here, response.content contains the binary data of the downloaded .zip file. We use io.BytesIO to convert this binary data into a bytes-like object that can be processed by zipfile.ZipFile. The extractall method extracts all files from the archive into a specified directory, in this case, sms_spam_collection.

It's useful to verify that the extraction was successful and to see what files were extracted.

Code: python

import os

# List the extracted files

extracted_files = os.listdir("sms_spam_collection")

print("Extracted files:", extracted_files)

The os.listdir function lists all files and directories in the specified path, allowing us to confirm that the SMSSpamCollection file is present.

With the dataset extracted, we can now load it into a pandas DataFrame for further analysis. The SMS Spam Collection dataset is stored in a tab-separated values (TSV) file format, which we specify using the sep parameter in pd.read_csv.

Code: python

import pandas as pd

# Load the dataset

df = pd.read_csv(

"sms_spam_collection/SMSSpamCollection",

sep="\t",

header=None,

names=["label", "message"],

)

Here, we specify that the file is tab-separated (sep="\t"), and since the file does not contain a header row, we set header=None and provide column names manually using the names parameter.

After loading the dataset, it is important to inspect it for basic information, missing values, and duplicates. This helps ensure that the data is clean and ready for analysis.

Code: python

# Display basic information about the dataset

print("-------------------- HEAD --------------------")

print(df.head())

print("-------------------- DESCRIBE --------------------")

print(df.describe())

print("-------------------- INFO --------------------")

print(df.info())

To get an overview of the dataset, we can use the head, describe, and info methods provided by pandas.

df.head() displays the first few rows of the DataFrame, giving us a quick look at the data.df.describe() provides a statistical summary of the numerical columns in the DataFrame. Although our dataset is primarily text-based, this can still be useful for understanding the distribution of labels.df.info() gives a concise summary of the DataFrame, including the number of non-null entries and the data types of each column.Checking for missing values is crucial to ensure that our dataset does not contain any incomplete entries.

Code: python

# Check for missing values

print("Missing values:\n", df.isnull().sum())

The isnull method returns a DataFrame of the same shape as the original, with boolean values indicating whether each entry is null. The sum method then counts the number of True values in each column, giving us the total number of missing entries.

Duplicate entries can skew the results of our analysis, so it's important to identify and remove them.

Code: python

# Check for duplicates

print("Duplicate entries:", df.duplicated().sum())

# Remove duplicates if any

df = df.drop_duplicates()

The duplicated method returns a boolean Series indicating whether each row is a duplicate or not. The sum method counts the number of True values, giving us the total number of duplicate entries. We then use the drop_duplicates method to remove these duplicates from the DataFrame.

After loading the SMS Spam Collection dataset, the next step is preprocessing the text data. Preprocessing standardizes the text, reduces noise, and extracts meaningful features, all of which improve the performance of the Bayes spam classifier. The steps outlined here rely on the nltk library for tasks such as tokenization, stop word removal, and stemming.

Before processing any text, you must download the required NLTK data files. These include punkt for tokenization and stopwords for removing common words that do not contribute to meaning. Ensuring all required resources are available at this stage prevents interruptions during later processing steps.

Code: python

import nltk

# Download the necessary NLTK data files

nltk.download("punkt")

nltk.download("punkt_tab")

nltk.download("stopwords")

print("=== BEFORE ANY PREPROCESSING ===")

print(df.head(5))

Lowercasing the text ensures that the classifier treats words equally, regardless of their original casing. By converting all characters to lowercase, the model considers "Free" and "free" as the same token, effectively reducing dimensionality and improving consistency.

Code: python

# Convert all message text to lowercase

df["message"] = df["message"].str.lower()

print("\n=== AFTER LOWERCASING ===")

print(df["message"].head(5))

After this step, the dataset contains uniformly cased text, preventing the model from assigning different weights to tokens that differ only by letter case.

Removing unnecessary punctuation and numbers simplifies the dataset by focusing on meaningful words. However, certain symbols such as $ and ! may contain important context in spam messages. For example, $ might indicate a monetary amount, and ! might add emphasis.

