| GTSRB | Download |

|---|---|

Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems are fundamentally data-driven. Consequently, their performance, reliability, and security are inextricably linked to the quality, integrity, and confidentiality of the data they consume and produce.

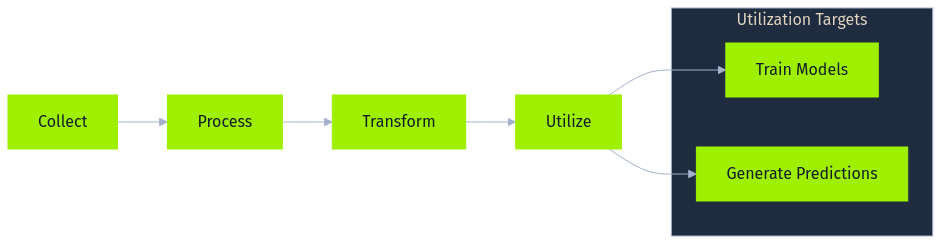

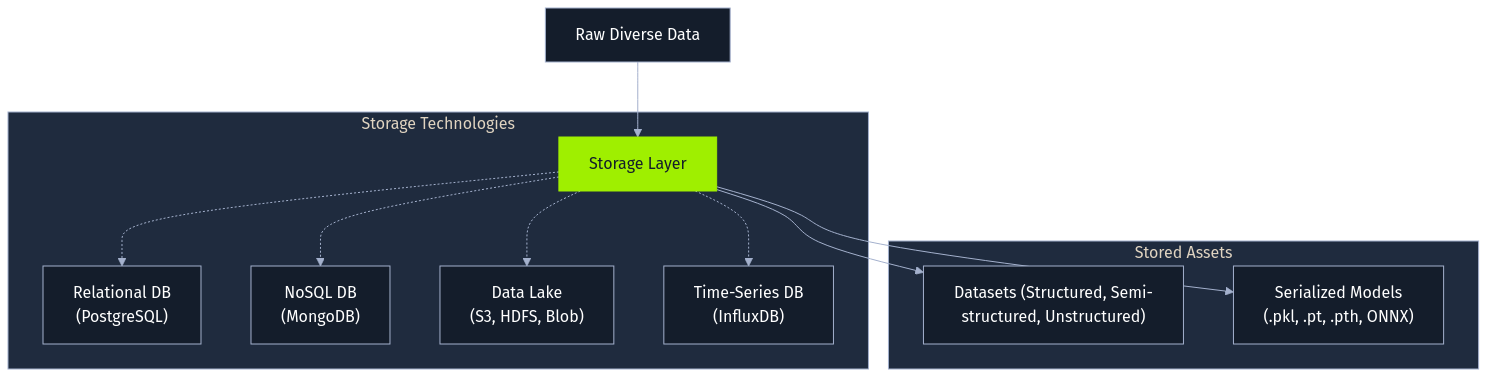

At the heart of most AI implementations lies a data pipeline, a sequence of steps designed to collect, process, transform, and ultimately utilize data for tasks such as training models or generating predictions. While the specifics vary greatly depending on the application and organization, a general data pipeline often includes several core stages, frequently leveraging specific technologies and handling diverse data formats.

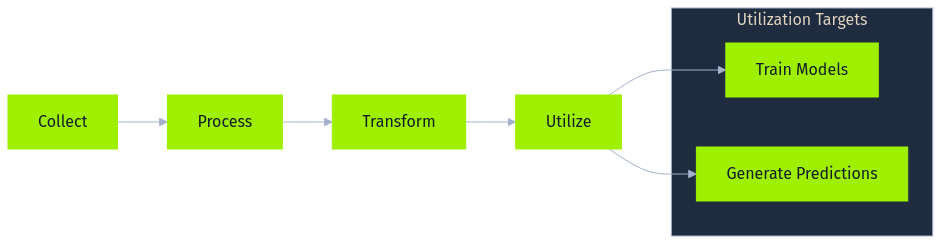

The process begins with data collection, gathering raw information from various sources. This might involve capturing user interactions from web applications as JSON logs streamed via messaging queues like Apache Kafka, ingesting structured transaction records from SQL databases like PostgreSQL, pulling sensor readings via MQTT from IoT devices, scraping public websites using tools like Scrapy, or receiving batch files (CSV, Parquet) from third parties. The collected data can range from images (JPEG) and audio (WAV) to complex semi-structured formats. The initial quality and integrity of this collected data profoundly impact all downstream processes.

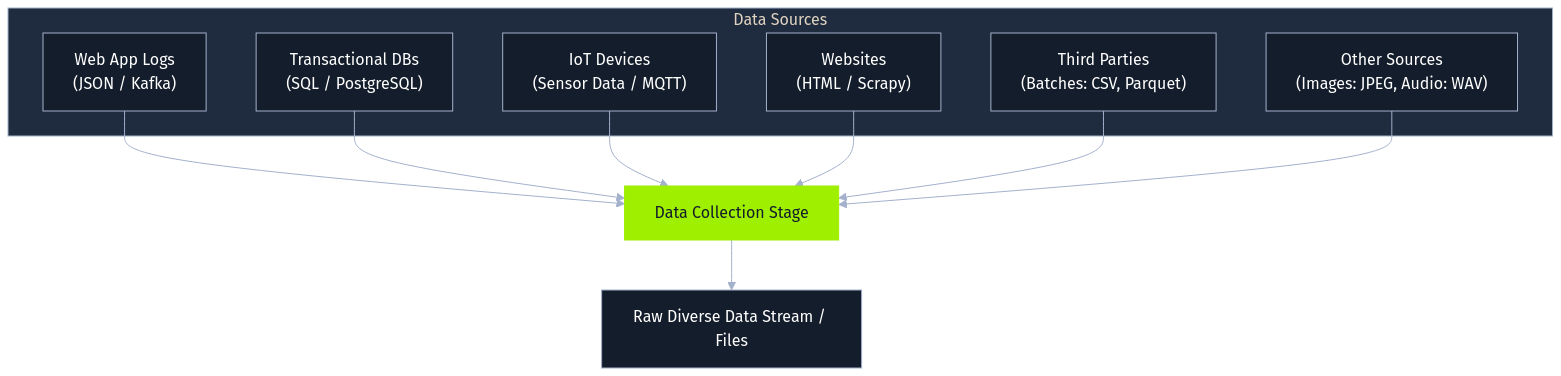

Following collection, data requires storage. The choice of technology hinges on the data's structure, volume, and access patterns. Structured data often resides in relational databases (PostgreSQL), while semi-structured logs might use NoSQL databases (MongoDB). For large, diverse datasets, organizations frequently employ data lakes built on distributed file systems (Hadoop HDFS) or cloud object storage (AWS S3, Azure Blob Storage). Specialized databases like InfluxDB cater to time-series data. Importantly, trained models themselves become stored artifacts, often serialized into formats like Python's pickle (.pkl), ONNX, or framework-specific files (.pt, .pth, .safetensors), each presenting unique security considerations if handled improperly.

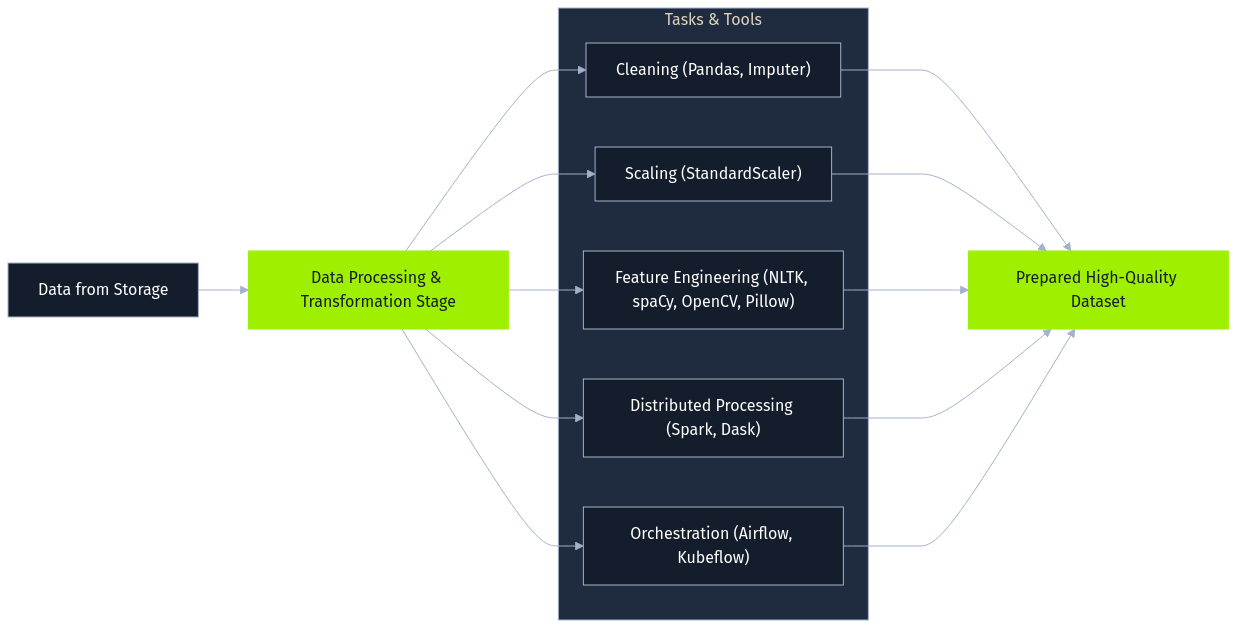

Next, raw data undergoes data processing and transformation, as it's rarely suitable for direct model use. This stage employs various libraries and frameworks for cleaning, normalization, and feature engineering. Data cleaning might involve handling missing values using Pandas and scikit-learn's Imputers. Feature scaling often uses StandardScaler or MinMaxScaler. Feature engineering creates new relevant inputs, such as extracting date components or, for text data, performing tokenization and embedding generation using NLTK or spaCy. Image data might be augmented using OpenCV or Pillow. Large datasets often necessitate distributed processing frameworks like Apache Spark or Dask, with orchestration tools like Apache Airflow or Kubeflow Pipelines managing these complex workflows. The objective is to prepare a high-quality dataset optimized for the AI task.