The code below removes all characters other than lowercase letters, whitespace, dollar signs, or exclamation marks. This balance between cleaning the data and preserving important symbols helps the model concentrate on features relevant to distinguishing spam from ham messages.

Code: python

import re

# Remove non-essential punctuation and numbers, keep useful symbols like $ and !

df["message"] = df["message"].apply(lambda x: re.sub(r"[^a-z\s$!]", "", x))

print("\n=== AFTER REMOVING PUNCTUATION & NUMBERS (except $ and !) ===")

print(df["message"].head(5))

After this step, the text is cleaner, more uniform, and better suited for subsequent preprocessing tasks such as tokenization, stop word removal, or stemming.

Tokenization divides the message text into individual words or tokens, a crucial step before further analysis. By converting unstructured text into a sequence of words, we prepare the data for operations like removing stop words and applying stemming. Each token corresponds to a meaningful unit, allowing downstream processes to operate on smaller, standardized elements rather than entire sentences.

Code: python

from nltk.tokenize import word_tokenize

# Split each message into individual tokens

df["message"] = df["message"].apply(word_tokenize)

print("\n=== AFTER TOKENIZATION ===")

print(df["message"].head(5))

Once tokenized, the dataset contains messages represented as lists of words, ready for additional preprocessing steps that further refine the text data.

Stop words are common words like and, the, or is that often do not add meaningful context. Removing them reduces noise and focuses the model on the words most likely to help distinguish spam from ham messages. By reducing the number of non-informative tokens, we help the model learn more efficiently.

Code: python

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

# Define a set of English stop words and remove them from the tokens

stop_words = set(stopwords.words("english"))

df["message"] = df["message"].apply(lambda x: [word for word in x if word not in stop_words])

print("\n=== AFTER REMOVING STOP WORDS ===")

print(df["message"].head(5))

The token lists are shorter at this stage and contain fewer non-informative words, setting a cleaner stage for future text transformations.

Stemming normalizes words by reducing them to their base form (e.g., running becomes run). This consolidates different forms of the same root word, effectively cutting the vocabulary size and smoothing out the text representation. As a result, the model can better understand the underlying concepts without being distracted by trivial variations in word forms.

Code: python

from nltk.stem import PorterStemmer

# Stem each token to reduce words to their base form

stemmer = PorterStemmer()

df["message"] = df["message"].apply(lambda x: [stemmer.stem(word) for word in x])

print("\n=== AFTER STEMMING ===")

print(df["message"].head(5))

After stemming, the token lists focus on root word forms, further simplifying the text and improving the model’s generalization ability.

While tokens are useful for manipulation, many machine-learning algorithms and vectorization techniques (e.g., TF-IDF) work best with raw text strings. Rejoining the tokens into a space-separated string restores a format compatible with these methods, allowing the dataset to move seamlessly into the feature extraction phase.

Code: python

# Rejoin tokens into a single string for feature extraction

df["message"] = df["message"].apply(lambda x: " ".join(x))

print("\n=== AFTER JOINING TOKENS BACK INTO STRINGS ===")

print(df["message"].head(5))

At this point, the messages are fully preprocessed. Each message is a cleaned, normalized string ready for vectorization and subsequent model training, ultimately improving the classifier’s performance.

Feature extraction transforms preprocessed SMS messages into numerical vectors suitable for machine learning algorithms. Since models cannot directly process raw text data, they rely on numeric representations—such as counts or frequencies of words—to identify patterns that differentiate spam from ham.

A common way to represent text numerically is through a bag-of-words model. This technique constructs a vocabulary of unique terms from the dataset and represents each message as a vector of term counts. Each element in the vector corresponds to a term in the vocabulary, and its value indicates how often that term appears in the message.

Using only unigrams (individual words) does not preserve the original word order; it treats each document as a collection of terms and their frequencies, independent of sequence.

To introduce a limited sense of order, we also include bigrams, which are pairs of consecutive words. By incorporating bigrams, we capture some local ordering information.