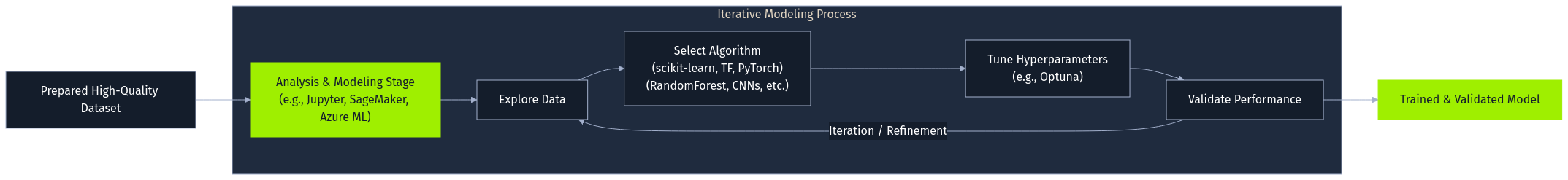

The processed data then fuels the analysis and modeling stage. Data scientists and ML engineers explore the data, often within interactive environments like Jupyter Notebooks, and train models using frameworks such as scikit-learn, TensorFlow, Jax, or PyTorch. This iterative process involves selecting algorithms (e.g., RandomForestClassifier, CNNs), tuning hyperparameters (perhaps using Optuna), and validating performance. Cloud platforms like AWS SageMaker or Azure Machine Learning often provide integrated environments for this lifecycle.

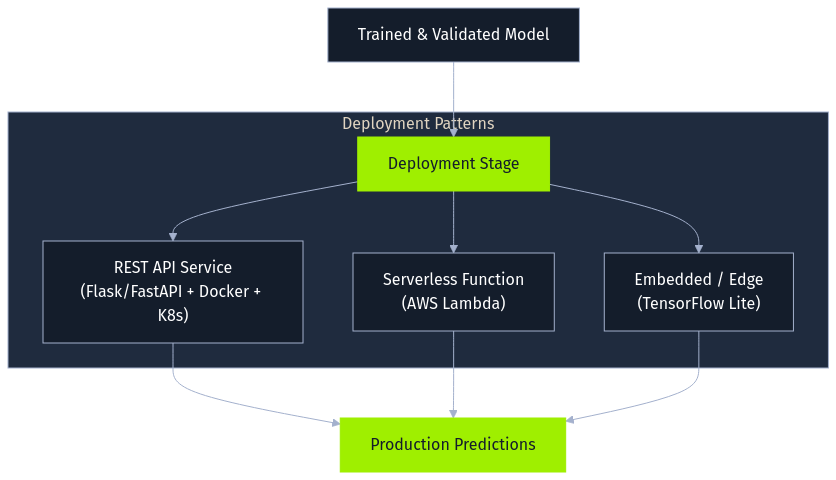

Once trained and validated, a model enters the deployment stage, where it's integrated into a production environment to serve predictions. Common patterns include exposing the model as a REST API using frameworks like Flask or FastAPI, often containerized with Docker and orchestrated by Kubernetes. Alternatively, models might become serverless functions (AWS Lambda) or be embedded directly into applications or edge devices (using formats like TensorFlow Lite). Securing the deployed model file and its surrounding infrastructure is a key concern here.

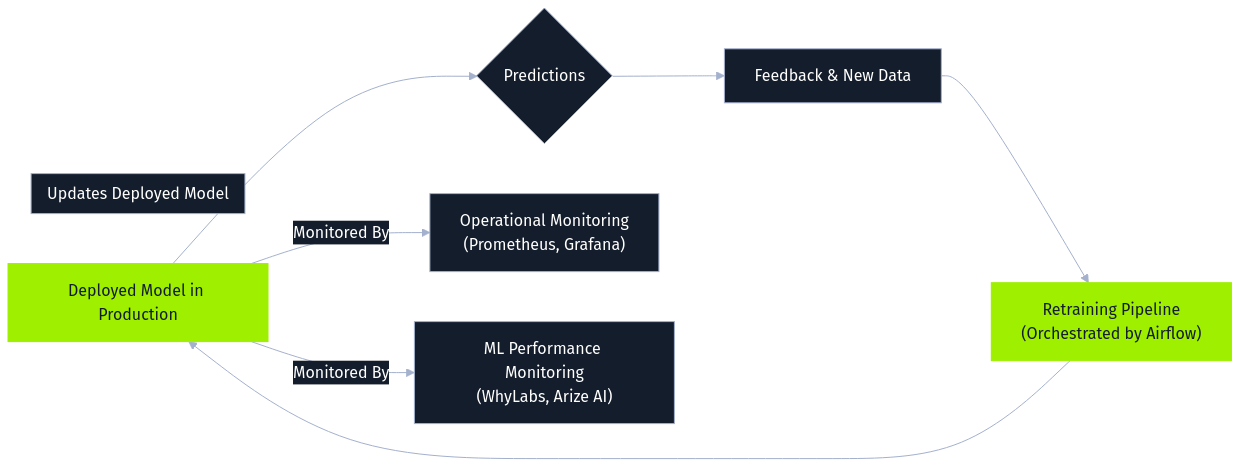

Finally, monitoring and maintenance constitute an ongoing stage. Deployed models are continuously observed for operational health using tools like Prometheus and Grafana, while specialized ML monitoring platforms (WhyLabs, Arize AI) track data drift, concept drift, and prediction quality. Feedback from predictions and user interactions is logged and often processed alongside newly collected data to periodically retrain the model. This retraining is essential for adapting to changing patterns and maintaining performance but simultaneously creates a significant attack vector. Malicious data introduced via feedback loops or ongoing collection can be incorporated during retraining, enabling online poisoning attacks. Orchestration tools like Airflow often manage these retraining pipelines, making the security of data flowing into them critical.

To clearly illustrate these complex pipelines, lets consider two examples:

First, an e-commerce platform building a product recommendation system collects user activity (JSON logs via Kafka) and reviews (text). This raw data lands in a data lake (AWS S3). Apache Spark processes this data, reconstructing sessions and performing sentiment analysis (NLTK) on reviews, outputting Parquet files. Within AWS SageMaker, a recommendation model is trained on this processed data. The resulting model file (pickle format) is stored back in S3 before being deployed via a Docker-ized Flask API on Kubernetes. Monitoring tracks click-through rates, and user feedback along with new interaction data feeds into periodic retraining cycles managed by Airflow, aiming to keep recommendations relevant but also opening the door for potential poisoning through manipulated feedback.

Second, a healthcare provider developing a predictive diagnostic tool collects anonymized patient images (DICOM) and notes (XML) from PACS and EHR systems. Secure storage (e.g., HIPAA-compliant AWS S3) is a requirement here. Python scripts using Pydicom, OpenCV, and spaCy process the data, standardizing images and extracting features. PyTorch trains a deep learning model (CNN) on specialized hardware. The validated model (.pt file) is securely stored and then deployed via an internal API to a clinical decision support system. Monitoring tracks diagnostic accuracy and data drift. While retraining might be less frequent and more rigorously controlled here, incorporating new data or corrected diagnoses still requires careful validation to prevent poisoning.

Having established the critical role of data and the structure of the data pipeline, we now focus specifically on AI data attacks. This module explores the techniques adversaries use to compromise AI systems by targeting the data itself; either during the training phase or by manipulating the stored model artifacts.

Unlike evasion attacks (manipulating inputs to fool a deployed model) or privacy attacks (extracting sensitive information from a model), the attacks covered here fundamentally undermine the model's integrity by corrupting its foundation: the data it learns from or the format it's stored in.

Each stage of the data pipeline presents potential attack surfaces adversaries can exploit.

During data collection, the primary threat is initial data poisoning, where an attacker intentionally injects malicious data. This is a prime opportunity for introducing data intended for label flipping or feature attacks. In the e-commerce example, this could manifest as submitting fake positive reviews (poisoned features/labels) to boost a product's recommendations or reviews with specific keywords (potential backdoor triggers) designed to cause unintended behavior later. For the healthcare scenario, an attacker might subtly alter DICOM metadata during ingestion or manipulate clinical notes, potentially mislabeling samples or embedding subtle feature perturbations. If this poisoned data infiltrates the training set, it can corrupt the resulting model according to the attacker's goals.

The storage stage faces traditional data security threats alongside model-specific risks, particularly relevant for model stenography and Trojan attacks. Unauthorized access to the AWS S3 data lake or the healthcare provider's secure storage could allow theft or tampering of training datasets, potentially modifying labels or features post-collection. Furthermore, stored model files (the .pkl recommendation model on S3, the .pt diagnostic model) are valuable targets. An attacker gaining write access could replace a legitimate model with a malicious one containing an embedded trojan or execute a model stenography attack by hiding code within the model file itself (leveraging insecure deserialization like pickle.load()), potentially compromising the Flask API server or the clinical system upon loading.

Data processing offers another avenue for manipulation, potentially facilitating label flipping or feature attacks even on initially clean data. If an attacker influences the cleaning, transformation, or feature engineering steps, they can corrupt data before modeling. Compromising the e-commerce platform's Spark job could lead to mislabeled review sentiments (label flipping), while manipulating the healthcare provider's Python scripts could introduce subtle errors into standardized images or extracted text features (feature attacks), impacting the downstream model.

The analysis and modeling stage is where the impact of data poisoning attacks introduced earlier becomes concrete. When the AWS SageMaker job trains the recommendation model on poisoned Parquet files containing flipped labels or perturbed features, or the PyTorch process trains the diagnostic CNN on data embedded with backdoor triggers, the resulting model learns the attacker's desired manipulations. It might learn incorrect patterns, exhibit biases, or contain hidden backdoors activated by specific inputs later.

During deployment, the integrity of the model artifact remains crucial, especially concerning Trojan and model stenography risks. If the mechanism loading the model from storage (S3, secure file system) into the production environment is insecure, an attacker could inject a malicious model file at this point, achieving the same trojan effect or code execution via stenography as compromising the storage layer directly.

Finally, the monitoring and maintenance stage, especially the common practice of retraining models, acts as a critical enabler for training data attacks like online poisoning. For example, the e-commerce platform's Airflow retraining pipeline is a prime target. Attackers could continuously submit manipulated data: perhaps subtly altering clickstream data (feature attacks), submitting misleading feedback to influence future labels (label flipping), or injecting data designed to skew model weights towards particular outcomes over time. This gradual corruption degrades recommendation quality or introduces biases without needing initial dataset access.

The impact of successful AI data attacks can be severe, ranging from subtly biased decision-making and degraded system performance to complete model compromise and potentially enabling broader system breaches through embedded trojans.

Leading security frameworks such as the OWASP Top 10 for LLM Applications, as highlighted in the "Introduction to Red Teaming AI" module, provides specific context for risks within the AI pipeline.

The major risk we are particularly focused on is Data poisoning, where attackers manipulate data during collection, processing, training, or feedback stages. This directly corresponds to OWASP LLM03: Training Data Poisoning.

Another relevant category of risk is the AI Supply Chain, addressed by OWASP LLM05: Supply Chain Vulnerabilities. This encompasses several related threats: compromising the integrity of third-party data sources, tampering with pre-trained model artifacts (like injecting trojans), or exploiting vulnerabilities in the software components and platforms that make up the pipeline infrastructure itself. While LLM05 covers many infrastructure aspects tied to components, robust protection also demands adherence to general secure system design principles beyond specific LLM list items, preventing unauthorized access throughout the pipeline. Ultimately, recognizing how both Training Data Poisoning and Supply Chain Vulnerabilities manifest is key to understanding the vulnerabilities in the AI data and model lifecycle

Complementing OWASP's specific vulnerability focus, Google's Secure AI Framework (SAIF) provides a broader, lifecycle-oriented perspective. The data integrity issues identified map well onto SAIF's core elements.

For instance, SAIF’s principles regarding Secure Design, securing Data components, and managing the Secure Supply Chain directly address the need to protect data throughout its lifecycle. Preventing Data Poisoning aligns with securing this Data Supply Chain and implementing rigorous Security Testing and validation during Model development, especially for data used in retraining. Likewise, maintaining model artifact integrity and preventing malicious code injection are central to SAIF’s Secure Deployment practices and verifying the Secure Supply Chain.

Finally, the challenge of monitoring for data or model manipulation, particularly within dynamic retraining loops, is covered by SAIF's emphasis on Secure Monitoring & Response.

Label Flipping is arguably the simplest form of a data poisoning attack. It directly targets the ground truth information used during model training.

The idea behind the attack is straightforward: an adversary gains access to a portion of the training dataset and deliberately changes the assigned labels (the correct answers or categories) for some data points. The actual features of the data points remain untouched; only their associated class designation is altered.

For example, in a dataset used to classify images, an image originally labeled as cat might have its label flipped to dog. In a dataset used to train a spam classifier, an email labeled as spam might be relabeled as not spam.

The most common goal of an attacker executing a Label Flipping attack is to degrade model performance. By introducing incorrect labels, the attack forces the model to learn incorrect associations between features and classes, resulting in a "confused" model that has a general decrease in performance (eg accuracy, precision, recall, etc).

The adversary doesn't necessarily care which specific inputs are misclassified, only that the model becomes less reliable and useful overall, but even such a simple attack can have devastating consequences.

This attack directly embodies the risks outlined under OWASP LLM03: Training Data Poisoning. The adversary might not aim for specific misclassifications but rather seeks to undermine the model's overall reliability and utility. Even this relatively simple attack can have significant negative consequences.

This type of attack often targets data after it has been collected, focusing on compromising the integrity of datasets held within the Storage stage of the pipeline. For example, an attacker might gain unauthorized access to modify label columns in CSV files stored in a data lake (like AWS S3) or manipulate records in a PostgreSQL database. Label flipping could also occur if Data Processing scripts are compromised and alter labels during transformation.

Let's consider hypothetical example: A company is training an AI model to analyze customer feedback on a newly launched products, labeling each review as positive or negative. An attacker targets this process. Gaining access to the training dataset, they randomly flip the labels on a portion of these reviews - marking some genuinely positive feedback as negative, and vice-versa.

The immediate goal is straightforward: to degrade the accuracy of the final sentiment analysis model.

The effect on the company however, is more damaging. The model, now trained on this poisoned data, becomes unreliable and unpredictable. For instance, it might incorrectly report that the overall customer sentiment towards the new product is predominantly negative, even if the actual feedback is largely positive, or it might report negative reviews as positive.

Relying on this faulty analysis, the company might make incorrect decisions - perhaps they prematurely pull the product from the market, invest heavily in 'fixing' features customers actually liked, or miss crucial positive signals indicating success, leading to potentially crippling the business.

To demonstrate how such an attack would work, we will build a model around the sentiment analysis scenario. A company is training a model to classify customer feedback as positive or negative, and we, as the adversary, will attack the training dataset by flipping labels.

First we need to setup the environment.

Code: python

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import make_blobs

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, classification_report, confusion_matrix

import seaborn as sns

htb_green = "#9fef00"

node_black = "#141d2b"

hacker_grey = "#a4b1cd"

white = "#ffffff"

azure = "#0086ff"

nugget_yellow = "#ffaf00"

malware_red = "#ff3e3e"

vivid_purple = "#9f00ff"

aquamarine = "#2ee7b6"

# Configure plot styles

plt.style.use("seaborn-v0_8-darkgrid")

plt.rcParams.update(

{

"figure.facecolor": node_black,

"axes.facecolor": node_black,

"axes.edgecolor": hacker_grey,

"axes.labelcolor": white,

"text.color": white,

"xtick.color": hacker_grey,

"ytick.color": hacker_grey,

"grid.color": hacker_grey,

"grid.alpha": 0.1,

"legend.facecolor": node_black,

"legend.edgecolor": hacker_grey,

"legend.frameon": True,

"legend.framealpha": 1.0,

"legend.labelcolor": white,

}

)

# Seed for reproducibility

SEED = 1337

np.random.seed(SEED)

print("Setup complete. Libraries imported and styles configured.")

We need data representing the customer reviews. Since processing real text data is complex and outside the scope of demonstrating the attack mechanism itself, we'll use Scikit-Learn's make_blobs function to create a synthetic dataset. This provides a simplified, two-dimensional representation suitable for binary classification and visualization.

Imagine that these two dimensions (Sentiment Feature 1, Sentiment Feature 2) are numerical features derived from the text reviews through some preprocessing step (e.g., using techniques like TF-IDF or word embeddings, then potentially dimensionality reduction).

We'll generate isotropic Gaussian blobs, essentially clusters of points in this 2D feature space.

Each point 𝐱i=(xi1,xi2) represents a review instance with its two derived features, and each instance is assigned a label yi.

One cluster will represent Class 0 (simulating Negative sentiment) and the other Class 1 (simulating Positive sentiment). This synthetic dataset is designed to be reasonably separable, making it easier to visualize the impact of the label flipping attack on the model's decision boundary.

Code: python

# Generate synthetic data

n_samples = 1000

centers = [(0, 5), (5, 0)] # Define centers for two distinct blobs

X, y = make_blobs(

n_samples=n_samples,

centers=centers,

n_features=2,

cluster_std=1.25,

random_state=SEED,

)

# Split data into training and testing sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=SEED

)

print(f"Generated {n_samples} samples.")

print(f"Training set size: {X_train.shape[0]} samples.")

print(f"Testing set size: {X_test.shape[0]} samples.")

print(f"Number of features: {X_train.shape[1]}")

print(f"Classes: {np.unique(y)}")

Let's plot the clean dataset so it's very easy to see the relations in the data.

Code: python

def plot_data(X, y, title="Dataset Visualization"):

"""

Plots the 2D dataset with class-specific colors.

Parameters:

- X (np.ndarray): Feature data (n_samples, 2).

- y (np.ndarray): Labels (n_samples,).

- title (str): The title for the plot.

"""

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

scatter = plt.scatter(

X[:, 0],

X[:, 1],

c=y,

cmap=plt.cm.colors.ListedColormap([azure, nugget_yellow]),

edgecolors=node_black,

s=50,

alpha=0.8,

)

plt.title(title, fontsize=16, color=htb_green)

plt.xlabel("Sentiment Feature 1", fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel("Sentiment Feature 2", fontsize=12)

# Create a legend

handles = [

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="o",

color="w",

label="Negative Sentiment (Class 0)",

markersize=10,

markerfacecolor=azure,

),

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="o",

color="w",

label="Positive Sentiment (Class 1)",

markersize=10,

markerfacecolor=nugget_yellow,

),

]

plt.legend(handles=handles, title="Sentiment Classes")

plt.grid(True, color=hacker_grey, linestyle="--", linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.3)

plt.show()

# Plot the data

plot_data(X_train, y_train, title="Original Training Data Distribution")

This shows the two distinct classes we aim to classify.

Before executing the attack, we need to establish baseline performance so we have something to compare the effects of the poisoned model with. We will train a Logistic Regression model on the original, clean training data (X_train, y_train). This baseline represents the model's expected behavior and accuracy under normal, non-adversarial conditions.

As outlined in the "Fundamentals of AI" module, Logistic Regression is fundamentally a classification algorithm used for predicting binary outcomes.