For example, the bigram free prize might help distinguish a spam message promising a reward from a simple statement containing the word free alone. However, beyond these small sequences, the global order of words and sentence structure remains largely lost. In other words, CountVectorizer does not preserve complete word order; it only captures localized patterns defined by the chosen ngram_range.

CountVectorizer from the scikit-learn library efficiently implements the bag-of-words approach. It converts a collection of documents into a matrix of term counts, where each row represents a message and each column corresponds to a term (unigram or bigram). Before transformation, CountVectorizer applies tokenization, builds a vocabulary, and then maps each document to a numeric vector.

Key parameters for refining the feature set:

min_df=1: A term must appear in at least one document to be included. While this threshold is set to 1 here, higher values can be used in practice to exclude rare terms.max_df=0.9: Terms that appear in more than 90% of the documents are excluded, removing overly common words that provide limited differentiation.ngram_range=(1, 2): The feature matrix captures individual words and common word pairs by including unigrams and bigrams, potentially improving the model’s ability to detect spam patterns.Code: python

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

# Initialize CountVectorizer with bigrams, min_df, and max_df to focus on relevant terms

vectorizer = CountVectorizer(min_df=1, max_df=0.9, ngram_range=(1, 2))

# Fit and transform the message column

X = vectorizer.fit_transform(df["message"])

# Labels (target variable)

y = df["label"].apply(lambda x: 1 if x == "spam" else 0) # Converting labels to 1 and 0

After this step, X becomes a numerical feature matrix ready to be fed into a classifier, such as Naive Bayes.

CountVectorizer operates in three main stages:

Tokenization: Splits the text into tokens based on the specified ngram_range. For ngram_range=(1, 2), it extracts both unigrams (like "message") and bigrams (like "free prize").Building the Vocabulary: Uses min_df and max_df to decide which terms to include. Terms that are too rare or common are filtered out, leaving a vocabulary that balances informative and distinctive terms.Vectorization: Transforms each document into a vector of term counts. Each vector entry corresponds to a term from the vocabulary, and its value represents how many times that term appears in the document.Consider five documents:

The free prize is waiting for youThe spam message offers a free prize nowThe spam filter might detect thisThe important news says you won a free tripThe message truly is importantIf we use ngram_range=(1, 1) (unigrams only) and min_df=1, max_df=0.9, the word The will be removed from unigram vocabulary by max_df=0.9 since it appears more than 90% in the documents, leaving the below unigram matrix:

| Document | free | prize | is | waiting | for | you | spam | message | offers | a | now | filter | might | detect | this | important | news | says | won | trip | truly |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Using ngram_range=(1, 2), the final vocabulary includes all of the above unigrams and any valid bigrams containing those unigrams. For instance, free prize occurs in Documents 1 and 2. The resulting matrix provides additional context, helping the model differentiate messages more effectively:

| Document | free | prize | is | waiting | for | you | spam | message | offers | a | now | filter | might | detect | this | important | news | says | won | trip | truly | free prize | prize is | is waiting | waiting for | for you | spam message | message offers | offers a | a free | prize now | spam filter | filter might | might detect | detect this | important news | news says | says you | you won | won a | free trip | message truly | truly is | is important |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

This feature extraction process, using CountVectorizer, has transformed our text data into a resulting matrix provides a concise, numerical representation of each message, ready for training a classification model.

After preprocessing the text data and extracting meaningful features, we train a machine-learning model for spam detection. We use the Multinomial Naive Bayes classifier, which is well-suited for text classification tasks due to its probabilistic nature and ability to efficiently handle large, sparse feature sets.

To streamline the entire process, we employ a Pipeline. A pipeline chains together the vectorization and modeling steps, ensuring that the same data transformation (in this case, CountVectorizer) is consistently applied before feeding the transformed data into the classifier. This approach simplifies both development and maintenance by encapsulating the feature extraction and model training into a single, unified workflow.

Code: python

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split, GridSearchCV

from sklearn.naive_bayes import MultinomialNB

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

# Build the pipeline by combining vectorization and classification

pipeline = Pipeline([

("vectorizer", vectorizer),

("classifier", MultinomialNB())

])