For a given review represented by its feature vector 𝐱i=(xi1,xi2), the model first calculates a linear combination zi using weights 𝐰=(w1,w2) and a bias term b:

zi=𝐰T𝐱i+b=w1xi1+w2xi2+b

This value zi represents the log-odds (or logit) of the review having positive sentiment (yi=1). It quantifies the linear relationship between the derived features and the log-odds of a positive classification.

zi=log(P(yi=1|𝐱i)1−P(yi=1|𝐱i))

To convert the log-odds zi into a probability pi=P(yi=1|𝐱i) (the probability of the review being positive), the model applies the sigmoid function, σ:

pi=σ(zi)=11+e−zi=11+e−(𝐰T𝐱i+b)

The sigmoid function squashes the output zi into the range [0,1], representing the model’s estimated probability that the review 𝐱i has positive sentiment.

During training, the model learns the optimal parameters 𝐰 and b by minimizing a loss function over the training set (X_train, y_train). The goal is to find parameters that make the predicted probabilities pi as close as possible to the true sentiment labels yi. The standard loss function for binary classification is the binary cross-entropy or log-loss:

L(𝐰,b)=−1N∑i=1N[yilog(pi)+(1−yi)log(1−pi)]

Here, N is the number of training reviews, yi is the true sentiment label (0 or 1) for the i-th review, and pi is the model’s predicted probability of positive sentiment for that review. Optimization algorithms like gradient descent iteratively adjust 𝐰 and b to minimize this loss L.

Once trained, the model uses the learned 𝐰 and b to predict the sentiment of new, unseen reviews. For a new review 𝐱, it calculates the probability p=σ(𝐰T𝐱+b). Typically, if p≥0.5, the review is classified as positive (Class 1); otherwise, it’s classified as negative (Class 0).

The decision boundary is the line (in our 2D feature space) where the model is exactly uncertain (p=0.5), which occurs when z=𝐰T𝐱+b=0. This linear boundary separates the feature space into regions predicted as negative and positive sentiment. The training process finds the line that best separates the clusters in the training data.

We now train this baseline model on our clean data and evaluate its accuracy on the unseen test set.

Code: python

# Initialize and train the Logistic Regression model

baseline_model = LogisticRegression(random_state=SEED)

baseline_model.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Predict on the test set

y_pred_baseline = baseline_model.predict(X_test)

# Calculate baseline accuracy

baseline_accuracy = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred_baseline)

print(f"Baseline Model Accuracy: {baseline_accuracy:.4f}")

# Prepare to plot the decision boundary

def plot_decision_boundary(model, X, y, title="Decision Boundary"):

"""

Plots the decision boundary of a trained classifier on a 2D dataset.

Parameters:

- model: The trained classifier object (must have a .predict method).

- X (np.ndarray): Feature data (n_samples, 2).

- y (np.ndarray): Labels (n_samples,).

- title (str): The title for the plot.

"""

h = 0.02 # Step size in the mesh

x_min, x_max = X[:, 0].min() - 1, X[:, 0].max() + 1

y_min, y_max = X[:, 1].min() - 1, X[:, 1].max() + 1

xx, yy = np.meshgrid(np.arange(x_min, x_max, h), np.arange(y_min, y_max, h))

# Predict the class for each point in the mesh

Z = model.predict(np.c_[xx.ravel(), yy.ravel()])

Z = Z.reshape(xx.shape)

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

# Plot the decision boundary contour

plt.contourf(

xx, yy, Z, cmap=plt.cm.colors.ListedColormap([azure, nugget_yellow]), alpha=0.3

)

# Plot the data points

scatter = plt.scatter(

X[:, 0],

X[:, 1],

c=y,

cmap=plt.cm.colors.ListedColormap([azure, nugget_yellow]),

edgecolors=node_black,

s=50,

alpha=0.8,

)

plt.title(title, fontsize=16, color=htb_green)

plt.xlabel("Feature 1", fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel("Feature 2", fontsize=12)

# Create a legend manually

handles = [

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="o",

color="w",

label="Negative Sentiment (Class 0)",

markersize=10,

markerfacecolor=azure,

),

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="o",

color="w",

label="Positive Sentiment (Class 1)",

markersize=10,

markerfacecolor=nugget_yellow,

),

]

plt.legend(handles=handles, title="Classes")

plt.grid(True, color=hacker_grey, linestyle="--", linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.3)

plt.xlim(xx.min(), xx.max())

plt.ylim(yy.min(), yy.max())

plt.show()

# Plot the decision boundary for the baseline model

plot_decision_boundary(

baseline_model,

X_train,

y_train,

title=f"Baseline Model Decision Boundary\nAccuracy: {baseline_accuracy:.4f}",

)

The resulting plot shows the linear decision boundary learned by the baseline model, effectively separating the simulated Negative and Positive sentiment clusters in the training data. The high accuracy score indicates it generalizes well to the unseen test data.

With an established baseline, we can now execute the actual attack, and to do this, we will create a function that will take the original training labels (y_train, representing the true sentiments) and a poisoning percentage as input. It will randomly select the specified fraction of training data points (reviews) and flip their labels - changing Negative (0) to Positive (1) and Positive (1) to Negative (0).

The implication of this is significant. As we have established, the model learns its parameters (𝐰,b) by minimizing the average log-loss, L, across the training dataset, the whole point of training is to find the 𝐰 and b that make this loss L as small as possible, meaning the predicted probabilities pi align well with the true labels yi.

When we flip a label for a specific instance from its true value yi to an incorrect value yi′, we directly corrupt the contribution of that instance to the overall loss calculation. For example, consider an instance 𝐱i that truly belongs to class 0 (so yi=0) but its label is flipped to yi′=1. The term for this instance inside the sum changes from −[0⋅log(pi)+(1−0)log(1−pi)]=−log(1−pi) to −[1⋅log(pi)+(1−1)log(1−pi)]=−log(pi).

If the model, based on the features 𝐱i, correctly learns to predict a low probability pi for class 1 (since the instance truly belongs to class 0), the original term −log(1−pi) would be small, but the corrupted term −log(pi) becomes very large as pi→0.

This large error signal for the flipped instance strongly influences the optimization process. It forces the algorithm to adjust the parameters 𝐰 and b not only fit the correctly labeled data, but also to try and accommodate these poisoned points, and in doing so, it pushes the learned decision boundary defined by 𝐰T𝐱+b=0, away from the optimal position determined by the true underlying data distribution.

To execute this attack, we will implement a function to contain all logic: flip_labels. This function takes the original training labels (y_train) and a poison_percentage as input, specifying the fraction of labels to flip.

First, we define the function signature and ensure the provided poison_percentage is a valid value between 0 and 1. This prevents nonsensical inputs. We also calculate the absolute number of labels to flip (n_to_flip) based on the total number of samples and the specified percentage.

Code: python

def flip_labels(y, poison_percentage):

if not 0 <= poison_percentage <= 1:

raise ValueError("poison_percentage must be between 0 and 1.")

n_samples = len(y)

n_to_flip = int(n_samples * poison_percentage)

if n_to_flip == 0:

print("Warning: Poison percentage is 0 or too low to flip any labels.")

# Return unchanged labels and empty indices if no flips are needed

return y.copy(), np.array([], dtype=int)

Next, we select which specific reviews (data points) will have their sentiment labels flipped. We use a NumPy random number generator (rng_instance) seeded with our global SEED (or the function's seed parameter) for reproducible random selection. The choice method selects n_to_flip unique indices from the range 0 to n_samples - 1 without replacement. These flipped_indices identify the exact reviews targeted by the attack.

Code: python

# Use the defined SEED for the random number generator

rng_instance = np.random.default_rng(SEED)

# Select unique indices to flip

flipped_indices = rng_instance.choice(n_samples, size=n_to_flip, replace=False)

Now, we perform the actual label flipping. We create a copy of the original label array (y_poisoned = y.copy()) to avoid altering the original data. For the elements at the flipped_indices, we invert their labels: 0 becomes 1, and 1 becomes 0. A concise way to do this is 1 - label for binary 0/1 labels, or using np.where for clarity.

Code: python

# Create a copy to avoid modifying the original array

y_poisoned = y.copy()

# Get the original labels at the indices we are about to flip

original_labels_at_flipped = y_poisoned[flipped_indices]

# Apply the flip: if original was 0, set to 1; otherwise (if 1), set to 0

y_poisoned[flipped_indices] = np.where(original_labels_at_flipped == 0, 1, 0)

print(f"Flipping {n_to_flip} labels ({poison_percentage * 100:.1f}%).")

Lastly, the function returns the y_poisoned array containing the corrupted labels and the flipped_indices array, allowing us to track which reviews were affected.

Code: python

return y_poisoned, flipped_indices

We also need a function to plot the data so its easy to see the effects of the attack.

Code: python

def plot_poisoned_data(

X,

y_original,

y_poisoned,

flipped_indices,

title="Poisoned Data Visualization",

target_class_info=None,

):

"""

Plots a 2D dataset, highlighting points whose labels were flipped.

Parameters:

- X (np.ndarray): Feature data (n_samples, 2).

- y_original (np.ndarray): The original labels before flipping (used for context if needed, currently unused in logic but good practice).

- y_poisoned (np.ndarray): Labels after flipping.

- flipped_indices (np.ndarray): Indices of the samples that were flipped.

- title (str): The title for the plot.

- target_class_info (int, optional): The class label of the points that were targeted for flipping. Defaults to None.

"""

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 7))

# Identify non-flipped points

mask_not_flipped = np.ones(len(y_poisoned), dtype=bool)

mask_not_flipped[flipped_indices] = False

# Plot non-flipped points (color by their poisoned label, which is same as original)

plt.scatter(

X[mask_not_flipped, 0],

X[mask_not_flipped, 1],

c=y_poisoned[mask_not_flipped],

cmap=plt.cm.colors.ListedColormap([azure, nugget_yellow]),

edgecolors=node_black,

s=50,

alpha=0.6,

label="Unchanged Label", # Keep this generic

)

# Determine the label for flipped points in the legend

if target_class_info is not None:

flipped_legend_label = f"Flipped (Orig Class {target_class_info})"

# You could potentially use target_class_info to adjust facecolor if needed,

# but current logic colors by the new label which is often clearer.

else:

flipped_legend_label = "Flipped Label"

# Plot flipped points with a distinct marker and outline

if len(flipped_indices) > 0:

# Color flipped points according to their new (poisoned) label

plt.scatter(

X[flipped_indices, 0],

X[flipped_indices, 1],

c=y_poisoned[flipped_indices], # Color by the new label

cmap=plt.cm.colors.ListedColormap([azure, nugget_yellow]),

edgecolors=malware_red, # Highlight edge in red

linewidths=1.5,

marker="X", # Use 'X' marker

s=100,

alpha=0.9,

label=flipped_legend_label, # Use the determined label

)

plt.title(title, fontsize=16, color=htb_green)

plt.xlabel("Feature 1", fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel("Feature 2", fontsize=12)

# Create legend

handles = [

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="o",

color="w",

label="Class 0 Point (Azure)",

markersize=10,

markerfacecolor=azure,

linestyle="None",

),

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="o",

color="w",

label="Class 1 Point (Yellow)",

markersize=10,

markerfacecolor=nugget_yellow,

linestyle="None",

),

# Add the flipped legend entry using the label

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="X",

color="w",

label=flipped_legend_label,

markersize=12,

markeredgecolor=malware_red,

markerfacecolor=hacker_grey,

linestyle="None",

),

]

plt.legend(handles=handles, title="Data Points")

plt.grid(True, color=hacker_grey, linestyle="--", linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.3)

plt.show()

Let's begin by poisoning a small fraction, say 10%, of the training labels and observe the impact on our sentiment analysis model.

The process involves several steps:

flip_labels function on the original y_train data to create a poisoned version (y_train_poisoned_10) where 10% of the sentiment labels are flipped.plot_poisoned_data to see which points were flipped.Logistic Regression model (model_10_percent) using the original features X_train but the poisoned labels y_train_poisoned_10.X_test, y_test). This is crucial - we want to see how the poisoning affects performance on legitimate, unseen data.model_10_percent using plot_decision_boundary.Code: python

results = {

"percentage": [],

"accuracy": [],

"model": [],

"y_train_poisoned": [],

"flipped_indices": [],

}

decision_boundaries_data = [] # To store data for the combined plot

# Add baseline results first

results["percentage"].append(0.0)

results["accuracy"].append(baseline_accuracy)

results["model"].append(baseline_model)

results["y_train_poisoned"].append(y_train.copy())

results["flipped_indices"].append(np.array([], dtype=int))

# Calculate meshgrid once for all boundary plots

h = 0.02 # Step size in the mesh

x_min, x_max = X_train[:, 0].min() - 1, X_train[:, 0].max() + 1

y_min, y_max = X_train[:, 1].min() - 1, X_train[:, 1].max() + 1

xx, yy = np.meshgrid(np.arange(x_min, x_max, h), np.arange(y_min, y_max, h))

mesh_points = np.c_[xx.ravel(), yy.ravel()]

# Perform 10% Poisoning

poison_percentage_10 = 0.10

print(f"\n--- Testing with {poison_percentage_10 * 100:.0f}% Poisoned Data ---")

# Create 10% Poisoned Data

y_train_poisoned_10, flipped_indices_10 = flip_labels(y_train, poison_percentage_10)

# Visualize 10% Poisoned Data

plot_poisoned_data(

X_train,

y_train,

y_train_poisoned_10,

flipped_indices_10,

title=f"Training Data with {poison_percentage_10 * 100:.0f}% Flipped Labels",

)

# Train Model on 10% Poisoned Data

model_10_percent = LogisticRegression(random_state=SEED)

model_10_percent.fit(X_train, y_train_poisoned_10) # Train with original X, poisoned y

# Evaluate on Clean Test Data

y_pred_10_percent = model_10_percent.predict(X_test)

accuracy_10_percent = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred_10_percent)

print(f"Accuracy on clean test set (10% poisoned): {accuracy_10_percent:.4f}")

# Store Results

results["percentage"].append(poison_percentage_10)

results["accuracy"].append(accuracy_10_percent)

results["model"].append(model_10_percent)

results["y_train_poisoned"].append(y_train_poisoned_10)

results["flipped_indices"].append(flipped_indices_10)

# Visualize Decision Boundary

plot_decision_boundary(

model_10_percent,

X_train,

y_train_poisoned_10, # Visualize boundary with poisoned labels shown

title=f"Decision Boundary ({poison_percentage_10 * 100:.0f}% Poisoned)\nAccuracy: {accuracy_10_percent:.4f}",

)

# Store decision boundary prediction for combined plot

Z_10 = model_10_percent.predict(mesh_points)

Z_10 = Z_10.reshape(xx.shape)

decision_boundaries_data.append({"percentage": poison_percentage_10, "Z": Z_10})

print(

f"Baseline accuracy was: {baseline_accuracy:.4f}"

) # Print baseline for comparison

In this specific case, with our clearly separated synthetic data, poisoning only 10% of the labels results in no accuracy loss, both are 99.33% accurate. While the accuracy has not changed, the decision boundary will still have shifted slightly as the model compensates for the poisoned data.

To get a clearer view of the shift, let's overlay the original baseline boundary (trained on clean data) and the 10% poisoned boundary on the same plot.

Code: python

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

# Plot the 10% poisoned data points for context

mask_not_flipped_10 = np.ones(len(y_train), dtype=bool)

mask_not_flipped_10[flipped_indices_10] = False

plt.scatter(

X_train[mask_not_flipped_10, 0],

X_train[mask_not_flipped_10, 1],

c=y_train_poisoned_10[mask_not_flipped_10],

cmap=plt.cm.colors.ListedColormap([azure, nugget_yellow]),

edgecolors=node_black,

s=50,

alpha=0.6,

label="Original Label (in 10% set)",

)

# Plot flipped points ('X' marker)

if len(flipped_indices_10) > 0:

plt.scatter(

X_train[flipped_indices_10, 0],

X_train[flipped_indices_10, 1],

c=y_train_poisoned_10[flipped_indices_10], # Color by the new poisoned label

cmap=plt.cm.colors.ListedColormap([azure, nugget_yellow]),

edgecolors=malware_red,

linewidths=1.5,

marker="X",

s=100,

alpha=0.9,

label="Flipped Label (10% set)",

)

# Overlay Baseline Decision Boundary (Solid Green)

baseline_model_retrieved = results["model"][

results["percentage"].index(0.0)

] # Get baseline model

if baseline_model_retrieved:

Z_baseline = baseline_model_retrieved.predict(mesh_points).reshape(xx.shape)

plt.contour(

xx,

yy,

Z_baseline,

levels=[0.5],

colors=[htb_green],

linestyles=["solid"],

linewidths=[2.5],

)

else:

print("Warning: Baseline model not found for comparison plot.")

# Overlay 10% Poisoned Decision Boundary

plt.contour(

xx,

yy,

Z_10,

levels=[0.5],

colors=[aquamarine],

linestyles=["dashed"],

linewidths=[2.5],

)

plt.title(

"Comparison: Baseline vs. 10% Poisoned Decision Boundary",

fontsize=16,

color=htb_green,

)

plt.xlabel("Feature 1", fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel("Feature 2", fontsize=12)

# Create legend

handles = [

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

color=htb_green,

lw=2.5,

linestyle="solid",

label="Baseline Boundary (0%)",

),

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

color=aquamarine,

lw=2.5,

linestyle="dashed",

label="Poisoned Boundary (10%)",

),

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="o",

color="w",

label="Class 0 Point",

markersize=10,

markerfacecolor=azure,

linestyle="None",

),

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="o",

color="w",

label="Class 1 Point",

markersize=10,

markerfacecolor=nugget_yellow,

linestyle="None",

),

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="X",

color="w",

label="Flipped Point",

markersize=10,

markeredgecolor=malware_red,

markerfacecolor=hacker_grey,

linestyle="None",

),

]

plt.legend(handles=handles, title="Boundaries & Data Points")

plt.grid(True, color=hacker_grey, linestyle="--", linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.3)

plt.xlim(xx.min(), xx.max())

plt.ylim(yy.min(), yy.max())

plt.show()

We can clearly see how the decision boundary has started to shift in this plot:

Now, let's systematically increase the poisoning percentage from 20% up to 50% and observe the effects. We will repeat the process for each level: flip labels, train a new model, evaluate its accuracy on the clean test set, and visualize the resulting decision boundary.

Code: python

poison_percentages_high = [0.20, 0.30, 0.40, 0.50]

for pp in poison_percentages_high:

print(f"\n--- Training with {pp * 100:.0f}% Poisoned Data ---")

# Create Poisoned Data

y_train_poisoned, flipped_idx = flip_labels(y_train, pp)

# Train Model on Poisoned Data

poisoned_model = LogisticRegression(random_state=SEED)

try:

poisoned_model.fit(

X_train, y_train_poisoned

) # Train with original X, but poisoned y

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error training model at {pp * 100}% poisoning: {e}")

results["percentage"].append(pp)

results["accuracy"].append(np.nan) # Indicate failure

results["model"].append(None)

results["y_train_poisoned"].append(

y_train_poisoned

) # Still store poisoned labels

results["flipped_indices"].append(flipped_idx) # and indices

continue # Skip to next percentage

# Evaluate on Clean Test Data

y_pred_poisoned = poisoned_model.predict(X_test)

accuracy = accuracy_score(

y_test, y_pred_poisoned

) # Always evaluate against TRUE test labels

print(f"Accuracy on clean test set: {accuracy:.4f}")

# Store Results

results["percentage"].append(pp)

results["accuracy"].append(accuracy)

results["model"].append(poisoned_model)

results["y_train_poisoned"].append(y_train_poisoned)

results["flipped_indices"].append(flipped_idx)

# Visualize Poisoned Data and Decision Boundary

plot_poisoned_data(

X_train,

y_train,

y_train_poisoned,

flipped_idx,

title=f"Training Data with {pp * 100:.0f}% Flipped Labels",

)

plot_decision_boundary(

poisoned_model,

X_train,

y_train_poisoned, # Visualize boundary with poisoned labels shown

title=f"Decision Boundary ({pp * 100:.0f}% Poisoned)\nAccuracy: {accuracy:.4f}",

)

# Store decision boundary prediction for combined plot

Z = poisoned_model.predict(mesh_points)

Z = Z.reshape(xx.shape)

decision_boundaries_data.append({"percentage": pp, "Z": Z})

print("\n--- Evaluation Complete for Higher Percentages ---")

Looking at the outputs we can see how the boundaries are shifting for each percentage shift.

Let's consolidate the findings. We'll first plot the trend of the model's accuracy (evaluated on the clean test set) against the percentage of labels flipped during training (from 0% up to 50%).

Code: python

# Plot accuracy vs. poisoning percentage

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 5))

# Ensure percentages and accuracies are sorted correctly if the order changed for any reason

plot_data = sorted(zip(results["percentage"], results["accuracy"]))

plot_percentages = [p * 100 for p, a in plot_data]

plot_accuracies = [a for p, a in plot_data]

plt.plot(

plot_percentages,

plot_accuracies,

marker="o",

linestyle="-",

color=htb_green,

markersize=8,

)

plt.title("Model Accuracy vs. Label Flipping Percentage", fontsize=16, color=htb_green)

plt.xlabel("Percentage of Training Labels Flipped (%)", fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel("Accuracy on Clean Test Set", fontsize=12)

plt.xticks(plot_percentages) # Ensure ticks match the evaluated percentages

plt.ylim(0, 1.05)

plt.grid(True, color=hacker_grey, linestyle="--", linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.3)

plt.show()

Because our data is so clearly separated, the shifting boundaries don't actually cause any significant accuracy loss. Remember, this is only the case for our limited data, in a real world attack, where data is far from being clean or clear, it's quite probable that even a slight shift in the boundary will cause an accuracy loss.

Despite this no significant loss in accuracy until 50% of the data is poisoned, the decison boundary will still be constantly shifting. We can plot all of the boundaries overlaid into a single image to clearly visualize this phenomenon.

Code: python

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

# Plot the original clean data points for reference

plt.scatter(

X_train[:, 0],

X_train[:, 1],

c=y_train,

cmap=plt.cm.colors.ListedColormap([azure, nugget_yellow]),

edgecolors=node_black,

s=50,

alpha=0.5,

label="Clean Data Points",

)

contour_colors = {

0.0: htb_green,

0.10: aquamarine,

0.20: nugget_yellow,

0.30: vivid_purple,

0.40: azure,

0.50: malware_red,

}

contour_linestyles = {

0.0: "solid",

0.10: "dashed",

0.20: "dashed",

0.30: "dashed",

0.40: "dashed",

0.50: "dashed",

}

# Get baseline boundary data

baseline_model_idx = results["percentage"].index(0.0)

baseline_model_retrieved = results["model"][baseline_model_idx]

if baseline_model_retrieved:

Z_baseline = baseline_model_retrieved.predict(mesh_points).reshape(xx.shape)

cs = plt.contour(

xx,

yy,

Z_baseline,

levels=[0.5],

colors=[contour_colors[0.0]],

linestyles=[contour_linestyles[0.0]],

linewidths=[2.5],

)

boundary_indices_to_plot = [0.10, 0.20, 0.30, 0.40, 0.50]

plotted_percentages = [0.0]

# Sort decision_boundaries_data by percentage to ensure consistent plotting order

decision_boundaries_data.sort(key=lambda item: item["percentage"])

for data in decision_boundaries_data:

pp = data["percentage"]

if pp in boundary_indices_to_plot:

if pp in contour_colors and pp in contour_linestyles:

Z = data["Z"]

cs = plt.contour(

xx,

yy,

Z,

levels=[0.5],

colors=[contour_colors[pp]],

linestyles=[contour_linestyles[pp]],

linewidths=[2.5],

)

plotted_percentages.append(pp)

else:

print(f"Warning: Style not defined for {pp * 100}%, skipping contour.")

plt.title(

"Shift in Decision Boundary with Increasing Label Flipping",

fontsize=16,

color=htb_green,

)

plt.xlabel("Feature 1", fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel("Feature 2", fontsize=12)

# Create legend

legend_handles = []

for pp in sorted(plotted_percentages):

if (

pp in contour_colors and pp in contour_linestyles

): # Check again before creating legend entry

legend_handles.append(

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

color=contour_colors[pp],

lw=2.5,

linestyle=contour_linestyles[pp],

label=f"Boundary ({pp * 100:.0f}% Poisoned)",

)

)

# Add legend for data points as well

data_handles = [

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="o",

color="w",

label="Class 0",

markersize=10,

markerfacecolor=azure,

linestyle="None",

),

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="o",

color="w",

label="Class 1",

markersize=10,

markerfacecolor=nugget_yellow,

linestyle="None",

),

]

plt.legend(handles=legend_handles + data_handles, title="Boundaries & Data")

plt.grid(True, color=hacker_grey, linestyle="--", linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.3)

plt.xlim(xx.min(), xx.max())

plt.ylim(yy.min(), yy.max())

plt.show()

Which will generate this plot:

Here we can clearly see the decision boundary becoming increasingly distorted as the model attempted to accommodate the incorrect labels for each fraction of poisoned data.

So far, we have explored Label Flipping. The primary goal there was general performance degradation - making the model less accurate overall. Now let's explore a more focused variant of a data poisoning attack: the Targeted Label Attack.

Unlike the broad impact caused by random label flipping, a Targeted Label Attack has a more specific objective: an adversary aims to cause the trained model to misclassify specific, chosen target instances or, more commonly, instances belonging to a particular target class. Instead of just reducing overall accuracy, the adversary wants to manipulate the model's behavior in a predictable way for certain inputs.

We are going to revisit the same sentiment analysis scenario from the previous attack, but instead of just making the model generally worse at distinguishing positive from negative reviews, we are going to use a targeted approach specifically aiming to make the model misclassify genuinely positive reviews about a product as negative. This requires a slightly more strategic approach to poisoning the data.

Our strategy is to identify training data points belonging to the target class (e.g., positive reviews, Class 1) and then deliberately change their labels to represent a different class (e.g., negative, Class 0). This focused manipulation directly interferes with the model's learning process concerning its understanding and classification of the target class.

We have already established that a Logistic Regression model is trained by minimizing the average binary cross-entropy (or log-loss) function, L:

L(𝐰,b)=−1N∑i=1N[yilog(pi)+(1−yi)log(1−pi)]

Here, yi is the true label (0 or 1), and pi is the model’s predicted probability that instance 𝐱i belongs to Class 1, calculated as pi=σ(𝐰T𝐱i+b), where σ is the sigmoid function, and as we know, the model adjusts its weights 𝐰 and bias b to make the predicted probabilities pi align closely with the true labels yi, thus minimizing L.

Now, consider a targeted attack aiming to make the model misclassify Class 1 instances as Class 0. The adversary selects a subset of training instances (𝐱j,yj) where the true label yj is 1. They then change these labels in the training data to yj′=0.

During training, when the model processes such a poisoned instance 𝐱j, it is expected to calculate a high probability pj (close to 1) because the features of 𝐱j strongly suggest it belongs to Class 1.

With the original label (yj=1), the contribution to the loss for this instance would be −log(pj), which is small if pj is high (close to 1).With the flipped label (yj′=0), the contribution to the loss becomes −log(1−pj). Since pj is high, (1−pj) is low (close to 0), making −log(1−pj) a very large positive value.

This large error signal, specifically generated by instances that look like Class 1 but are labeled as Class 0, significantly impacts the parameter updates during optimization (e.g., by yielding large gradients). The model is forced to adjust 𝐰 and b to reduce this artificially large error. This adjustment inevitably pushes the decision boundary - the threshold defined by 𝐰T𝐱+b=0 where the model is uncertain (p=0.5) - away from its optimal position. In other words, the boundary shifts specifically to incorrectly classify more of the feature region associated with true Class 1 instances as Class 0. This creates the intended bias, making the model prone to misclassifying genuine Class 1 samples.

To execute this strategy, we define a new function that will allow us to specify which class to target and what percentage of only that class's samples should have their labels flipped.

The logic looks like the following:

target_class.poison_percentage applied only to the count of target class samples.from the identified target class indices.First, we define the function signature and perform essential input validation. We check if poison_percentage is within the valid range [0, 1]. We also ensure the target_class and new_class are distinct and that both specified classes actually exist within the provided label array y. Raising errors for invalid inputs prevents unexpected behavior later.

Code: python

def targeted_flip_labels(y, poison_percentage, target_class, new_class, seed=1337):

if not 0 <= poison_percentage <= 1:

raise ValueError("poison_percentage must be between 0 and 1.")

if target_class == new_class:

raise ValueError("target_class and new_class cannot be the same.")

# Ensure target_class and new_class are present in y

unique_labels = np.unique(y)

if target_class not in unique_labels:

raise ValueError(f"target_class ({target_class}) does not exist in y.")

if new_class not in unique_labels:

raise ValueError(f"new_class ({new_class}) does not exist in y.")

Next, we identify the specific samples belonging to the target_class. We use np.where to find all indices in the label array y where the label matches target_class. The number of such samples (n_target_samples) is stored. If no samples of the target_class are found, we print a warning and return the original labels unchanged, as no flipping is possible.

Code: python

# Identify indices belonging to the target class

target_indices = np.where(y == target_class)[0]

n_target_samples = len(target_indices)

if n_target_samples == 0:

print(f"Warning: No samples found for target_class {target_class}. No labels flipped.")

return y.copy(), np.array([], dtype=int)

Based on the number of target samples found (n_target_samples) and the desired poison_percentage, we calculate the absolute number of labels to flip (n_to_flip). This calculation ensures the percentage is only applied relative to the size of the target class subset. If the calculated n_to_flip is zero (e.g., due to a very low percentage or small target class size), we issue a warning and return without making changes.

Code: python

# Calculate the number of labels to flip within the target class

n_to_flip = int(n_target_samples * poison_percentage)

if n_to_flip == 0:

print(f"Warning: Poison percentage ({poison_percentage * 100:.1f}%) is too low "

f"to flip any labels in the target class (size {n_target_samples}).")

return y.copy(), np.array([], dtype=int)

To select which specific samples within the target class will have their labels flipped, we employ a random selection process governed by the provided seed for reproducibility. We initialize a dedicated NumPy random number generator (rng_instance) with this seed. Then, we randomly choose n_to_flip unique indices from the set of target class indices (target_indices).

This selection (indices_within_target_set_to_flip) refers to positions within the target_indices array; we then map these back to the original indices in the full y array to get flipped_indices.

Code: python

# Use a dedicated random number generator instance with the specified seed

rng_instance = np.random.default_rng(seed)

# Randomly select indices from the target_indices subset to flip

# These are indices relative to the target_indices array

indices_within_target_set_to_flip = rng_instance.choice(

n_target_samples, size=n_to_flip, replace=False

)

# Map these back to the original array indices

flipped_indices = target_indices[indices_within_target_set_to_flip]

Now we perform the label flipping. To avoid modifying the input array directly, we create a copy named y_poisoned. Using the flipped_indices obtained above, we access these specific locations in y_poisoned and assign them the value of new_class.

Code: python

# Create a copy to avoid modifying the original array

y_poisoned = y.copy()

# Perform the flip for the selected indices to the new class label

y_poisoned[flipped_indices] = new_class

For clarity and verification, we include print statements summarizing the operation: detailing the classes involved, the number of target samples identified, the number intended to be flipped, and the actual number successfully flipped.

Code: python

print(f"Targeting Class {target_class} for flipping to Class {new_class}.")

print(f"Identified {n_target_samples} samples of Class {target_class}.")

print(f"Attempting to flip {poison_percentage * 100:.1f}% ({n_to_flip} samples) of these.")

print(f"Successfully flipped {len(flipped_indices)} labels.")

Finally, the function returns the y_poisoned array containing the modified labels (with the targeted flips applied) and the flipped_indices array, which identifies precisely which samples were altered.

Code: python

return y_poisoned, flipped_indices

The next step is to generate the poisoned dataset

Code: python

poison_percentage_targeted = 0.40 # Target 40%

target_class_to_flip = 1 # Target Class 1 (Positive)

new_label_for_flipped = 0 # Flip them to Class 0 (Negative)

# Use the function to create the poisoned dataset

y_train_targeted_poisoned, targeted_flipped_indices = targeted_flip_labels(

y_train,

poison_percentage_targeted,

target_class_to_flip,

new_label_for_flipped,

seed=SEED, # Use the global SEED for reproducibility

)

print("\n--- Visualizing Targeted Poisoned Data ---")

# Plot the result of the targeted flip

plot_poisoned_data(

X_train,

y_train, # Pass original y

y_train_targeted_poisoned,

targeted_flipped_indices,

title=f"Training Data: {poison_percentage_targeted * 100:.0f}% of Class {target_class_to_flip} Flipped to {new_label_for_flipped}",

target_class_info=target_class_to_flip,

)

Then train a new LogisticRegression model using this poisoned data. We use the original features X_train but pair them with the corrupted labels y_train_targeted_poisoned.

Code: python

targeted_poisoned_model = LogisticRegression(random_state=SEED)

targeted_poisoned_model.fit(X_train, y_train_targeted_poisoned)

With the new model trained, we can next evaluate its performance. We do this by evaluating the poisoned model on the clean test set to

Code: python

# Predict on the original, clean test set

y_pred_targeted = targeted_poisoned_model.predict(X_test)

# Calculate accuracy on the clean test set

targeted_accuracy = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred_targeted)

print(f"\n--- Evaluating Targeted Poisoned Model ---")

print(f"Accuracy on clean test set: {targeted_accuracy:.4f}")

print(f"Baseline accuracy was: {baseline_accuracy:.4f}")

# Display classification report

print("\nClassification Report on Clean Test Set:")

print(

classification_report(y_test, y_pred_targeted, target_names=["Class 0", "Class 1"])

)

# Plot confusion matrix

cm_targeted = confusion_matrix(y_test, y_pred_targeted)

plt.figure(figsize=(6, 5))

sns.heatmap(

cm_targeted,

annot=True,

fmt="d",

cmap="binary",

xticklabels=["Predicted 0", "Predicted 1"],

yticklabels=["Actual 0", "Actual 1"],

cbar=False,

)

plt.xlabel("Predicted Label", color=white)

plt.ylabel("True Label", color=white)

plt.title("Confusion Matrix (Targeted Poisoned Model)", fontsize=14, color=htb_green)

plt.xticks(color=hacker_grey)

plt.yticks(color=hacker_grey)

plt.show()

Which will output this and the confusion matrix:

Code: python

--- Evaluating Targeted Poisoned Model ---

Accuracy on clean test set: 0.8100

Baseline accuracy was: 0.9933

Classification Report on Clean Test Set:

precision recall f1-score support

Class 0 0.73 1.00 0.84 153

Class 1 1.00 0.61 0.76 147

accuracy 0.81 300

macro avg 0.86 0.81 0.80 300

weighted avg 0.86 0.81 0.80 300

The attack dropped the model's accuracy from the baseline 0.9933 to 0.8100. The classification report shows the specific impact: Class 1 recall fell sharply to 0.61, meaning the poisoned model correctly identified only 61% of true Class 1 instances. Correspondingly, the confusion matrix shows 57 False Negatives (Actual Class 1 predicted as Class 0). This confirms the attack successfully degraded the model's performance specifically for the intended target class.

We can plot the boundary of the targeted_poisoned_model compared to the baseline_model to clearly see how the boundary has shifted with the attack.

Code: python

# Plot the comparison of decision boundaries

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

# Plot Baseline Decision Boundary (Solid Green)

Z_baseline = baseline_model.predict(mesh_points).reshape(xx.shape)

plt.contour(

xx,

yy,

Z_baseline,

levels=[0.5],

colors=[htb_green],

linestyles=["solid"],

linewidths=[2.5],

)

# Plot Targeted Poisoned Decision Boundary (Dashed Red)

Z_targeted = targeted_poisoned_model.predict(mesh_points).reshape(xx.shape)

plt.contour(

xx,

yy,

Z_targeted,

levels=[0.5],

colors=[malware_red],

linestyles=["dashed"],

linewidths=[2.5],

)

plt.title(

"Comparison: Baseline vs. Targeted Poisoned Decision Boundary",

fontsize=16,

color=htb_green,

)

plt.xlabel("Feature 1", fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel("Feature 2", fontsize=12)

# Create legend combining data points and boundaries

handles = [

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

color=htb_green,

lw=2.5,

linestyle="solid",

label=f"Baseline Boundary (Acc: {baseline_accuracy:.3f})",

),

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

color=malware_red,

lw=2.5,

linestyle="dashed",

label=f"Targeted Poisoned Boundary (Acc: {targeted_accuracy:.3f})",

),

]

plt.legend(handles=handles, title="Boundaries & Data Points")

plt.grid(True, color=hacker_grey, linestyle="--", linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.3)

plt.xlim(xx.min(), xx.max())

plt.ylim(yy.min(), yy.max())

plt.show()

Which will generate this image, showing the shift in the boundary:

The plot vividly illustrates the effect of the attack. The targeted poisoned boundary has significantly shifted away from the boundary of the baseline model. The model, forced to accommodate the flipped Class 1 points (now labeled as Class 0), has learned a boundary that is much more likely to classify genuine Class 1 instances as Class 0.

The true test of the attack is how the poisoned model performs on new, previously unseen data. Let's generate a fresh batch of data points using similar distribution parameters (cluster_std=1.50 is a little bigger for a bit of a data spread) as our original dataset but with a different random seed to ensure they are distinct. We will then use our targeted_poisoned_model to classify these points and see how many instances of the target class (Class 1) are misclassified, and display the boundary line.

Code: python

# Define parameters for unseen data generation

n_unseen_samples = 500

unseen_seed = SEED + 1337

# Generate unseen data

X_unseen, y_unseen = make_blobs(

n_samples=n_unseen_samples,

centers=centers,

n_features=2,

cluster_std=1.50,

random_state=unseen_seed,

)

# Predict labels for the unseen data using the targeted poisoned model

y_pred_unseen_poisoned = targeted_poisoned_model.predict(X_unseen)

# Calculate misclassification statistics

true_target_class_indices = np.where(y_unseen == target_class_to_flip)[0]

misclassified_target_mask = (y_unseen == target_class_to_flip) & (

y_pred_unseen_poisoned != target_class_to_flip

)

misclassified_target_indices = np.where(misclassified_target_mask)[0]

n_true_target = len(true_target_class_indices)

n_misclassified_target = len(misclassified_target_indices)

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

# Plot all unseen points, colored by the poisoned model's prediction

plt.scatter(

X_unseen[:, 0],

X_unseen[:, 1],

c=y_pred_unseen_poisoned,

cmap=plt.cm.colors.ListedColormap([azure, nugget_yellow]),

edgecolors=node_black,

s=50,

alpha=0.7,

label="Predicted Label",

)

# Highlight the misclassified target points

if n_misclassified_target > 0:

plt.scatter(

X_unseen[misclassified_target_indices, 0],

X_unseen[misclassified_target_indices, 1],

facecolors="none",

edgecolors=malware_red,

linewidths=1.5,

marker="X",

s=120,

label=f"Misclassified (True Class {target_class_to_flip})",

)

# Calculate and plot decision boundary

Z_targeted_boundary = targeted_poisoned_model.predict(mesh_points).reshape(xx.shape)

plt.contour(

xx,

yy,

Z_targeted_boundary,

levels=[0.5],

colors=[malware_red],

linestyles=["dashed"],

linewidths=[2.5],

)

# Set title

plt.title(

f"Poisoned Model Predictions & Boundary on Unseen Data\n({n_misclassified_target} of {n_true_target} Class {target_class_to_flip} samples misclassified)",

fontsize=16,

color=htb_green,

)

plt.xlabel("Feature 1", fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel("Feature 2", fontsize=12)

# Create legend

handles = [

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="o",

color="w",

label=f"Predicted as Class 0 (Azure)",

markersize=10,

markerfacecolor=azure,

linestyle="None",

),

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="o",

color="w",

label=f"Predicted as Class 1 (Yellow)",

markersize=10,

markerfacecolor=nugget_yellow,

linestyle="None",

),

*(

[

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

marker="X",

color="w",

label=f"Misclassified (True Class {target_class_to_flip})",

markersize=12,

markeredgecolor=malware_red,

markerfacecolor="none",

linestyle="None",

)

]

if n_misclassified_target > 0

else []

),

plt.Line2D(

[0],

[0],

color=malware_red,

lw=2.5,

linestyle="dashed",

label="Decision Boundary (Targeted Model)",

),

]

plt.legend(handles=handles, title="Predictions, Errors & Boundary")

plt.grid(True, color=hacker_grey, linestyle="--", linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.3)

# Set plot limits

plt.xlim(xx.min(), xx.max())

plt.ylim(yy.min(), yy.max())

# Apply theme to background

fig = plt.gcf()

fig.set_facecolor(node_black)

ax = plt.gca()

ax.set_facecolor(node_black)

plt.show()

This visualization shows the targeted_poisoned_model's predictions and its decision boundary applied to the unseen data.

The points marked with a red 'X' represent true Class 1 instances that the poisoned model incorrectly predicts as Class 0. These misclassifications primarily occur within the actual Class 1 cluster but fall on the Class 0 side of the shifted decision boundary (dashed red line).

This clearly demonstrates how the boundary shift induced by the targeted attack successfully causes the intended misclassifications on new, unseen data.

So far, we have explored data poisoning attacks like Label Flipping and Targeted Label Flipping. Both of these methods directly manipulated the ground truth labels associated with training data instances. We now explore another category of data poisoning attacks: the Clean Label Attack.

A defining characteristic of Clean Label Attacks compared to the label attacks, is that they do not alter the ground truth labels of the training data. Instead, an adversary carefully modifies the features of one or more training instances. These modifications are crafted such that the original assigned label remains plausible (or technically correct) for the modified features. The goal is typically highly targeted: to cause the model trained on this poisoned data to misclassify specific, pre-determined target instances during inference. This happens even though the poisoned training data itself might appear relatively normal, with labels that seem consistent with the (perturbed) features.

Let's consider a manufacturing quality control scenario. Imagine a system using measurements like component length and component weight (the features) to automatically classify manufactured parts into three categories: Major Defect (Class 0), Acceptable (Class 1), or Minor Defect (Class 2). Suppose an adversary wants a specific batch of Acceptable parts (target instance, true label 1) to be rejected by being classified as having a Major Defect.

Using a Clean Label Attack, an adversary could take several training data examples originally labeled as Major Defect. They would then subtly alter the recorded length and weight features of these specific Major Defect examples. The perturbations would be designed to shift the feature representation of these parts closer to the region typically occupied by Acceptable parts in the feature space. However, these perturbed samples retain their original Major Defect designation within the poisoned training dataset.

When the quality control model is retrained on this manipulated data, it encounters data points labeled Major Defect that are situated closer to, or even within, the feature space region associated with Acceptable parts. To correctly classify these perturbed points according to their given Major Defect label while minimizing training error, the model is forced to adjust its learned decision boundary between Class 0 and Class 1. This induced adjustment could shift the boundary sufficiently to encompass the chosen target instance (the truly Acceptable batch), causing it to be misclassified as Major Defect. The attack succeeds without ever directly changing any labels in the training data, only modifying feature values subtly.

To demonstrate this, we will create a synthetic dataset consisting of three classes, suitable for our quality control scenario. We will generate the data using the same make_blobs function.

Each instance 𝐱i=(xi1,xi2) will represent a part with two features (e.g., conceptual length and weight), and the corresponding label yi will belong to one of three classes: {0,1,2} (representing Major Defect, Acceptable, Minor Defect). We will also apply feature scaling to normalize the dataset.

Code: python

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import make_blobs

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, classification_report, confusion_matrix

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.neighbors import NearestNeighbors

from sklearn.multiclass import OneVsRestClassifier

import seaborn as sns

# Color palette

htb_green = "#9fef00"

node_black = "#141d2b"

hacker_grey = "#a4b1cd"

white = "#ffffff"

azure = "#0086ff" # Class 0

nugget_yellow = "#ffaf00" # Class 1

malware_red = "#ff3e3e" # Class 2

vivid_purple = "#9f00ff" # Highlight/Accent

aquamarine = "#2ee7b6" # Highlight/Accent

# Configure plot styles

plt.style.use("seaborn-v0_8-darkgrid")

plt.rcParams.update(

{

"figure.facecolor": node_black,

"axes.facecolor": node_black,

"axes.edgecolor": hacker_grey,

"axes.labelcolor": white,

"text.color": white,

"xtick.color": hacker_grey,

"ytick.color": hacker_grey,

"grid.color": hacker_grey,

"grid.alpha": 0.1,

"legend.facecolor": node_black,

"legend.edgecolor": hacker_grey,

"legend.frameon": True,

"legend.framealpha": 0.8, # Slightly transparent legend background

"legend.labelcolor": white,

"figure.figsize": (12, 7), # Default figure size

}

)

# Seed for reproducibility - MUST BE 1337

SEED = 1337

np.random.seed(SEED)

print("Setup complete. Libraries imported and styles configured.")

# Generate 3-class synthetic data

n_samples = 1500

centers_3class = [(0, 6), (4, 3), (8, 6)] # Centers for three blobs

X_3c, y_3c = make_blobs(

n_samples=n_samples,

centers=centers_3class,

n_features=2,

cluster_std=1.15, # Standard deviation of clusters

random_state=SEED,

)

# Standardize features

scaler = StandardScaler()

X_3c_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X_3c)

# Split data into training and testing sets, stratifying by class

X_train_3c, X_test_3c, y_train_3c, y_test_3c = train_test_split(

X_3c_scaled, y_3c, test_size=0.3, random_state=SEED, stratify=y_3c

)

print(f"\nGenerated {n_samples} samples with 3 classes.")

print(f"Training set size: {X_train_3c.shape[0]} samples.")

print(f"Testing set size: {X_test_3c.shape[0]} samples.")

print(f"Classes: {np.unique(y_3c)}")

print(f"Feature shape: {X_train_3c.shape}")

Running the code cell above generates our three-class dataset, standardizes the features, and splits it into training and testing sets. The output confirms the size and class distribution.

Code: python

Setup complete. Libraries imported and styles configured.

Generated 1500 samples with 3 classes.

Training set size: 1050 samples.

Testing set size: 450 samples.

Classes: [0 1 2]

Feature shape: (1050, 2)

Visualizing the clean training data is the best way to understand the initial separation between the classes before any attack occurs. We will adapt our plotting function to handle multiple classes and allow for highlighting specific points, which will be useful later for identifying the target and perturbed points.

Code: python

def plot_data_multi(

X,

y,

title="Multi-Class Dataset Visualization",

highlight_indices=None,

highlight_markers=None,

highlight_colors=None,

highlight_labels=None,

):

"""

Plots a 2D multi-class dataset with class-specific colors and optional highlighting.

Automatically ensures points marked with 'P' are plotted above all others.

Args:

X (np.ndarray): Feature data (n_samples, 2).

y (np.ndarray): Labels (n_samples,).

title (str): The title for the plot.

highlight_indices (list | np.ndarray, optional): Indices of points in X to highlight. Defaults to None.

highlight_markers (list, optional): Markers for highlighted points (recycled if shorter).

Points with marker 'P' will be plotted on top. Defaults to ['o'].

highlight_colors (list, optional): Edge colors for highlighted points (recycled). Defaults to [vivid_purple].

highlight_labels (list, optional): Labels for highlighted points legend (recycled). Defaults to [''].

"""

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 7))

# Define colors based on the global palette for classes 0, 1, 2 (or more if needed)

class_colors = [

azure,

nugget_yellow,

malware_red,

] # Extend if you have more than 3 classes

unique_classes = np.unique(y)

max_class_idx = np.max(unique_classes) if len(unique_classes) > 0 else -1

if max_class_idx >= len(class_colors):

print(

f"{malware_red}Warning:{white} More classes ({max_class_idx + 1}) than defined colors ({len(class_colors)}). Using fallback color."

)

class_colors.extend([hacker_grey] * (max_class_idx + 1 - len(class_colors)))

cmap_multi = plt.cm.colors.ListedColormap(class_colors)

# Plot all non-highlighted points first

plt.scatter(

X[:, 0],

X[:, 1],

c=y,

cmap=cmap_multi,

edgecolors=node_black,

s=50,

alpha=0.7,

zorder=1, # Base layer

)

# Plot highlighted points on top if specified

highlight_handles = []

if highlight_indices is not None and len(highlight_indices) > 0:

num_highlights = len(highlight_indices)

# Provide defaults if None

_highlight_markers = (

highlight_markers

if highlight_markers is not None

else ["o"] * num_highlights

)

_highlight_colors = (

highlight_colors

if highlight_colors is not None

else [vivid_purple] * num_highlights

)

_highlight_labels = (

highlight_labels if highlight_labels is not None else [""] * num_highlights

)

for i, idx in enumerate(highlight_indices):

if not (0 <= idx < X.shape[0]):

print(

f"{malware_red}Warning:{white} Invalid highlight index {idx} skipped."

)

continue

# Determine marker, edge color, and label for this point